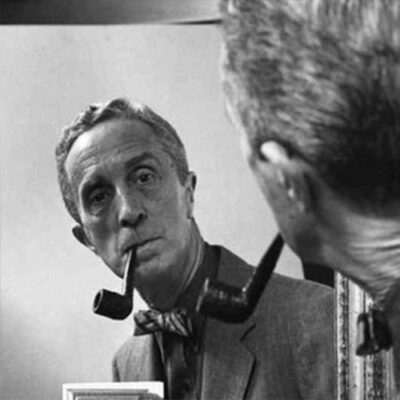

Speaker Very first impression of Norman Rockwell, if he can remember what you see, I don’t remember what my first impression of of him was because he was so pervasive throughout the world. When I was a kid in Australia, when I saw illustrations by Rockwell, because when I saw the Saturday Evening Post and I mean, I had no. I don’t remember having any doubt when I saw Rockwell’s depictions of middle class Small-Town life in America. That was what America was really, really like. And he had that extraordinary kind of ability to carry conviction about the documentary truth of his images. I think that was one of the reasons why he was such a universally popular figure.

Speaker What made it so convincing, the technique?

Speaker Well, of course, the technique I don’t know too much about. Because, you see, the thing about Rockwells is that they are always done for reproduction. They’re not they’re not made in order to be seen as freestanding pictures, although people do collect them as they have now. I don’t think it was so much the technique. I think it was the profusion of detail, the orchestration of that detail, you know, the organization of the narrative as being very, very coherent indeed. You know, you got it instantly in the way that you get things when you see them happening in front of you. And this is a not inconsiderable gift. I mean, people think that it’s perhaps a banal gift, but actually it requires a great deal of organization and of making epitome of experience and of making prototypes and all that kind of stuff, you know, boiling it down.

Speaker In other words, he was a storyteller. Right, Jack? All right. So far. Yeah. OK. All right. All right. He was a storyteller.

Speaker Oh, yeah. He was a storyteller. And he was a very good storyteller and a very concise and effective. So you didn’t work through allegory. You didn’t work through any of the means that had been available to, say, history pages in America before he gave you the impression that he was giving you life as it was lived. But of course, the life as it is lived is a tremendously highly edited and very much worked on version of the chaos that actually surrounds us in search of inspiration, even surrounded him.

Speaker Yeah, somebody said he ordered experience more than most art.

Speaker Well, he did. That’s what I do, of course. I order experienced playwrights do that. Novelists and narrative artists in particular. Do they have to? Because otherwise, you know, the results have become incoherent. I mean, you remember that famous image of the little black girl being taken into a previously segregated school by some U.S. marshals, which is one of the most powerful political images produced by an American in the 1960s.

Speaker I think a photo, a photograph of the same scheme would have had nothing like the kind of iconic compression and apparent straightforwardness of that little girl in the white dress. Now was a very, very controlled and tremendously controlled, but, you know, that’s what a good illustrator or for that matter, a good narrative artist does. You know, he or she controls the input. And he was a master of that also. He was great, you know, sort of inventing types, you know, recognizable types, finding equivalence for experiences that Americans believe was somehow there in their bones. You know, I think of the you know, that ega upright looking young man in the freedom of speech picture from the from the Four Freedoms at the town meeting, you think of the of the eternal grandmothers, you think of the apple cheeked children.

Speaker Every single one of Rockwell’s characters is one which is found somehow or other in real life, but, you know, acquires a greater density through being theatrically altered.

Speaker Right. Going back to the 40s, 50s when the Saturday Evening Post was such a powerful institutions. Yeah.

Speaker Part of what it really meant, you know, for people who don’t understand the post was powerful in a way. The Post was powerful in a way that no magazine ever will be again. I mean, it had this extraordinary kind of iconic power. It had the power of forming people’s. Ideas of what they were, their ideas about the country they lived in. And it did this not in time, not always on a conscious level to do it through illustration as well. Rockwell was the main source of this. And the when we look at the Saturday papers, Saturday Evening Post covers now, we have to bear in mind that these come with a degree of assumed credibility behind them, which nobody attributes to the mass media anymore. The very few people actually do. I mean, we tend less eMESH to believe what we read in the papers. We tend or at any rate, I tend to believe less and less what you’re seeing here on the television screen. But the people were suffered much less in the 1940s and 50s from this kind of image fatigue. And so consequently, Rockwell’s work accordingly had, you know, a an enhanced, you know, a greater power. And I think probably through the middle part of day it is today. We think they’re a bit kitschy, but I think possibly people always thought they were a bit kitschy. And so consequently, that was, you know, actually why they rather liked him. A bit kitschy, but not offensively kitschy and with enough truth in them, you know, enough recognizability. Look, isn’t he like Uncle Joe? Oh, that’s what I felt like when I first went to school. Golly, I bet that kid’s feeling exactly the same sensations as I did when I hold the first catfish out of a stream. All that, you know, all that sort of reciprocity with common experience flowed through Rockwell’s work. And at the time, I might add, when there was practically no genre painting going on in the United States. I mean, the it’s been quite a long time since the credibility of the painted image was, so to speak. Taken over by the credibility of the photograph in the film. Rockwell’s part of Rockwell’s achievement was that he managed to maintain that credibility within the handmade record use image long after it had migrated into mechanical machine made images.

Speaker Right. So was he competing with the photograph?

Speaker I don’t think he was competing with the photograph. I don’t think he would have seen himself as doing that. Certainly, I don’t see him as doing that because he was you know, his images are not images that you can’t get from a photograph. They they have the deliberative assembly and the sort of submerged allegorical character of somebody who’s putting everything there for a reason. A photograph is sort of more accidental than that. And photographs which are to pose and to assemble the media to look false.

Speaker But I mean an initial viewing. Do you think a lot of people took them as a snapshot of the real America, the real surprise?

Speaker Well, they might have done. I think I think actually many people did. But I think one would have to be fairly these days. You would have to be fairly unsophisticated about the way the images work in order to see them in that way. They you know, they’re no more snapshots of something than. I don’t mean to imply kinesthetic comparison, but they no more snapshots of something. Say, you know, a crucifixion by Tintoretto is a snapshot of a scene on this hill in the Middle East.

Speaker But he was able to because because of that particular technique, because of his, you know, extremely sophisticated powers of making realest images, he was able to invest these things with a credibility which they’re slightly kitschy idealism needed in order to put itself across. I mean, there was a great remark made by somebody I forget who in the 17th century that Pusa painted people not as they are, but as they ought to be. And the and in a weird way, that is in a weird American way.

Speaker That’s also true of Norman Rockwell.

Speaker Did he help create an American identity like a nation of immigrants, a unifying vision?

Speaker I think he had a very powerful kind of unifying effect, at least on the readers of the readers and the lookers of the magazines that he illustrated for the he was able to present an America which was quite strong, popular images, snot, rah rah, tubthumping ones that were ones that came sort of that got under your skin of certain ideas of American mutuality, American idealism, American virtue, above all.

Speaker I mean, even to talk in these terms these days is sort of nostalgic. And of course, it is nostalgic. And but the thing is that the idea of a completely virtuous republic has always been a somewhat nostalgic idea. It harks back to an original Puritan promise, the idea that America ought to be the, you know, the community within the. On the Hill and, you know, in a way, it’s a it’s an America’s never completely exhausted, but which is always surging up in American dreams. And Rockwell’s paintings both road and impelled that search as art.

Speaker Can we compare him at all to the role that television plays or at least has played?

Speaker I think there is a certain comparison to be made.

Speaker I’m sure the other questions are sorry. Yes, I think the.

Speaker He he didn’t have the.

Speaker His work didn’t have the coercive power that television has. People speak of television as being a unifying factor in American life. And so it is in the sense that it’s the menu which you can’t deviate from and everybody has to eat.

Speaker But he did.

Speaker I think his sentimentality, his kind of relentless belief in a kinder, gentler America against all the eventual OB’s had the same kind of effect upon his audience as, say, the sentimentality of something like The Cosby Show, for instance, does present day audience. He had a. Yeah. This is not to say that it was bad or anything like that.

Speaker Of course it was escapist. But most art is, in fact, escapist. I think to some extent, given the circumstances we live under, it’s not a bad idea for some out to be escapist.

Speaker But he, um, he was able to present Americans with very attractive, very convincing images of what they were, what they they ought to be.

Speaker You know, as though he was doing the the idealising for them. And he was doing this quite unconsciously. And it’s not as though he was a man with a program or anything like that.

Speaker I don’t believe that any editor ever sat down with him and said, all right, now, Mr. Rockwell, I want you to go and make Americans more patriotic or make Americans better or make them more chaste. Give them more regard for their children.

Speaker And yet, you see, when you know, when you look at the world, which is created by Rockwell’s pictures, your sense on the one hand that it’s much more real safe on the world, that that is created by Main Street in Disney World. It has a lot of documentary truth in it. But at the same time, this idea of an America in which eternally spry grandmothers with red cheeks are forever putting turkeys on the table and not long ago being firmed up, do you know, was incontinent vegetables in some wretched old folks home in Florida?

Speaker You know that. You know, you have the feeling that America actually has gone and they all have very largely gone. And, you know, here are these kids who never do anything worse than Stephen Harper. You know, they’re not snorting crack behind the serving crack in an alley way and then they’re not doing any of those things. People, and particularly Americans, yearn for such images of themselves. But you sense that it’s not a world that’s really with us anymore. I mean, nobody would call Rockwell a documentarian except that he documented dreams. He documented people’s ideas. You documented the course of people’s ideas about, you know, what society should be like. He wasn’t painting the actual society itself. And what he was painting was ideas about what the feelings about what that society should manifest and what should be in it.

Speaker And even at the height of his success, the 40s, 50s, that world didn’t exactly so strange.

Speaker Well, I mean, no ideal worlds exactly exist. You know, you can the there’s no genre painter. And that’s what he was. It was a genre painter who could never be expected to tell the entire truth about it. Society genre painting works within conventions as well. It did in Holland in the 17th century. And the. But the important thing about him, I think, was the not the aesthetic beauty of his pictures, because I don’t think actually all that many of them are all that beautiful. They tend to be a bit too tied down in the quotidian detail to to really move you to aesthetic rapture’s whatever that might mean. But it was a sense of being grounded in reality that, you know, the gratified people and the and it still continues to even though we know the reality is something of a fiction.

Speaker You mentioned Sean replanning, does Rockwell come out of artistic tradition? I mean, can we place him?

Speaker Oh, yes. Yes, he comes, you know. I mean, he comes out of it when he comes out. Is an extremely strong American tradition of journalistic illustration, combined with John reporting. And the you see, his success would not have been possible except for certain technical developments such as color printing. You know, Rockwell in black and white would not be Rockwell the yellow, but high fidelity mass.

Speaker Rapid color printing was what made him. And The Saturday Evening Post. And I look at all the rest of the possible and the the but he rises just at the moment that Americans and perhaps the world audience still wants painted, drawn. In other words, made effigies of daily life rather than simply photographed ones. You know, there is this desire for an artist’s interpretation of a scene or an idea. This is gone now. I mean, we have editorial cartooning in the United States and most of which is completely toothless. But there’s almost no illustration outside the boundaries of advertising, which is used for communication of facts and ideas about everyday life for journalistic purposes. Rockwell was the last you know, he was one of the first and also one of the last great exponents of this. And he you know, he belongs both in a technological matrix and in a matrix of style.

Speaker The style tries to be style as auteur. You’re not conscious of a particular sort of. Rockwell signature.

Speaker It’s not as though you think he has a particular kind of handwriting in the way that you can tell a Jackson Pollock squiggle from somebody else’s squiggle. He always sought transparency. But the style had to do really with beliefs and ideas and types. And there you can tell him every time. I mean, people have tried to people constantly tried to sort of imitate or rival Rockwell’s narrative manners and mannerisms, but it always came out not quite as good.

Speaker So that’s what set him apart from other illustrate. I think that’s what set him apart from other illustrators.

Speaker He his skill, his evident sincerity. See, people sometimes say that sincerity is not a criterion in judging the visual arts.

Speaker I think that’s probably true. But nevertheless, I think it is sometimes at least possible to tell when it’s there. I don’t mean that. You know, you have to be a religious person in order to paint a religious picture. I mean, history shows us that there’s absolutely no true. Some of the most moving crucifixions have been painted by absolute rakes and constantly agnostics. But the party doesn’t enter into it. But he he there is a kind of. Seamless link between the America that he was painting that Americans like so much. And I think his own feelings about America. I think he was well aware towards the end of his life that, you know, it was going it had gone. He was once asked to paint a portrait of Spiro Agnew, and he regarded that as a perfectly awful chore. But he. He was looking back from the vantage point of the 1950s and even early America earlier, America did not see America basically based on the 1920s and the the, um. He was looking back on it from the way that a Silver Age Roman might look back upon the the noble virtue, the noble Republican virtues of the primitive Republican virtues of early road from a much more complicated and despotic and glitzy age. And so, you know, this is the sort of the source of his nostalgia as a kind of belief in American virtue, in American mutuality, commonality and all the rest of it. Always, when these things are painted or represented, the subtext is always that they’re slipping away. I mean, people started talking about the loss of American innocence almost as soon as the watch got here. The first real expression of nostalgia for a better now vanished America is in a long, rhapsodic piece of writing by a Puritan named Samuel Sewell where he’s talking about. I believe, if I’m not mistaken, somewhere around about 16, 17, he was already lamenting an America which was purer, more noble and more in tune. You know, there was there was more of a tune up between man and God that happened in the last 30 years. So this is a continue. Yeah, this is a continuous American trope. And Rock and Rockwell was but not a tool, the first person to get onto scene. He didn’t get onto it. It was in his bones. You know, to be an American is to be nostalgic because you were condemned to perpetual disappointment because you were supposed to start out the city on a hill in a life until the world. It’s hard to imagine somebody as completely ironical as, you know, these representations of day, you know, daily civic life as Rockwell was arising, for instance, in England, which is a much more skeptical place, still less in Australia where I come from, where, you know, we began as convicts and so had nowhere to go but up again to disappoint our own expectations because we didn’t have any. Yeah. You know, it’s it’s. I mean, this, again, is, you know, is why he’s such a very, very, very American artist who can you know, I don’t say that he’s a very, very great artist. That’s a different question. But as somebody who was speaking through who a certain ethos spoke almost media mystically, you know, if you want to know America, you’ve got to some degree to know Rockwell as well.

Speaker You do call him an artist, though, not an illustrator.

Speaker I don’t see any different scene artist and illustrators in the same way as I don’t see any difference, you know? I mean, people used to use the word decoration as well. You know, as a disparaging term. I don’t see it as being disparaging. You know, otherwise there’s so much you’d have to rule out of court. The gift, of course, he was an artist. I mean, I don’t think he was one of the very greatest American artists that he doesn’t certainly excite me imaginatively or emotionally to the same degree as certain paintings by let’s save one of his early contemporaries like Marshman Hartley. But you’d have to say that he’s not an artist, as was the fashion a few years ago. I think it’s ridiculous. I don’t believe in these very hard and fast distinctions between harps and crafts, between artists and demonstrators and so on. They didn’t hold true in the past. I don’t see why they should be taken to hold true today.

Speaker I want to pick up just returning to the analogy between rock on television. You hear that he had the kind of depth, loss, narrative, clarity of the television screen, and you could just speak to that.

Speaker Well, he does. This is pictures do have that deathless narrative, clarity of the television image. They are not intended to be enjoyed as things covered with, you know, mud colored mud with an apprehensive texture and so on and so forth and the presence of the wife and a different size all on the surface as paintings are they are they like slides through which dreams are projected and the the. I mean, he understood the nature of mechanical reproduction extremely well. And the the. And this, of course, only made them real for the for the audience, because if you subtract from the image, all those kind of things which seem to betoken the particular artist’s hand, if you have an image which is just all icon or detail or event and no artist getting in your way and saying, hey, look, I put this bit of mud here because I like mud for certain. The then, of course, you know, it does get realer for the audience. And I think that certainly happened with with Rockwell. I mean, I’ve got to confess to a certain feeling of disappointment sometimes when I see an original Rockwell compared to the impact that the thing had on me in reproduction. Really? Why? Because they don’t stand up all that well as painted surfaces that are pretty interesting, as painted surfaces as such, but as projected images that, you know, the they can be extremely powerful.

Speaker I mean, some people do talk about the brushwork craftsmanship.

Speaker Oh, yes, they do. They’re done at a very high level of craftsmanship. It is, however, self-effacing craftsmanship.

Speaker And the.

Speaker Who did they admire? I think more than anybody else, you probably admire the Dutch tradition.

Speaker You know, with that smoothness of surface, that continuity of modelling, that feeling of the rule of control over texture and all the rest of it where, you know, the thing seems to have been breathed or or is about to swell up and become three dimensional without any agency at work by self-effacing, self-effacing technique, self-effacing technique is extremely hard to do.

Speaker I mean, if you want to do it consistently and. And he was. It is true. Very, very good at that.

Speaker What do you mean by that self-effacing brushwork?

Speaker I mean, texture is tuned down. You don’t get, you know, startling contrasts of color or tone which are placed there in order to aesthetically provoke it. It’s photographic. What can I tell you? It is photographic, except that it doesn’t look like it in the end. It does things which photography can do.

Speaker Rumor has it once more than rumor. I guess that Rockwell made statements now, now that he wished he could paint like Picasso or that he had wrapped in this caricature and the sense of style that he’d gotten into him. Do you think he could have done more?

Speaker I don’t know. I think he did quite enough as things were the. I mean, sure, he might have wished he could play it like Picasso. I don’t think he really wished he could have painted like a cancer. Maybe what he meant by that was that he wished the people thought that he was more of a virtuoso and less a sort of transparent agency for the projection of popular images. But I just don’t know.

Speaker I mean, the certainly anybody less temperamentally fitted to play like Picasso was never born. It’s really hard to imagine. But, Rockwell, to you know, to some of those erotic images of Picasso’s in the 30s, I just it’s it’s totally unimaginable.

Speaker It is ironic that this sort of dichotomy between the popularity of Rockwell’s images and the emotional power they have over many people in this distained are kind of snickering on the other hand, that goes on.

Speaker Oh, yes.

Speaker Well, I mean, look here and there in the 50s, maybe in the 60s and possibly even later, if something was popular, it was bad, full stop. You know, there was you remember that famous classification of of of like McDonald’s Mass, Carlton, Big Calcium’s and so forth. And, you know, if you like one thing and, you know, in one category, then admit that you were the essentially the enemy of whatever it was in other categories, you could not simultaneously like, say, Palestrina and Little Richard.

Speaker You couldn’t like both analytic cubism and the cartoons of Bill Malden.

Speaker All this seems to me to be much less certain today. I mean, certainly, you know, I you know, there’s a lot of intrigue, a great deal of, quote, high unquote art that I like. But it doesn’t mean that you have to, you know, spill stuff which is very good within its own kind of context. I mean, you know, look, the great. For that matter, look, the great achievement of America was not. I don’t think it’s individual. I don’t think it’s architecture. I think it probably is music. You know, the great cultural achievement of America was jazz and the the musical comedy. And the you know, there’s nothing wrong with this one would, you know, be unrealistic to treat this as though it were not so much. You can you know, you can have a civilization like this one whose primary cultural achievement is mainly in the humor in the domain of popular culture and entertainment. And the the. Which is not to say that it doesn’t produce, you know, some remarkable painting paintings by remarkable painters and great novels and so on and so forth. But the stuff that is really best that might be entertained. And I think that is probably the case with America. And it they’re not universally so. And in a culture of intelligent entertainment. Norman Rockwell is always going to have an important place. And the idea that enjoying his work in some way degrades your aesthetic responses to other and greater work. I think it’s nonsense.

Speaker Why rock one does nature or the two most the best known American visual?

Speaker They would be they would be the best known. But there’s a huge difference between them, between right between Rockwell.

Speaker And there was a huge difference between Rockwell and Disney, because Disney’s vision was a corporate vision and it was coercively you turned out to be coercively utopian in a way which rockfalls never did. Rockwell’s address to the world was always much more modest. I mean, he didn’t go around building Rockwell and he didn’t go around finding people to pour enormous sums of money into animatronic dolls based on these characters. He didn’t you know, in other words, you know, he he you know, there wasn’t that bizarre element that you have in, you know, in Disney of the construction of a literal alternative society, a kind of utopia within what can you call a utopia within civic failure that characterizes places like Disney World. No, Rockwell was just modestly affirming, certain the value of some imagery imagery which he believed correctly, he held in common with his audience.

Speaker Now, some people have done it before. I mean, you could argue that the image behind us, Main Street, Stockbridge, is a kind of Rockwell land that’s become an icon.

Speaker Of course, there’s this continuous feedback between, quote, reality and, quote, imagery. The places re-form themselves in terms of images that have been made of them in the past. And they they I mean, half of New England’s begins to look that way to me after a while. The. There is always that give and take that ebb and flow between supposedly between reality and icon. It just it just keeps on going. And particularly in America, where there’s so much money to be made of these transactions.

Speaker What about I mean, talk about freedom from want, you know, that famous Thanksgiving.

Speaker Oh, yes. Painting. That’s right. I mean, if there’s any Rockwell painting, I suppose that’s an icon.

Speaker That’s that freedom from want would have to be the most famous painting that Rockwell ever did. Famous famous illustration that he ever did. I’ve never seen it as a painting of any obscenities administration. And it is so because it sums up so succinctly those strands in Rockwell that one thinks of as being quintessentially Rockwell and quintessentially American. First of all, there’s the imagery of nurture, the that spry clearly quite still quite strong grandmother with that enormous platter know with the with the giant turkey on it, about to set it on the table without any particular sense of strange. He’s been doing this once a year or that life. There is the desire for continuity which is expressed in the generations of the family. Most important is the feeling that it projects that what you’re getting is a kind of virtuous abundance rather than luxury. Now, the idea of luxury as understood by Americans in the 1980s, that is to save really over the top super consumption is totally alien to rockfalls world. What Rockwell is talking about or painting about this picture is a direct link which has never been eroded back to the original Puritans. The Puritans come to America not in the expectation of getting hugely rich, but getting free, free, admittedly, to persecute others, but free all the same. On the one hand, that on the other hand, coming into a place of natural abundance, which is the reward given to you by God for consistent and virtuous work during the rest of the year. And that’s what that picture is really about. It’s you know, it’s not about American excess. It’s not about the America of Trump Towers or anything like that. But not that the Trump Tower existed when he did it. You know, it’s not about dinner at Le Cirque. It’s about people under living under modest circumstances, getting the fullness of their heart’s desire, but not in an ostentatious way. And so, of course, people just react to that like Pavlov’s dogs. How could they not? It’s so built into the very structure of America’s own mythology about himself. He had quite an ability for hitting these veterans.

Speaker Now there is a purity apple white, the height of simplicity, the white like the the absence of interior decoration, the plainness of the furniture.

Speaker Plainness of the light, the way it falls. Everything has to do with a kind of calm explicitness, this regional drama in the picture. You know, it’s not you know, it doesn’t have courage. You know, if you could contrast sight of a Barock picture of suffering a mass suicide, I can imagine that, you know, there are no big lights and shadows. Everything is plain, everything’s explicit, everything is candid. And that’s because it’s all under the eye of the world. And overdraft.

Speaker And he knew that we wanted to think of ourselves as one.

Speaker He knew that he wanted you to think of yourselves as that. But as I say, he was being mediumistic rather than manipulative. The the he you know, the really great popular artist is not the person who says, I’m gonna figure out what people want and then I’m going to do it. It is the person who wants what people want. Quite unselfconsciously. This was the secret of the secret of Dickens’s success. I don’t say it is genius, but certainly it his success. And on a more modest level, I think it’s also true of Rockwell. If, you know, if Rockwell had ever tried to sit down and figure out what the audience for his images wanted, then he might very well not have succeeded. But he didn’t need to. He just did it, you know, on autopilot because he wanted what they wanted.

Speaker What about the 60s and Rockwell, his work? Certainly, I want to change the 60s. Something in some somewhere.

Speaker Well, no. Listen, Rockwell was, after all, not insensible to what was going on in this country. And it’s inevitable that, you know, you’d get some references coming up to contemporary history as it was unfolding in the 60s. You know, I’m rough on you as well as anybody else that, you know, Small-Town America was beginning to come apart, that there was a very different spirit abroad in the land of that which should, you know, inhabit it. In his teens and 20s, which, after all, was the formative period. He and I think by then he also although since I didn’t know him personally, I you know, obviously I kind of say but I have the impression that by then he was, you know, very well aware of his position as a kind of mediator of American dreams. And he probably thought it would have been remiss not to have made some references, however veiled, to have a sophon to what was going on in the 1960s. Plus, of course, he was an illustrator working to commission for magazines. And so somebody rings up and says, okay, we want something we’re doing. We’re doing this big story on school desegregation. You know what?

Speaker Yeah. What do you think was the greatest period of his greatest work in the 40s, 50s?

Speaker I think the 40s. 50S, yes, I think so. It’s the one in which he really found his feet in which these these sort of national icons, as it were, poured out of him. See? He’s a lungfish because other artists probably know less skilled than Rockwell tried or were people tried to get them in other countries to perform the same kind of unifying functions. And his work, when you look at it, does not, after all, all that far from the bases of Soviet socialist realism. And, you know, it has quite a few of the same mutatis mutandis. It has quite a few of the same beliefs, too. And it. And yet, I don’t think there’s any other artist in the world whose work is, you know, seen within his own society with the same continuous affection as as Rockwells. And I think affection is the key word. You go to him like somebody’s going to have a fond and friendly and utterly benign uncle or out. You don’t go along expecting Blakelock revelations or, you know, Beethoven like Ecstasy’s. But the people have always gone to him out of a desire to know something about what being an American was supposedly all about. No, no. I’ll just give you the whole truth on that. Rockwell certainly didn’t. And yet, nevertheless, you know, like a sort of honest Broza, people believed in the. You know, really gave you a pound of this. It really was 16 ounces anyway.

Speaker OK. So when we talked about the history of 20th century American art, I mean, is there any can we put Rockwell in any context? Can we compare him in any way to. I don’t know why. Of anybody.

Speaker So, yeah, I mean, I think.

Speaker Well, look, I think that Rockwells place in the history of American media is quite an important one. Probably more important than his place in the history of American art. Although that said, I think probably American demonstration should play more of a role in the history of American art. I mean by illustration anything from comic strips which are, after all, a great and remarkable American art form through to illustrators like Rockwell. The. Yes, there are similarities to Wyeth in that he was you know, but both artists were deeply concerned with, you know, I suppose they are deeply concerned with the case of feminism. But, you know, there is similitude getting, you know, a perfect illusion there on the canvas. But there are very great differences. The Rockwell is without the strain of melancholy that you get in Rockwell’s.

Speaker Vision is inherently social, and it’s about a lot of people living together in the same social space. Whereas what’s very much is not, it’s about loners and small communities and the.

Speaker Sorry, that’s. Let me start that again.

Speaker You can say the Brockwell and why I have something in common, because they’re both very tight focus realists, but that doesn’t take into account the great differences between them as temperaments and as artists. And Rockwool is always painting fairly richly populated communities, you know, in social situations that involve a lot of people, you know, that reach out and have clear kind of allegorical references to the, you know, to larger spheres. And he’s totally without that kind of melancholy verging on paranoia that you get in. And while wealth is very much a painter of loners, he’s very much a painter of people who are at the margins of what Rockwell would have regarded as the core of America, namely Small-Town life. You know, he’s painting a rather weird fish, you know, standing on butcher hooks in cellars in remote parts of Pennsylvania, whereas Rockwells out on the village green, the you know, there are big differences between and the the.

Speaker But the fundamental and a lot add that, I think.

Speaker A clue to why they’re both so popular. Also has to do with the ease with which they work. Transmits itself through mass media, through reproduction. But Rockwell was upfront plaiting for reproduction and wife. Strange to say, actually was not. And this, I think, also affects the sort of character and tone and address of their work.

Speaker The thing is that there isn’t a wide range of American genre painters, American painters of life as it’s being lived with whom you can compare. Rockwell, it’s just not not a form of painting which has ever been.

Speaker All that popular in America in the 20th century. It was in the 19th century. I think you began to find ancestors to Rockford. You’re going to find them in the you know, in the 19th century genre, painters like William, Sidney, Mount. And, you know, there was a whole kind of academy academies where there was certainly this sort of whole lingo, which expression in the 19th century of family values. Yes. Family closeness. You know, people doing things together on farms. People, you know, kids, particularly the allegorical kid, you know, was the as the image of young America that, you know, I mean, this really begins in the early 19th century and it reaches a you know, it’s best aesthetically, I think, most convincing expression in that in winds like Herbert’s paintings of small boys and girls going about their business of learning and doing things about this issue. This is young Americans. This is young America. Feel like it’s try to go. You know, you’re asked to believe that and you do believe it. And the the the antecedents of Rockwell lie in that kind of genre. And then, of course, they they kind of drop off the screen.

Speaker Mercifully, I think a lot of cases, one gets very tired of all those pictures of hrough become children, you know, gathering blueberries, skinning the pooh or whittling sticks or what do you think the horrible little beast. But the the.

Speaker They are reborn in full feather in in Rockwell, but in a less entirely rural kind of context. That’s where his American roots lie.

Speaker I was going to ask about he children extensively and even then during the war.

Speaker Oh yes. Well I guess was going off. Yeah. I was like young, young.

Speaker I know he did a great deal with the image of the child or the adolescent has potential America. But Americans love to see themselves and their history depicted as being fundamentally innocent, which is, of course, a giant lie. But nevertheless, it’s a lie told in the service of, you know, sort of idea of national identity, which is still very powerful and is believed by a great many people in its enormous loss of American innocence. Hadn’t Rockwell. Certainly, I think certainly believed in himself. And he wanted to preserve.

Speaker How about. Modern art or postmodern? I should say, is there anybody we can compare to Rafa?

Speaker I think absolutely nobody at all. I don’t think there is any artist at work today. Not at day rate in the you know, the sort of gallery, Matrixx Museum matrix, who has any significant similarities to Rockwell whatsoever. What do you think that is? Because nobody either people don’t want to do that kind of arduous, slightly sentimental sentimental realism. Well, I just don’t feel that it has any reality for them anymore. As art makers, it seems it seems like. And indeed, it is a vanished era. You know, you see Rockwell as the emissary of a time which has completely gone. This doesn’t prevent you from feeling pleasure and nostalgia and cosiness of warmth in looking at Rockwell’s pictures. But I don’t think that there’s anybody around today who really believes that he can be an absolutely straight face, do those kind of pictures anymore.

Speaker So painters, photographers working today with television, who killed television, killed that kind of thing.

Speaker Television ruined the game.

Speaker And it turned because it provided people with a take on quotidian reality around them, which was much more grainy, gritty documentary, vulgar, flashy. All the rest of it. You know, you didn’t have to wait for the illustration in the Saturday Evening Post. You’ve got it that night to problem for a painter who wishes to be a documenter of his or her times.

Speaker So painters, artists working today would have a look at daily American life and add irony, Suzanne. Oh, yes.

Speaker I think so. Yes, I think so large that sort of uncomplicated, though by no means simple minded take on American characteristics, American virtues, American aspirations isn’t really available to intelligent artists anymore. I don’t think. We miss it. It’s one of the reasons, of course, for the popularity of Spielberg. It’s one of the reasons why Spielberg is so crazy about Norman Rockwell in the sensibility that goes into a film like Saving Private Ryan is actually very close to property that has local gore and blood it.

Speaker I wouldn’t. Why do you put. Saving Private Ryan?

Speaker Saving probably because it is a it’s very much a celebration of an idea of natural American virtue triumphing over impossible odds. And I mean, it doesn’t, you know, far more dreadful and documented and realistic kind of way. I mean, if you compare the movie like private round with one like the longest day. It’s just astonishing what a gulf lies between them.

Speaker But, you know, the the idea that at the same time the. Kind of sensibility that runs through Private Ryan is much closer. In my opinion, to Norman Rockwell.

Speaker There it is, say to the Stanley Kubrick of of President Stanley Kubrick’s movie set in Vietnam.

Speaker Apocalypse Now. Ask Koppel a.

Speaker I think about. Yeah. Okay, I’ll say that again.

Speaker But the spirit that inhabits a movie like Private Ryan is a lot closer, in my opinion, to Norman Rockwell than it is to your earlier war movies like Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Different World.

Speaker And Spielberg himself draws them and he’s drawn. So they took specific images from Rockwell for like Empire of the Sun.

Speaker Yes. Yeah. Again, running to trial and E.T. will be the.

Speaker Spielberg, like Rockwell. Oh, they want a much higher, you know, a much bigger level of sort of budget and cost of all the rest of it, understands that there are certain things that Americans never wish to see screaming about themselves. And one of these things with the primacy of childhood.

Speaker How does it Rothwell’s gonna be seen in the future?

Speaker I don’t have the slightest idea. Whenever anybody asks me anything about anything is gonna look like or happen in the future. I always shut off because I know one is always wrong in prediction. I think he’s got this sort of fairly permanent place. I can’t imagine people suddenly losing interest in Rockwall anymore than I can imagine people suddenly losing interest in John Philip Sousa. That’s it. It you know. And even when, as I think is the case now, he has ceased to be sort of documentary evidence of what America is like. He’s always going to be a rich mine of evidence about what America thought it was like. And so have anybody who’s at all interested in the past and who is not is always going to be interested to some degree in Rockwell and just enjoy the images from what they are. Yeah, I mean, nobody in his right mind would try and place him on the left with Rembrandt up to self or Picasso. But, you know, there were all sorts of graves and not everything that is interesting is on the upper slopes of Parnassus.

Speaker I mean, he’s not in any of major museums. No, I don’t believe.

Speaker Oh, is not. He may. Well, he may be. I don’t know. But this is this is the fruit of the art of the extreme, you know, sort of prejudice that the the the post of, you know, the rise of abstraction as the American form produced and the, you know, in museums in the post-war years. I mean, it seems to me that he should actually be in any museum whose collection wants to give an account of the culture that we know, the way in which our culture is traversed and negotiated, things that went on in the last hundred years. I really, particularly in America, it surprises me. It would surprise me if there wasn’t a rockwool in the Whitney Museum. But if there isn’t, there should be the see if one is allowed. You know, if the Museum of Modern Art feels a part of its mission to collect propaganda posters of it devoted to. Constructivist Russian constructivism. And I’m sorry if the museum in Boston feels it’s part of its purview to collect posters which reflect the ideology, let’s say, of early Leninism, constructivist posters from Russia and so forth. Why should it not also collect other icons which are intended to reflect and to glorify capitalist realism, of which Rockwell is undoubtedly one? I think what a sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. Sooner or later, though, he’ll become collectable by all museums as he was seen from view and as that old, you know, sort of binary attitude that, you know, if you liked Rockwell’s work, then you couldn’t possibly like it or dig or have anything serious to do with that Pollock or Rothko. In the end, it all ends up sort of with different points of what is essentially the same matrix. And I think one can say this without, you know, saying that the best of of Norman Rockwell is as good as the best of Pollock. I mean, you know, it’s apples and oranges anyway. I’ve no doubt which has the highest rate of achievement. Pollock. But that doesn’t mean that Rockwell doesn’t belong in any kind. You know, he was a sort of a central evidence in, you know, in any attempt to understand how visual image has affected Americans.

Speaker This is work of monetary value today.

Speaker I don’t have the slightest idea. I imagine it’s probably very expensive. It probably is. I mean, God knows everything else is. I don’t know. That’s a question about those collected. Yeah, sure. It has military value. So does sales from Walt Disney films.

Speaker What about his popularity abroad? We started off talking about that. But I mean, wow. Why is he.

Speaker Well, he’s neat. He never was and never will be as popular abroad as he is in America because America is the. Was a subject. And it was also it also contained the audience to which he addressed his work. But the the I mean, I said I certainly saw Rockwells when I was a kid in Australia, but they weren’t part of my statutory fodder in the same way that they I guess they would have been for a similar twelve year old in 1951 in America.

Speaker Now, it’s really part of daily life, right? Yeah.

Speaker Yeah, it was part of daily life, like television. It they just they were inescapable. You didn’t know that you were looking at a painting by somebody you thought you were looking at America.

Speaker So I mean, if you were speaking to Norman Rockwell eminent, we had a continuous Fungai hours publicly said he was an illustrator, but privately said, you know, he wanted respect as an artist. You would say you are what worked.

Speaker What I would say. I don’t want to get into this one because I don’t, you know, see that there’s a hard and fast distinction between illustrators and artists. It seems that when people use a lot of people use the word illustrator, they mean a figurative art history and I think is rather vulgar. But I don’t go in for that kind of stuff. I mean, I think there are now, of course, he’s an illustrator and the strict technical sense in that, you know, his work 99 times out of 100 was intended to illustrate texts, that is to say, to give a visual epitome of what a text printed in a magazine was about, that it’s inspiration, therefore, was to, you know, to some degree. Secondly, it’s not completely autonomous. It’s tied to the text. It it’s also under certain constraints of a technical nature through having to be mass reproduced. Yes. Or all of these things are characteristic of illustration. The I’ve always thought it was funny that, you know, when when people did that in. In Elumelu, in missiles and hymnals in the 14th century, it was referred to as illumination rather than illustration. But the see, there’s an old and honorable and close dense relationship between the word and the image and the images of constantly being pressed into the service of illustrating words. If this were not the case, there would be no tradition of ecclesiastical art. So the mere fact that Rockwell’s work is dependent upon texts for its existence doesn’t, in my opinion, take it down a peg. But on the other hand, you know, to compare his work in terms of how we use the word quality these days, but in terms of policy, to say great early Renaissance French manuscript illuminated like the blue Akko master, I mean, that could be silly. It’s just not that good. But it’s pretty damn good.

Speaker So Rockwell is a storyteller, a mirror as an American. He’s an American storyteller. You know, he’ll see. And that’s primarily what he is.

Speaker I mean, I don’t think that he’s got the genius of other American storytellers like Twain, but that, you know, early on, he finds a very distinctive visual vernacular, which is very American in its love of anecdotes and that side of the mouth humor in sentimentality and in its choice of imagery. And it turns out this has a big public response and he sticks by it. And the the. This means that he is not you know, I mean, his career doesn’t trace a great sort of self-critical arc of constant transformation in the way that, you know, Picasso’s or so Goya’s does. But it then perhaps even to invoke such people as, you know, in the context of Rockwool is a bit absurd. But nevertheless, it is what it is and for what it is.

Speaker There’s nothing better in America.