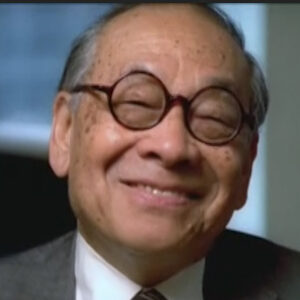

Interviewer: Bob, how do you remember Sandy Calder?

Robert Osborn: Well, it’s a large man to begin with. Karshi eight too much and drank too much wine. So it was a big fat fellow. But the great thing about him was if he was a friend, he was so generous, you can hardly believe it. And there are things that markets out there. He would bring those for a birthday party and just give them to El-Mahdi. You couldn’t believe it. Or jewelry of that huge just to hand these things over. Or I would go down there to get once I’d been down to Roxbury and out in the barn on a shelf broken wooden shelf. Watch this piece of his butt that big my cat cut out of iron. Rusty as could be. And it was actually I know now it was the first study he’d done for the whale that ended up to me to modern art in New York. This is for Bertie. I was giving out a birthday party and prescient. And I said, Sandy, could could I possibly buy that? And this the quality man, he said, well, would seventy five dollars be too much? And in those days, I wasn’t earning too much. But I got it. And it’s out in the hall. Still great drum and looking at it. Or lunch at the Museum of Modern Art. It’s here again. It’s a generous business. All the girls work near the museum. This is nineteen thirty two. Thirty three. Bottom of the depression business. And here’s making pins for Dorothy Mellon, various people down there. And Ellie was the only one who didn’t have a pan. And so he she said, well, Sandy, could you make me a pan? And so here, pretty soon he came in and handed her one of those pins and said, would ten dollars be too much? And it’s always that. However, on the other side, if he had been insulted or somebody’s done something to him that he didn’t like, he remembered that elephant boy. He remembered it right to the very end of his life. It just nobody ever got excuse if they’d if they had somehow to them. It’s very fond of Kurt Vaterland turn. And then Peter met keys and pearls.

Interviewer: How do you remember Calder? The artist?

Robert Osborn: Oh, the ingenuity, that man, the inventiveness, I keep comparing him to the Wright brothers. Think of those two fellows out there conceiving correctly. What would make a plane fly? But Upcher, Sandi’s time sculptured hours when this solid, three dimensional thing. And this fellow single handed with no precedent whatsoever of control. Suddenly, by using gravity and his engineering skills but evolve the same that moved, quivered or anything behaved like leaves forever. And I think I’ve said before, here’s a man moving out into space. Think of it compared to our own time. And this is happening. Well, as a small boy, you know the whole thing of making toys. But the inventiveness of the man, the creativity of it. But to go from a solid, three dimensional something to two, there’s a sort of thing I find when the real amazing steps in Western art.

Interviewer: How did you. Do you have. How did you see that inventiveness day to day in the man, not just in inventing the mobile?

Robert Osborn: Well, let’s see. In the household of cars here. Road is cancelled. Very strange. Including your toilet paper holder. It was like this. And he had a rather ribald quality to them, which came out every now and then. And. But almost anything he touched was given this this thing. He couldn’t help but do it. It was some innate thing, quality within him. And he put it to marvelous use.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for a second. If you were going to describe Sandy Calder’s art to someone who didn’t know him. How would you do that?

Robert Osborn: Well, first of all, I chased me highly inventive, highly inventive and very much just a lecture. The Wright Brothers invention of that aeroplane. Oh, also playful manners. And a nice thing about Sandy was he retained as few artists do a childish approach. She could get back. It changed me to performing very much away child making a picture or creating anything. But Sandy never lost that ability. And then, of course, lovely imagination to back it up.

Interviewer: Is that good? I mean, some would say, well, that he’s not a serious artist.

Robert Osborn: Of course not true, anybody? Calder’s, Sandys surely was a serious artist. Anybody who can alter a whole stream of Western culture is a serious artist. He may approach it joyfully and playfully. And you see it so clearly when you go to a museum, a large show of Calder’ss, the people are all smiling. The audience is smiling, enjoying it. And I think this case, Sandy, is moved down and life gave him pleasure that the thing was so unfailingly joyful for other people. But that course came right out of Calder, his approach to life. It was one of a pleasant shifting of these these delightful experiences.

Interviewer: Can you tell us if we don’t know about Sandy’s interest in the universe? And my question is, you drew him going out into the stars and catapulting. Tell us about your drawings of him and his interest in the universe.

Robert Osborn: Well, let’s see. I mean, I made those drawings, I think Gene Lippman asked me to do something and I drew the idea of which always impressed me and my wife. That here is this man inventing this. But in this century, as we moved out into space. But Sandy proceeded this. He began making these things that were really spatially aware and the space between different parts of a movie or all of that. And this I find such an achievement. It’s it’s hard to describe.

Interviewer: And why did you draw him launching into space houseguests?

Speaker He he really did project himself into space, just the creation of the mobile app that that whole idea of doing it. I find so remarkable that a man single hand with no precedent whatsoever. He was able to create to do this. And it changed me. He was springing himself out into space and spiraling. And here’s this enormous car. So the guy we’re living out there. I don’t know what amused meter to draw in that way because, you know, his father did the statue on the top of the down in Philadelphia. These are heavy for I’ve forgotten how many tand statue of William Pan. And when he looked at Sandy’s work, he was kind of appalled that his son, instead of being a good, solid sculptor, was doing this same thing. The father, I believe, said, well, it’s at least amusing. No comprehension of tau, apparently, really. But Sand was doing and Sandy couldn’t help but create in that fashion. You felt the genes somehow compelled him to do this. This sort of thing. And then later the stabile.

Interviewer: Is that an innovation?

Robert Osborn: The stabile, as well as certain, the fact of just using a piece of metal that thick and cutting it out. We have some examples of that. Luckily, bolting it together. I don’t think, you know, nobody done sculpture of that short. The stabile. be mentioned the name the circus.

Interviewer: Tell me if you if you were at a circus performance and why it was so special.

Robert Osborn: My whole family once went over to Lake Worth, Marg. Sandy was putting on the circus. He brought it in this great big warm trunk from Paris, where it had always been an enormous success, attracting people like Miro, people long to see Sandy Circus again, the American, young American. This playful fellow, this large man lying on the floor halfway, Louisa playing a Victrola and music to go with it. Beautiful Louisa. And the combination of this man, this mountain of a man with these little tiny figures, but that large, crudely made. But the idea always so, so clear. And he might use a spool for a head or whatever came to mind or the elephant or clearing up after the elephant with a little bit of a dustpan. This right here is this enormous man on the floor. And the thing was, Apsey contagious. People were roaring with laughter, but just sort of a shimmer of humor going over this. And very often, as with the crappies, workers would go like this. Sandy would pull a lever and fire this trapeze. And mind you, he’d figured out what would happen and the trapeze person would go. And with these little hooks would catch the partner on another crappies. It was right there, just the right moment and marveled at Tosh. But to see this this large man still playing very much like a child rolling out a little rug before the belly dancer came on or something. But as I say, you couldn’t believe the combination. It was so rare and so delightful that here all of us were sitting on some plank benches down there at Lake Wal-Mart. This man down a little bit below, below us, putting on this circus step by step and speaking in French, occasionally giving the commands of the circus. The doctor who ran the place ran the circus. And my son has said it was an experience, just really changed his life. It was that you’d never seen anything like it.

Interviewer: Let’s cut for just a moment.

Robert Osborn: Story at some point.

Interviewer: Tell me a story. An anecdote about Sandy that might show us something about his personality and himself as an artist.

Robert Osborn: Well, it’s very interesting. The old Life magazine, when they switched from using photograph on it to using a drawing cartoon. And they asked me if I would do it. And they had a long article on people with hangovers. And so I drove Man Carl expression and a nail coming out, going right straight through his head like this. Well, about a week and half two weeks later. Sandy showed up here to house some dinner party or lunch, and I’ve forgotten which. And he brought this thing where she had put together and he was he came in the door. He was wearing this nail, this tenpenny nail fastened to his head. And again, the generosity, he just handed it to me. And you can’t believe and I think will not speak about this Calder you tried to put together two pieces of. Very often different pieces of metal. And that is exactly as solid as Zord had been welded. And this if you watch Sandy work in the studio down at Roxbury and the concentration of the man was unbelievable. I think if you’d been hit with a tomato in the rare, you wouldn’t have noticed it because you would. His eyes were so intent on using that pair of pliers and taking that wire and running it perhaps through a small hole that he had drilled. But he had the capacity. I don’t know his engineer, FLOC, but not just a mechanic. True to so tight knit wire that, as I say, it was exactly the thing you began welded. And if you don’t believe it, tried to do it some time.

Interviewer: Let’s switch a little bit. I read about Sandy, having a conversation with you about color in his stabiles. Can you remember that conversation and why he was saying he was talking about whether you use what colors work red or black or whatever? Can you tell me about what his feeling about using color was in his sculpture?

Robert Osborn: Well, when Sandy was discussed with me about using color on this sculpture, because very often I felt that black and white was so effective. Sandy was said, well, I’m very fond of the three primary colors, blue, yellow rand. And he he had a very nice sigh. As you will see in some of the lithographs every once a while, you put one together for Schoenberg Land in which he was so sensitive about color that even on a flat piece of paper about that large, he did these in gosh, did these colors of, let’s say, vermillion and black up here. But then he put a yellow circle of hair and a blue one there. Marvelous size to the composition of the thing. And by Jove, those things would begin to take their place just kind of flat surface. The color would the blues would recede or red come forward. Right. And it was almost as that thing was became a more mobile printed on paper. We have one. Mobile in which one side is painted black. All of the pieces are painted black. And the other side white. And it’s lovely. Different times the day. To see that and the slightest slightest breath of air. To watch that thing begin to move this way. And as various combinations of flies here of those three white and three blacks down here, larger. But it is a move like this or occasionally they will all end up black together or all white against the white wall. Almost imperceptible. But he was very. It’s in me. Was very aware of what color would do. Sometimes I think he would make a mistake. And once he did a large canvas for us, again, just as a gift. But 16 feet long. And he got the whole thing done with blue and red and black. And then for some reason, he put a yellow, yellow ochre across the bottom of it. And it always was rather doubtful. And he came here once and said very modestly. I’m not sure about the yellow. And of course, I didn’t say where we are either. But again, the I think out to speak also about the man’s total honesty and frankness and his so many of the observations he made that we would overhear. We’re still remember them perfectly. Once we were driving in Normandy, Louise and San Luis are driving Sandy asleep in the back. I was sitting beside him El-Mahdi up in the front seat and we were discussing our marriages and really pleasant and marvelous they were. And then the course turned to death and Sandy just observed. Well you can’t have it both ways. You can’t have this wonderful life. And then if that only happens to one person that is actually dismal period. Or this had a great, great effect on all of us. Sandy once said, well, if you don’t have the money, go without, which I must say I’ve tried to impress on the boys, not very effectively, but who would, if you would, utter these things or as well? Well, it’s very interesting. Once in Italy, we were driving with them and we came to the Donatello statue and we all got our legitimate equestrian statue by Donatello admiring it. And Sandy finally lumbered out of the car and walked around at once and got back in the car and said his father would like that piece. That’s why the children needed it. But again, the no fooling around or no no covering up or no. So now they’re like this. It was always coming right straight at you. And that’s even true of his daughter, Mary Rohwer. You’ll find Margaret.

Interviewer: In your book, The last picture is the day Sandy died. Can you describe that picture and what you were feeling when you drew it? Think about how we will be looking at that picture as soon as you talk.

Robert Osborn: The day the day Sandy died was really horrible. The first. I was concerned. Let’s see if I can get through it. The day Sandy died was a shock. He had this pain in his chest and how Harry Rowers said, call him Pop. Pop said I would pack your suitcase for the hospital. And Sandy said, no, I will do it. Typical. Anyway, I wish we all were shocked. And I went up the studio and a piece of Irish paper started with this red sky and pretty soon reddish circle. Very much like the jewelry began to appear. That would please me. But that drawing, was it Sandy always when he moved. He was always leaning forward like that. And he’d let gravity. He would put one foot out here and another here. And then he just let gravity carry him across anywhere where he was walking. Always short. Bend over. Little bit. This half hulk of a man going. Going like that. And I drew that. Going off into the distance. But pleased is it. It had that feeling. This this man just disappearing that way. And it was. Well, it was a bad day, but Jerome Wiesner just died. That’s also a bad day. These rare men. And when you know, when you feel something that strongly the drawing is very up, come out much better then. So you just go up there and intellectually do it. Going straight from here.

Interviewer: What do you remember when you recall Sandy Calder.

Robert Osborn: This generous man. This hulk of a man is highly inventive man who could screw with Western sculpture, having been three dimensional and showered from the very start, practically back to man and man? And suddenly this man, Single-handed, moves out into space as an engineer, as the center of gravity, and he could begin to put together a news new, utterly new type of sculpture, exactly like the Wright brothers. Highly inventive man who starting from scratch correcting all previous ideas, and they, with testing and everything else, put together an airplane that takes off and works.

Interviewer: That’s great.

Robert Osborn: Too much hand motion?