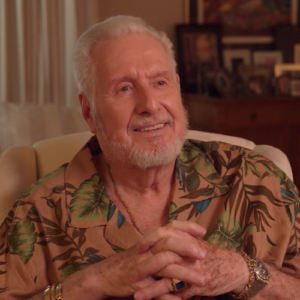

Todd Boyd: This was when Frank and Sammy and Dean Martin. Did this ruin a reunion tour in the late eighties? And I saw the first show after Dean Martin had gotten the boot at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit. But the story is that my father and my stepmother were going to see, you know, the Rat Pack. This is their era. And my father, for whatever reason, couldn’t go. So they made me go with my stepmother. The problem is, it was in the middle of March Madness and I wanted to see basketball. I’m like, Why do you want me to go see these old men, Frank Sinatra and Sammy? I’m like, mad because I want to watch basketball game. But I you know, I had no choice. I had to go. And so I’m sitting there angry and try and, you know, this is before social media. So I couldn’t check the score. And every now and then I’d run out to the concession stand to see if I could catch a glimpse. But Sinatra comes on. And so that was fun. And Sammy comes on, and it is the most incredible performance I have ever seen in my life. And when I say most incredible performance I’ve ever seen in my life, I’m talking, singing, dancing, sports, any performance. I sat there and watched Sammy Davis and, you know, I’m in my early twenties. This is a few years before he dies. And his versatility, like his energy, just the range of his skills. I forgot about the college basketball game. I forgot about March Madness. And I later thought to myself, it was so important for me to see this performance because these guys are not going to be around forever. And so to participate in something like that left this memory with me that I share with people to this day. Like I say, Sammy Davis is perhaps the greatest entertainer ever based on just his versatility. And I wouldn’t be able to say that in the same way had I not seen him at Joe Louis Arena back in the late 1980s.

Interviewer That’s great, man. But, you know, as a professor and a cultural critic, what is what is Sammy Davis to you represent to black people in the fifties and the sixties and the seventies and in the eighties? He represented those different decades.

Todd Boyd: I think when you talk about Sammy Davis in the, say, fifties and sixties. You’re talking about a black celebrity from an era when there weren’t a whole lot of black celebrities who appealed to broad audiences. There may have been people who were appreciated amongst black audiences, but when you start talking about, you know, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Sammy Davis, people like this, you’re talking about individuals who had popularity and celebrity and visibility in a very, very different cultural environment. So it just really weren’t that many other people and certainly not very many people, if any, who were hanging out with Frank Sinatra and, you know, going to Las Vegas and involved in all these things that really were just off limits for most, if not all, black performers, by the time you get to the seventies, though, things are very different. You’ve had the upheaval of the sixties, the civil rights movement, the Black Power movement. You’ve had this change in terms of black culture. You’ve had the emergence of a figure like Miles Davis, who was a very different celebrity than Louis Armstrong or Sammy Davis would have been. And then by the seventies, you also have blaxploitation and cinema, R&B, James Brown, different era, different celebrities, different styles. If you live long enough, you might go out of style. And I think that’s what happened with Sammy Davis. So when you think about Sammy Davis from the seventies hugging Nixon, it’s maybe less problematic. Problematic, but maybe less so if he’s not doing this and perhaps the blackest era in American cultural history so set against, you know, blaxploitation and Richard Pryor, Sammy Davis hugging Nixon looks perhaps a lot worse. Maybe it looks worse anyway, but it looks a lot worse than it would have looked maybe ten years earlier. And then, you know, after that, he’s just a legend because by the eighties, when you mention his name, you’re talking about his history and you’re talking about what he’s been able to accomplish as a significant black performer over a long period of time. So in each one of those decades, I think he goes from being a celebrity in a sort of environment where there weren’t very many other transcendent black celebrities to being a black celebrity when the culture had changed. And he was much older. And perhaps at this point his image was not seen as like so compelling and current and significant in the way that it would have been, you know, in times before.

Interviewer You know, this is interesting. You know, I grew up in the fifties and sixties, and when I used to see Sammy Davis on The Ed Sullivan Show or the Mike Douglas Show, and it was like, Wow, man, because he could dance, he could sing, he could.

Todd Boyd: Do the do everything.

Interviewer Right. The fastest guy.

Todd Boyd: Right.

Interviewer There. And then when I first got in the film business around 72, 73, I think he was in Chicago. He did. You know, he went to do push right projects. Right. And I’m watching this documentary called Save the Children.

Todd Boyd: Yes, Yes.

Interviewer Boo!

Todd Boyd: And Marvin playing the piano. Right.

Interviewer And he was like freaked out. I mean, what was it about, say, Sammy, He always seemed to need so much love and so much, you know, adoration.

Todd Boyd: Well, you know, it’s like I think when you think about his background. He’s a guy who was performing since he was a little boy. I mean, sort of parallel. There is Michael Jackson. And of course, Michael Jackson would be someone who would seem to have needs in terms of attention and such himself. So I think there’s perhaps a lot of parallels there. When you grow up on stage, the way Sammy Davis grew up on stage, love is often the applause from the audience. It’s not the sort of emotional love that one might be accustomed to from their parents or what have you. Instead, it’s about you go out and perform, and if you do a good job, people applaud. And I think after a while, this becomes something like a drug. You need this approval and your performance, if it’s up to par, will elicit this approval. But of course, you don’t live your entire life on a stage. There are moments when you’re not on stage, and maybe at this point it’s harder to get that sort of approval which you consider to be love other than when you’re performing. I mean, in today’s society, if you have a Facebook page and you post something, people like it, that’s a form of approval. You can get this approval on a regular basis. But if you’re Sammy Davis and your identity is as a performer, and when most people were going to school, you were performing and audiences were applauding for you. There’s a point at which you perhaps need that and you need it all the time. How are you going to get it when you’re not performing? Who are you when you’re not on stage, when the lights go down? And I think for someone like Sammy Davis, this was a constant struggle.

Interviewer You know, I think as Sammy, I also think of Harry Belafonte.

Todd Boyd: No question these.

Interviewer Guys are the same generation.

Todd Boyd: Yes. Sidney Poitier.

Interviewer And Sidney. So when we interviewed Harry, you know, Gibney interviewed Harry for Sinatra about Sammy and Sinatra and the Rat Pack. You know, Harry is like, you know, he felt like Sam. He was he was Tom. And out there, you know, he was he was denigrated. So, I mean, I mean, when I watched Dead Man attacks up as a young man, I thought it was great. As I get older now and watch, I said.

Todd Boyd: Well, a little harder to watch.

Interviewer A little harder to watch. I mean, what was this relationship that Sammy have with the military from your perspective?

Todd Boyd: Well, I mean, the thing about Sinatra and Sammy’s relationship is you’re talking about an era when it’s very different. And now in some ways, Frank Sinatra would have had to approve of Sammy Davis hanging out with him. So there’s a very different power dynamic. Like Frank Sinatra is the star. He’s the white star. He looks benevolent by befriending this black performer. And of course, at this time in Frank Sinatra’s career, he really was someone associated with what were thought to be progressive ideas about race at that time, certainly evidenced by his relationship not only with Sammy, but with the community of jazz and other performers and such. But it was very clear that Frank Sinatra was the man and Sammy was his boy, and I mean that literally and figuratively. And watching Sammy Davis, it was often the case that he performed as his boy. So there is a lot of timing, Kooning, buck dancing, the sort of stereotypical performance. There’s a lot of Willie Bass, man, Tam Moreland, Rochester. I mean, a long list of Stepin Fetchit performers in Hollywood who, you know, were offering these very demeaning images of African-American masculinity. And it was clear in their performance that they were subservient to white men. Sammy never seemed to have a problem with this. And so I think looking back on it, it’s difficult to watch because we have such a different image of how black men conduct himself in public from the sixties forward. So Sammy’s willingness to be Frank Sinatra’s boy would, I think, in future generations be something perceived negatively and stereotypically. And it never seemed as though Sammy did much to sort of push back against this.

Interviewer Why do you think he didn’t?

Todd Boyd: I think Sammy Davis is like all of us, a product of his generation. And again, you look at his background, he didn’t go to school. He grew up performing. So he’s hanging around adults. He perhaps doesn’t form the same sort of friendships and goes through the same sort of social circuit that most of us would go through just growing up. He’s a kid who’s performing and he’s good, but he’s not educated, not in a formal sense, certainly. And I think for him it was always about approval. And whenever you’re in a position that you’re seeking someone’s approval, you put yourself at a disadvantage. And when you factor in the racial politics of that era, you’re a black person. You’re seeking white approval. What is it that you’re willing to do to get that approval? Well, so if you’re Sammy Davis and you’re willing to, you know, go as far as possible to get a pat on the back from a white person, over time, when people see you, they’re not going to want to embrace you because you’re going to seem like a relic. And I think ultimately, as times change from the fifties and sixties, seventies, going forward, Sammy might have been popular with white audiences, but for a lot of African American audiences, it was just too difficult to embrace a figure who looked like someone from the past. Doesn’t mean he wasn’t brilliant. You know, Louis Armstrong, we can’t have a conversation about American music without first talking about Louis Armstrong, but it’s really hard to watch Louis Armstrong perform this sort of stereotypical timing that he did. But you can’t forget that the guy’s brilliant. Same thing with Sammy Davis. Brilliant. But I honestly think you’d be negligent if you didn’t point out the level of timing that was associated with his persona. Some people get all pissy and they wouldn’t say that and maybe upset that I’m saying it. I think Sammy was brilliant. I think he was an incredible performer. But the timing made it difficult for a guy of my generation to ever fully appreciate him, because that was just hard to accept.

Interviewer Yeah, you know, it was because when I was a young man in college, I was a. Jay and I listened to jazz greats Ray Charles, you know, Eric Dolphy.

Todd Boyd: Yes, sir. And after lunch.

Interviewer Yeah, the last one. I would play Louis for a while because I used to say was lost an Uncle Tom. But as I got older and I realized, you know, I always knew Louis Armstrong is the greatest jazz improviser ever, right? As I got older, I said, Oh, this one. I can’t. I can’t. I think I won’t deal with that. But. Well, he plays that trumpet.

Todd Boyd: We’ll see. When Louis Armstrong put the trumpet in his mouth. All bets are off. It’s as you listen to the music. I think also we’re both probably products of the sort of post Miles era, because once Miles comes on the scene here, you have a celebrity who embraces his blackness, who embraces a certain militancy, who embraces what years later people might call black power. Miles was a black celebrity who was very comfortable being black. Sammy Davis was a black celebrity who wanted you to forget about the fact that he was black. And I think that’s the difference. And so if you come along after Miles, as I did, and then you look at Sammy Davis, particularly when I’m a kid in the early seventies, and I just went to see Shaft and Superfly and here’s this guy singing The Candy Man. I mean, the song is cool, but I just saw, you know, Shaft and Superfly and I just heard Curtis Mayfield on the radio. So this old man that I’m looking at is difficult for me to appreciate at that time in my life, his significance, because I was surrounded by so many other empowered images of African-American culture that Sammy seemed like not only an old man, but someone politically not very interesting, right?

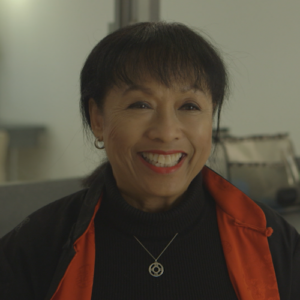

Interviewer Where do you think Sammy stood in terms of this? What was happening in the civil rights movement? I mean, we all know we had the right Sammy did go there, but he was never as aggressively political as were Harry Belafonte.

Todd Boyd: Well, Harry Belafonte is someone who’s come to be known and closely associated with the civil rights movement directly as a participant and also just as a sort of figure from that era. Sammy, I see more like a celebrity. So when Sammy showed up on the civil rights scene, it was like making a celebrity appearance. It didn’t seem as though there was the same level of commitment and actual investment in the activities taking place. It was more like a photo op, perhaps. He was a famous guy and of course, if he showed up, it would attract attention. But based on his actions, didn’t seem like he was invested in what was going on. The same way somebody like Harry Belafonte or Muhammad Ali or other figures from that era were sort of actively participating in what was taking place.

Interviewer Excuse me. Sandy and his book. Yes, I can. Mm hmm. But in the light of that book, he’s always feeling, you know, like he’s getting he’s getting a lot of flak from the black community for being too white. You know, and he always felt like every every letter that he used, every time he rose up on the ladder, black people, the communities that you feel that you’ve you’ve forgot where you come from. Right. And really know that and really know that. And he never he never could get over the fact that he felt like, here I am a success, I’m making it. But the black community.

Todd Boyd: They want more.

Interviewer I, I forgot. Right.

Todd Boyd: Well, I think you know and you can see this trend with any performer who has been doing it since they were a child. You know, Sammy Davis, when you grow up on stage and you’re not educated. I mean, you just he’s a performer and, you know, you can’t put £10 kid in a £5 bag. Like if you’re on stage performing from the time you were a kid, there’s not a whole lot of time for other things. So maybe Sammy didn’t have the sort of elevated racial consciousness that would even allow him to understand why people wouldn’t be so impressed by him living this lifestyle. Clearly, that was off limits to them. So a lot of people look at him and they didn’t look at him and say, I’m proud or, you know, I’m glad to see you doing well, because they didn’t see Sammy Davis necessarily giving back in the way that people like to see giving back. It’s like, do you want to be around us? Do you want to hang out with us? Do you want to like, you know, Harry Belafonte didn’t spend his time in the hood, you know, but he was someone who was seen as actively involved in what was going on. Sammy was in Vegas with Sinatra and Dean Martin. It’s like his lifestyle didn’t appear to reflect the lifestyle of most African-Americans in the country at the time. It seemed he’s, you know, dating white celebrities. He marries a white woman. He’s traveling to places that are off limits to most common people. It just didn’t seem, I think, to the populace of African-Americans that what Sammy was doing had any real relationship to their own lives. And as it came to racial issues speaking up and such, he wasn’t doing this. And so I think it’s easy for people to sort of challenge him and say, yes, you’re successful, but we want more. We’re not satisfied with you just being successful because you seem so distant from our reality.

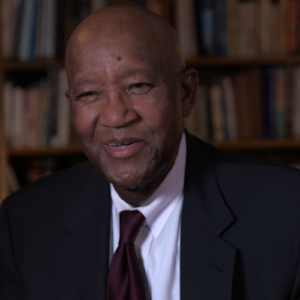

Interviewer How would you compare Sammy to James Brown? They both. They both got tied with Nixon. How would you compare these two? These two great.

Todd Boyd: Performers? I mean, and again, you know, people get mad at me for stuff like this, but this what I do. Sammy Davis and James Brown are incredible performers. They were not intelligent men. They’re not smart men. They’re not educated men. And I’m not saying everybody who’s political and conscious is educated necessarily. But if you look at their background and the time that they came up in the world, I mean, James Brown is a guy that, you know, South Carolina, Augusta, Georgia. I mean, what in both cases, Sammy, these are self-made men. So when James Brown and Sammy embraced Nixon, to me, looking at it, I looked at it as an act of ignorance. It’s like they don’t know. They don’t get the sort of, you know, full sort of magnitude of what their gesture means and how it’s going to resonate. They have an audience with the president of the United States, and perhaps they’re excited about this. Perhaps they go a bit too far in demonstrating their excitement. James Brown seem to be maybe a little more weary of this connection with Nixon and Sammy, who embraced them. You know, and of course, when you look at the transcripts of the kind of things Nixon was saying about someone like James Brown behind his back, it clearly indicates where Nixon was at on this issue. James seems to be sort of taking advantage of whatever access he has. But honestly, I never thought of James Brown as, you know, some sort of political revolutionary, even though he’s talking black capitalism. Well, that’s sort of simplistic. And so for this reason, Richard Nixon can say, yes, I support black capitalism. What does that really mean? I would imagine black capitalism meant something different for Richard Nixon and what it meant for James Brown in the same way that what does it mean for Sammy Davis to go and embrace Richard Nixon? Well, this is what Sammy Davis always did. He’s performing. But to do this in the early 1970s, particularly considering how Nixon had come up, this whole Law and Order Southern Strategy campaign, Sammy’s tone deaf, he doesn’t understand what the people in the street see when they see Nixon, because by this point in time, he’s so removed from the concerns of everyday people that he’s just engaged in another celebrity performance. But when this goes out to the public, they reject it out of hand. And I think the same is true with James, but James is able to recover from it in a way that maybe Sammy Davis never was.

Interviewer And for Sammy, there’s a tipping point. Yes. Yes. We can’t do it today.

Todd Boyd: Exactly. We’re done with Sammy like James. Okay, that was not cool, But we’ll overlook it because on a daily basis, James was still representing, you know, as the guy who said, I’m black and I’m proud. I mean, so James, on a daily basis, was still representing the culture, even though, you know, when you got into certain areas, he was maybe out of his lane, Sammy was in his lane. And that’s maybe part of the problem.

Interviewer But, you know, you know, it’s weird because Sammy, he’s in the service in World War Two. He gets right, he gets beaten up, he gets painted white.

Todd Boyd: Right.

Interviewer But he’s really I mean, you would think that it was it would burn a different kind of fire in him. Maybe as a part of that, you know, as a cultural critic, maybe was a part of this notion of African Americans or Negroes back then. It was the assimilation. Is that into right. We want to assimilate. We don’t want to make any waves.

Todd Boyd: Well, again, you know, I think we’re all products of our generation. And so, you know, as someone born in the 1960s who came of age in the 1970s, I see Sammy Davis assimilation and issues like this from a perspective formed in the sixties and seventies. So assimilation during that period of time that I was coming of age was a bad word. You know, I remember Charlie Mingus meditations on integration, like people were not so in a hurry to go in assimilate. This was a question in the black community. It was not like, Let’s go and assimilate. It’s like, what are we giving up and what are we gaining? It was a question. It was a series of questions and it went on for a long period of time. And in some ways you could say the argument continues maybe in more nuanced forms today. So when you talk about assimilation. You know, Sammy Davis comes along at a time when it’s really not possible to accomplish very much. And he’s one of the few who’s able to accomplish what he’s able to accomplish. He’s in a much rarer set of circumstances than people would be in subsequent generations. So I think, again, not only is he not educated, but timing wise, this idea that you would question assimilation is something that maybe comes up long after Sammy’s come of age. And so he’s just really not connected to the sort of circumstances or circuits or people where he would be informed about. Maybe you want to do well, but what does that mean? What does assimilation mean? Does it mean making money and buying material possessions? Does it mean selling your soul? Does it mean compromising your identity? What does it really mean? I think people reached a point where they decided, yes, I want money and material possessions, but I still want to maintain my identity. I still want to be black. And Sammy comes along prior to this becoming, I think, the way that people went about carrying themselves. And so, again, it’s why it’s difficult to sort of deal with his image politically, because it’s an image from such an older time. And that consciousness really wasn’t available and often wasn’t represented by the handful of celebrities who had reached that status.

Interviewer Right. Absolutely. I mean, think of it this way. Sammy supports JFK when he runs for president in 1960. Right. When he gets elected, he can’t even go to the inauguration because he’s ready to my bread.

Todd Boyd: Exactly. You know, his Sammy’s support of Kennedy in 1960, a turning point election, because this is a time when a lot of African-Americans are still Republican. And Kennedy is one of those moments when the shift starts to occur and subsequently it occurs much quicker by the time you get to Lyndon. But here’s Sammy Davis supporting a guy, helping get him elected, and then he is a celebrity with this access. But he can’t go to the inauguration because he’s in an interracial marriage. And so, I mean, that’s humiliating. And, you know, Frank Sinatra is the one who has to go and tell him that he can’t come. And this is the reason why it looks as though he’s trying too hard that he wants their approval. And I think this is why many people are just sort of slow to embrace him because it’s like he wants their approval and he’s relinquishing his own power in the process. Any time you go around seeking other people’s approval, you put yourself in a difficult spot because the approval is about someone else and not about you. And you seem needy and also vulnerable. And this is not the way in which black celebrities would be seen going forward. And so he kind of stands out as being needy and vulnerable. And then people start to say, what is it you think you’re going to get? Like, you know, you want their approval, but what are you going to do with it? And what does that really mean? How do you feel about yourself? It made it look as though Sammy Davis didn’t have a strong internal core and sense of identity about himself because he was seeking this approval elsewhere.

Interviewer You know, I remember I saw in the seventies came around in the late seventies. He was trying to be really hip. Yeah. You know, different look, the rings and all that stuff and hippie.

Todd Boyd: That sort of hippie chic. Yeah.

Interviewer You keep saying. I guess it was his needs to stay relevant.

Todd Boyd: Well, I think any time, you know, when you look at an entertainer, if they’re around for an extended period of time, you know, history poses challenges. So the Rat Pack by the late seventies is a long time ago that’s played out. So, I mean, Sinatra, Sammy Davis, they all tried to make that transition of Nehru jackets and, you know, sort of hippie chic And I mean, Miles, you know, Miles, when he changed his old attire as well as his music. I think that’s just one of the things, you know. Well, I’m one of those I’m one of those people that like once my shifts. I like the old miles better. I’m not like 56. I like miles up to in a silent way. I think I can appreciate Miles after that. I mean, Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson and all that is cool, but. I think Miles is too old. Herbie Hancock does a better job with that music at that time than Miles because he’s younger. And then there’s a point at which Miles looks like an old man and some crazy, like, uniform. But he didn’t want to be a guy in a suit and tie his old life. So I can appreciate the desire to sort of push forward and go against the grain. But there’s no way the miners of the seventies and eighties is as cool as the miles of the sixties and fifties.

Interviewer That’s true. That’s true. I mean, so, you know, Sammy was still trying to be cool, but they couldn’t be so cool. And they.

Todd Boyd: Couldn’t be. No, no, because cool is a thing that changes, you know, with time. So it was cool in the fifties, may not be cool in the sixties and was cool in the seventies. May not be, you know, cool in the eighties like so. And one of the worst things in the world, you know is seeing a person this. Past a certain age, trying to act younger than they really are. You know, the proverbial guy in the nightclub with, you know, his shirt unbuttoned and, you know, tons of jewelry trying to attract young women. It’s like that’s not a good look. And that same idea can be extrapolated, I think, to Sammy trying to be cool in the seventies. But now the definition of cool is blaxploitation or funk or, you know, what Richard Pryor was saying on stage. And when you have a guy like Richard Pryor or Ryan O’Neal or George Clinton, you know, and you’re looking at, you know, Julius Erving, you’re looking at people like this and you compare Sammy Davis, it’s clear he’s not only not cool, he’s old. And I think when you deal with popular culture, you’re often dealing with age in one way or another and how well people transition from one phase, one generation to the next. Sammy struggled with that because and so did Sinatra and others from that generation, because as things changed, they weren’t always able to change in a way that seemed authentic.

Interviewer Right. You know, that’s why I interviewed Sam. He’s against his fourth child, Manny Davis.

Todd Boyd: How old is he now?

Interviewer Like 36. 37? Mm hmm.

Todd Boyd: And so this was right before he that long for his name. Okay.

Interviewer Out of these adopted. Okay. You know, but he was telling me that God hasn’t seen this past, you know, he close to death that the IRS was coming. Take him and take him with taking the stuff. Mother’s house, man, this guy was in such debt. I mean, how can you be, like, one of the most successful entertainers in the history of show business and leave so much debt?

Todd Boyd: Well, you know, when you talk about the IRS going after Sammy Davis, you think back to Jesse Owens, you think to Joe Louis. I mean, you know, for a long time people would joke about, you know, if you were a black celebrity, how they were going to get you dope women. The IRS was always on that list. Like, you know, Sammy Davis is a guy who made a lot of money, but black people aren’t making a lot of money. Where do you get the knowhow in terms of how to manage this money? The money’s coming in. Uncle Sam has his hand out. There are other, you know, obligations. You can’t just buy jewelry and cars and houses. And so it was kind of sad near the end of his life to see that this is what he was dealing with. But, you know, he was never educated on how to manage his money. He seemed very indulgent, as a lot of people are. And it’s sort of unfortunate. But also at the same time, you consider what he gave America, like Joe Louis, Jesse Owens and others. It’s like Uncle Sam was his money and he could care less that you can tap dance and imitate Cary Grant. He wants his money. And if you don’t have it, you know that’s a problem. And so Redd Foxx, same thing. I remember right before Redd Foxx died, there were all these stories about, you know, the IRS coming in and taking a jewelry off his neck is really sad when you hear stories like this, because someone who’s been so successful now is in this position where things are being taken from is very humiliating. But in another way, you could look at him and say, this is what America has in store for the black man. This is what, you know, like you give us the best of your talent and we appreciate it and danced to it and sang to it and celebrate it. And then when the time comes, he is a bill. And if you can’t pay it, that’s on you. So it’s not purely coincidental. It speaks to the sort of plight of many black men throughout the history and black women as well others. But certainly the prominent cases have been black male celebrities over the years from a particular time who ended up with tax problems. And it’s unfortunate because they’re old and they don’t necessarily have anything else to contribute in terms of their talent. So now the bill comes due. It kind of speaks to the cold, harsh, dismissive way in which America is often dealt with of some of its black subjects.

Interviewer And right when one one as sad, these will send his songs with that guy to be me.

Todd Boyd: Got to be me.

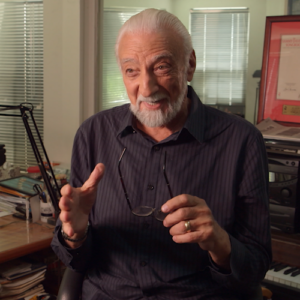

Interviewer What do you think that meant to him? I got to be me, me, me, Sammy Davis.

Todd Boyd: I got to be me. I got to be me. You know, when I think about that, I think about hip hop, which seems strange, but, you know, there’s been a saying in hip hop a long time. Dude, do me do you do me? You know, do you do your own thing? Some variation on that. I got to be me. So that sentiment has been around for a long time, long before hip hop. Sammy Davis I Got to be me. It’s like I want to be my own person. I want to determine for myself how I engage with the world. And when you think about the criticisms he got from members of the black community, that he was too white, maybe he’s saying, like, I got to be me. Like, you know, I’m this celebrity who’s been exposed to white culture and maybe you don’t like it, but I have to do my thing. And then maybe on the other hand, there are some racists who are suggesting we don’t want to see you be so visible and we’re not happy about the fact that you’re married to a white woman or you’re dating white women. All these rumors about, you know, I was I got put out, you know, we’ve all been hearing for many, many years, Sammy, saying, hey, I got to be it’s about personal expression and autonomy, ultimately. But Sammy’s version of being me is going to be different from someone else’s. And I think when you consider the criticisms he encountered, it’s really his sort of emphatic statement in terms of I need to do my own thing is just another way. As I say, people in hip hop say, I got to do me. That’s what Sammy is saying, but he’s saying it long before hip hop ever came around. And he’s saying it in a completely different historical context.

Interviewer I mean, dozens of some some words about Sammy Davis, Jr. You give me your reaction.

Todd Boyd: Prodigy I mean, you’ve got a kid who’s on stage at three years old. I don’t know what I was doing at three years old, but I wasn’t on the stage tap dancing. So. PRODIGY Yeah, definitely.

Interviewer PRODIGY Impressionist.

Todd Boyd: You know, as an impressionist, honestly, that might have been the most impressive aspect of his performance style to me because he was I mean, he was great at whatever he did, But you hear this guy imitating, you know, these white actors and he sounds and looks just like them. It’s really that’s what caught me as a kid when I saw him doing that. I’m like, Wow, this is very cool. So he was excellent as an impressionist.

Interviewer So the saying I was saying when I first heard Sammy Do, Cary Grant and Jimmy Cagney, and I was like, Whoa, this guy was something. I was like ten, 12 years old or something.

Todd Boyd: Yeah, I mean, I remember I was a kid, so I’m remembering seeing my first recollections of Sammy Davis is probably on The Flip Wilson show. And I think I saw him do Cary Grant, Jimmy Cagney, maybe did Humphrey Bogart someone else. And I didn’t know who these people were necessarily when I saw it, but I had an idea, and I know he was acting and sounding different than he normal. It sounded like I’m like, Wow, he can be other people. Like, I think that’s the moment when I’m like, That’s what an actor does. It was to me revelatory because I’m like, That’s Sammy Davis, but he sounds like someone else, and it’s so convincing for a black guy to be able to imitate these popular white movie stars and and be so convincing was incredible. I’ve always thought that his impressions were maybe the aspect of his overall performance that, like, you know, was the best because people don’t talk as much about that. He was great at everything. But man, those impressions were, wow, they were unbelievable.

Interviewer You know, when he first started doing those impressions in the in the late forties, there’s that little bastard that we like real great, you know.

Todd Boyd: He said, Right, right. You will get us in trouble. Yeah. Yeah. Very different a period of time, like a black guy. I mean, you think about the tradition of performance in a minstrel tradition. You had white guys putting, you know, burnt cork on their face and then black guys putting burnt cork on their faces. Like, we can accept you if you’re a black performer, if you play to this, you know, stereotype of blackness and you sort of think about that. And then later Sammy is like, I’m going to flip this because I’m a black guy, but I’m going to imitate a white guy. There’s something about that in a sort of changing up from one race to the next at its time. That I think was really important and also something that scared, you know, his father and Will Mastin, because it’s like you’re going to get in trouble. You shouldn’t be doing this because the rules of performance on the stage were so strict. So this was, I think, really groundbreaking at the time he did it.

Interviewer He’s breaking that. He’s breaking that. He’s breaking, breaking the rules, then. Yeah.

Todd Boyd: Yeah. And that’s the thing is, you know, a lot of performers may be breaking the rules in one generation and conforming in another. And so if you live long enough, that’s often what happens. What was revolutionary in one instance is commonplace in another. Sammy was breaking the rules when he was imitating white guys in the late forties, when he’s attempting to imitate what many people consider a white lifestyle in, say, the sixties and seventies. It’s very problematic and people reject him for these things.

Interviewer Singer.

Todd Boyd: Incredible singer. Great singer. As a kid, Mr. Bojangles the Candyman. But then I later went back and, you know. When he does EO 11 from Ocean’s 11 in the film. And then, of course, Scorsese. He uses that in Casino. I have a record. I listen to all the cards, and Sammy Davis would Count Basie, anybody? Singer would Count Basie is going to sound good. Sammy Singer would Count Basie. This is a. You know, aspect of his career. People don’t talk about a lot these days, but, you know, the guy keeps saying he’s a great singer and you couldn’t get up on stage with Count Basie and not be up to par. And Sammy held his own right dancer. Oh, he’s one of the greatest dancers ever. I mean, when you talk about dancing, you know, Bojangles, Bill Bojangles, Robinson, Hines, Hines and dad, Sammy Davis, I mean, Nicholas Brothers. Oh, man. I mean, you know, this is royalty. My father used to call them board beaters. Well, as the board beaters go, Sam is one of the great maybe the greatest ever. I mean, Bojangles might argue with that or fair. Nichols might argue with that. But I mean, you know, he’s incredible, incredible dancer. Incredible. When I saw Sammy Davis at Joe Louis Arena in the late 1980s, this is the heyday of Michael Jackson. Heyday of Michael Jackson at one point during his performance. Sammy Davis, Moonwalks. Now, this is a much older man and Michael Jackson. And the moonwalk was impeccable. Michael was incredible performing, incredible performer. Sami, in that instance, took Michael’s whole thing for me because it was his old man doing what? A young man. Had done and made spectacular. And Sammy did it like that’s not even a big deal. The nonchalance with which he did it, when I saw him at that performance and that’s the thing I remember, is because, you know, Michael Jackson, born a few years before I was I grew up, you know, Michael Jackson, the Jackson five, that was part of my childhood. And here I am now as a young man in the late 1980s. And Sammy Davis comes along and he’s like, oh, young dude, I got this. You know, this is no big deal. And so for me to be able to see that is older guy was as good, if not better. Then Michael, who was associated with this, was the point at which I’m like, this guy was really, really significant because as talented as Michael Jackson was, Sammy, I think, is that much more talent. And to see that and come to that understanding as a young man was really important in terms of how I understood the evolution of culture.

Interviewer Survivor.

Todd Boyd: No doubt. No doubt. Great survivor. You know, you talk again about age. You talk about a guy who went through several decades. Seventies. He’s still fight and he’s been doing this thing for a long time by the seventies. But he’s still making new music. And I mean, even again, this is what, late eighties when he’s in the tap dance movie with Gregory Hines. Tap, you know, when he’s in tap with Gregory Hines, the whole tradition of dance and he and Gregory Hines and you see him in this movie as an actor, it sort of hearkens back to, you know, his glory days. He he survived in. You know, he was a relatively young man when he died, considering he’s in his sixties. He’s still performing as long as he possibly can. He looked ill right before his death, but he’s still you know, he’s making movies and he’s trying to survive.

Interviewer Right. Right. Provocateur.

Todd Boyd: I wouldn’t call Sammy a provocateur, though. He was provocative and provocative for the wrong reasons. Well, see what I think of a provocateur. I think of Miles playing with his back to the audience, which you can interpret as kiss my ass or however you choose to interpret it. You know, I think of Miles saying, So what? You know, like, so what? You know, somebody like poking and prodding people, you know, like, I’m not going to follow the rules. I’m not going to. Sammy was not that kind of provocative. Richard Pryor provocateur. I’m going to say something really scandalous and and see your reaction. Muhammad Ali like, you know, I’m going to predict the round that I’m going to knock my opponent out and I’m going to rhyme before I like whip your ass. Like this is what I would call a provocateur, someone attempting to provoke a reaction from those paying attention to them. Sort of confrontational, perhaps a bit in your face. This is my definition. I don’t see this with Sammy Davis. It might have been provocative for him to marry my Brit, but I guess it depends on who’s being provoked. Well, some racists are very unhappy with this. And then on the other hand, there are perhaps black people who see him as selling out. So it’s like you’re offending different constituencies for different reasons by one act. But I don’t think it was conscious. I don’t think he was. Dennis Rodman in a dress. I mean, you know what I think of provocation. I think of someone who consciously does something against the grain in hopes of provoking a reaction. I didn’t necessarily see that so much with Sammy Davis. I saw someone always willing to go along with the program, go along to get along, seem to be his thing, as opposed to provocation.

Interviewer Goodman’s criticism. In the last 20 years of his life. He was right down to this.

Todd Boyd: Yes.

Interviewer Yes, he seemed to be. I mean, he had he was still a swinging guy and hanging out with the and a whole different lifestyle with her.

Todd Boyd: Well, without voice in the last 20 years of his life, he seemed like someone who had sort of settled into what would turn out to be, you know, the final chapters of his existence. It’s from the earlier period in his career back in the fifties and early sixties when stories about him and who is it not? Lana Turner. Kim Novak. Yeah. Yeah. There’s these rumors about Sammy dating Kim Novak back in the fifties or again when he marries my Brit, like, you know, Sammy on the scene, Sammy with the Rat Pack. He marries Altovise, a black woman, and this is his wife when he dies. But what people tend to remember are the more publicized relationships he had with white women from a earlier period in time. No one seems to pay much attention at all to the way he sort of spent the last 20 years of his life. Not so spectacular in the same way. And so he’s without a voice until he dies. But more people remember the rumors of Kim Novak or Mai Britt than they remember the last years or last 20 years, or maybe more sedate and not as media friendly. The media wants sensation, and that’s not so sensational.

Interviewer You know, when we were listening to and I was working on the Sinatra doc and we listen to these audio tapes we had that Sinatra and his children, Nancy and team and Frank Junior, they all talk just as much as Sammy worshiped Frank. You know, they were there because they had a falling out, you know, And when he got from Samson to the cocaine.

Todd Boyd: Uh huh.

Interviewer You know, Frank wouldn’t talk to her because, you know. Right. You can drink all you want.

Todd Boyd: But you can do drugs. Right. You know what? They make that you make that point in the doc. When dude was like, Frank Sinatra was really comfortable around bootleggers. Gangsters who were bootleggers, drugs. He didn’t have any connection to that scene at all and looked down on it. Sammy for a time got into the cocaine thing, which is a whole different lifestyle. You know, they had drinkers Sinatra from this old saloon culture, if you will, bootleggers, connections to organized crime. And of course, a big part of the whole Rat Pack’s poor performance had to do with excessive drinking. I mean, that was a joke. That was a running theme of the performances and how much Dean Martin drank and that old bit. Once you get into cocaine. That speaks to a different group of people, different set of images, different associations. It’s darker. It is perhaps hipper when it happens. But then, of course, you know, over the long run, there’s nothing hip about cocaine. Perhaps you don’t realize that when you first start, but you will if you use it long enough. And so when Sammy got into this whole cocaine thing, he’s going in a different direction than Frank Sinatra, who’s very old school, traditional drunk. And so the sort of cultural flip from the drunk to people getting high is really a shift Sammy made for a time that others who he was surrounded by never made. And it was cultural because Hollywood and the music industry and everything in the sixties and seventies, cocaine is as commonplace as Kleenex. Well, Frank Sinatra is out of touch and can’t connect with that. Sammy, for a time at least, is immersed in it.

Interviewer Right. Here we are in 2016. Split is split on the same day as you stand today. In the end, in the American sense of show business, as a performer, as a legend, what is what is he mean? And when you think he means to to. A generation of people who are this familiar with a generation of young white people, the generation of black people, my daughters who are 21 and 16, leaving Sammy Davis White to them today.

Todd Boyd: Well, you know, I think one of the things that happens as you get older, you inevitably look at people who are younger and you reach this conclusion that they don’t know anything. When I was young, I used to hear old people say, oh, you’re young, you don’t know anything. And now I’m saying the same thing about younger people. It’s a sort of a cruel transition when you become the person that you once despised simply because you age. But it’s a good thing to age. So you take that as part of the process. I’m not sure that in contemporary culture, Sammy Davis name resonates so much because he’s really a figure from quite some time ago. If he were around in the nineties, that would be, you know, 20, 20 plus years. But Sammy Davis is last sort of major cultural impact would have been in the early seventies. And so this is over 40 years. So, you know, it depends, I guess if you’re educated and you find out about them, your parents tell you about em or you’ve done some research or, you know, maybe you saw Ocean’s 11, the original. I mean, again, you say Ocean’s 11 now and people think you’re talking about George Clooney and Brad Pitt. They don’t necessarily think about, you know, Peter Lawford and, you know, Dean Martin and the original film from back in the early sixties. So Sammy’s not someone I mean, Frank Sinatra is not that popular now with a contemporary generation. Dean Martin is less popular than both Sinatra and Sammy Davis. But there was a time when Sinatra, Davis and Martin were the most popular entertainers in the country. So, you know, over time, celebrities come and go. We live in an environment now when if you want to go listen to Sammy Davis saying it’s easy to do, you know, that wasn’t the case 20 years ago. Certainly wasn’t the case when he was in his prime. We have access to more culture now than ever, and it’s almost as though we sometimes are overwhelmed and don’t necessarily know what to do with it. I think Sammy Davis is one of the most important entertainers and cultural figures in American history. He was a phenomenal performer. He was a versatile performer. He’s someone who was complicated. There were a lot of contradictions. There were a lot of things about him that were not cool. But when you look at his talents, his body of work, I think you have to respect that. He was a major figure for multiple reasons, not just one thing. He was a great dancer. He was a great singer. He was a great impressionist. He was a complicated black man. In a society where race and culture have always posed certain challenges. He was a friend of Frank Sinatra. He was Frank Sinatra’s sycophant. He was a guy who was dating white celebrities in Hollywood, marrying white women before such things were even legal in all the states in this country. And then at another point, he’s hugging Richard Nixon. You know, one of the worst figures in American history for multiple reasons. You know, when you look at a guy’s life. You look at? What did he contribute? Sammy was controversial. He was prolific. He was profound. He was complicated. There were things about him that would infuriate you. There were other things about you that will make you stand up and applaud him. So when you talk about that, when you have a life and a career like that. The works there. It’s just a matter of whether or not people in contemporary society make the effort to discover it. What he left that works there. You know, you can watch Ocean’s 11, Ocean’s 11. You can, you know, listen to Sammy Davis and Count Basie drum solo. Yeah. Watch him play a drum solo. I mean, you know, the guy could play the drums. He played a trumpet player. I mean, and this is a sort of strange analogy, but maybe speaks to the contemporary aspect of it. I obviously watch and talk about basketball a lot, and when I look at the reigning best player in the NBA as we speak, I would say LeBron James. I just had this conversation before coming up here. I would say LeBron James. And what I think makes LeBron James distinct as a basketball player is his ability to do multiple things on the floor. He’s not the best shooter, but he can shoot. He’s not the best scorer, but he can score, he can rebound the basketball. He’s great at dishing out assists. He can guard the best player on the other team. He provides leadership. Now, other basketball players, Michael Jordan, for instance, you look at his statistics, the statistics were incredible. They jumped off the page at you. LeBron even concentrated in one area. It’s the impact he has across the board in filling up the box score. To me, versatility. Sammy Davis is like a guy who could fill up the box score. Every night. He could give you a real nice line. Some nights it might be his singing, some nights it might be his dancing. Sometimes it might be his acting, sometimes it might be the impersonations, what have you. Sometimes it might just be an appearance. A photo op, but he. He filled up the box score. He could do it all. And when you look at it, it’s almost as though. What is it? The total is more than the sum of its part. That Sammy Davis versatility. Like he could just do so much so well. And it’s not like he was dabbling in these things. He did these things well. Had he focused on any one of them, he probably would have been the best ever. But it’s the cumulative magnitude of his multiple skill set that I think distinguishes him from his entertainment peers.

Interviewer You know, the sixties, we were in Vietnam, you know, heavy, heavy into Vietnam. And one of the men who went on to Vietnam, I mean, besides Bronco, John Wayne went to Vietnam. And everybody knows that John Wayne was in the sixties. Yeah. And Sammy went to Vietnam. And what do you think motivated saying he really wanted to be a good American? Vietnam. Nixon asked him to go and go to the U.S..

Todd Boyd: Well, I think, you know, when you look at Sammy and you look at, you know, the fact that he had been in the war himself, the difference between World War two and Vietnam is the difference in American history from the forties to the sixties. World War Two was generally thought of as the, quote, good war. That’s debatable, but that’s how it’s thought of. That’s what it was referred to. That’s the narrative that has emerged. And so, you know, Joe Louis was in World War Two and he put on boxing exhibitions for the troops, and Sammy was in World War Two as a soldier. And it was this real patriotic thing. By the time you got to the sixties, you had really a split in society. There were some people who felt like, you know, whatever war America is in, you supported, that’s your patriotic duty. And then by this time, however, there were other people who felt like Samuel Johnson. You know, patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel. So by the sixties, there’s a visible protest against the Vietnam War. It’s not cool to be in support of the war. This was a point when Sammy, I think, misread what was going on in society and in some ways is just like him hugging Nixon. He has associated himself with the wrong side and he doesn’t even realize it. And as time passes, this will become more and more evident. So by going to Vietnam, Sammy ended up, you know, cosigning something that people on the left, the student radicals, black power advocates and others really were rejecting. And so it made him, I think, like hugging Nixon and look really out of touch with what was going on in society. I mean, you know, Muhammad Ali refused to go to Vietnam. And so here’s a guy who, you know, he’s not going as a soldier, but Sammy’s like, I will willingly go to this place that people are leaving and going to Canada to avoid. So I think it put him on the wrong side of history, the same way hugging Nixon associated him with a set of politics that ultimately were not the politics he would want to be associated with. But I think in his mind, this was the patriotic thing to do. He had not evolved. It was like he was stuck in that World War two moment, even though society had changed drastically by this point.

Interviewer So it wasn’t Sammy Davis life. Tell us about. America.

Todd Boyd: What is Sammy Davis life? Tell us about.

Interviewer Black in America.

Todd Boyd: Huh? Well, I think it tells us, Sammy Davis life tells us that, one, if you have talents that someone can sell, that you can benefit from the selling of those talents. As Barzani says in The Godfather, after all, we are not communists. So Sammy Davis, a black man growing up in a racist, segregated America, has exceptional talent. That is not something shared amongst the populace. Most people don’t have the talents that Sammy Davis has, the drive that he has, the will that he has, but the talent, you know, will and drive you can develop that you might not be able to sing as good as Sammy Davis. A dance is good, you know. He traded on his talents and he got to be very famous, very visible. He made a lot of money. He made a lot of purchases, spent a lot of money. I mean, he lived a good life for a time and then he died sick and broke. You know, so in some ways, that’s what it is. You know, you have some fun, you make some money, but at the end, you’re broken, you’re sick. It’s kind of unfortunate. And he’s not the only black performer, black celebrity from his era, from his generation to. Go out that way. But I mean, I always call it the gift and the curse. If you have these talents and you can sell them, people will pay you money. But you still live in America. And so how do you develop yourself as an individual to function now that you have all this money? You can give people this money, but what are they going to do with it? You know? So I think his success speaks to the fact that this is capitalism and there’s always a marketplace for people’s talent and ability. The question is, what do you do with that once you’ve cashed in? And is this, as we say now, sustainable? In his case, it was not sustainable. The time at which he was relevant, he was especially relevant. But by the end of his life, he was broke, He was sick and sort of a sad figure. So gift in the curse. The gift was his talent. The curse was being black in America and people and society not always appreciating what that really means.