Speaker Tell me about how you work together.

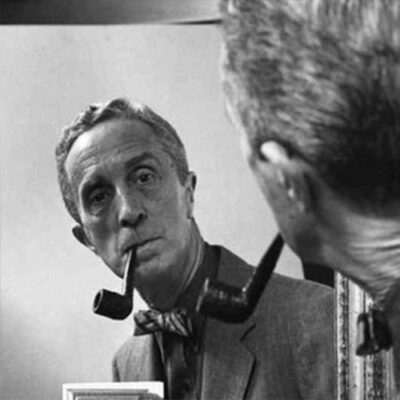

Speaker Norman and I, we worked together in the 1930s. He was illustrating covers for the Saturday Evening Post and I was selling the Saturday Evening Post from door to door. I would put on my roller skates and sling this canvas bag over my shoulder with two dozen Saturday evening posts. Norman Rockwell on the cover. Some charming, lovely picture, I’m sure. There I was then, maybe eight, nine, 10 years old, back in the depths of the Depression. And I’d sling this thing over my shoulder and go out and start ringing doorbells. Now, I was living in a town in North Jersey down on the Passaic River. The depression had really hit hard. There were people there who hadn’t worked for years. And my job was to go round and ring doorbells.

Speaker And when people came, say, you want to buy a Saturday Evening Post and I’d hold this thing up with this charming, idealized America that Rockwell was drawing and it was hard work, they would take me a whole week to sell two dozen of them in that town.

Speaker People came to the door, men and undershirts, women who were breathing beer fumes, you know, people who hadn’t worked, worked in years.

Speaker And looking at this Norman Rockwell cover on the Saturday Evening Post. You want to buy a sweater? They’d say, don’t you have true story? Don’t we have true detective? They wanted to read about vice and adultery and see pictures of mutilated bodies at the morgue. They weren’t interested in this idealized America that Norman was painting. So he was a bust as far as I was concerned, as a working colleague.

Speaker So you were angry at him?

Speaker No, I wasn’t angry at him. I was angry at my mother who insisted that I go up and sell these magazines. But I later saw that if it was Norman Rockwell who accounted for my poor sales.

Speaker Well, I mean, that’s interesting because I guess we think of that image that he painted as being very popular.

Speaker And you’re saying it was an idealized America. He was painting. You know, he was after I grew up and thought about this, I realized what he was doing. I think I have no opinion about Rockwell as an artist. I’m not no Clement Greenberg. But I realized what he was painting was painting us as we wanted, as we thought of ourselves. You know, when we thought of ourselves, we didn’t think of ourselves sitting around and in our undershirts drinking beer all day, hadn’t been to work for who knows how long. He saw what we thought or how we saw ourselves in an interior way.

Speaker And it was an America that didn’t exist. But he made us feel that it did exist. And it was like propaganda, except it was nice propaganda.

Speaker In that era, you know, there was a lot of painting of where the Soviet Union, the Germans, it’s awful propaganda painting of big, robust, muscular people pitching sheaves of hay. And it was awful. You know, it was war like it was to put people in a physical mood for war with. Rockwell was showing us decency. He was showing us that no matter how bad things are, we’re a decent people. And I really think that was important when World War Two came along, that there was a sense that we were a decent people and we were gonna go and and many of us die for that without quite understanding what else we were dying for. But it was because it was a decent cause. We were decent people and the decency that we stood for was being threatened. And Rock Rockwell saw that Dennis and, you know, Americans did that nobly during the war. Who was it? Somebody, I think Eric’s overrides.

Speaker He who was covering the war said he was astonished at the number of young American men, completely innocent, went to their deaths completely innocent of the cause of the war, but because they thought the purpose was decent. And that was what Rockwell did to us all. I think he made us think it was a decent country.

Speaker So even though the man on the T-shirt maybe didn’t want to Byrock. Tell them what Marquart was going did. Sell and they end right at the time.

Speaker Well, I’m not sure.

Speaker Well, I mean, he was very popular, right?

Speaker Oh, he was immensely popular. He was of course, he worked all the time. Not many people. The Depression could say that.

Speaker But I know your friend of many a time I yearned to be carrying not the Saturday Evening Post from door to door, but true story. True Detective. That’s what Americans really wanted to pass those long days sitting home. Nothing to do. You know what a soulless business it is being out of work. You probably don’t know. None of us do.

Speaker Just have to sit day after day, week after week. Nothing happening.

Speaker I mean, people do criticize Rockwell. He didn’t paint the depression, didn’t paint the violence of the war.

Speaker Yes. Well, I think I don’t think it was in him to paint realistically. No, he was painting kind of fairy tale. I think it was a fairy tale America that didn’t exist. But he had a a conspiracy to agree that, yes, this is what America is like. It wasn’t it was nasty. You know, it was it was it was really nasty. Nowadays we see the old black and white photos, news photos of bread lines and men and the depression and how depressing it is to look at that. Men lined up and noticed they always wear hats, they have fedoras on and they have suit jackets on, terribly poor, usually no necktie where they turn, the neckties are gone. But these people who were at the end of the line but still wanted to feel respectable so they’d get in the breath, always wear the hat, always had their fedora on, jacket on, lost the necktie, or maybe it was a stain. By that time it had to throw it away, but it was that intense desire to be respectable. In total adversity. And Rockwell fit into that.

Speaker What did you mean when you said you weren’t sure if the dream that he was finding ever sold really well itself sold later?

Speaker I’m not sure how popular he was really in the Depression. I suppose he was on the Saturday Evening Post wouldn’t have used him so widely. But, you know, Americans didn’t think it began to feel well off until after the war. I’ve always been fascinated by the success of the James Stewart Christmas epic. And it gets a wonderful life, which I think maybe in the 50s or early 60s, suddenly everybody fell in love with this movie, which had been a turkey when it was first made, because the audience, the audience that saw it when it was brand new really didn’t believe that somebody came along in the end and showered you with money just because you were a nice guy. You were Jimmy Stewart. But by the 50s, the Americans are ready to believe that they were finally they begun to believe the Rockwell vision of America.

Speaker That was the height of his success. I guess I’d say problem.

Speaker Well, I’m not sure. I don’t know enough of the history of Rockwell to tell you how that went when he became greatly popular. But he was sort the post used him for years and years and years. I must say, I don’t know much about his independent work.

Speaker You write in the piece about World War Two as being kind of a turning point in terms of America’s willingness to buy into this dream of innocence and decency. And that’s no longer the case now. You speak to that a little.

Speaker Oh, well, that’s a that gets us abroad. A little bit of field of Rockwell, but the World War Two is a really kind of a tonic for America.

Speaker Oddly enough, it’s a strange term to use for such a destructive event. But the country came together because the country people perceived at the core of our cause was decent in a way that they didn’t. By the time we got to the Vietnam War, there was no feeling what we were doing. Was the decent the right thing to do there. People, young men didn’t no longer wanted to die for that cause, for the most part. Many young men and. The reason was that we’d come into a new world that Rockwell had given us the sense of decency in the old in the 30s into the 40s. And we believed it. And I think by the time Vietnam came.

Speaker Oh, we were. We were. We were a little cynical or not cynical or maybe skeptical and smart, smart enough to say, well, what are we doing this for in World War Two? Nobody ever asked what we were doing it for.

Speaker It was obvious what we were doing it for. And nobody had any doubts that it was a good cause and that we should do this to save ourselves, to save decency in the world. Well, it sounds awfully stuffy, but that’s one way of putting it.

Speaker Do you think there’s nostalgia for that world now?

Speaker I mean, when people look at my main street, Stockbridge now famous Rockwell image, I suppose a nostalgia is the is the vice of a decaying civilization. I suppose people are nostalgic for that vision of small town America, which probably never existed anyhow. You know, full of sharp and con men and awful people.

Speaker Small town America.

Speaker I think if you look at the history of small amount of small town America in the 20s and 30s, you’ll find people trying to get out and go to go to the city. You know, they wanted to go to Chicago. They wanted to go to New York. They wanted to go to Washington. They wanted to get out to where the action was. Small town America was stifling.

Speaker But now that we’re all made it to New York and Chicago and we’re very pleased to look back nostalgically and say, well, think what we’ve lost.

Speaker I don’t think a lot of people would go back to a small town given their druthers.

Speaker Do you think it’s going too far to say that Rockwell helped create kind of a national identity or sort of a unifying vision of what America is?

Speaker I’d I’d be think that be going a little far to say that he created any kind of vision of America? I don’t think so.

Speaker You have a favorite Rockwell Rockwells?

Speaker Well, no. My favorites would be those that have pretty much been approved by the passage of time. I think some of them I find a little cloying. I am looking I went recently, went through a lot of old Rockwells, and I was particularly offended by his treatment of small children, these unbelievably cute little boys with their Catholics sticking up and rosy cheeks because I thought I was there when he was drawing that, you know, I was one of those little boys and I wasn’t cute.

Speaker I felt put upon hard, worked unjustly, treated by society and becoming impoverished because I wasn’t selling any Saturday Evening Post.

Speaker Hearing some of them must still have some in family.

Speaker Well, of course, the the famous group of the four, the Four Freedoms is a wonderful example of that kind of thing.

Speaker He did so well. He’s very good at praying, know his people at prayer are always fascinating to look at because of what he does with the hands.

Speaker I’ve always had problem with my hands. I’ve you might I tend to move my hands all the time. I’m shaped. I’m a writer and I shape words with my hands. I’m trying to, you know, should I say reveal or disclose.

Speaker And I’m testing, which is the right word. So my hands have always been a problem with me. But I’m fascinated by Rockwells treatment of hands. They’re beautiful, beautiful hands.

Speaker Doesn’t he have a whole painting of a hand of hands? I think a pair of hands maybe.

Speaker Do you remember the response to freedom from want? I mean, the whole series?

Speaker Well, I don’t I, I, you know, I don’t have an a live memory of it. Remember reading about it.

Speaker Those pictures were out there at the time, you saw them everywhere. You know, when they were when he did them.

Speaker So, Francois, we’re sitting here today. What would the old newsboy say to them? Well, I’d say Norman, who made life hell for me when I was a kid, trying to make 25 cents a week.

Speaker But you had it right about America.

Speaker I like the phrases in the piece like he tell the lie to tell the truth.

Speaker Yes. Well, somebody is defined. Art is that art is a lie which helps us to perceive the truth. And I think, in a way, Rockwell fitted that definition. He did tell us a lie about America, but it helps us.

Speaker It helped us to perceive a deep truth about ourselves. And I I respect him for that, even though he didn’t do much for me when I was a kid.

Speaker Do you think he believed the lie? I wonder. I don’t know. I don’t know anything about him.

Speaker I don’t know anything about him.

Speaker I just don’t like, you know, any or any artist must paint what the world the way he really sees it. You know, you can’t. I don’t know about painters, but I do not know about writers. A writer can’t fake it.

Speaker You’ve got to write the world as you say it. You know, you try to be a hack. It’s unless you’re a born hack, you can’t be a hack. I’m sure Rockwell was he couldn’t the pain of the world he didn’t see. You know what? He you just can’t fake that kind of thing. That was an expression of the inner man and had to be right. You know, painter paints the world. He sees that offends and annoys a lot of people, doesn’t it? Because you world, a painter sees often is not seen by anybody else but the painter himself. For the longest time, then it becomes a cause. Everybody. Oh, that’s what it looked like then. You’ve got the Vincent Van Gogh problem. Poor Vincent. His work selling for 10 million dollars per painting. By the time they see what he was. Oh, that’s what. That’s what he was. That’s the world that he saw. I see.

Speaker You know, well, that didn’t happen to Rockwell that he got a lot of fame during. No, no. He was one of the lucky ones.

Speaker Well, that’s great. I think he would have. And I think we missed something. Well, let me just check. I think. I think you did it.

Speaker I didn’t want to ask you. It was so wrong. I do remember his 60s paintings. You know, the whole issue. He never painted blacks except as servants. No, I was out of touch.

Speaker But that was the 60s was another time for me.

Speaker Pam, do you have any.

Speaker Righteous, I mean. I can’t hear you, I’m deaf on one, she said, whether any writers you could think of her right on a rock while I am.

Speaker Are writers who write who wrote like Rockwell.

Speaker No, I can’t really think of any Goodwins who who wrote that. If you think of the writers of the Depression, well, you think preeminently. You see John Steinbeck, who painted a very cruel America. Ernest Hemingway, who left America. He went and did France. And then he romanticized it. Scott Fitzgerald, there’s a bitter sweetness and Fitzgerald that you don’t get in Rockwell. Fitzgerald can be very sweet, but underlying it is always a bitter ending. No, I can’t think of any good writers who did what Rockwell did with painting.

Speaker Steinbeck’s Main Street was very different from Rockwell’s main street.

Speaker Well, it was Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, the great painting.

Speaker He painted Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath as the story of the exodus from the farms of the Dust Bowl to California and the abuse that these people put up with when they get to California and the poverty that they have to endure. And it’s a family. I mean, in that sense, we’re in Rockwells court here who’s a very close family geodes, the Joad family.

Speaker They’re intensely bound.

Speaker That’s the basic unit, the geodes, the family. Is it. The state is against them. The laws against them. Every economy is against them. The bankers are against them. But they have each other. And that’s what enables them to endure to the very end. And in that sense, that there’s something wrong. QUILLIAN In that that the idea of the family as these great survival unit of American society.