Speaker When I started going to the ballet in the mid 40s, I must have been 12 or 13 and my mother took me to ballet theatre, the first ballet I saw was Jazelle with Markova Andolan, a very famous. At that time, I didn’t know what was going on. There were these old ladies with little wings on their backs and they were hopping around on their toes. I thought it was insane. So then she thought that didn’t take she’d take me to something for boys. And they had at that time at Ballet Theatre, a program for boys, a matinee. And on that program was Jerry’s fancy free Agnes Daniels Radio and Loring’s Billy the Kid. So this was supposed to be very exciting, but since I was a very bookish boy who never went across the street alone, stories of the Old West and sailors at loose in Times Square were not exactly relevant to me. However, I saw something to it. It was it was fun in a way, but it didn’t catch me. And what started me off was when I was 17, just before the New York City Ballet became the New York City Ballet, it was still a ballet society. And a teacher of mine took me and a friend to one of the last performances of Ballet Society. And I saw Balanchine and that was it.

Speaker What was American value like in those days?

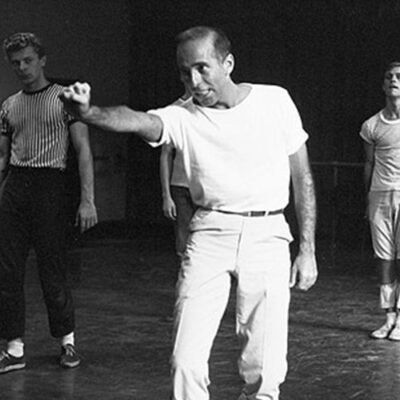

Speaker Well, what I saw, I can’t say was symptomatic because in the mid 40s, what did I know? I didn’t know anything. I had no context. I remember fancifully very, very well. It was the best of those ballets, obviously, and still is the best of those balletto. And it was the original cast. It was Jerry. And oddly enough, the first dancer I ever met years later was Janet Reed. And she was totally wonderful in her British way. And you could see what the Brillo and the excitement of it and the freshness of it was because it was life that was going on outside in the street at that time. It was during the war. There were sailors in town. Everybody was on the town and they were on the town on. It was then called fancy free. So I remember Jerry very clearly in it as being a. A fascinating. Performer, I couldn’t have articulated any of this at that time, but if I have remembered this for whatever it is, 60 years more, you know, clearly he made an impression. I then saw him later at Ballet Theatre. I can’t swear to anything, because when you’ve studied a lot of ballet stuff and you’ve seen a million pictures, you’re never quite sure whether this is something you’ve seen when you were 15 or whether it’s something you’ve seen pictures of and you think you’ve seen. It’s like family albums, photograph albums. You think you remember the picnic on the beach. But what you remember is the picture of the picnic on the beach. But I think I saw Jerry in Helen of Troy. It was very, very different on the one hand, there were. Ballerina’s, you know, old fashioned Russian only Russian type ballerinas and on the other hand, there was this impulse toward Americana and freshness and populism. It was then what it is now, a big mixed bag. There’s never been an aesthetic dominating ballet theatre. It’s just been stars in vehicles. And sometimes it’s great and sometimes it’s ghastly. Jerry was a very effective performer. Of course, I saw him much more frequently when he joined New York City Ballet, and those were the years of his amazing performance and prodigal son, which was wrenching. And particularly also I remember him in Borey, fantastic in the movement with Taxila cleric, his great friend Tony, and how charming and witty and brilliant they were. And he was an trancing performer. He was not a classical dancer, as we understand it. And I don’t remember I never remember seeing him in classical roles. I’m sure he did them because he had to do them. There was nobody around. But that was not his history. You know, who’s a little like him. I’ve even written this is Craig Sulston at Ballet Theatre today.

Speaker You know, he’s full of energy. He’s over the top. He’s full of Briere. He gives it everything he’s got. And then more so, you know, is he does he have perfect feet, you know, before?

Speaker So before OK, so before we get all fancy free, could you tell me why I realize you’re here? This is not something you knew at the time. It’s something you can tell me now. Why was it important for its time?

Speaker I think a lot of it had to do with a new kind of energy that seemed to reflect the world that we were living through at that time. Everything’s changing. Was the war. New York was changing in many, many ways. Part of it came from just this very subject, the servicemen who were coming through all the time. But also there was a freshness of approach. There was nothing stuffy about it, nor did it have that kind of self-satisfied Americana quality that a lot of works in the 30s had. There was nothing overtly populist about it. You know, it just seemed to be happening. Here are these guys, these three guys, and they’re on the town, you know, and they pick up these dames and everything goes screwy and they have. And yet it was a classical ballet with these brilliant solos of wonderful duets. Everything about it just worked. How do you explain that? Some ballets work and most ballets don’t work. And the reality is that that was his first ballet, probably his best ballet, and probably the one that has performed the most and will go on being form the most.

Speaker Um, was there anything else excuse me one second.

Speaker Do you talk to me outside the door?

Speaker Was there anything else that you had to say about Gerry’s performance and fancy free?

Speaker I couldn’t remember more than that. That’s fine.

Speaker Um, what how would you characterize Robin’s role in the Americanization of ballet?

Speaker I have to think about this one. The Americanization of ballet. The question of Americanization ballet is a complicated one. What do we really mean by that? We don’t mean what I think people did mean in the 30s and maybe the 40s, which is in relation to subject matter, who cares? Know, as Mr. Balanchine said in his ballet of one of his American ballets, it isn’t a question of subject. I think the real Americanization of ballet was done by Balanchine when he recognized in young American boys and girls a new body type, a new energy level, and something that he could use to adapt and extend classical technique. Because before these American dancers, whom he eventually trained in this direction, people couldn’t do the kind of things he felt could be done and wanted to do. That was the Americanization. It was had to do with body and technique rather than subject matter or music. Balanchine, of course, found many American topics, as we know, Stars and Stripes and Who Cares, etc. But I don’t think that was the point. Those also were classical ballets with American material.

Speaker But in some way, Jerry must have had a part in that, not only because of the subject matter, but also because of the fresh energy that you talked about, or I think he did.

Speaker I think Jerry had something to do with that in the same way that Agnes de Mello did. They were two of a kind. She was, of course, the elder, and she made her impression earlier. But she, of course, also was classically trained and wanted to be a classical dancer. She wasn’t a classical dancer any more than he was. Maybe they came to a two later in the wrong way with the wrong training. Who knows? That it was an impulse we had to show them that we could do it. Also, we were cut off from Europe through the war years. You know, there wasn’t any European ballet for from 1939 till 1945 or thereafter. The ballet Roo’s was touring around the world. So they were coming through, but it was mostly Russian. That was the idea of ballet was Russian. And this was one of the things that Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein were always dealing with. You know, ballet didn’t have to be Russian just because it had been Russian and because George was Russian. I don’t think he thought of it, that he thought of it in terms of classical. But classical didn’t begin in Russia. It moved to Russia first from Italy, then to France, then to Russia. America was changing. America was becoming the center of the world. And whereas we in essence, invented modern dance. Coming in to the extent that anybody invents anything but, you know, coming from Isadora Duncan and with, say, Dennis and then on into Martha Graham and the people we now know, that was seen as American, even though there were major European modern dancers like Bigman, that that was American. But ballet was over over there. That was Russian, that was European. And once Balanchine had committed to America, which he did very quickly and forever and passionately, he didn’t want that anymore. He wanted it to be American. Look, American, smell American. He wanted to be American, as you know, with his Western clothes and his passion for cops and robbers and all the rest of it. But the process was in training and in American physical capability and everything followed from that. And I think Mr. Miller first and then Jerry and then some of the Broadway choreographers, other ones added to that Fed that it grew. So there became what looked like an American style of theatrical dancing and ballet dancing. After all, Balanchine spent many, many years on Broadway for Rodgers and Hart shows that’s not Russian. You know, he was instantly adapting in the 30s to America, American dancers, the American stage, the American atmosphere. And then he was in Hollywood. You know, you don’t work for Goldwin in 1937 if if you’re not in touch with America and somewhere having enjoyed fancy for you must have been exciting to see on the town.

Speaker I was thrilled by on the down people going to ask me to strike again because I didn’t.

Speaker Oh, I’m sorry. OK, one of the great theater experiences of my life was the Saturday matinee when I saw on the town the week after it opened because I was a Broadway kid is to save up my allowance. And on Saturdays I’d go down to the 40s and for a dollar twenty you could buy a second balcony seats. And that’s what the reviews had come out. Nobody pre bought in those days. So you’d go down to the theater and there would be long lines waiting for the show that had just got all these reviews. As I remember it going back, God knows that’s seventy or sixty years or whatever it was on the town, I think played at the Adelphi Theatre. You can check that. But I think it was a Philadelphi Theatre. There was a long line. I got my ticket and about two Saturdays later I was there and I had seen the hit shows like Oklahoma, but I’d been taken to and life with father and other things too. But this show was the witty, sophisticated show of its time. Its what pal Joey must have been a few years earlier. But I was eight then, and when the curtain went up and these bright, fresh people were there, it was completely ravishing. First of all, the score was wonderful. But what did I know from scores? I mean, I like the music. I was a musical kid. The performers were so wonderful. Comden and Green were so wonderful. Sono Asato were so ravishing. Everybody was wonderful. Nancy Walker was so funny. But best of all, there was this feeling that you were in on something new. And of course, when you’re a kid, particularly in those days, the whole idea of being sophisticated was very important. I felt I was there. You know, I was present at the creation of this. Then years later, to my astonishment, I turned out knowing and even working with many of the people from on the town that was like a insanity’s.

Speaker If anyone would suggest that to me, I thought they were crazy. But of course, I worked with Jerry on and off for years and come and green and etc., etc. So and Seona, whose book I edited, so I but it was a wonderful experience, a wonderful show, and none of the revivals have ever done it justice. And I’m not quite sure why it doesn’t seem to translate to our time, but it was a sensational.

Speaker What was new exactly about it from the energy?

Speaker Well, it was very New York. It was bright. It was about clever people. It wasn’t sentimental. I mean, of course it was sentimental. All musicals are basically sentimental, except maybe some of Sondheim’s it had an air about it. It was like a Hepburn Cary Grant comedy in the 30s. You felt you were in the presence of people who were smarter than you and funnier than you and wittier than you and who knew what was going on. And we’re having a great time. That was part of it. Everybody up there seemed to be having a fabulous time. And you wish you were one of them.

Speaker Now, another show I think you enjoyed very much was Jerry’s was high button shoes.

Speaker Well, I remember high button shoes, mostly for the dance. It was not a great score, although was pretty good score. But the famous no, the bathing beauty is no. The beach number was rightly famous. It was completely, hysterically funny, brilliantly put together. It just worked from the first moment to the last moment. You watch these the cops, the Keystone Cops and the girls and darting in and out. It was like a French farce, except it was on the beach and it was a musical. It was a complete success that no has certain numbers can be, you know, stand out. I mean, we usually think of showstopping numbers as Ethel Merman belting out Rose’s turn, but they can also be dance numbers. And, you know, and what Jerry did, for instance, in the Uncle Tom number and the King and I was exactly the same. It was a showstopper stopper. No one had seen anything like it. It was so ingenious. They were ingenious. You know, his he was clever as well as capable. He knew how to put things together, but he also had original notions to put together. So it wasn’t just a big combination of things that had already worked recycled. They were they were new. They were exciting.

Speaker OK, and the next one before we get before we go to ballet, um, is I think you also saw of mom dancing originated.

Speaker Yeah, I remember almost nothing about look, mom dancing. It wasn’t that I’m the third girl in the second row and the fourth act of the fifth movement or whatever.

Speaker You remember anything by any chance about Nancy Walker’s performance?

Speaker No, I just remember seeing Nancy Walker a number of times. And all those times are conflated into one time because she was brash and funny and lively and pleasing. And you adored her and she got away with everything.

Speaker OK, so, um, you you talked before about when you began to frequent the New York City Ballet, but I wonder if you can tell me how the company was different then than it is now?

Speaker Well, the New York City Ballet in 1948, which is when I started seeing it, which was its first year, was, first of all, a much, much smaller. There weren’t many dancers, so everybody danced two or three times a night. You know, it wasn’t somebody turns up on Tuesday night and then made dance again Thursday night. You not only danced once, you danced thrice. And that was great, you know, because you really got to know these people intimately. Also, there was very little audience.

Speaker So to a large extent it was we happy few at the city center. I was starting in the second balcony. Then you’d sneak down in. I think everybody knew everybody was sneaking and was sort of pleased because it made it better for the dancers to have a good audience closer to them. The repertory, of course, was much smaller because he hadn’t made all those ballets that he made after 1948. It was the new pieces that came in that had just been invented. Previous to that moment were Symphony and C, which he made in Paris but quickly brought to Ballet Society Orpheus, which was then a major work which everybody was knocked out by.

Speaker It’s lost its force and I think it lost it when it moved to the State Theatre, which was too big for it of. What else was there? He slowly brought in his old repertory, but, you know, it wasn’t even prodigal son at first, Prodigal or Apollo, they came in. I may be wrong about Apollo. I’m certainly right about protocol, which he has, you know, I’m sorry. I’m sorry. Which he revived for Jerome Robbins. And then we revived for Frank Momsen and then Rerise revived for Eddie Valhalla and eventually Baryshnikov. It wasn’t there. We saw the same ballets over and over and over again, which made for great familiarity with them. And you could do it in those days because that was before the state theater, which means it was before there was a subscription so people could pick and choose and you could run a ballet every season endlessly because you weren’t dependent on a subscription in which people could say, well, I saw that ballet last season, so I don’t want to see it this season. Then, of course, the big events in the early years were First Firebird, which was what really put the company on the map.

Speaker Tall Chief’s performance in The Firebird made New York City Ballet famous. Every this was the first hit that everybody had to see, not just Balanchine lovers or serious ballet goers. And the next in 54 was The Nutcracker. And you know its history because everybody knows its history. It gave the company financial security to the extent it ever had it, which wasn’t a very great extent in those days. It was beg, borrow, a steal. And I think George did all three.

Speaker Very soon after the company was founded, Jerry asked Rotha Balanchine, right, and asked if he could come and Balanchine said yes. And shortly thereafter made him the associate artistic director. Why did he do that?

Speaker Well, we don’t know why. We don’t know why bouncin did anything because often he didn’t care why he did something. He just wanted to do it and thought it was the right thing and did it. And he didn’t question himself in the question of Jerry coming. I think even if he had not articulated the reasons to himself at that point, he knew what Jerry could bring.

Speaker And in fact, he once told me years and years later we were talking about Jerry, who was wanted this and that and etc. in the following years programs. And George said, you know, dear, give Jerry what he wants. You know, he wants all rehearsal time. Good. He wants leading dancers. He can have I can use the others. I can do it. And other times, though, where he said, you know, if it’s not so good, what I do, I make it better next year. If it’s not so much better next year, I do something new. Jerry good company makes hits. Audiences come. Give him what he wants. That’s the essence of it.

Speaker He felt that Jerry I think obviously he admired Jerry’s work or he wouldn’t have had anybody there whose work he didn’t admire. But the point was that Jerry was connected to a different audience. And had a popular point of view that he felt would be useful to remember in those days, New York City Ballet was considered very, very elite. It was high toned. Only snobs preferred New York City Ballet to those wonderful Russians and good Arab Jazelle Ballet Theatre was dishing out that era. And I think Balanchine realized when he made ballet is like Firebird and The Nutcracker that he needed the company if it was going to survive and grow to a larger and larger scale. He needed to attract an audience and Jerry was part of that. Now, whether he sat down and thought that through, I have no idea. I didn’t know. And then I wasn’t around at that time. But it makes sense. And Jerry did do that. So it and who else was there, you know, if he was going to compliment his own work with that of somebody else, he didn’t need a clone of himself. He needed somebody other. And Jerry was that whether he sensed that Jerry could make classical ballets? I don’t know. And I don’t know that you could say Jerry did in the traditional sense of classical ballets. He certainly never made ballets like a symphony in C or ballet imperial.

Speaker Given what we know about Jerry’s insecurities and you knew him fairly well, why do you think he made a decision to and he’d had his by that time fancy green all the time and so forth. Why do you think he decided to put himself in a place where he was always going to be the runner up?

Speaker Jerry was a very complicated person and his impulses were in more than one direction. He wanted to be a huge Broadway star. That was very important to him, success was very important to him. Money was very important. All these things that Bouncin really was not interested in bouncin, was interested in one thing. What’s happening on stage? What can I do? How can I move it forward? How can I help this dancer? How can I grow this dancer? What can I do that will take ballet a step further? Jerry wanted success. He wanted power. He wanted money. He wanted security. But he also was very, very smart about dance. And he recognized, I’m sure, more quickly than most people around at that time that Balanchine was the overwhelming genius in this field, probably in the history of dance, of ballet dance. And he wanted part of that. He wanted to learn from Balanchine. I believe he wanted to be Balanchine, but he didn’t want to be those other things that Balanchine was you know, he wanted it both ways. Well, that’s human. And Balanchine wasn’t quite human. You know, he was he was Olympian, which doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a very human side to him that could gossip and bitch and carry on and be spiteful and all the rest of it. But an artistic level. He knew he had no peers. He knew he had no rivals. Jerry was in no way a threat to him. He could absorb Jerry. He was very clear about Jerry’s work and what it was. I remember once.

Speaker Sure, I remember once. Roger, you OK? Yes. Yes, I OK.

Speaker I remember once I was with the company in London and we were for some reason at the Colosseum, not at the Opera House that season. And I went in to the theater one afternoon to watch rehearsal. There was nobody there in the audience except Balanchine who was watching, and it was a rehearsal of Jerry’s Four Seasons. So I sat down next to him. We’re watching, we’re watching, we’re watching was in practice clothes. And I said to him, I said, you know, this ballet is better than people think it is. I’ve always liked it. It’s I think it’s a whatever I said didn’t matter.

Speaker He didn’t need to hear what I said. But the point is, he said to me, yes, he said good ballet. He said, you know, I tell Jerry, get rid of all those customs, get rid of that said, just let them see what you’ve done with the movement. They’ll see how good it is.

Speaker But he didn’t want to hear that and he wouldn’t do it. So but his ballet. So he was watching Jerry. I never felt that Jerry was watching George.

Speaker How would you characterize Jerry’s relationship with Lincoln?

Speaker Well, I never witnessed it, but they were going to ask you to go back and just say yes.

Speaker Yeah, you. I never really witnessed Jerry and his relationship with Lincoln Kirstein, but it was not a happy one for the most part. Lincoln was very dismissive of his work, at least privately. And I think Jerry felt he was a.. Robbins and I think he felt the same way about the company manager, Betty Cage. They were not on very good terms either. So but I can’t witness I never witnessed anything.

Speaker Excuse me. Because apparently Lincoln was very, very supportive of Jerry early. Something happened. I don’t know what it is.

Speaker Well, you never know with Lincoln what would trigger what, because sometimes it was something major and sometimes it was something minor and sometimes it was something that hadn’t happened. And, you know, particularly before his bipolar ism was, if not conquered, at least mediated, it could happen like that, you know.

Speaker There’s very little that stands for as a record of Jerry’s dancing, and you started to talk before about protocol.

Speaker I would love it if you could talk some more about that performance.

Speaker I remember most the anguish of the crawl off stage at the end. There was tremendous brio at the beginning when he comes out of the tent. He didn’t have the spectacular. Technique of either Villella or Baryshnikov. He probably was closer to live, far the original, he was sensitive. He was, as he was about, brash and sensitive as Jerry was. Maybe we could say he was more Jewish than Villella or Baryshnikov, but he certainly made a tremendous impression. Now, I also have to remind myself that this was the first prodigal son I ever saw. So it’s also the ballet made a tremendous impression on me. And the ballet has changed in some regards, but that’s a whole other story. But he was deeply moving in this ballet. You felt very exposed. He exposed himself in it. And Jerry did not go around exposing himself publicly. I think that’s why it was an important performance for him as well as for us. The other one you started to talk about was for a fantastic February fantastic, which is a charming ballet, has been mostly out of the repertory for decades. Once in a while, it turns up again, was done at the school a couple of years ago. Miami City Ballet is doing it now. Ballet Theatre did it at one point, but never for very long. I don’t know why it was a big hit when it was done. You know, it’s French. It’s got wonderful, glamorous costumes. It’s full of movement. It’s a big company work. And it had fabulous performances, you know, very difficult, interesting role for Tallchief. And then this iconic part for tackle the Clark and Jerry. They were so witty, so they were so close personally, which added to the fun of it. They knew each other inside out and upside down. And you could see it. They were it was like the two of them were just implicitly having a lot of fun up on the stage and everybody else had a lot of fun. That was the high point of the ballet that what it’ll look like today. We’re with different levels of capability in the different roles. I don’t know. Also, they were favorites. They were audience favorites. Everybody loved them.

Speaker I don’t know how would you describe Tany in the ballet, in this ballet, boy, Otani Leclerc had a quality that no one else has approximated in her iconic roles, of which the most famous Lovell’s. And in this and in almost everything else she did, there was an elegance with.

Speaker A Frenchness. And also.

Speaker Don’t mess with don’t mess with menas, you know, she obviously cared tremendously about dancing, but she didn’t care what you thought she was going to do, what she was going to do. And if you didn’t like it, too bad. Of course, everybody did like it. The only thing I can think of in which she was really unsuited was when he gave her Swan Lake. That didn’t live long. We used to call it Ebisu Pool because she looked so odd in it.

Speaker But she was a thrilling dancer, you know.

Speaker In in her role in ORFEUS, the second movement symphony, and see, no one’s ever really been better, people like Allegra Kent and Suzanne Farrell were as interesting, but this was her role. She like the physically well, she was tall and thin, lanky, elegant. It was all elegance and humorous. You know, cynical may be too strong a word, but sardonic is the right word. She looked at everything. SARDONICALLY She wasn’t cute or saucy like Janet Reed, she wasn’t a powerhouse like Maria Tallchief.

Speaker She was unique.

Speaker You know, balancing in those days, everyone always says he like he rubber stamp dancers, he wanted them all like looking like bouncing dancers. This is one of the most stupid things said about him. What he wanted, of course, was very it was dances with very strong personalities, but by personalities. It was dance personalities, not facial personality, not playing with the audience or playing to the audience. He wanted dancers who looked like themselves and he could then mold out of those selves the very distinctive roles he created on them. He could never have made had he made Lovell’s or Borey on a different ballerina, it would have been a different ballet. He used those qualities. So if you want to know what a dancer like Leclerc was like, you have to look at the ballets that were made on her. And the same is true of Tallchief and Allegra, Kent and Pharrell. That’s how you find out what those dancers were like.

Speaker And another ballet that Jeri’s that made a very big impression and that brings up another dance. Could you talk about the impression that made on you and the dancer who started.

Speaker Jerry wasn’t the only person who was a refugee from ballet theatre or an explorer from ballet theatre, you know, his great friend Nork came, Diane Adams came, one of the most important figures in those years in New York City Ballet and New York City Ballet. Nora was a dramatic dancer. She had made one of the great sensations in American ballet in Tudors Pillar of Fire at Ballet Theatre. She was the great dramatic dancer. Again, she wasn’t really a classicist, although she got up there and Swan Lake drowned. The body wasn’t really right. Didn’t matter. She had an intensity and a power that were absolutely extraordinary. And she and Jerry were very, very close personally and indeed almost married when he created a major work for her, which was the cage to Stravinsky score. You know, it was a sensation. First of all, it was all about what appeared to be bugs, and she was a. a black widow, something devouring, murdering the men who came her way, even the one she was sort of interested in. But too bad. But her buddy, you know, it was a very brilliantly put together piece.

Speaker Very carefully crafted to be a sensation. It’s very short and it holds up a lot of dancers have danced the role successfully, which is a tribute to the role it didn’t need.

Speaker Norrick. No one has ever been as good, really as strong, as powerful. But it doesn’t matter. It holds up as a ballet. Is it a ballet that today I want to see over and over again? Not really, because it doesn’t take you very far. Once you’ve seen it, once you’ve had the sensation, the shock, there’s not much more it can do for you. It doesn’t reveal anything very human or very important. It’s just a brilliant piece of theatre. And this is something that is very important to understand about Robbins’, I think, although he gave up Broadway for the New York City Ballet to a certain degree, he never gave up a Broadway mentality. He was interested in hits. He was interested in being seen as a hit maker. I remember he would he was more interested in.

Speaker Saturday night performances than in matinees, because the kind of people he was connected to and wanted to impress were Saturday night opening night people, they weren’t just people with families who came to the theater. So for him, creating a hit was important. Now, it was important for Balanchine because he understood that the company needed a hit to survive. So that’s why we had as I said, that’s why we had Firebird Nutcracker eventually Jools Vienna waltzes. These were all meant to be hits and were hits and they were big audience sensations. Jerry needed hits to prove that he could create hits and so that his world would understand that he hadn’t thrown himself away on art. But the other side of him was that he also needed to be modern, adventurous, artistic. And so we got works like the Goldberg Variations and Watermill in which he could be an artist. To me, those are far less interesting and effective works.

Speaker And the audience found that to excuse me. I think what you’re alluding to in all of this is his sense of theatricality. Yes.

Speaker No, I’m not talking about his obvious and brilliant sense of theatricality. Balanchine had tremendous theatricality to, you know, when the lights go up at the end of Vienna waltzes, there’s nothing more theatrical than that. It isn’t a question of theatricality that was always at Jerry’s fingertips and was one of his great, great talents and wonderful it was to know this had to do with his sense of himself as someone who was successful and made successes. I think that was very, very important. Just as the other feeling, I am an artist, I have to explore. I’m modern, I’m keeping up. I’m going to use a Philip Glass score. I’m going to use Japanese elements in Watermill. That was important to him, too. He wanted to be cutting edge, but he wasn’t cutting edge. He was a step behind, cutting edge, learning where he could from cutting edge bouncin. Didn’t know what he was he wanted. Oh, he heard this music. Thought that would make a nice ballet. It was by Chhabria. OK, we’ll make Borey fantastic. Or he was impressed by Japanese performance. He commissioned a score and he created Buga cuz it’s a classical ballet in Japanese, but he didn’t do it because he wanted to impress people with his modernism or avant garde isn’t it. Interested him. And so he did it. Jerry was always had an eye on his reputation and how he stood in the theater world and the dance world bounty. He knew where he stood in the dance world.

Speaker But when you talk about I’m not trying to be argumentative, but I’m sure when you talk about peace like water, I mean, these are not popular hits. You couldn’t possibly have thought that Watermill was going to mean he was going to be, you know, king of the hitmakers know. How do you reconcile those two aspects?

Speaker You see, these are the aspects of him that are, on the one hand, Broadway and on the other hand, avant garde are two different things. He wanted them both. And sometimes you can have your cake and eat it, too, and sometimes you can’t. The ballet he was most offensive about was Goldberg. I experienced that myself during the years when I was programming the ballets for the company. This was the ballet he was most protective of.

Speaker How many times is that going on next season? Why is it going on? A two man is why, after six performances, why are there six performances? If you overexpose it, people won’t like it. If you underexposed, it means you don’t like it. What do you have against Gober?

Speaker This went on every year and I would every year try to explain to him that under the subscription plan that the New York City Ballet was employing, by that time there were sixteen subscription series and you could only show about two to one subscription once. And then it had to rest, so if you have 16 subscription series. And you have three seasons, that’s five more or less a season. You can do fewer than five, but you can’t do more than five more than once, and since we also had some non subscription performances, you know, he didn’t want to hear this because he had to feel beleaguered in relation to this particular ballet. So he clearly was very, very. Anxious about it and about its reception, I think he felt this was a major opus with great artistic leap forward for him and he didn’t understand the less than brilliant reception it had in many quarters.

Speaker Um, since I just like to get back to New York City Ballet history, um, and since you’re so familiar with the history, could you tell us the fact that what happened to Tanneke, first of all, and what the effect of that illness had on the company?

Speaker You know.

Speaker One of the great blows to the New York City Ballet, one of its great tragedies was Tanika blacklegs getting polio while the company was on tour in Europe. It happened in Copenhagen. At first, no one knew whether she would live or die. It was devastating. It was devastating to the audience, which was all I was part of at that time. The fact that this brilliant, fabulous, unique creature was never going to dance or for that matter, walk again was just overwhelming. Nobody could really take it in. At first, it didn’t seem likely that she would live. So Balanchine stayed on in Copenhagen with her. Actually, it turns out later, ironically, their marriage was already in difficulty. However, that was irrelevant at that moment. And he brought her home and stayed with her. And for a year he stayed away from the company. He made no ballets. He didn’t take class or rehearsal. He just took care of her. Well, it was a devastating blow. And everyone rallied round and did what he or she could.

Speaker When he finally came back, it was with a tremendous burst of energy and he made four ballets in ten minutes. It seemed they all came out within weeks of each other. It was all building up in them. But she was irreplaceable and he never replaced her to the extent. That he found a dancer and we could look at in some of the same ways, it was another friend, the real Frenchwoman, Violette Verdie Tany, was French, but she grew up in New York. Veillette was Paris Opera trained, and she was a French dancer. But she had wit, musicality, style. She looked nothing like Tany. Her effect was nothing like Tany, but she took up a little of that slack in those difficult years when Tallchief was moving out of the company, when Tany was gone. Diana Adams, whom he adored, was a nervous, anxious dancer.

Speaker And Alegra was growing. That’s what that was the period when Alegra was thrown into everything as well, she might have been because she was ravishing in every way. But Tony has never been replaced and in her roles, even today, where there are terrific performers, whether it’s her movement in Western Symphony or in Lovell’s, in which a number of people have been wonderful.

Speaker There’s never been one who made as much of it, in my view.

Speaker But, you know, what good does it do to say that there’s very little on film, what there is is very persuasive. With Gerri, you know, afternoon of a fawn was made on her and she was completely wonderful in it. Other people have been wonderful and it’s a perfect ballet. It’s a perfectly made ballet and it has suited many different kinds of dancers. See the last movement of Western Symphony, for instance, or the second movement of very fantastic. They are very specific to Tany and her qualities. Afternoon of a Faun can be really any beautiful, talented dancer. Within certain limits, obviously, it doesn’t have to be her personality, you know, so I would say that is the ballet, although she was glorious in that she is at least missed in. Of her major roles.

Speaker What do you say farm’s a perfect, perfect, perfect, because it does everything that he wanted it to do, it’s it’s about something. It’s about it’s easy to say. It’s about narcissism and answers, but it’s something deeper than narcissism. It’s an involvement with knowing that what your job is to look right, to seem right, to convey the right thing out of yourself. It’s about being looked at and doing. And then it’s about the moment when between these two young people, something else happens. Life intrudes for an instant and breaks through and then is withdrawn from because ballet can’t sustain that.

Speaker Well, as a metaphor, you see most dancers that are metaphors are just that, but this is a metaphor with the material of the ballet justifies it. It is what it’s about and it’s about what it is. And I’ve never seen it fail. I’ve seen much better performances than other performances, but I’ve never seen a performance that didn’t signal to me. This really is as far as it goes, perfect. Does that mean it’s a great work of art? I don’t think it’s on that level because its ambitions aren’t that large. But so what? You know, everything can’t be King Lear. And luckily, because if we had to see nothing but King Lear, we’d be dead of exhaustion and emotional depletion. So I would say it is his most perfect ballet, it and fancy free. But there are a lot of the others I like, but I don’t think they succeed on that level where you don’t want to touch a hair on their heads.

Speaker Before we leave, Charlie, do you have any notion of what Jerry’s response was to her illness?

Speaker Only from what I’ve read in the biographies, which was that it was a catastrophe for catastrophe. Sorry, only what I’ve read in biographies, which is that it was a catastrophe for him artistically, but far more personally. And he was loving and attentive to her for the rest of their lives.

Speaker Oh, the letters that have been revealed to us in Amanda Veil’s recent biography are just overwhelmingly moving the depth of their connection and their ability to reveal themselves to each other. They’re very important documents humanly as well as Dansa. I think it was a tremendous attachment and that he was devastated. You know, Gerry, in real life, as opposed to dance or work, unless work is real life and the rest of it isn’t, who knows? But in real life, he was tremendously kind and generous person. You know, if you were a dog, a child.

Speaker A cripple, an old lady or just, I guess, a friend, you know, he was constantly there for you, thoughtful, sensitive. Helpful. It was only in work where he obviously felt threatened that he was not quite so adorable.

Speaker So he heartbroken, left the New York City Ballet for a while after this period, and he went to start a very fertile period on Broadway.

Speaker So I’d like to talk about that a little bit in the years when you, you know, excuse me, I’m not the person who should be talking about this. That’s fine. I just am not. I don’t know enough. I don’t care enough about Tanny. No, no, no. About this Broadway part. You know what I’m talking about. I don’t have anything to say.

Speaker OK, could you talk about and you can say no, but could you talk about how musical the the place that musicals had in American culture in those years when you started going and in the years when Jerry was working there? That’s different than it is now. And just in terms of cultural history, not terms of Jerry specifically.

Speaker You know, Jerry, when he went back to Broadway, he really reinvigorated the musical. Now, the American musical has been on and off wonderful almost from the start, including all those silly shows that we now poke fun at. Like No, no Nanette or yes, yes, evet or whatever they were called. You know, the Rodgers and Hart shows were great. The stories weren’t particularly great, but the scores were wonderful. The choreography, at least in the Balanchine years, was terrific. Obviously, the performances were terrific. And then when Rodgers and Hammerstein started during the war, that was a whole new wholesome, romantic, but very useful and very effective thing. It’s easy to poke fun at Rodgers and Hammerstein, but, you know, Oklahoma is a fabulous show with one of the great scores. Look, go back to 1927 and Showboat. There’s never been a better score and a more effective musical than that, which is why everybody goes on reviving it all the time.

Speaker But Jerry brought into it later a different kind of energy and wit and passion and devotion and dedication and obsession that really raised the level and not just of steps, but of concept, because that’s what he was. He was a conceiver, you know, and that’s why shows like West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof are very different in kind from the kind of vehicles that Rodgers and Hart, the Cole Porter that Gershwin created for the Broadway stage, their concepts.

Speaker And a lot of them really worked. And some of the shows that he didn’t really conceive of, like Gypsy, his work was fabulous.

Speaker You know, Gypsy is a great, great musical, maybe the greatest Whoknows. They’re all the greatest. The great ones are the greatest when you’re looking at them or listening to them. What’s happened now, there is no person like that around for a while, Harold Prince was conceiving of brilliant shows. Sondheim was creating major shows that changed everything except that he changed everything. But nothing changed because what we’re getting now are canned shows on the home that you you know, they’re they’re company shows, you know, the Disney musicals, the Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals. I don’t know what these things are. They’re not fresh. They’re throwbacks or they’re empty. Now, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t very clever new shows on. I haven’t seen them all, but I gather they’re very good. I have no sense that they’re on the level of these these others. And I don’t think there are performers on that level. I happen to tune in to some merman cuts from Gypsy the other day by accident. I was blown out of my seat. I mean, there’s never been anyone like that except Kirsten Flagstad, you know? And then there will be that’s first of all, you can’t have that anymore in my theaters. Nobody has to sing that way anymore because the mic is doing it for them.

Speaker So I’m going to skip wherever, skip the Broadway stuff. You have better people on the OK.

Speaker So after a hiatus, eventually Jerry has to return to the New York City Ballet. Tell me what was going on in the company at that time that made it actually an opportune time for him to be there?

Speaker I think any time would have been opportune for him to come back. I think what was opportune was that he had it building up in him. He was ready. He had done what he had done on Broadway. I think he was tired, probably. I see in those days I knew him only vaguely socially. I wasn’t yet involved with the company. So I was an outsider socially. I knew him, as I say, slightly. But you could sense that he he had there was nothing else he needed to do on Broadway of that time. And of course, the vision of Balanchine was always before him. And I think he never felt disconnected from the company. After all, it was still performing his ballets and he was still, I, I’m sure, deciding whom to cast and what it should look like and making himself felt.

Speaker And I think Balanchine was delighted to have him back, and as you know, when he started to make dances, the gathering, it wasn’t meant to be an hour long ballet. He made a few things and he asked George to look at them. And George said, you know, good God, keep going more. Give us more and more and more. And it grew. And it grew. And it grew.

Speaker And it was one of those great hits, you know, and it was wonderful. We hadn’t seen anything like it. The music was wonderful and very well chosen. He had 10 superb dancers, when you ask yourself why doesn’t dancing to the gathering look as good today as it did, then just look at the cast. Not that there aren’t good dancers today, but they’re just not on that level. These were the major dancers of a great ballet company at its peak, and they were thrilled by the newness of it and the excitement of it. It also hit at the moment when Suzanne Farrell left for five and a half years and Balanchine was down. So it was good that we had Jerry there.

Speaker You know, he didn’t really make anything for a while. Balanchine then he made who cares. Then came the Stravinsky Festival that gave the company its other great new charge. So the miracle of the Stravinsky Festival, with Balanchine making three major works in no time at all and everybody else making a lot of not major works before we move on from dances together.

Speaker I wonder if you can tell me what was a little bit different about it. What was remarkable about it in its time here?

Speaker Ten people came on stage and dance the gathering, one at a time, starting with Edward Villella as the boy in Brown and his relationship to the ground, to the earth, to the sky. It was set outdoors somewhere in some abstract outdoors.

Speaker It was about dancers again, like as in the afternoon of a fun. It was about dancers gathering in a place where they were at home or had been at home and what their feelings were about it, about dance, about each other, how they come together, how they separate, how things go right, how things go wrong. Parts of it were sad, plangent, other parts were joyous and full of fun, people bonding, people abandoning each other. It seemed that had that thing the jury could sometimes do very effectively, which is make you feel you’re there. There’s a there’s a there there. And the dancers. Are there any other now sometimes that became pastiche in Jerry, it seemed as if he was almost parodying himself. But in dancers at a gathering at the beginning, it all worked. And it was anchored by these superb performances like Patti McBride as the girl in Pink Velvet, Villella, Alegra, you know, these were great, great dancers. Today, it’s tame down. There were a lot of physical difficulties and dancers at a gathering. Those throws in the big the three couples part those throws at the end of it, they were terrifying. I remember once that we all thought Sally Leland was going to be dead because she was flung across the stage and she was caught about two inches from the floor. They’re not doing that anymore. Now. They sort of hand the girls to the boys. It’s sort of ridiculous because this is the this is the dynamic crisis of the ballet and it doesn’t take place in the same spirit. Part of the reason was that people did indeed keep getting hurt.

Speaker You know, Jerry’s lifts were famous for doing damage to ballet dancers. And I remember a point later on when I was involved, when Balanchine had to tell him to tone down some of the lifts, he said, I don’t have any boys who can dance anymore. They’re all out. Their backs are all out because of these lifts. We can’t afford them. So Jerry had to tone them down. You know, he didn’t care. He wanted the effect he wanted and what it did to the rest of the company, the rest of the world was not his problem because he didn’t have the responsibility for the rest of the company for the rest of the situation of the company was in. And I don’t know whether he really cared. The company for Jerry was two things, I believe. One, it was Balanchine. God. And the other was it was a place for his work to be seen, and that’s what he was going to protect. That’s what New York City Ballet was for, Jerry.

Speaker Tell me a little bit about your role in the company and how it came. What what what was your official role company when you actually you were there on an official basis as opposed to just being in the office and when?

Speaker My official connection to the ballet, as opposed to being one of the maniacs who loved it from the first day, came about sometime in the early or mid 70s. I was then running a publishing house, Alfred Kropp, and I was editing several major books by Lincoln Kirstein, and we became very friendly. He took an interest in me, as he did in a lot of people who he thought could be helpful to the company. And he asked me one day whether I would join a new board of directors that he was creating because he was finally succeeding in splitting away from the New York City Center board of directors, a unique board for the ballet company. And this was going to be six or seven people. And would I be one of them? And, you know, I said, you don’t want me on the board of directors because, A, I don’t particularly like rich people and B, I can’t raise money. And he said, no, no, you don’t have to raise money. You know, I need you there because I need someone there who’s knowledgeable about the company and who will be there at the moment of crisis, which meant, of course, the moment when George would die or retire. So I said, great, anything I can ever do for the New York City Ballet, I will do so. I was now on this small Chami board of directors. I’m not much of a board of directors person and I tend to get off them faster than I get on them. But I became much more friendly. Therefore, with the people at the company, I began to know them and he he arranged for me to meet George and I became very friendly with Betty Cage, the company manager, and Betty used to have dinners on Monday night.

Speaker She was very close to Lincoln and she gave dinner parties for people he wanted to have around him, whom he either liked or felt could be useful. And I started going to a lot of those dinners. And one night everybody was whining about why people weren’t coming to the matinees. Why aren’t people coming, bringing their kids to the matinees? And I said, Lincoln, do you really think the parents are going to bring their children to see Buga cuz one of the most erotic ballets ever created. And he looked at me in that fiercly and he said, You’re interested in programming help, Betty. So I had an assignment. That’s all I’ve ever wanted. So within six months I was doing the programming for the New York City Ballet, which I went on doing for about 10 years or 12, I don’t know, through the rest of George’s life. And then for some years with Peter Martins has a very complicated job, because not only are the subscription problems where everything is, but you have to know the repertory inside out. You have to know the dancers you have know music. You have to confer what you have to confer with the stage manager. You have to confer with the ballet mistress. What can get on in a certain period of time anyway? It’s a very complicated thing, just my thing, because I love puzzles and games. So I was doing that very happily for many years.

Speaker Meantime, what had happened was that the New York City Ballet had been essentially a mom and pop store. A very few people were involved with managing it. There was Betty, there was Barbara Morgan, George’s personal assistant, there was Eddie Bigelow, who did everything, maybe some money people. There was nobody.

Speaker There was a press person. There was a this person. There was there was no administration really didn’t need it because there was this little thing at the city center scrimping and saving up its dime so that it could afford something. After the move to the state theater and the subscription and various other things that happened, it became big time. It was suddenly one of the great cultural institutions of America and for that matter of the world, artistic institutions in the world. But it’s still had nobody running it. And the people who are running it, certainly Betty was getting older and she’d done it already and her energy was not failing, but it was dropping. There was no one to pick up the slack. No one was being trained. There was no new management. So because I will do anything that needs doing, I would have some costumes if I’d known how I started to take on more and more responsibility because there was no one doing it. So I started to oversee not just the programming but the whole marketing, because after all, programming is connected to marketing, someone has to oversee the ads, the brochures, the general face to the public. So I took on all of that from my office as a cop and then I got very involved with the labor negotiations. With the orchestra, that was months and months and months there was a strike.

Speaker So in your official capacity as the programmer, let’s say, New York City Ballet. Could you tell me how you interacted with Jerry and what that was like?

Speaker Every season and there were two a year before I started programming, I would drop in on bouncin to discuss what was going to be in the next season. Now, he didn’t care at all which ballets of his were in and which were out. He’d seen them all. He’d been with them all year. He didn’t even notice. Really, what he cared about was music he wanted. He loved to hear certain music performed. But what I mostly needed from him was knowing whether they were going to be new ballets and what they were, because if he was going to make a 35 minute ballet with a big finale, that’s a closer. If he was going to make a bright, charming little piece, that could be an opener. It was going to be highly dramatic. Maybe it would be in the middle. So if you’re putting programs together, you need to know the kind of ballet it’s going to be.

Speaker And to the extent that he knew, he would tell me that whole meeting took five minutes because there was nothing to say. He was more interested in the photographs I chose to put on the brochures and in the ads there, he had strong feeling. No, there is no arms. Legs look like spaghetti. No, no, no. So Jerry was different. First of all, I didn’t go to see Jerry because life is too short.

Speaker I would call him and already he would be on edge because he knew someone was out to get him and I would say, Jerry, I’m thinking of bringing in A, B, C and D because we have to retire E, F, G and H, because they’ve been in for the last three seasons right away. He would be on edge. I don’t understand why that has to come out. We’ve only had 14 performances of it in three seasons, I said, because there’s no room for it. We’ve had 14 performances. That leaves two places where it could go. It has to rest for three seasons. Already there was trouble, but on the whole there wasn’t trouble because he wasn’t stupid. He didn’t want to get that point, but he got that point. It was just that it had to be reiterated every year. He was very defensive and protective about the Goldberg Variations. That was the ballet he was protecting above all others. He on the one hand, he felt there were never enough performances. On the other hand, he was upset if there were too many performances because then it was overexposed. He didn’t like it on matinee days because he didn’t really care about matinee days. He would have been happy if he could only have been performed Saturday nights, every Saturday nights, maybe Friday nights, because that’s when the Broadway gang would turn up the non elite ballet people, but important people. Well, there were only a certain number of performances you could do of Goldberg Variations. First of all, it’s very long. It’s hard to make a program out of it. Second of all, sorry, Jerry, audiences didn’t like it.

Speaker However, we would get through that. We had only one real difficulty, difficult moment, which I think is a very telling one, and that is one season.

Speaker He said, oh, by the way, would you tell George that I am planning to revive Scherzo fantastique. This was a small ballet he had made for the 1972 Stravinsky Festival for JLC Kirkland and for boys.

Speaker As I remember, it wasn’t very good and no one thought it was very good. But it wasn’t my place to say that. So I said, sure. So I called up George and I said, Jerry asked me to say this. And the only time in my years of dealing with Balanchine. That I ever heard him come down hard and he said, you tell Jerry I won’t have that ballet on my stage. OK, this was not a message I was looking forward to delivering, however, I can’t say it was my job, but it was my responsibility.

Speaker So I called Jerry and I said, you know, Jerry, I mentioned schizo fantastique to George. And he said he really would rather not see it revived. And Jerry blew a gasket and he said, I don’t understand that it’s a perfectly good ballet and I’m going to do it and I want to do it. You tell George that I really feel we should do it and I want to do it.

Speaker And at that point, I thought to myself, no, so far, but no further. And I said, you know, Jerry, I think if you feel so strongly about this, you should tell George yourself. Now, what’s fascinating is that not only did he not mention it to George, but after George’s death, he never proposed it again. George had said no. So for a long time, I wondered, what is this what was this about bouncin didn’t care.

Speaker We’d seen worse ballets by Jerry and others on the stage. What did he have against this in particular? And then I realized what it was. This wasn’t just some ballet. This was to his Stravinsky. And he wasn’t going to have second rate work of Stravinsky as shown on his stage. I think that suggests a lot about the relationship between the two of them, George, you know, let him do let him to up to a point and then and Jerry would say, oh, well, I want I mean, I need up to a point. And then and there was no argument.

Speaker Did she ever discuss Jerry or his Ballies, other values of his Jerry’s with you?

Speaker Gosh, you know, it would have been glancing remarks like he didn’t much like. That was let me think for a moment. What’s the ballet to the Prokofiev Violin Concerto? Oh, no, no, no. Oh, maybe no.

Speaker Yeah, I got it. Opus 19, Opus 19. Slash the dream. Is that what it was called?

Speaker The Dreamer.

Speaker George George only mentioned specific about right, I’m sorry, George only mentioned specific Robbins’ Balasz to me in glancing remarks, nothing I would have really remembered. I remember one disparaging remark about Opus 19, The Dreamer. He thought that that score could have been better employed, although Balanchine had no liking or respect for Prokofiev, who had treated him very badly over the prodigal son. But no, he didn’t. He didn’t talk about the sea with Balanchine. Everything was practical. He would talk about something if there was a reason, if, for instance, I had said we have a problem with this aspect. Of other Robin’s piece, he would have addressed it. I do remember one of the one thing that worked the other way, which was I was very concerned that there was no backdrop to bounciness ballet Lassus, which is a small ballet made at the city center, which looked swallowed up on the stage of this tape. And I kept saying to him, we really should have something behind it, which and he said, yes, yes, yes.

Speaker And finally he agreed to that and he decided he could use part of the abstract set from the Four Seasons. He said, I think that would be good. I’ll ask Jerry. And Jerry said, no, Jerry would not let part of his set for the Four Seasons be used by Balanchine in a Balanchine ballet. So George said, all right, we find something else. And I think he eventually used the backdrop for Raimunda Variations. He will. But again, that was that a novelty of Jerry’s. This is mine. I’m not giving it up. I’m holding onto it. It’s mine.

Speaker Such a contrast with the generosity that he exhibited in other areas. Absolutely right. Oh, this is a big question, but see if you’re willing to have a go. Somebody who is intelligent but perhaps uninformed about the ballet world. How would you describe just simply and in general the difference between the Balanchine aesthetic and the Robin’s aesthetic? And what I’m talking about is Balanchine’s what I’m trying to get at is maybe there’s another way of going at it is the notion that Jerry made ballets which were primarily about ideas. And Balanchine really made ballets that were primarily about music and dance.

Speaker And feeling.

Speaker You know, I don’t know that I can address this in two minutes, I’m not sure I could address it in two hours.

Speaker You know what I’m talking about in terms of Jerry? I mean, if you want to do it just in terms of Jerry, that’s fine to.

Speaker You know, I feel that for perhaps less sophisticated audiences, the Robins ballets seemed an easier way to get into appreciating dance. They were more realistic, whatever that means. They were simpler. They seemed to be less based on classicism and steps than they were about real life people, ideas, notions people felt. I think at ease with them. They didn’t make tremendous demands. Now, of course, Balanchine didn’t either. And he would have said he didn’t. He would say, you know, just you don’t have to know anything. Just look, if you like it, great. If you don’t close your eyes and listen to the music.

Speaker But Jerry was more available.

Speaker I think he wanted to be, except when he wanted to be experimental. But also it was his nature. He grew up that way. He can grow up to be a classical dancer.

Speaker You know, he didn’t grow up in Russia and there wasn’t an American ballet world. When Jerry was growing up, what was there? There were a lot of Russian companies and a few little things around. There was the School of American Ballet. But he wasn’t part of that world. He told it the way he knew it. And that was the way a large part of the audience knew it was not against him or against the audience. Whether we can say that Robin’s ballet has eased audiences into Balanchine ballets, I don’t know, because after all, a lot of Balanchine ballet ballets are huge audience hits. You know, you don’t need to be encouraged to have a great time at a lot of Balanchine ballets.

Speaker It never affected me that way because my.

Speaker First revelation was balancing everything else in dance has always seemed additional to me, not that there aren’t other great geniuses and not that I don’t appreciate a lot of Robin’s work. But if it didn’t exist, it wouldn’t exist, whereas if bouncin didn’t exist, we would have no Ballay today, there would be nothing know as the world has come to understand.

Speaker But what about the notion that German values about ideas? We’ve talked about this that day when we all sat around that at a roundtable. Remember the. Yes, we talked about the notion that Gerry tended to start from an idea as opposed to Balanchine starting from music because the opposite was also true. That’s right. Yeah. But if you were to generalize very often had an idea before he started the ballet that was apart from the music and the dancing.

Speaker You mean I’ll make a ballet without music? That’s an idea. It’s a notion I wouldn’t grant at the rank of an idea.

Speaker You know what I mean? It’s OK. Let’s call it a conceit.

Speaker A conceit, a concept.

Speaker I’m trying to think through. The Robbins’ can well take.

Speaker Let’s take an afternoon of a fawn, Jerry has told us he had a glimpse of the kid Wallowa in the studio and he was at School of American Ballet working in front of a mirror. And that gave him the idea of a boy in practice clothes. That’s an idea. So then he saw how that could be afternoon of a fawn. So I don’t know if that’s starting from an idea. It’s starting from yes. Something caught him. A conceit, a concept, a notion. An image caught him. I don’t think Balanchine started ballet is that way. Now, Balanchine could start a ballet by thinking and I don’t know whether this is what happened. I love A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I can make a ballet. We have the Mendelssohn music. But, you know, look at it this way, Jules. What’s that? If it’s not a notion now, it doesn’t mean that when he came down to it, it doesn’t come out of the music. But we’re told all the time that he was at Van Cleef and Arpels and he saw these jewels and he thought had, you know, rubies, emeralds, diamonds make ballah. That’s just as much a conceit. So I don’t know that it’s fair to make a distinction between the two men. There is a Balanchine did everything about you that did everything for every different reason. I think most of it came from the music, but also it came from what does the company need now, Jared?

Speaker And think that way he thought, what do I want to do? What’s going to be good for me? I don’t mean in a bad way what will work for me? What can I do? Something good out of bouncin would think, what does the company need? It needs a hit. It needs this. It needs to I have to grow this dancer. I have to find something for this occasion. We have to honor Stravinsky. That’s what we have to do. We have to honor Ravel. We have to honor Tchaikovsky. Those were big ideas. Those were not Jerry’s ideas. Here’s one more person. Hit him. It hit him.

Speaker And you think that that was born of a certain kind of security and insecurity, security and security, knowing you could do all of this vast sea.

Speaker Balancing for me is an overwhelming creative genius. It’s like asking how could Mozart do it? Well, Mozart could do anything given his time. He did do anything. We don’t know most of Mozart.

Speaker What he did came from commissions. And in a sense, you know, somebody said, hey, I’ll give you X amount of money for six quartets. Oh, OK. I know. And to a large extent, Balanchine operated that way, too. Sometimes it was his sense of what the company needed that commissioned him to do something.

Speaker You know, Jerry was looking for ways to express himself. Balanchine never expressed himself in his life, except that everything he ever did was an expression of himself. But he was everything. He incorporated life the way Shakespeare does, the way Mozart did, the way Verdi did. You know that Jerry is not that kind of creator.

Speaker What what would you say were the defining qualities of his pieces? I mean, in general now I’m not talking about themes. I’m talking about things like the use of the vernacular or theatricality, things like that, that you find Jerry’s values. What do I want to answer that?

Speaker I’m not going to make a stab at that. OK, um.

Speaker By your observation, how would you say Jerry and Balanchine used dancers differently?

Speaker Balanchine, who was also remember the chief teacher and coach Balanchine, saw something in a dancer who might have been 16 or 15 or 17 or 30 and wanted to bring it out and wanted to bring it out so that he could use it. But it wasn’t for selfish reasons, he understood every dancer, when you read the dancers accounts, say he saw things in me that I didn’t know were there. He found them. He encouraged them. He released them. Gerri was interested in Dance’s for what they could do for him in a different way. Now, he was a brilliant, if not spotting the newest, youngest talent at catching it at the crucial moment. And I don’t want to use the word exploit, which has a negative quality, but helping it reveal itself. The classic example is what he did for Chronicles in the in the Four Seasons. Everyone knew Karen Nichols was going to be a major dancer. Nobody had technique like that. But in the spring section of Four Seasons, he revealed a dancer. And in one performance opening night, a star was born and he was able to do that over and over. He had a sympathy for a certain kind of dancer, and he encouraged them and he used them. And even now we can see certain dancers at City Ballet who we can identify. If we’re looking as Robin’s dancers, they are never going to look as good. And Balanchine, they don’t have the technique. And if they have the musicality, it’s a kind of different musicality. But they’re wonderful for robins. Now, there are, of course, dancers who straddle that, like Patricia McBride, she could dance anything and he adored her and Balanchine, although I think Robbins loved her more, although Balanchine made such great roles on her, Pharrell was Balanchine’s. I think Jerry was very cautious about using Suzanne. What did he have her and Goldberg, as I remember. And then later he made in G major on her and in memory of. But it wasn’t that she was so much off limits. I’m not even sure she was a Robbins dancer in that sense. She was a classical dancer. You know, primarily that I think Jerry looked for more obvious, dramatic. Not that Farrell wasn’t dramatic. I mean, her dancing was more dramatic than anyone’s has ever been, but she didn’t act on stage. There was always an element of acting. I think injuries work there very frequently was.

Speaker I think dances for Jerry.

Speaker Were his material and he wanted what he wanted from them, and I don’t think it was that interested in them as themselves, not that he didn’t have fondness or respect for a bunch of dancers because he clearly did. But he was always interested in one thing how will my ballet look tomorrow night? That’s what it was. And Balanchine was interested in that, of course, but he was interested in everything else to the health of the company. What we needed next, what this dancer was facing with this dancer could know in the same way that Balanchine would modify steps for the needs of specific dancers, either when they came into a role or when they were in some way hurt or hampered. Robbins didn’t want to modify anything. He wanted what he had done. It wasn’t going to change. That was it, and if you couldn’t do it tough, you know, so dancers were constantly being injured and whatever, or he incurred their their displeasure. They incurred his displeasure.

Speaker Did you find generally that when you look at the repertoire in New York City Ballet, that the look of a Balanchine is different than the look of a Robbins’ ballet? I mean, they were would you say that one was more or less involved in the look of how things were on the stage?

Speaker Look, by which I mean physical production.

Speaker Gerry was certainly concerned, the physical look of the productions of his ballets and a lot of them look good. Sometimes he makes errors, but everybody makes errors.

Speaker Bouncin has a bad rep because for so many years, people associated him with black and white modernism. But of course, even during all that period, he was making colorful works with a lot of physical stuff, you know, that was very, very effective as ORFEUS. Or the big bang is the big story ballets, obviously, obviously, I don’t think Balanchine was primarily interested that Lincoln Kirstein was the one who was obsessed with art. Balanchine was obsessed with music. So that was a difference, but that doesn’t mean bouncin ignored the look of the stage. I just don’t think it was crucial to him in the same way. Jerry, I’m trying to think back. You know, there’s the earnestness of the Four Seasons. Well, that’s partly it’s a reflection of the period of the music, you know, Rossini Opera. That’s what it looked like in the 19th century. There’s a good reason for that.

Speaker Whether it helps the ballet or not is another story. What other ballets can we think of from that period, the background for Engie Major is pleasing. You know, it’s sort of Riviera Beach blue and white. It’s charming. I don’t think it helps the ballet particularly.

Speaker I just had a sense and I don’t know if it’s true or not, that Jerry was much more particular about the look of his pieces, for example, lighting than Balanchine, and you would sort of give someone a task and let them do it to a certain extent.

Speaker But one of the problems with lighting with Balanchine was that his sight changed. So the lighting changed as he responded to it. But I think that’s probably true because Balanchine knew that his ballets were there and they were going to be shown everywhere for a long time and he could only control what he could control. And then he wanted to get onto the next thing. Robbins wanted to control everything all the time. That is the analogy that we recognize in his work as well as in his person. You know, he held on to everything and he needed control or the sense of control. So certainly he would want to control the lighting, the costumes, the sets, as well as the music, the steps, et cetera. Whether it was always to good effect, I don’t know. I don’t think his taste was infallible. And I think it was partly it was partly a problem because of this needed to appear to himself or perhaps to others as being up to date. Okura he was going to do it because it was coming. It was new. He was going to catch on and go for the ride, whether it was in a watermill or.

Speaker Glass pieces or anything else.

Speaker Not counting the four seasons that you’ve already spoken about, what would you say is if you can think of one of the most underrated Robbins ballad?

Speaker How about the most overrated? I know that that would be an easy question. Well, but you don’t know that if I give a response that what I said before will still be in the show. So maybe I have to mention it again.

Speaker Yeah, but if you could just talk about a ballet, which you think is underrated, I want to say I understand.

Speaker Let me think if I can think of one. I think they’re all overrated.

Speaker Or you could say in addition to the Four Seasons or whatever color you. Well, you have to I think I’ve heard you talk about another bad well mentioned that maybe remind us.

Speaker Oh, well, that’s fun. And a swing that I’m not saying that I think it was.

Speaker Now, let me put it to me and I can get into it, I’ll find a way and I mean, we’ve talked about the fact that the war choreography that we see, the better choreographer Jerry Robbins is. Yeah, I know how to get there, OK?

Speaker You know, there are bowls of cherries that are maybe underrated as opposed to quite a number that I feel are overrated, apart from the Four Seasons, which I think is a very brilliantly put together ballet. I was very struck when the city ballet brought back piano pieces to Tchaikovsky, piano music. And what struck me was that when it premiered, it really looked sort of second level fusi. Parts of it were dull. It was pleasing in its way, but it didn’t seem to be very special when it came back years and years later, in the midst of so many other new ballets that City Ballet had to put on and was putting on in this period, it looked like a masterpiece. Now, I don’t know if that’s a compliment to it or not. There are still parts of it that are better than other parts. The duets are wonderful. The the sort of ho ho ho peasant stuff looks like pastiche and is pastiche and isn’t very exciting, but it’s very well put together and your attention is held, which is more than you can say for a lot of the exercises that go for ballets at City Ballet. You know, when something original is happening, you get it. When these Romanski ballets started to appear, everyone got it. In one minute. There’s a real voice here.

Speaker And when you see something like piano pieces, which is certainly not Major Robbins, and you separate what’s best in it from what’s not best in it, you see, yeah, this guy really knows what he’s doing and he’s got something to tell us here. The same is true of something like in the night, which originally seemed to me, you know, still more dances of the gathering after dances, the gathering and other dances or whatever. They’re all the same, you know, skylight, sky night. Starlite lifts, lifts, lifts, romance, romance, romance. But when you look at it today in the cold light of dawn, it’s very well put together. It’s a highly professional job and audiences enjoy it. So. Hey, Harar.

Speaker What would you say is Jerry’s greatest contribution to the New York City Ballet?

Speaker I think Bouncin had it exactly right. He made hits and that was crucial. That’s not to put it down. You know, no ballet company is going to survive without audience pleasers. Bouncin made lots of them, and Robbins made lots of them. And I think it was very healthy for the dancers and still is to be dancing in a different style, in different moods from Balanchine’s.

Speaker The problem now is whether these new styles they’re dancing are going to damage their ability to dance Balanchine. That’s the number one question at the New York City Ballet. And as you know, I think as we all know, there’s a lot of contention about that. And it varies. You know, I happen to think that in the last year or so, it’s been getting better after years of not being getting better and not getting better. But that’s going to come and go.

Speaker There’s no question about that. There’s no question but that Robbins’ contribution to City Ballet was important and is still important. How important? I don’t know. I think there are half a dozen ballets that the audience will go on enjoying and liking, and that can always be programmed with confidence.