Speaker OK, we’re rolling. So tell me how you first met Rockwell and started to work with him?

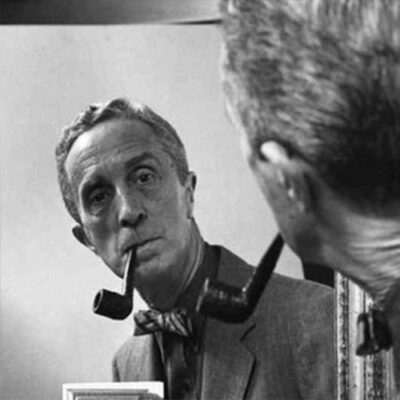

Speaker Well, actually, I first learned it was called by Molly. They ran a little article in a local newspaper when when we bought the house and Molly called me up and said that I was a photographer. And she said, would I be able to brush her up on her photographic techniques? Because she apparently taught photography at the school that she taught at in eastern Massachusetts. And then she wanted me to bring her up to speed on 35 millimeter. The only thing that she’d work with her, Rollie’s the ultimate twin enrollees. And so it seemed fine. I was brand new in town. And so I met Molly and instantly fell in love. And things went on from there. Norman then called me. I don’t remember the first job. Actually, yes, I do. The first job I did was for Norman was to shoot a series of his photo is his paintings up at the Berkshire Museum. They restored a picture museum and he wanted a series of eight 10 transparencies. He was trying to interest Abrams in a book of his. So I met Norman and we shot a few eight by tens and he he liked them. And so that ended up. Oh, about three months of work and shooting all his paintings, which at that time were stored in a vault at the museum.

Speaker Now, how did do you answer.

Speaker Oh, I’m sorry. You. Not not microphones is still of yours. Oh, that’s right.

Speaker Right. Right. Rolling. Showing. Showing. Nervous, Nancy.

Speaker Great. So how did he use photography in his work as a painter? What was the role of the photographer?

Speaker In some ways I began to wonder about that because when I was photographing for him, he was extraordinarily specific and exactly what he wanted. He was very careful in his choice of models. He would. And even when I was shooting inanimate objects like the helmet for the moon walk, he was very specific on exactly how he wanted to left. He was standing here in the studio and I was fiddling with floodlights. That was before the days of Strobe for me. And he was he had absolutely cleanly in his mind what he wanted. And I kind of wondered what why do you want me? I mean, why not go out and paint it? And I don’t really know. But he always used a photograph. And not just of transparency, but he would also use a print always. At the moment, I can’t remember the size because he used a big opaque projector and then he in his back of his studio, the opaque projector, I think it was six and a half by eight or something like that, exact size. They would use the opaque projector projector, the photograph onto the blank canvas that he had guess owed, and he’d sketch it in Terkel and back and like chuckle and then he’d take it out to the studio and work on a painting. But it was sketch. The entire thing was sketched in from a photograph. I I can’t remember a an instance that I happen to know about that that didn’t happen. In other words, that was the way it happened. So far as he was concerned, even though he had a obviously an absolutely clear idea of what the final thing was going to look like. Even I think in this some of his sketches that were often that he would do a somewhat a rough sketch and send that off to whatever publication was going to publish.

Speaker And. But his he had a absolute idea of what he wanted. And he always worked from a photograph.

Speaker Well, I mean, mine are.

Speaker What is it like in the way where I mean, it was kind of like a movie director I was seeing and he was like creating an image. Right. Really? Literally creating.

Speaker I have not worked with that many movie directors, but it seems to me that he probably had a much better idea of what he wanted than a lot of movie directors that I’ve seen their product up in that he really did know.

Speaker There was nothing left to chance. He had the idea ahead of time. And then all my role was to come in and record the realism. The real thing, which he would then rerecord as a painting. If I understand your question, right?

Speaker That’s right. I mean, some people might accuse them of lack of imagination, I guess.

Speaker He often accused himself of that part of being noncreative. Just start over. Like it’s never there in my classroom.

Speaker Rephrase it.

Speaker Well, my question was, you know, some people would accuse them of lack of imagination.

Speaker Yes, he in some cases was accused of lacking imagination. And he himself said he’d never called himself an artist. He always called himself an illustrator. He’d never refuse to be called an artist. I have heard him correct people who have called him an artist. I don’t remember. He gave a talk somewhere. I can’t quite remember where in Pittsfield. And he was introduced as the great artist Norman Rockwell. And the first thing you said that he was not an artist, that he was he was an illustrator of how exactly he made the differentiation. I’m not too sure.

Speaker But he was very, very specific and.

Speaker Every now and then, he would say that well known and I’m bright, very creative. But it was not a he did not. Sorry. OK.

Speaker You think of photography using photography changed his work. Because in his early work, he didn’t use photography.

Speaker That’s an interesting question, and I’m afraid you’re going to have to talk to someone else because remember that I came in at the end of his career. That. And looking at another word, I’m not a student or a I haven’t studied his early work. Other than photographing had up there, and when you’re doing that, you don’t really see it. You know, you’re worried far more about too many highlights off the brush strokes, etc, etc.. So.

Speaker Did photography change his work?

Speaker I don’t think so, because, well, I’m going to I’m going to pass on that really, because I really don’t know. The early work, such as the.

Speaker I think that the one of the clowns and the little dog.

Speaker I mean, to me, when I was photographing, it occurred to me it had maybe because I identified with clowns, I had more sort of more life. Now we know that was done without photography. And I think that rather famous, one of the salesmen, the traveling salesman in the hotel bed with all the bugs. I think that that was also pre photography, painting. Other other than that, I can’t I can’t say I’m not I’m not a student of his stuff. I haven’t done the things that I worked with him on. I know pretty well. But the rest of it, I’m not. I don’t. I remember that from my childhood on the cover of collieries.

Speaker I don’t know. Some people remarked that his work and letters especially echoed in photography in the sense that you could see different focal length of lenses, for example.

Speaker Oh, I think in that way he was influenced. So yes, it does then what life is. I think that that his use he began to use.

Speaker Yes. Not focal length of lenses. But he began to use the different. He would ask for a wide lens and a couple of cases very specifically wanting.

Speaker I’m trying to remember wanting a very definite foreground background. I remember the photograph we did for him, I think was one of the ones we did for really was different. That book of Marling’s that there was a foreground of flowers and things, and he wanted that and absolutely wanted one of them in the same photograph.

Speaker And he certainly knew enough about it to ask for a wide lens on that particular shot. And so from that point of view, yes, I think it did.

Speaker But other than that, I don’t I don’t know. I don’t I don’t I don’t really know.

Speaker Tell me about how he worked with models and let people know very again, very specific with me. He or he ordered me around because I was I was on payroll, you might say. He was very specific about how a model would stand. I remember in Chicago that he would look at the scene from near the camera and look at it and then the Russian and and said, no push. Bring in your back like that. And then come back and look at it. Never looked into camera. Absolute rule one. Never looked through a camera, but he would come back and stand right beside the camera and look at it very carefully.

Speaker And I think we’re gonna have to do something about the phone. Yeah.

Speaker Yes. So I’m just briefly to summarize. So do you think he enjoyed working with models or was it just sort of part of the process?

Speaker I think was part of the process. I think he actually he enjoyed doing the painting. He enjoyed the painting. As Molly said, he was a workaholic. I mean, in some cases, he’d be out there very, very early in the morning. That idea that suddenly struck him or something? Yes, I think he enjoyed working with the models. I think that it sort of it became more real to him, I would think.

Speaker He was also very good with the models. He was never he never was dictatorial at all. It was very specific about what they were to to do and what to what. And he was very specific about what the painting was, what the idea of the painting was. He would explain it to them very carefully so that so that they were almost more actors than models. They had an idea of what what the final result was supposed to be. And I think that they universally, from the people that I have spoken to in course, the town is full of people that have been models for Norman Rockwell. They all enjoyed the experience. It was it was an exciting and different.

Speaker And they enjoyed him because he was an extraordinary, personable fellow and very nice, very intelligent and just a nice guy, sort of. He put out very few negative paintings, you might remember. And it was a very pleasant experience that way.

Speaker I think he was kind of an actor himself.

Speaker Some people say, oh, yes, yes, yes, very dramatic. And I enjoyed it.

Speaker Very self-confident in that way and enjoyed his enjoyed his role of being Norman Rockwell.

Speaker I mean, he worked very hard for it. I mean, this was this was a long ways for a little kid from New York, you know, and.

Speaker And he had a full confidence the other night. Nice thing about him. He was not falsely modest here.

Speaker He he knew he was good at what he was doing and enjoyed enjoyed what he was doing. And didn’t.

Speaker Think that he thought he was pretty good about without being without appearing egotistical. I think that that’s a good way. Was he the same person that was his public image from. Oh, yeah. Yeah. I don’t think he was an actor in that way. I’m sorry nobody heard the question. So if you could just. Oh, he was.

Speaker He was. He was not an actor in a sitting at the dinner table.

Speaker He was the same person as giving a talk or talking to the models or talking to his public as such. As I say, a very intelligent and very.

Speaker Up to the minute, I guess we put it that way, they kept track of the news. I’d remember he and Molly used to sit at the breakfast table and they each had one of these wire newspaper holders and they’d sit there at the breakfast table over at the house and reading a newspaper every morning over breakfast. And he was very up and current with current events. I have a hunch that Molly influenced that to a certain extent.

Speaker But yes, I was going to ask if she changed him or how she changed him.

Speaker Oh, I think she changed him dramatically. I think that. Well, not just me, old friend of his, not Horwitt, the inventor of the museum. Watch, you know, the Movado, the inventor, the designer who was a who was a successful New York designer who lives in I lived in Lenox. And he made the remark that thank goodness Molly made him a liberal. And because I don’t know if he had any particular political affiliations before, but Molly came in and really he did become a liberal as soon after that, that he did the the Mississippi painting. And I think you can see a change in his paintings, pre Molly and Postmodern.

Speaker Yeah, I’ve heard she likes she stopped them from doing some things. So, like, I was not privy to that.

Speaker I don’t know that that may may well be. He may have come up with an idea. One thing, he was very articulate about his ideas and he was very open to other people’s ideas.

Speaker Someone would come up with an idea for a for a new cover for Collier’s or poster or something, and they would call him up and chatter on about it. And he would say, no, no, no, I didn’t like that.

Speaker Or that’s an interesting idea. Why, why? Why do we think about that? And so from that point of view, are these paintings did not all come out of his head once. He was. Once he had the idea and was going on it, then I think it became very specific because the specificity would set in.

Speaker But before that, he was very open to other people’s ideas for an illustration or a cover or whatever. Some of them are perfectly obvious. I think that the moon shot paintings were fairly obvious. It’s forget.

Speaker The same yourself about to tell me something about the moon shot.

Speaker Well, they were a fairly obvious idea that moonshots paintings were fairly obvious, too, in creative creating them.

Speaker The.

Speaker The other thing is that he was, as I say, that he was open to everybody’s ideas. I have a funny hunch that his the other photographer that worked with him for many more years than I did, Mr. Lemmon, was almost his sort of his common man because they would stand and discuss the painting as it was progressing, which is something I never did.

Speaker But far be it for me, although I.

Speaker But Louis had known him for a great deal longer than I had.

Speaker And.

Speaker So I think that, as I say, he was open to everybody, everybody’s ideas, once he had once it was set in his mind of what it was going to be, then it was pretty well set in concrete.

Speaker Was he a little bit insecure about his work, you saying?

Speaker No, I don’t think so. I don’t think so. But he just like. Input.

Speaker He’d like input, particularly for for originating ideas from what? I see that from my observation, he enjoyed the other people’s input. Let’s put it that way. I’m not I can’t say for sure, but that from my observation, it seems. It seems. Think so.

Speaker Tell me about some of the paintings you worked on. You. Like spring flower, still life.

Speaker Well, the spring flowers, they’re still lifes.

Speaker And I did a great deal of the Willie was Different Book of Mice and, oh, the Chicago Art Institute.

Speaker We went to Chicago, the I did.

Speaker Oh, a series of things. A small model. Things of.

Speaker The movie, the movie, the movie Stagecoach Stagecoach. Matter of fact, it was in Chicago. They were just they were going down a street and he suddenly stopped in front of this store that had a model of a stagecoach who’s about. Yard long, I guess. Very, very detailed model of a stagecoach. And he stopped and went in and bought it on the spot. I have no idea what he paid for it. Considerable amount. I would imagine, because he said, you know, I’ve been trying to figure out where to find a state coach. And I’m pretty creative, but I couldn’t figure a stagecoach. So he bought the model and I ended up photographing the model and nerves and. And also some of the some of the models, some of the actors that were here. Otherwise, they all came out of Hollywood headshots for those.

Speaker What about Picasso versus Sargent? Oh, well, that’s the short answer to that. Was it in Chicago that was done? There was. I’m sorry.

Speaker The painting, the painting.

Speaker The painting was a the a young teenager standing facing directly away from the viewer, looking at a Picasso or dripping drool type of painting and which, by the way, Norman had great fun in creating. And then and then the parents, middle aged parents looking at a I don’t remember what the what the other painting was, but it was very straightforward painting. And far as he was concerned, it had to be shot in Chicago and he was very happy to have done so because the flaw in that particular gallery he hadn’t pictured in his mind. And so and we went through in a day. Oh, must have been 10, 12 sets of models and finished little early. And that’s another thing. He discovered it was we were done a little early and we could then we could possibly get a little slightly earlier flight out out of Chicago. And so we got myself all packed up and we rushed out. And when he found out, I found a taxi and he’s told the taxi driver who recognized him instantly. Can you get us to, what is it, O’Hare in such by such and such a time?

Speaker And he said, well, you better worth my while. And I then had one of the most terrifying rides of my existence, just absolutely terrifying.

Speaker Down the back alleys and out across streets with no no pauses. You know, matter of fact, we got to O’Hare type to have another drink. And at that time I needed it. But Norman was perfectly cool about it.

Speaker He sort of sat back and watched the scenery going by, but and he didn’t seem to have that imagination. It. We were about to be wiped out. But it was it was fine for us. He was concerned. We got there in time.

Speaker Did he ever talk to you about his feelings about modern art? No.

Speaker No. Other than that other than the fact that he was he had great fun in in creating this grip and rule for painting. That was then shipped to Chicago and hung on a wall to set up for him. But he had great fun making that. He did that several different times. He said he tried throwing paint at it and and dripping paint on it. There’s only one and only modern painting. I don’t know where it is at the moment that I hope that the museum has it will display it every now and then because it was a full size drip and real painting.

Speaker It’s quite fun.

Speaker A little bit more about his life here in Stockbridge, like his relationship to Erick Erickson.

Speaker Oh, well, his relationship with Eric and Joan, for that matter. And and Riggs, I assume, as you’ve talked about that before he did, that the reason he came to Stockbridge was it was Riggs, both for himself and and for his camp.

Speaker I don’t remember his wife’s name. Mary. Mary.

Speaker Is it okay because of because of Mary and and his he had a long, long term relationship with race. And matter of fact, I had the honor he used to pay for some of the fees with charcoal portraits of the various doctors, Eric, among them.

Speaker Matter of fact, Eric’s behind you on the wall and.

Speaker And then I I took photographs when when they when the portraits became, as the years went on, became more and more valuable, they decided they didn’t want them hanging on the wall anymore and put them in a vault. So I made photographic copies of them. Those are what are on the wall now.

Speaker What was his relationship to Ericsson? Thankfully. I think.

Speaker Well, a friendship and and and patient.

Speaker Dr. Relationship and again, Erixon, while Erixon, again, extraordinarily intelligent and very personable. And I think the two men got along very well. I never frankly, I never saw them together as such. I know.

Speaker I’ve seen. Yes, with Joan. I remember some long conversation because Joan used to spend some time here. They were close personal friends of ours. And at that time, I was teaching over the lavender door, which is a the craft branch of rigs that Joan. I think Joan basically started. And before before our arrival, we’d been in town since 65. So, Chief, they were here well before that.

Speaker But I mean, it is a little country to Rocko’s Public Image. I think probably a lot of Americans would be surprised. And now.

Speaker Well, I. Oh, I see. I think.

Speaker I don’t know. I don’t know how to put that. I don’t. I don’t know where I’m treading on unknown ground here because he’s certainly there was no outward sign of any mental upset, although I have a feeling just in noticing that there were certainly mood swings that there might have been. I don’t I don’t know what the problem was. Possibly some manic, possibly some depression. I don’t know. I think also it just ended up with to a very, very intelligent man in approximately the same age bracket enjoying talking. I think that that had a lot to do with it also. Certainly.

Speaker Certainly it was, Mary, that the reason that they came to town from Vermont.

Speaker I think that’s certainly Rockwell was a little more intellectual than people might think.

Speaker Oh, yes. Yes, yes. In other words, he was very much more. Well, not. Yes, he was an intellectual. Let’s put it that way. And a great deal of thought went into paintings. And as I say, he was an omnivorous reader and did not like the radio.

Speaker I asked him once why he didn’t have the radio on. Didn’t like the radio. So and I I don’t know his his attitude towards this medium.

Speaker I don’t know what to tell it with. Television was important at all. I really don’t know. We went to dinner there several times and they came to dinner here several times, but we weren’t. And I really I knew Molly as a person far more than I knew Norman as a person. And I think Norman was a far more. Guarded. A human being. Far other than in his work.

Speaker He was less. Outgoing then then Molly.

Speaker At least during the period that I knew it was your impression of how a gang related to the kids, the children like his kids.

Speaker Yeah. Oh. Distant.

Speaker I think. I only know Jarvis is the only one I know well.

Speaker Jarvis. And then. I knew.

Speaker The other son, he’s in Italy. I can’t remember his name at the moment. Knew him for one summer. He was here at the corner house for a summer and he seemed to have a very easy relationship. Jarvis was well, as I said, I don’t know that I mentioned. I remember Jarvis at the Virtual Theater Festival. I used to be active there and he Jarvis came in one afternoon just before one play and.

Speaker Mightily, that his father’s passion for authenticity had finally gone too far. That he was going to he had to get be there to get a bottle of blood. This was for the. The Mississippi painting that he had to have real blood. And Jarvis was not too happy with that. And so but in his relationship with the kids, I am, too. We came too late for me to observe that specifically.

Speaker Kids seem to survive. So.

Speaker Did you know Rock, were you close to him in his later years? Did he do what? Were you close to Rockwell or around him at all? You know, in the end of his life?

Speaker Not really.

Speaker He was he was not very active and only to the point of, you know, high. And I was active with him on the.

Speaker We had a a Norman Rockwell day here and in Stockbridge, I guess about a year before he died, I think. And I photograph that for him. And he was he was very happy with that.

Speaker Well, he’d slow down, as we all do. You know. No, I was not that intimate with him that I was there, you know, during the last. The last time Molly, of course, was there.

Speaker How what was the reaction in the town here when they died?

Speaker Sadness. Very definite. He was well liked. He was very well liked. Not as a he was well liked.

Speaker Not for being Norman Rockwell, but, well, like for being Norman, you know.

Speaker He I mean, he was very, very easy, particularly during the winter when we’re not inundated with outsiders and our town population goes back down to its normal size. I mean, he was in and out of the grocery store and went down for a bottle of milk and he was just a member of the community and was was accepted as such. In that way, the town is.

Speaker Is very good about that.

Speaker Yo, yo, my friend for several years had the house right next door to us here and he touched down to the local grocery store for the morning milk and me. And the town doesn’t. The town regulars don’t seem to think think about it. So from that point of view, well, there are a lot of fairly famous people in town, writers and this and that. So this is a very easy town for for Norman to be Norman Rockwell in.

Speaker So you have a favorite Rockwell painting.

Speaker Oh.

Speaker I think. Well, I have to actually, one I had nothing to do with. I have always enjoyed the traveling salesman, that early traveling salesman painting, and I enjoy the moon series because I was very closely involved with that.

Speaker If I like the.

Speaker Well, I kept track of the of the Apollo missions and all of that as something goes, my heavy duty interest. And so, yes, I have enjoyed that and enjoyed being involved with the with some of the photography for it. The helmet and the and the boots. The boots are silicone rubber, which was another client of mine over in Waterford, New York. That’s made over there. And so having the idea of the boot that I had here in this studio, being one of the first ones to put a footprint on the Moon River, I felt good about that.

Speaker So that whole series I’ve felt I’ve enjoyed doing a Rockwell painting, The Real America or kind of a dream of American.

Speaker Whoo! That’s a hard one. I think I think at the beginning of his career, from the things that I can remember, I think it was a dream situation or a little slice of. What we like to consider the better part of America. I think you began as as he became of more of a liberal thinking or political person, I think.

Speaker Well, certainly the Mississippi painting and the fact that I think is very interesting is the fact that he allowed where was that collieries?

Speaker I think he allowed Colliers to publish the first sketch of the of the idea of the painting rather than the finished painting. I actually think it was look to mine what maybe is.

Speaker Look, I don’t quite remember, but he allowed it. He allowed them to because apparently he had been requested had that request before. But four other sketches and that was a no no so far as he was concerned. But he agreed that he’d been a lot matter when he did the sketch, then when he when he went ahead did the finished painting. And both of them, I think they’re side by side over at the at the at the museum.

Speaker And it’s a very interesting comparison of paintings.

Speaker Right, let’s cut Pam. OK, so just tell me that story.

Speaker Oh, well, that this is sort of a follow up on a whole Chicago Art Institute painting that he was never really happy with the young the young lady, the teenager. Not really happy. None of the models that he saw were exactly what he had in mind.

Speaker And at that time, there was a the Marching and Chowder Society, which was a group of men, usually mostly my senior, that had luncheon. I think it was Wednesday’s over in South South Lee. And so I was invited one day to come come along. And another close friend of mine, Jerry Hatch, was going to pick pick me up and Norman up. And so Jerry showed up in his old farm pickup truck. And so we piled in. And Norman was sitting in the middle. And I was sitting on the outside. And we were vogeler going over the hill to a rough road at that time and even rougher truck. And. And we went down the hill into West Stockbridge, into South Philly.

Speaker And this this young lady walking along the sidewalk. And Norman, look, he said, oh, my God, look at that ass and stop it. So while Jerry jury came to a screaming stop in Norman, I piled out. Norman piled out. And he went running down the street. And the next day, the young lady was in a studio being photographed. Does she? I think he told her why. I mean, it was just that the particulars. She wasn’t malformed. She wasn’t overweight. But it was just exactly what he wanted. Long blond hair.

Speaker So that was fun.

Speaker But it was great fun. And he had no.

Speaker He wouldn’t shy about asking people to come to his studio with if they would. I mean, certainly he paid them well and and usually everyone would be very happy to be in one of Norman Norman’s paintings. So that was kind of fun. Oh, my God.

Speaker Look at that ass.