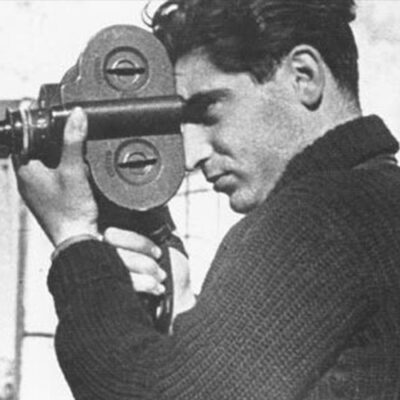

Speaker The man whom we know is Robert Capa was actually born Andrew Friedman to middle class Jewish parents in Budapest. His parents had a fashionable dressmaking salon and Julia and Ethel Friedman were as different as any two people could be. Julia was a very strong woman, very ambitious, very capable, and very much the the motivating force in the family where it was a kind of easygoing man, rather introverted, whose greatest pleasure was playing cards with a couple of friends at a local cafe.

Speaker Do you think that this drove Julia little crazy?

Speaker I mean, she kind of got the brunt of work.

Speaker Julia ran the salon and she worked with the customers where her husband spent more time in the back making the clothes and there was a running battle trying to keep him on the job because he was a master at sneaking out to go have a good time.

Speaker Was great, that was great. And what what do you think the freedom and recruitment we took from each of his parents?

Speaker I would say that Andrea Friedman, Robert Capa took from his mother the the strength to do what needed to be done, to work very hard, to be very focused and ambitious from his father. He took a love of life, a resourcefulness to manage very comfortably in any situation in which he found himself. And very important. He got a love of gambling and a real gamblers personality from his father. Once again, his personality, Capote was willing to take extraordinary risks, not foolish risks. He he was not a reckless man. He certainly had no deathwish as a war photographer. He was a very shrewd judge of military situations, but he was a very brave man and he had a sense of luck. He felt lucky and a gambler’s luck. He used to say that as long as he kept losing at cards, then he was OK in the field.

Speaker It’s so funny, I mean, it’s as if he’s paying off one debt to keep I mean, to keep a balance. Yeah, yeah, that’s interesting. And and just while we’re on that subject, you can talk about what kind of a poker player he was, which is kind of touched on.

Speaker Etc. cafA love to play poker, but for him it was very much a social activity. He occasionally would win money. There are stories of getting Magnum out of some cash flow crises by a lucky poker game, but on the whole he tended to lose. And that was a bit of a good luck charm for him to lose because that seemed to guarantee that in the serious side of his life, working as a war photographer, that his luck would hold.

Speaker I just want to say that you’re doing fantastically well, thank you. You’re saying is the perfect little jewel. Thank you. Thank you. Absolutely.

Speaker Great. Good choice. Skip the chance. OK. All right. Next question I had on here about being Hungarian.

Speaker What what does it mean to be here and how did that shape everything on campus life?

Speaker Although it’s always dangerous to generalize about national traits, I would say that Hungarians in general seem to be very resourceful people, perhaps because of the very awkward position that they have suffered through in history. And there is a touch of Middle Eastern horse trading because of the long Turkish occupation of Hungary. There is a very strong gypsy component in the national character, and the Hungarian language has been a crucial factor because it’s unrelated to any other major European language. And that has meant that when a Hungarian leaves his or her native land, that some means of expression must be found. And that has tended overwhelmingly to be either music or the visual arts, particularly photography.

Speaker Yeah, I mean, you mentioned while we’re on that subject, all or some of the incredible Liberians who made their names in visual arts.

Speaker Just in the field of photography, some of the very greatest photographers of the 20th century have been Hungarian in origin Andriukaitis, Brassai, LaSalle, Marjolein, age to name just three, and and then, of course, the two Kalpoe brothers, Robert Capa and Cornell Capa.

Speaker This is a question more for you you’ve mentioned.

Speaker I’m talking about when you do the research, the way that people responded when you asked them about chemicals. So interesting.

Speaker I must have interviewed easily 100 people who had known Robert Capa, and I think almost every single one of them spoke of two qualities in particular. First and foremost, Capa’s generosity. He was always ready to help out with money, even to give away a camera when necessary. And the other particularly distinctive trait was his sense of humor, which was also a form of generosity. Perhaps he loved to cheer people up. He loved to make people laugh. And he was very good at it.

Speaker That’s great. And you also mentioned something I’d love to get the most amazing people, many of whom actually don’t have all that well. What I mean is there.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. Some of these people whom I interviewed after telling me the cappa was one of the best friends they ever had, I would begin to ask about the time they’d spent together, would turn out. They’d maybe spent a couple hours here and there together total. But Kappus impact was so strong that time was irrelevant.

Speaker And you also said something about yourself and getting to know Robert Kaplan to I don’t think that’s so relevant.

Speaker Let’s focus on you. Very nice, though. Yeah, but that’s all right now.

Speaker Let’s talk a little bit about how the economics of the twenty nine affect and how that wealth is better.

Speaker Well, let’s talk first about how Colpeper got to Berlin.

Speaker Well, 12 days before he goes to Berlin.

Speaker Yeah, but it didn’t really affect them. Oh, well, I see. You mean the video.

Speaker That’s. I’d like to skip that, I think.

Speaker All right, so all right, so let’s talk about let’s talk about Cappa and his teenage years and his thinking of a profession.

Speaker Great. OK. And what I’d love to have you include in that, too, is what you know, he was very much politically involved.

Speaker We all know that will be. Yeah, yeah, yeah. OK, great.

Speaker Actually, I should begin with a little bit of a little bit of Hungarian background. It’s important to understand that when the Austrian empire broke up at the end of World War One, there was briefly a Hungarian communist revolution, communist republic, and that brought on a terrible reaction from the far right. A Romanian admiral Horthy came in, the head of the army, became the head of state of Hungary until the Nazis came in. And he was essentially a fascist in spirit. He was anti-Semitic, had a very repressive government. And this affected Robert Capa and his entire generation very strongly. Kalpa knew that he would probably not be admitted to a Hungarian university which had a quota on Jewish students. He felt early that he wanted to be a journalist to report on what he saw about the world, what needed to be changed, particularly. And he didn’t aspire to be a photographer. He wanted to be a reporter to combine his two great loves of literature and politics.

Speaker OK, um.

Speaker OK. Well, I thought Coshocton demonstration. Yeah, I’m going to get Korshak right now. OK.

Speaker So arithmetics.

Speaker And this is OK, so in the fall of 1929, when Kalpa was 16 years old, he met a very charismatic and important Hungarian named Lyall’s Korshak, who was the leader of the avant garde in literature and the visual arts. Korshak was an extraordinary man who had been to Paris and who had participated in the communist government of 1919 and led the Hungarian laughs. He was the conscience, shall we say, of the Hungarian left in it. Now, this is too complicated. Let me start over. It’s much, much too much. What do you need here?

Speaker I’m just the beginnings of his political commitment. OK.

Speaker Is his determination to fight fascism with continued?

Speaker Young how that began and also is interested in the avant garde art scene in.

Speaker And because of his influence, but wouldn’t get to deeply into no, OK, let me just think I wanted.

Speaker As a high school student, Kappus, two passions were politics and literature. He lived in a nation that had a proto fascist government, very anti-Semitic, and so it was natural for him to gravitate towards leftist politics, to bring about change. His aspiration was to become a reporter, not a photographer, but a print reporter to combine his two great loves. And he also was very precociously active in politics. It was a time of street demonstrations in Budapest. Cupper participated as students have always participated in such things. He was noticed by the secret police and he was wounded at one point. And one of these demonstrations and all of this led to his being singled out by the police as a troublemaker so that when Cowpat had the idea that he might want to join the Communist Party and contacted a recruiter, spent an evening walking through the streets of Budapest discussing politics and what it meant to be a communist, what it meant for a bourgeois young man to be a communist. He was watched. He was subsequently arrested. And the story of his release is so Hungarian, the wife of the chief of police happened to be a customer of the Friedmans dressmaking salon. A word to her was transmitted to her husband, who effected the release of the young man on the condition that as soon as he finished up his senior year in high school in a few weeks, he would leave the country.

Speaker So that was that was that OK? I hope you weren’t sitting in for the traffic report, so OK.

Speaker The story of Kappus release is wonderfully Hungaria, it happened that the wife of the chief of police was a customer of the Friedmans dressmaking salon, a word to her was transmitted to her husband, who arranged for the immediate release of the young man from jail where he’d been held overnight, and but on the condition that as soon as he finished up his high school work in a few weeks, he would have to leave the country. So. Andrew Friedman, not yet at his 18th birthday, became a political exile.

Speaker That’s great, great. OK, and why Berlin?

Speaker Berlin was a natural choice as the place for Andre Friedman to go for a number of reasons. One German was his second language, as it was for virtually all educated Hungarians. Secondly, Berlin was the center of the new journalism.

Speaker German magazines led the world in their very avant garde design and the simply.

Speaker When Andre Friedman left Budapest, Mr Rivkin, OK.

Speaker When Andre Friedman had to leave Hungary, Berlin was the natural place to go first German was his second language, as it was, of almost all educated Hungarians. Secondly, Berlin had become the world capital of journalism. There was a great school, The Hawkshaw for Politique, which had an outstanding journalism program, and it was to study at that school that Kapur traveled partly on foot to partly hitchhiking, partly by train to Berlin in the summer of 1931. Excellent.

Speaker Now, I remember something in your book about the day left.

Speaker Julia was so distraught, you know, that I don’t remember. All right. Let’s move on to Berlin.

Speaker OK, one thing that’s going there for one second, I was going to do a recreation of this being in jail, very abstract. So would it be good if you could to what happened to him when he was arrested?

Speaker She was seriously beaten up.

Speaker Yeah, I could maybe do that with narration. I think I think maybe I’d rather. All right, move on. Yeah, OK.

Speaker And, you know, interesting. And what was his life like there? Pretty difficult. Yeah.

Speaker When Andre arrived in Berlin, he had a little bit of money from his family, but very little, he had to live in pretty sleazy surroundings, he had to economize. Now, this is just a system that didn’t work at all. Let me. Let me.

Speaker I like the sleazy surroundings, you know, and they were pretty sleazy, um.

Speaker The Freedman family could barely afford to pay for Andrew’s tuition, so for living, Andre had to struggle. He lived in a sleazy boarding house. He ate whatever he could catch from friends. Really, it was a very tough life. And that life became a great deal more difficult in that winter when the worldwide economic depression finally had a devastating impact on hungry. And Andrew’s parents could no longer afford to send him any money at all. At that point, he had to get a job. He remained in school part time, but he used his Hungarian connections to ask around what might be available. He was directed towards a photo agency called Davut for Deutche Photo Dienst, the German photo service, which was the leading me that was that cut. Some of that was useful.

Speaker But let me start over, start over, back a little bit, OK? Something OK?

Speaker So we had to get a job. OK?

Speaker Andre used his Hungarian connections as there was a Hungarian network in all of the cities that we don’t need that are refocussed. What do you need here? We would devote half life, tough life. You kind of. Yeah.

Speaker And then he he started at the bottom in this photo.

Speaker OK, whole he wasn’t to care how we got there. I mean, Hungarian connections. Do you care about that. You want that.

Speaker OK. Yeah but but but the main thing is how hard it was, you know, that you can call it was it was an errand boy who was kicked out of his rent those.

Speaker Okay. Uh, you know, some of that. Let me let me see how I can do this in a nutshell, OK?

Speaker When Andre needed a job, he used his Hungarian connections and landed a job as an errand boy in a wonderful photo agency, the outstanding photo agency, which represented some of the great photographers like Felix, Manh and Zombo. But it was a very tough life, carrying coal to heat the agency’s office, running out to get lunch. But Andrew’s talent was so obvious and so irrepressible that he rose very quickly. He soon was working as a darkroom assistant and then began to do some minor assignments. Swimming meets that sort of thing on the side. But even in those assignments, his talent was so clear that Simon Goodman, the director of the agency, realized that this was a young man with tremendous potential. And in November 1932, an extraordinary opportunity arose. Trotzky, who had been in exile from the Soviet Union, was to speak to a group of Danish university students in Copenhagen. Simon Goodman, knowing that Andre Friedman’s sympathies were basically Trotskyite, decided to give the young man his first huge break. Andre made a great success of this first assignment. His photographs of Trotsky speaking are very powerful. They really convey the charisma and passion of this ardent revolutionary. The photographs were published to great success, not only in Germany, but elsewhere.

Speaker That’s great. And it seems to me that.

Speaker That these photographs show his philosophy that was expressed later about getting close and that wasn’t he the only one who really actually got close to 12?

Speaker I’d like to save that. All right. For later.

Speaker All right. And they were back. Yeah, but those pictures now even better fit into this story.

Speaker Good to mention. Yes, right. Right there. There has to get past the.

Speaker So somebody is turning pages or something.

Speaker But.

Speaker On the same floor as the Friedemann dressmaking salon, there was a large apartment, A.

Speaker OK, operated by no occupied on the same floor as the Friedemann Dressmaking Salon.

Speaker There was a large apartment occupied by a family of the besheer family, and Ava Beshir was slightly older than Andre Friedemann, but they were good friends. She was a serious young photographer studying with Joseph Pache, one of the great commercial photographers of Budapest and ever had a strong political conscience. She went out into some of the poorer neighborhoods of Budapest and photographed and took her young friend Andre along as a companion. This was absolutely crucial in planting the seed. Andre didn’t take up photography at that point, but when he was working a default and Eva Beshir was in Berlin, Andre then went back to her and used that. It’s that. It’s almost almost. Yeah. OK, let me let me just see how much of that how much is OK. So was the first part OK. Do I need to do that all over or.

Speaker That was great. And the only thing where he said it sounded like she was already involved.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. In the apartment. OK, let me guess.

Speaker OK, well yeah she was ok. So.

Speaker On the.

Speaker On the same floor as the Friedemann dressmaking salon, an apartment there was a large apartment occupied by the Bethania family, Eva Besner, who was just two years older than Andre, was beginning to study photography with years of the great commercial photographer of the time. And Eva, who had a strong political conscience, went out into some of the poorest neighborhoods of Budapest to photograph and took her young friend Andre along. It was then it’s safe to say that the seat of the power of photography to bring about social change was planted in Andre.

Speaker That was great, and you might just say, I don’t know whether I even at this point was influenced by the photographs and, you know, we don’t really know.

Speaker And in fact, I say that in my book, but someone I respect greatly has questioned in private conversation whether Hynde’s pictures, what actually happened or rather pictures would actually have been published. I read that somewhere because he was very. Yeah. See, I’ve never had an opportunity to look through Molcho, and it’s just that’s I don’t want that’s something I need. To do so, let’s let’s just say social social photography, maybe if you want to finds a run of mocha, you can show some Lewis Hine and Jacob Rees photographs, but I’d rather skip that right now. OK, so. So then. OK, and I think maybe that’s enough for Ava. Let her talk about it from there. OK. OK, just to introduce her. That’s OK. So we left Andre having had his his success.

Speaker OK.

Speaker And OK, so OK, I think then I’d like to just. Well, I think pretty.

Speaker Um, well, what I was going to say, you might say something kind of quiet, but that this became the way to tell stories, I think he sort of said it, but that really maybe I think that’s premature.

Speaker OK, I think it’s true, but I think it comes in maybe later. I’m not sure at this point, really. He was he was just starting, I think, without. Thinking this through too much, so I think what I’d like to say is this. OK, before Andre could capitalize on his first great success, Hitler rose to power and Andre was already being harassed in the streets of Berlin, and so he felt it was time to leave the city. And after a summer home in Budapest, he made his way in the fall of 1933 to Paris. Did I did I swallow that last syllable too much?

Speaker An OK spelling out not not in great detail, but why he was dressed.

Speaker I mean, he was Jewish, I mean, but for all. OK, ok. OK. I mean.

Speaker I don’t I don’t know, I mean, was he obviously Jewish? He looked more like a gypsy than he wasn’t. I mean, they somehow knew they just so it just seems. Well, I mean, he was a foreigner, he was he certainly he was a very non and maybe I’ll just say he was certainly he was arrested by the attacks.

Speaker Well, I don’t even say he was aroused by by. There were so many. There’s the as you say and, you know, it was it was the Nazis.

Speaker Well, since then, I guess the rise, rising evil that was.

Speaker OK, throughout Andre’s time in Berlin, the Nazi presence was very real. There were street battles, Andre, as a very non Arion looking young man, was a target. And he received a certain amount of harassment which increased dramatically in early 1933 when Hitler came to power.

Speaker So before Andrew was able to capitalize on his first great success with Trotsky, he felt that it was imperative for him to leave Berlin, that his life was really in danger. Now, he made his way first to Vienna, then got permission to return home to Budapest for the summer. And then in the fall of that year of 1933, he finally made his way to Paris.

Speaker And why Paris?

Speaker Paris had become the Mecca for the avant garde for expatriates from all over central Eastern Europe. It was a city of opportunity, a city of freedom, though there was certainly a good deal of xenophobia to which Andre was subject. But there were many Hungarians, many connections, many opportunities.

Speaker And what were some of the things that he photographed in his first year there?

Speaker Some of the things going on that he took pictures of.

Speaker The mid 30s were a time of tremendous political unrest in France, as in all of Europe, the battles of fascists and anti fascists were being fought in microcosm in Paris. And this is what Andre first photographed, his first real introduction to war photography, we might say, riots in the Plaza de la Concorde and the battles in which he felt a truly partisan involvement. He by this time was fully formed as a man of the left with Trotskyites sympathies. He was never a communist, never a Stalinist, perhaps we might say a humanistic socialist.

Speaker And let’s see know maybe you should say a little bit about the phone call to their name, that’s OK.

Speaker Hearing distracted by I’m hearing was that.

Speaker Be aware, guys, that. OK, so the popular.

Speaker By 1935. The threat of fascism of Nazism specifically was so great that awareness began that the factionalism of the left was clearing the way for a Nazi victory. Therefore, many parties of the left from the directed by the Communists.

Speaker That was good in the beginning. And then I got. So it’s really I guess I need to say that this was it was pretty much Stalin’s idea.

Speaker Problem.

Speaker Second, OK. Thank you, sir. Thank you.

Speaker It’s no big difference.

Speaker Yes, you’re going oh, yes, I’m here and this is what you know, they’re both really nice.

Speaker Depends what he says, yeah, but is general like this?

Speaker First of all, a passionate. OK, so OK.

Speaker By 1935, Germany had become so powerful and so threatening that the various French liberal and leftist parties realized their only hope was to put their factional differences aside and form a coalition which they called the Popular Front, the Front Populaire. That front was elected to power in 1936 to great optimism. A minor social revolution was put into work and change was great, but not quite fast enough to meet the expectations of many of the workers. A massive wave of Syrian strikes swept across France, and they provided Robert Capa with some of his first opportunities to do stories that would be bought eagerly by the French press.

Speaker Great, and I want to speak a little bit about those images. What was he looking at?

Speaker What was he trying to convey and thinking about those images of the strikes?

Speaker In Capa’s photographs of the strikes, his characteristic style is very obvious right from the beginning that his interest was in people. How did people respond to difficult or indeed horrendous situations? He carried that interest throughout his work in peacetime at the battlefront. His interest was people. How do people deal with adversity? How does the human spirit triumph over the most horrible conditions with which it can be confronted?

Speaker That was great. That was great and maybe just something about. Obviously, these people, workers were comfortable with them, they allowed him a certain intimacy, I guess that’s what I’m thinking.

Speaker OK, sure, sure.

Speaker We also see in the pictures of the strikes that start over again. We also see in these pictures of the strikes that right from the beginning, Capa’s ability to make people comfortable. Wherever he was in any country, in any situation, had a wonderful influence on his photographs that didn’t go wrong, was almost there sorry. In Cavas, photographs of the strikes, we can see how right from the beginning, his love of people and his ability to communicate that love put people at ease. He was accepted wherever he went, anywhere in the world, in any kind of situation. People felt unselfconscious around him. They trusted him and revealed themselves to him.

Speaker That was great. OK, the meeting with him and we’ll get it back. OK.

Speaker Paris, in the mid 30s, was a wonderful melting pot with expatriates, refugees from fascism having come from all over Europe. Very unlikely people became close friends. In this case, Robert Capa, the young Hungarian political exile, befriended a Polish intellectual exile named David Shiman. Scientists work chhim, and they both became close friends with Frenchmen of the upper middle class of a rather aristocratic bearing on recutting.

Speaker I was so sorry, I suddenly thought I had his name wrong, tangled up in that a photograph or something, so, OK, no, I’ll just start with the lat with that last sentence.

Speaker Also, am I calling or am I still calling, Cowpat? Andre or Kalpa, because you want me to tell the story of the name change, so I should really do this as Andre. Yes, Andre. Well, but here I’ll just go. Right. He will have been wow. He will look at Andre and Kalpa. This is going to be a little bit. I don’t really have. OK, are you OK. OK. How much of that do you want me to do over to start from the beginning or I remember exactly I was fine up until where? Unlikely. So let me let me just leave that if I can. So OK, so. OK, and these two young men befriended a Frenchman of the upper middle class, quite aristocratic bearing named Henry Cartier-Bresson, the three of them were so close, people called them the Three Musketeers. They worked together, the three of them using small 35 millimeter cameras, exploring the possibilities of this new photographic tool to get close to the subjects to achieve an intimacy that was pioneered by Andrew Curtis, who really was the artistic father of all three of them.

Speaker That it’s great. How did your spouse develop, I guess this was early in all their careers where they seem OK, learn their subject similar, different.

Speaker There are certain fundamental similarities among the work of these no, sorry. So there are certain fundamental similarities among the photographs of these three men, what would eventually become the Magnum style black and white photo journalist, humanistic, close and very intelligent observation of situations. But the individual styles were highly distinctive. Cartier-Bresson like to be at the periphery. He was very much the invisible observer of events. He loved the geometry of situations. Nothing could have been further from the way Calpol worked. Capa had no reservations about making his presence known, even speaking to his subjects sometimes before photographing them. He was anything but invisible. He was very engaged. Where Cartier-Bresson was more aloof, Chhim was somewhere in the middle, by temperament, rather shy, but very warm, very gentle, tender man, his photographs beautifully reflect those qualities. That was fabulous.

Speaker That was fabulous. All right, let’s get to Gerta Kingara, her influence on him.

Speaker OK, and the main thing. Yeah, yeah, OK.

Speaker I don’t want to go much into how they met no Ruth SIRF, none of that is too complicated. Just met.

Speaker I mean, people were meeting you when he was taking pick. I mean. Well I think I’d just like to say that he he met a young German.

Speaker And it was the fall of nineteen thirty four, wasn’t it?

Speaker I believe so.

Speaker OK, let’s hope so. Yeah I think so. Later. OK. OK. Thirty four, thank you.

Speaker We have got to be careful.

Speaker In the fall of 1934, after a year in Paris, Andre met a very spirited German woman about two years older than he was named Gerda Paul, realist’s Yugoslavian ancestry, but had lived in Germany, fled the Nazis as he had. They gradually fell in love and Garita transformed her French. She was a very strong person, much like Julia in certain ways, had a very good business sense, knew how important presentation was, very ambitious. And she made sure that this young man who had developed a reputation for being rather irresponsible, for accepting an assignment and then disappearing perhaps for months, he would come back usually with the pictures, but he was not as dependable as the photojournalists should be to change that. She made him get a haircut, get better clothes, deliver his assignments on time, and she would go around and sell the pictures to editors. Person of great charm. She was very persuasive, but not quite persuasive enough. She did have trouble selling the photographs because there was a lot of competition. So she and André decided that it was time for a new strategy and they decided they would invent an American photographer named Robert Capa. Very successful, uh, so famous that nobody could ever really get close to him. He was always away on assignment or some glamorous resort on vacation. And yet his photographs mysteriously made their way to Paris with some dependable regularity. Garita would go around to the editors and tell them that she would do them the favor of giving them the opportunity of buying photographs by this great photographer. Eventually, the ruse was discovered that Andre Friedman was making the photographs the Garita was selling as Robert Kalfus. And what they decided at that point was that since the photographs were so good and they were getting published, that Andre Friedman might just as well become Robert Capa.

Speaker And why, Robert Temple, why that?

Speaker The genesis of the name has much to do with Andre and Gardas love of the cinema. Andre was having so much trouble selling his photographs in 1935 that he actually said in one of his letters to his mother that he felt his work in photography was hopeless, that his only chance of success was to get into the movies. And Andre and Carol used to go to the movies. The name Kalpa seems to be a play on the name of Frank Capra, who had just won an Academy Award. The Robert probably came from Robert Taylor, and Gerda at the same time decided that she needed a change of name. Her release was a very awkward name, and Andre and Gerda had several Japanese friends, one of whom was a sculptor named Taro Okamoto. And Garita decided that the name Karradah Taro sounded enticingly like the name Greta Garbo. And so from from then on, Andrew Friedman and Garappolo realist’s became Robert Capa and Gerda Taro.

Speaker It was fantastic.

Speaker It’s really beautifully done.

Speaker Wow, OK, let’s see where we go. We should go to Julia. Julia did come to power. Oh, let’s skip that.

Speaker OK, um, then, shall we? Maybe we should just get to Spain. I think so. I think so. OK, so, um.

Speaker Well with just to just to preface. I’ll just say that.

Speaker That the first stories I see, um, no, uh, yeah, let’s just get to Spain against another I want to read.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. Oh absolutely. And so we need to keep that going. OK, so.

Speaker All you want to do, Verden, oh, you want to you want to lead from Verden into Spain. Thank you. So let let’s do that.

Speaker OK.

Speaker Once Andre became Robert Capa, opportunities proliferated, one of his most important early assignments was in July nineteen thirty six to cover an international reunion to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Battle of Verdun, one of the longest and bloodiest battles of World War One. French, British, American, Germans, united mostly pacifists in the hope of staving off the war that was becoming increasingly inevitable and this great gathering at Verdun of copper photographed in a very powerful way. His story had great impact. Many of the former combatants brought their sons that the coming generation would learn the lessons of the past. And Capa returned to Paris in time to celebrate Bastille Day nineteen thirty six, but within a week of the ceremony at Verdun. What really was the first great chapter of World War Two erupted in Spain with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Speaker That was great, especially the last part, I think maybe the first part too much was too much, but what I was looking for is the clarity of had been they were celebrating what I understand, 20 years of peace or a ha ha ha ha.

Speaker And then the irony of I think you said yeah, yeah. OK, OK, let me focus on that then. OK, I’ll do that whole thing is very it was a little long anyway, so it was a long and.

Speaker OK. It’s a celebration. They had peace for so long.

Speaker One of the first important assignments that Andre got after becoming Robert Capa was to cover the 20th anniversary of the Battle of Verdun, the longest and bloodiest Battle of World War One. The commemoration was to mark 20 years of peace in Europe and to express that passionate hope that peace would continue. Alas, within one week of that ceremony, the first chapter of World War Two erupted in Spain, the Spanish Civil War.

Speaker Great, OK, great, OK, and OK, so then we need to get. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker Kapa had begun teaching Curda how to use a camera, and so it was natural that when the opportunity arose to go to Spain to cover the war, the two of them would go together. They went first to Barcelona, which was in the throes of an anti-Bush war, social revolution. They went on to cover the fighting in Uruzgan and eventually made their way south to the front near Cordoba.

Speaker So, yeah, did you.

Speaker Is that OK or do I have to do that over to do that again? OK. OK.

Speaker Eventually, he eventually no one can kick.

Speaker Eventually, they made their way south to Cordoba, and it was on the Cordoba Front, that cappa, who was a few weeks short of his 21st birthday, made what has been ever since, almost universally hailed as one of the greatest war photographs ever made.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, yeah. OK, let me let me do the whole thing.

Speaker Eventually, they made their way south to Andalusia and it was on the front door just OK. And so eventually they made their way south to Andalusia and it was on the front just north of Cordoba. That Cappa, who was a few weeks short of his twenty third birthday, made what has been almost universally hailed as one of the very greatest war photographs of all time. This photograph shows a Republican loyalist militiaman who has just been shot and who is beginning to collapse into death. No one had ever seen a photograph like this because the Spanish Civil War was the first in which the lack of censorship and the smallness of the 35 millimeter camera made it possible to get that close to front line battle action.

Speaker Great. OK, excellent. Sam, just why would you want to do it again? We’re having a little fun. Oh, yeah.

Speaker No, I don’t think I can do that.

Speaker I think that was if we can keep that possibly, how bad is bad?

Speaker OK, ok, ok, ok.

Speaker Eventually, they made their way south to Andalusia and it was on the front just north of Cordoba, that Cowpat, who was a few weeks short of his twenty third birthday, made what has been almost universally hailed as one of the very greatest war photographs ever made. The photograph shows a Spanish Republican loyalist militiamen the second he has been shot and is beginning to collapse into death. No one had ever seen a photograph like this before. The lack of censorship and the smallness of the 35 millimeter camera made it possible for the first time to get that close to front line battle action.

Speaker And what do we see in this picture?

Speaker Well, we see the man collapsing into death, I think maybe it’s time to go into the controversy. Yes, definitely.

Speaker I mean, we will show the photograph. I believe we see a man who’s just been shot, who’s beginning to collapse. And I think then I’d go.

Speaker All right. So so.

Speaker So let’s just let you speak about that.

Speaker Over the last 25 years, there has been a raging and thoroughly unjustified controversy about the authenticity of this picture. An accusation was made that Cowpat had posed the soldier that the soldier was only pretending to have been shot. But we now know, thanks to a Spanish historian who happened to have been present himself at that battle at Cerro Mariano on September 5th. Nineteen thirty six, we know that the man in the picture was named Federico Forell Garcia and that he was, in fact, shot in that battle that day.

Speaker And.

Speaker What or you have a theory about. Why I happened to be with this camera right in front of that guy as his moment of death.

Speaker What seems to have happened was that Kapper met up with a group of soldiers in a sector of the battle that was temporarily quiet. Where there seemed to be no imminent danger, the soldiers were running up towards the front, but without any immediate fear of being shot, they reached a trench and Kalpa got down in the trench, which is why the photograph is shot from such a low angle. He was aiming up at the soldiers standing on the rim of the trench, and it was at that moment that an enemy gun emplacement opened up and the men were shot.

Speaker Completely out of the blue.

Speaker And right. Yeah, I think that was good. It has been said not guilty.

Speaker I don’t really want. I don’t think that’s germane.

Speaker I mean, um.

Speaker Did you not say that you thought that they were kind of. Doing things for the camera before the actual.

Speaker Well, I did say that they were they were running and they didn’t think there was any danger. I think I’d like to leave it there.

Speaker OK. All right. Um, and then I’ll just ask you what. What brought about this controversy?

Speaker Why have people thought that it was.

Speaker The controversy arose apparently through a lapse of memory on the part of a British journalist who claimed that he was sharing a hotel room with Cowpat near San Sebastian. And I believe that this elderly man’s memory had simply failed him, that he must have been with another photographer at that time. Cappa was nowhere near San Sebastian before the photograph was published. And cafA did share a hotel room with this British journalist during the Spanish Civil War, but only at the end of the war in January 1939 in Barcelona and after the lapse of 40 50 years, it’s very easy for the memory to play such tricks without any sense of that. Now, let me just just just let me let me just say and after the lapse of 40 or 50 years, it’s very easy for the memory to play such a trick.

Speaker But there are others who have taken the you know, the role, the original negatives or contact sheets and compared pictures and have used those images to make that accusation.

Speaker Well, not really. I mean, there is no contact sheet in the front.

Speaker I mean, there are some, but there’s another picture of the same. Oh, OK. OK, OK. Now that yes.

Speaker Then I can talk to.

Speaker The controversy was further fueled by the fact that there are two photographs which at first glance may appear to be of the same man in two stages of collapse. But close examination can leave no doubt that they are, in fact, two different men. And what must have happened was that the first man, the man in the famous photograph, was pulled into the trench by his comrades and the second man as Capa continued photographing, snapping his camera. The second man was shot.

Speaker So there were two people then that would have been killed that day. All right.

Speaker But I guess I keep coming back to I guess you’re choosing not to talk about it, but. Well, tell me. I just think it’s really interesting that, you know, that he did how people do things for the march of time images and sometimes for Carol.

Speaker The point is not that, you know, that he never did kind of react to things, but the guy really died.

Speaker So there’s many things here. It’s not my reluctance. It’s Cornell.

Speaker All right, Cornell, we’ll just never forgive me if I talked about that. I mean, there are certain things you don’t know what I’ve been through. I can’t do that. I just can’t. Let’s move on. I mean, Cornell would never, ever let go of that. I would hear about that every day for the rest of my life if I said that on camera, if I talked about that on camera.

Speaker Still exonerating, I think we need to leave it there.

Speaker OK, that’s for.

Speaker OK, so now let’s talk about the kind of evolution of the photograph and the two of them taking pictures, and the first it was printed, it just captured, and then sometimes she would have all that kind of evolution. Yeah. OK, ok. OK.

Speaker OK, now, OK, this gets complicated, and I need your guidance here just how much you want me to go into. Do you care about what cameras they used? No. People always ask.

Speaker People always want to know what color cameras do they use and they use both skill and movie cameras.

Speaker Well, I’m thinking more that Gary used the Rolleiflex cap. OK, I think we’ll avoid that. Well, no, no, let’s stay away from that. So that simplifies things.

Speaker And you can always. Picture.

Speaker OK, OK, so let me let me let me just work with this, and it may take a couple of takes, but let me let me just try this, hone it down if necessary. So in Spain, Capa and Taro worked side by side, copper was a great deal more experience than Taro, who really was only several weeks into her photographic career, learning all the time. She was very precocious with a camera. She worked mainly with a Rolleiflex square format where Cowpat used the Leica or a 35 millimeter. So it’s very easy to tell their photographs apart. But as Gerda gained confidence, their separate identities mattered less to them, and their photographs are more similar to the point that they even decided to have a stamp made up that would say simply photo Capa and Taro. They’d really become a team, which is what Kalpa had always wanted and. The terrible tragedy, indeed, the greatest tragedy of Kappa’s life was that a very short time after he and Gerda had reached this level of professional cooperation and.

Speaker I’m sorry, I just lost I just couldn’t get a word. Uh, just we’re just didn’t come into my mind, not cooperation.

Speaker Um. Collaboration, collaboration. Thank you. Just coming out, OK, so let me start.

Speaker OK, the great tragedy, indeed, the greatest tragedy of his life was that a very short time after he and Garita had reached that level of professional collaboration, Gardas life was to come to an end. In July 1937, while Kalpa was back in Paris taking care of business affairs, she photographed a battle at Brunete, a short distance west of Madrid. And when the tide of battle suddenly turned and a. Haphazard retreat began in that chaos, garroted jumped on to a car standing on the running board on the outside of the car, holding on to the window, and the car swerved and hit a tank.

Speaker Gerarda was fatally crushed. And. Tappa really never fully recovered from her death.

Speaker How did you learn of her death?

Speaker Cowpat learned of her death. In. OK, um.

Speaker I know, I know what it is, I know no, I just want to know how to phrase it.

Speaker Kapa. Completely unprepared, learned of her death.

Speaker By reading the newspaper, sitting in a dentist’s chair, he turned the page and there was the headline.

Speaker Correspondent Gerda Taro killed at Brunete.

Speaker Garita was given a tremendous funeral in Paris, paid for by the Communist Party, who made her a martyr heroine and commissioned a monument for her from no less than Alberta Giacomini in her cemetery.

Speaker And I’m going to speak about. What can be said about the. If you lived there would have been married and what kind of marriage that huh?

Speaker Well, I don’t know about it, but um. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker Capa had certainly hoped to marry Taro, he had probably asked her at some point, but if the timing was wrong because Taro in the spring of 1937 was growing into her fame and independence as a photojournalist in her own right. And so the idea of suddenly limiting that newfound freedom with marriage was not appealing. Had she lived, they probably would have been married. And the shattering of that hope made Karpas relationships with women difficult. From then on, he found it difficult to make a commitment to a woman for fear that that commitment, too, would be shattered.

Speaker That was excellent and just to push this a little further.

Speaker I think well, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but then that he envisions a kind of marriage that would be really a partnership and one of these would later really.

Speaker Hmmm, I think we could we move on? I think I think I’m I think we know. I think we’re getting bogged down. No, seriously, we’re at the time I think I think maybe that’s something to come back and it’s an end.

Speaker And it was such a variety of it’s very hard to generalize.

Speaker And I mean to put Pinkie and Ingrid Bergman and Gemmy into either three totally different women, totally different relationships. So I really am not comfortable generalizing in that way.

Speaker It’s more like about how he envisioned his marriage with Gerta being.

Speaker Yea, but I did say that they reached that and just said, well, could we move on and maybe come out OK? I really would like to keep the momentum here of sort of the high ground here since we have limited time and we’re still in Spain and the clock’s going. So I’d like to talk some about Hemingway here.

Speaker Oh, OK. Sure, sure.

Speaker Probably the most important friendship that copper forged in Spain was with Ernest Hemingway, who was covering the war as a reporter for American newspapers and was also making a film with George Stevens film called The Spanish Earth. Capa and Hemingway liked each other immediately. They shared a an openness, a warmth and booleans of personality. But they were also very different. Where Hemingway had a streak of bullying, Capa was much more. This is this is a mess. No.

Speaker Well, no, it’s just. You know, I need you to think about that for a minute, at the beginning, it was OK, but no letter to the, um.

Speaker OK, I think I know what I was. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, much, much better, much, much more to the point.

Speaker The most important friendship that Kapa forged in Spain was with Ernest Hemingway, who was covering the Spanish Civil War for various American newspapers and was also working on a film called The Spanish Earth with the Dutch director, George Stevens. Capa and Hemingway. Shared a fascination with four. But their approach to war differed greatly, Hemingway looked upon war more as an opportunity to test himself. Cowpat didn’t need to test himself, Karpas covered war out of his political commitment to do that sentence again. Cappa covered war out of his political commitment. He covered war as a partisan, he once said that he was unwilling to risk his life to cover war unless he loved one side and hated the other.

Speaker Great. OK. That’s OK. You were saying and maybe you could just say their friendship, the friendship continued. OK. OK.

Speaker The friendship that began in Madrid lasted until Cooper’s death. The men would see each other from time to time in New York, in London and Paris. There was great warmth, though, also a lot of tension between the two men. But it was certainly an important friendship and a very gratifying one for both of them.

Speaker Do you think that would care about gambling before this point? Seems to me that was after his death and that the poker player.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, I was thinking about that. And it does seem I wonder if it wasn’t maybe on the ship to China. That’s really the beginning. Those endless weeks at sea seems to be before then. There’s there’s really no mention of his gambling. And he talked. The first mention I can think of is where he talks about gambling is when he says he won his English in a crap game in Shanghai. So I think it was China that began the gambling.

Speaker Do you can you imagine that there would be any kind of connection between losing Garita and.

Speaker I hesitate to speculate quite like that.

Speaker I think that’s one more thing, back to back to the Garden State death in the making, the book that went.

Speaker But that was what that meant.

Speaker Oh, wow, gee, what do you have in mind? I mean, there’s so much else I think I mean, isn’t it? Don’t we want war with the Spanish Civil War meant to him? That’s what I’d like to talk about next. I think. I think. I think. Yeah, I think that that’s. Although Capa was photographing the Spanish Civil War on assignment for various French newspapers and magazines, and many of his photographs were eventually published in Life magazine, which began in the fall of 1936. Capa would certainly have gone to Spain in any case, even without an assignment. Spain was his war. It was the first opportunity for the men and women of his generation to confront fascism militarily. Until then, it had all been frustrating talk some street battles. But Spain seemed to offer an opportunity to inflict a decisive defeat upon fascism, perhaps, ideally, even one so decisive that the international fascist movement would be discredited and collapse.

Speaker So then the outcome of the war, how did that affect.

Speaker Thousands of young men and women from around the world went to Spain to volunteer for the Spanish course soldiers, ambulance drivers, doctors, nurses, for all of them. Spain represented an end to fascism with its virulent anti-Semitism. This was, they thought, the last chance to prevent the war that was so obviously on the horizon. So the defeat of the Spanish republic was the most devastating defeat imaginable. Because to these people now. The cataclysm was clearly upon them, their lives, the their whole position in the world was in the most profound question.

Speaker Great. That was great. And how did you guys going to China connect to that? Why did he want to go to China? What was happening?

Speaker The war against fascism in the middle 30s was being fought not only in Spain but also in Asia. In 1937, Japan invaded China and because Japan was allied with Germany, that invasion came to be seen as the eastern front of the international war against fascism. Capa had thought about going to Spain with Garito when she was still alive.

Speaker He said, Spain is sorry. Sorry. Yeah, I should.

Speaker Capa and Taro had talked about going to China together, but after Kennedy’s death, the idea became much more appealing. The cappa could work far away from the war that had killed his lover. And so he connected up with George Stevens, who was going to make a film in China to be called The 400 Million. Coppo went along to shoot stills and it was not a happy experience. From the beginning, the film crew was carefully watched by Chiang Kai-Shek censors. They were denied access to many of the stories, many of the people they wanted to film and photograph. In his frustration, Capa turned to one idea to stand above the herd of photographers by shooting and color. Great novelty at the time. Since in the 30s, most editorial photography was black and white. Color in most magazines was limited to advertising bought. Kodachrome film was invented in the mid 30s and a 35 millimeter version of it was placed on the market in thirty six. Thirty seven. Cowpat had heard about this, so he wrote to his agent in New York for some of this film, which he proceeded to shoot after a Japanese air raid on Hankel. The pictures were published in Life magazine, and I believe they may very possibly be the first color photographs of war ever published.

Speaker Great. That was really great.

Speaker I wonder if you’d be willing to comment on the connection of too hot to handle being so ugly, uh, in some ways similar to China’s romantic or photographer.

Speaker Hmm.

Speaker OK, it’s so complicated. And what was first and second and who and but you can say what the movie was and, um. OK, well there is that. There is. OK, I know what to say.

Speaker Oh, yes. And I hear it.

Speaker Capa was such an extraordinary person that his personality attracted great attention and he began to gain some celebrity quite early on, a very unusual thing for photographers at that time when photographers were often not even given a byline. But he had been one of the first to change that dramatically, even getting his name splashed across the front page of a magazine carrying his photographs. So when he was in China, his name appeared from time to time, even in the gossip columns of New York newspapers, which may have had something to do with the similarity between Kappa’s rather glamorous personality and a Hollywood film starring Clark Gable called Too Hot to Handle, in which Gable plays a newsreel cameraman with very intriguing similarities of appearance and behavior to capture.

Speaker Can you can you just maybe give it a couple of examples of those similarities are.

Speaker What emerges is the photographer or cameraman as a an inspired rogue who was terribly cool under fire, irresistible to women, and after a night of shooting, a battle would retire to one of the local luxury hotels for a glass of champagne for breakfast.

Speaker And there’s a lot of probably well, I forgot that, I forgot that this move on, let’s move on. So.

Speaker Let’s go back to Afghanistan, where we go back to Spain, or at least I think we’ve kind of done Spain. OK, so go back to Paris.

Speaker It’s thirty eight.

Speaker So, well, why he left Paris.

Speaker OK.

Speaker At the outbreak of World War Two in the fall of 1993 to start over again.

Speaker First of all, was it for summer? It was August.

Speaker Joanna, what was the date of?

Speaker After the fall of Barcelona in January 1939, Kaper returned to Paris, which had become very much his home. Christopher Isherwood, who had met Capa on the boat to China the previous year, remarked that he thought Capa was more French than the French. And the observation is very apt because although Kalpa would eventually become an American citizen, Paris was his real spiritual home for the rest of his life. But the comfort of that home was greatly disturbed. Later in 1939, when on September 1st, Germany invaded Poland, thus launching World War Two at the outbreak of the war, the French interned many foreigners, many French people who had been associated in any way with the communists, and Capa felt himself in considerable danger. So he began making efforts to leave Paris, to leave France and make his way to the United States, to New York, where his mother and his younger brother, Cornell, had settled.

Speaker So how do you get there?

Speaker Kapa. Arrived in New York by ship, having crossed the rather dangerous Atlantic safely, but he woo, woo, woo! Where am I leading?

Speaker Well, where am I going? All right, I, I. What are we doing with this boat? Yeah. So what do you what do you want me to do here? I mean, how quickly do we go to get to New York?

Speaker And I mean, do you want to do that, that the greatest war photographer in the world found himself without work or without interest in it was reduced to shooting what was what we call cats and dogs stories to want to do that get to that because.

Speaker But then he couldn’t get to the border photographing. Right, right. Right. That’s what we want to get to that. And then.

Speaker Well, I think maybe we should just get right right to it, because really having arrived in New York, he wanted to get back. He wanted to get his his papers and an assignment to go back to cover the war.

Speaker Great. OK, so let’s.

Speaker But then let me just think.

Speaker How much are you going to do with Mexico and Mexico? We really need to talk because a natural transition would be.

Speaker Well, I like that because I like what you said as of yet another front in a certain way of of.

Speaker Yeah. And yet for dramatic expediency, it would make sense to go. He got a New York attorney or he wanted to get accreditation and an assignment to go back to cover the battlefront. Couldn’t found himself stuck and even a marriage of convenience to become a naturalized resident didn’t help, couldn’t get an assignment. And things became even worse after Pearl Harbor when he was actually an enemy alien. So there would be that natural flow without being interrupted by Mexico. All right. All right. We’ve had enough. Yeah, I think Mexico. Mexico. Yeah. It’s it’s not that. It’s very complicated and I think it’s maybe better skipped. So it may take that it’s still a little complicated. Let me try, but let me see if I can if I can say what I just said. OK, OK, let’s see. So where do I need I need to start with the fall of Barcelona. Right. I need to go back or. No. Oh no, no, no. I got up to New York right where where his mother and brother were. OK. OK. I don’t need to say he came by ship. Do you care? No, no, no. Yeah. Well, that I mean, that was in a bed in the section we’re not using. OK, so.

Speaker OK, ok. I think I got it. Really, everyone OK?

Speaker Having arrived in New York, his first priority was to get back to Europe, to cover the war, to get his accreditation, to get an assignment from Life magazine or another major American publication to cover the war in Finland.

Speaker And woops, let’s see. So we’re all right. Yeah. OK, let me talk. OK, let me just, uh. So, um. I want to say the world’s greatest.

Speaker OK, so OK, no, no, let me just. I think I’ve got it.

Speaker OK.

Speaker Having arrived in New York, Kappus first priority was to get back to Europe to cover the war, he had been acclaimed at the end of the Spanish Civil War as the greatest war photographer in the world. And yet in New York, he found himself in a terrible predicament. He couldn’t get accreditation. He couldn’t get an assignment. The greatest war photographer in the world was reduced to the indignity of what were then called cats and dogs. Stories for Life magazine. Trivialities very frustrating and matters grew even worse after Pearl Harbor, when, as a Hungarian citizen and Hungary was allied with Germany, Capa was technically an enemy alien. So his hope of getting papers to go to Europe were almost nil or would have been nil for any normal person. But Capa was not to be deterred. Marshaling all his resourcefulness, he managed to get to Britain and hoped to use that almost immediately as a stepping stone to the fighting in North Africa. Instead, he ended up spending nearly a year and a half in Britain, doing some very interesting stories. But it was still a period of great frustration for him.

Speaker And it would be good to talk about this marriage, because that was one way they was trying to get these.

Speaker I think that that’s important. You want to go back to that? OK.

Speaker Um. Really?

Speaker Yeah, just for the very day. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh.

Speaker It was just it was just a marriage of convenience, oh, I think. Let’s move on. I think I think we’ve got we’re we’re doing OK. And and it’s also a little tricky.

Speaker And I would even check with the lawyers about, uh, uh, bringing Toni Cherelle, if she’s alive, she’s she’s a tough, tough lady.

Speaker I think you need to make sure that it’s all right to mention her to give her name or anything. She could be litigious.

Speaker OK. All right. Um. Oh, but, you know, one thing that happened when he was in Mexico was the hurt that I love that line where he says. And the world was never as it is now. Oh, we can we can get together tomorrow.

Speaker OK, so we’re in World War two, North Africa.

Speaker OK, yes. All right. Now, Waterloo Road, was that his first trip to England?

Speaker I’ve just I’ve just conflated the two, right?

Speaker Yes, I definitely do the Battle of Waterloo Road.

Speaker I can talk about that, we can talk about that. What interests you?

Speaker I just that while he was in London, you got the pictures.

Speaker What made a book create a book with with someone. OK. Oh, ok. Oh.

Speaker During his time in Britain, Koppa photographed not only the life of the British Londoners specifically who were trying to carry on again after just a say, I’m sorry, I want to say that he he focused on the British Battle of Waterloo Road and but also on the Americans. Mostly what he did was American troops and flyers.

Speaker Um, do you want me to go into that or not? No, no. Just you just need to find that that’s. The major work to emerge from Kappus Time in Britain was a book called The Battle of Waterloo Road with a text written by Diana Forbes’ Robertson, whom Cowpat had met in Spain. The two of them worked very well together to win the confidence of Cockneys in the east end of London, people who were bearing up under the destruction of the blitz that had nearly destroyed most of their neighborhood and cowpat focus on one family particularly that represented all that was strongest and most determined most by.

Speaker That’s right.

Speaker Uh. OK, um, yeah.

Speaker Oh, OK. OK. Let me let me do that again.

Speaker The most important work to emerge from Karpas Time in Britain was a book called The Battle of Waterloo Road with a text written by Diana Forbes’ Robertson when Karpas had met in Spain in the book. Cowper and Fort Robertson focused particularly on one family, the Gibbs family, a Cockney family in the east end of London, a neighborhood that had been particularly hard hit by the Blitz. And the Gibbs family represented very wonderfully, very dramatically and powerfully the undaunted spirit of the British. How the blitz, far from demoralizing the English, as the Germans had hoped, had in fact done just the opposite. It had rallied the British spirit to prevail.

Speaker That was great, because then we’re going to interview one of the kids, girls that will go, OK, that’s great. OK.

Speaker All right. Let’s talk a little bit about North Africa and what what what what about North Africa? Well, you might want to skip North Africa. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker And I think one of the specific things about Italy, which is that he was there and that is he spoke very eloquently at one time about the pictures he took there and this and then going particularly to the vulnerable pictures.

Speaker I think you said these with a real the more of the tape, I have the truest pictures of my truest pictures of victory.

Speaker Yeah. Mm hmm. That’s that would be the end of this.

Speaker OK, after the allied victory in North Africa, Cappa went on to cover the invasion of Sicily and then onto the mainland, where he did some of his most powerful work, Copper clearly felt very much at home with the Italians. And he. Covered the liberation of Naples, and it was there that he he came upon a funeral that was particularly heart wrenching. A group of high school students led by one of their professors had raided an arsenal, gotten some weapons and had harassed the Germans as they were retreating from Naples. The Germans had killed most of these boys and the funeral was taking place at their old schoolhouse. As Capa photographed the grieving parents and the hastily assembled coffins that were too small, even for these boys, he said that these were his truest photographs of victory, that although he loved photographing the exuberant celebrations of troops being welcomed into Palermo, it was pictures like these that told the true story of the cost of war.

Speaker Great. That’s great. You want to comment on it might be confusing the audience with Italians, the enemy, but at the time people were thrilled to be allied with Hitler.

Speaker OK, contextual thing.

Speaker By the time Cupper began photographing in Sicily and then in Italy, the Italians were quite fed up with the war and thoroughly disillusioned with their German allies. So Kapur found the Italians, for the most part, very friendly to the Americans and surprisingly happy to be taken prisoner by the Americans, because that meant that for them, the fighting was over.

Speaker Great. That’s excellent.

Speaker All right, so let’s get him back to England waiting for D-Day.

Speaker OK, OK.

Speaker Everyone knew that the great story of the war, the turning point of the war would have to be the opening of a Western Front by means of an invasion into France, that that’s as close.

Speaker But I can do a lot better than that.

Speaker By the spring of 1944, everyone assumed that an allied invasion of France was imminent. The Soviet Union had been calling for a Western Front for years to take the pressure off the terribly beleaguered Russian people. And Capa looked upon the invasion of France not only as the war’s possibly greatest story of all, but also as the liberation of what had become his adopted country. It was a very personal story.

Speaker Uh, that’s good, but. As good as I can do that, just let me let me focus, I’m just trying to shape where I’m leading with that.

Speaker Um, so filmis to the horror of D-Day. Yeah. His words speak to that. You’re going to introduce.

Speaker Yeah. So you’re going to quote you’re going to have narration from his. OK, so I don’t need to do that. That’s good. Just do it or I can have the narrator.

Speaker But you know, yes, this was about liberating France and it got to that point, um, maybe you could just say he was one of the three, whatever it was.

Speaker Well, OK. Yeah, I think. Yeah, OK. Uh, almost, uh, dangerous. Yeah. Yeah. Oh, OK. Um.

Speaker Yeah, I think I just don’t want to talk about the Soviet Union and all that we just do by the by the spring of 1944, uh, invasion of France was was imminent. And people that gathered in London, I think, keep the Soviet Union out of it. That was that was too complicated. Um.

Speaker By the spring of 1944, everyone assumed that the invasion of France was imminent. Journalists from all of the allied countries gathered in London waiting for the great invasion. It was a time of intense partying, a sense of eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we may die. And Capa was certainly one of the liveliest of the partiers and the most reckless of the gamblers at that time. And his gambling continued when it came time for the invasion. But it was not reckless gambling for Cappa. The invasion of France was not only one of the very greatest stories of the war, but it was an intensely personal story. It was the liberation of the nation that had become his adopted home. And it was the turning point in the war against fascism, the beginning of the end, the beginning of victory in his great lifelong struggle. And for that, he was willing to put his life at the ultimate risk, to be one of the first to go in in the front wave of troops landing on one of the most dangerous stretches of the invasion beaches, Omaha Beach, on what was to become D-Day, June six, 1944.

Speaker Great, and then I’ll go into his. His words, excellent. OK. Of course, thinking about how much detail to go into and then let’s just get right to the person also, Michelle, it’s kind of a wonderful but you can do that with that narration, I think better.

Speaker Let’s get to the liberation of Paris, because there is so much for you for him in that.

Speaker And of course, the sniper is going to wait, everybody.

Speaker Well, we still have the niggled is waiting to be in world. The first was when he was one of the first. He was one of the first.

Speaker That’s kind of a wonderful choice.

Speaker Paris was Kappa’s home, the liberation of that city was, he said, one of the most joyous days of his or anyone else’s life, and he was among the very first to enter Paris with the vanguard of the French armored troops who were given the honor of liberating their city. He encountered the most joyous reception crowds in the street.

Speaker The party interrupted.

Speaker Uh, so. So and I use joy as a couple of times, though, what did he actually say?

Speaker It was the most. The most glorious day of. OK, let me just. Was almost nothing to about, um.

Speaker Paris was Karpas home. And the liberation of that city, Cowpat felt, was the most joyous event of his life, the French army troops that led the liberation joined by Kalpa.

Speaker That got very tangled are OK.

Speaker So I think what am I doing was great. You were starting to say I was starting to introduce the sniper fire.

Speaker Yeah, yeah.

Speaker And that that really threw me because the party was was set on fire from collaboration’s. Yeah.

Speaker Whew, good thing I stopped for about a minutes.

Speaker Could be, could be doorbell would be a lot better. Well, Prue, any idea what that is? Is that your drones, bill? I think it’s important. OK, yeah, I’ve got it. I think I think I’ve got.

Speaker So what is the.

Speaker Paris was Kappus home, the liberation of that city was one of the most joyous events of campus entire life, the population of the city turned out in the most enthusiastic numbers to welcome the French troops, which Kalpa had joined as they spearheaded the liberation of the citywide celebrations were rather drastically interrupted at several points by sniper fire. But within a very short time, the French had control. And in a sense, Cappa may have felt briefly that the war was over for him. It wasn’t. There were still some very hard stretches ahead.

Speaker Great. That’s great. OK, so we like to have the story of the Battle of the Bulge almost killed and adjusted and then parachuting across the board. OK.

Speaker OK, let me talk about the Battle of the Bulge. Um.

Speaker I guess the theme there is the danger that he kept the continuing danger his life.

Speaker Things like that and that.

Speaker Well, out there, yeah, well, I think the let me just try something and see if this works for you using using that, but just incorporating it into something else. Throughout World War Two, Capa found himself really loved by the American soldiers and officers whom he met, he was a good man to have around many of the unit units.

Speaker Oh, OK. OK.

Speaker Throughout World War Two, Kalpa was welcomed by American soldiers wherever he visited them. He made friends immediately. Many units even came to regard him as a good luck figure that if they had Bob Kalpa with them, things were going to go well. But that luck and that welcomed by the Americans failed him during the Battle of the Bulge, when his Hungarian background and accent served him ill. He was stopped on the road a number of times by Americans.

Speaker And the that it’s OK. You don’t need to go into all that.

Speaker Security was very high during the Battle of the Bulge. The Americans had heard that many Germans were infiltrating behind their lines, and so they questioned everyone. They stopped with problems that only an American would be able to answer who just won the World Series, that sort of thing, because Capa had no idea and his Hungarian accent only made matters worse. At one point, nearly getting him killed when a soldier approached him and across a field and heard that accent and was sure that he had captured a live specimen of an enemy. And fortunately, Cowpat asked the soldier to look in his breast pocket where there was a letter signed by Eisenhower himself, let’s say, passé for Kalpa. And that and that alone saved his life.

Speaker Great. Oh, that’s great. All right, now, how did you come to be able to parachute off the right? The fact is, I get the fact that he trained you. How OK. OK.

Speaker Parachuting had held a fascination for Cowpat ever since 1935 when he saw a story in a French magazine about parachute training in the Soviet Union.

Speaker OK.

Speaker Kaper had been fascinated by parachuting ever since 1935 when he saw in a French magazine a photographic story about parachuting in the Soviet Union. He tried to get a visa to go to Russia to photograph that school and had had failed. Instead had photographed a French parachute training school he had some years later, then photographed on the plane carrying parachutes to Sicily. And one of the American soldiers about to jump got talking with Cap on the plane and a soldier asked, are you telling me that you don’t have to be here? And capacity, yes, that’s right, I came along voluntarily and the soldiers thought about this, and just before he jumped, he turned to Kalpa and he said, I wouldn’t want your job is too dangerous. As he jumped into Sicilian anti paratroop fire, trapping himself finally had the opportunity to jump in March of 1945, he was trained and outfitted with full gear and jumped across the Rhine with the troops leading the invasion of Germany.

Speaker And. What do you think those photographs of people being shot in the trees earlier or were those all from this time?

Speaker Because when we do hear about that or you know.

Speaker This was an extremely dangerous mission, the worst of it being that some of the parachutes got tangled in trees rather than landing in open fields. And the men who were suspended helplessly were the easiest possible targets for German snipers. Copper, fortunately, landed in open field, caught his breath, picked up his cameras and began working on one of the most powerful stories of the war.

Speaker And again, why is it almost. He’s from him because six years.

Speaker Capa’s photographs on the ground in Germany.

Speaker Let me just start over that look at that.

Speaker Capa’s photographs of the ensuing battle capture in a very raw way, the chaos of the fighting, the gliders coming down uncontrolled, some of them crashing, turning into mangled wrecks. It was a very difficult battle in which a great many German prisoners were taken and Capa photographed them. The really pathetic quality of so many of the men who were fighting this tailend rearguard action of the war.

Speaker Great. OK, you know what else, I would love to just talk briefly about the fighter, the sniper in Leipzig. Pictures.

Speaker Oh, OK, now, how much do you want me to go into? You have quite a bit in your notes about the the. Yeah. So tell me how.

Speaker I think it’s interesting that you may have been the last man killed.

Speaker He wasn’t that. Oh, no, that’s that’s complete. That’s storytelling. It wasn’t even it was his last man. He never claims it was the last man. It was his last man photograph.

Speaker It was. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker Well, I’m just thinking that so I think we should move ahead and maybe move ahead.

Speaker Let’s go on to without that line, it’s not that important.

Speaker Yeah, OK. Yeah. So, yeah.

Speaker Although I wonder if Matt well, you know, does it make any difference. OK, um, I’ll cover that, I’ll cover that for Magnum and. But yeah. OK.

Speaker OK, so now what is it that interests you, particularly in Russia.

Speaker What do you want to accomplish there. I mean I think I’ve read that he wanted to show that people were people the world over.

Speaker Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Why Americans are so interested. And um. And then also the repercussions of having gone to Russia just as the Red Scare was heating up. OK, what was Steinback is important.

Speaker Kapa had wanted to go to the Soviet Union since the mid 30s.

Speaker No lubrication, yeah, yeah. I think even a little.

Speaker Just to pulls the trigger 200. As long as it doesn’t shine. No problem. OK.

Speaker Of the No.

Speaker Since the mid 1930s, Cowpat had applied several times for a visa to the Soviet Union, but had always been turned down. So when John Steinbeck, whom Kalpa had met during the war, I said that he had been invited by the Soviet government and that he could take along a photographer as a friend. Kapit jumped at the opportunity. Steinbeck was invited because he was the American writer whose works were held in highest esteem as a kind of American version of socialist realism. So he was given a hero’s welcome on the red carpet, was laid out for him and by association for Kappa Kappa.

Speaker After the war wanted more than ever to go to the Soviet Union because.

Speaker The war had hardly ended before the Iron Curtain came crashing down, the Soviet Union was a closed territory, a great and threatening mystery to people of the West. Americans in particular. And Capa was given the unique opportunity to photograph in a very direct, personal way the life of that country. He wanted in much of his post-war work to make the point that people are essentially the same all over the world. People are people, whether they’re Russians or Japanese Americans. And he loved that aspect of the Soviet Union, though it was certainly one of the most frustrating periods of his life. He was blocked in many ways. He was censored. But the trip produced a very fine book, which Capa Capa’s photographs were joined with Steinbeck’s text. Great.

Speaker Excellent.

Speaker And then just if you just wait for the science disappears, it’s gone away.

Speaker OK, OK, OK, it’s way in the background and you still hear it, it’s way back, but I saw on this tape. I think it’s usable because it was so good, I don’t know. OK, ok, ok, OK. Just the the I don’t know, the. Aaron said he was met by the FBI.

Speaker Oh, I don’t know about that sounds, but I would say OK.

Speaker In the long run, the trip to the Soviet Union certainly added to Karpas troubles in the 50s with the American State Department who suspected him of being what was called then a premature antifascist. And I should explain, but let me let me let me go back.

Speaker And I didn’t say that quite right. But I made the point.

Speaker OK.