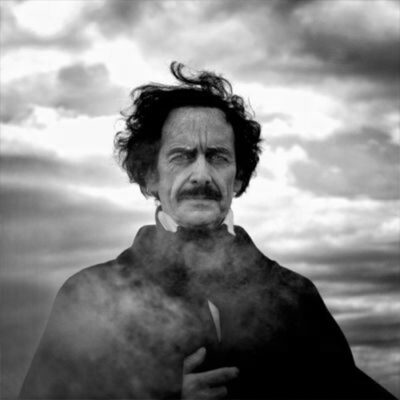

Speaker In September of 1849, Poe arrives in Baltimore from Richmond. He’s 40 years old and he’s been complaining of headaches, of not feeling well at all.

Speaker And since we’re on the topic, I’m going to. So who was Edgar Allan Poe in 1849?

Speaker In 1849? He’s at the height of his fame. He had just collected the money he needed to start his dream, his magazine that he had been pining for for decades. The. He called it and he was about to be remarried. And so his death at 40 years old is a travesty. And in many ways, not just for American literature to think of what he did not produce because of his early death, but also a personal travesty. I think he was about to be happy probably for the first time in his life.

Speaker That’s great. So what is it that makes Poe unique?

Speaker He invented the detective story, actually.

Speaker Do you mind starting with saying there are ways in which Poe is unique just because we don’t hear requests? Yeah, of course. Of course.

Speaker Here’s what makes Poe special. He invented the detective story. He was the most potent influence on the suspense story, the horror story, the adventure story. He makes Freud look somewhat beside the point. He furthers our understanding of Kafka. He is, I think, with Nietzsche, the dark prophet of modernity. Without Poe, you don’t have a constant understanding of American literature, which you also don’t have a constant understanding of the calamities that were about to befall the 20th century.

Speaker Let me ask you more about that, so because we’ve had other people talk about polls, a precursor of modernity, but, you know, for the sort of general audience, that doesn’t mean a whole lot. Could you sort of pass it out a little? Like what does that mean? What did he do that other people were not doing at the time? And what did he presage?

Speaker Well, with with 20th century literature, the moderns especially comes a dismantling of ways of perceiving. And literature reflects reality. In many ways. You can measure you can gauge the climate of the culture by its literature. And what we were going to see in the 20th century after the tremendous calamity of the First World War was a breaking down of of order, was a breaking down of everything we thought we understood about human living and about spirituality and about the dark side. Well, the pope was going there 60, 65 years or so before the First World War. But when you look at Poe’s contemporaries and what they were writing, he makes them seem all a little bit childish and gossamer. He was absolutely unafraid, I think, of new ways of seeing of embracing the darkness. Now, after the First World War, this became this is what you what you did. I mean, the poetry, especially prior to the First World War, you look at Wilfred Owen, for example, and you see a way of comprehending a way of ascertaining human living and human destruction in a way that you simply hadn’t seen before. And you see hints of this appearing in Poe in the 30s in the 1940s. And so it’s it’s tremendous. I think I think Poe has this reputation as a dark prophet of modernity precisely because of his fearlessness.

Speaker And this, I think, has to do with Longfellow as well. And I could I could sort of segway into Longfellow.

Speaker I was about to do that, but I wanted to stop because our films chronologically, of course, are we doing the Longfellow war when it happened in 1945, damsels that were down or anything, but just the lingering impact of the reading, do I mean ask a question? Yeah, sure. So why at the height of his fame, his success did launch this war against Longfellow and who who won in the end? You know, what what was it about and who was right?

Speaker There’s something maniacal, hysterical in prose, repeated strafing against Longfellow, something self-destructive, what Poe calls in another context, the of the perverse that force inside of us that compels us to our own doom.

Speaker I’m sorry to have to rely on the basest motive, but oftentimes the basis motive is the truest. He was jealous.

Speaker He was envious of Longfellow.

Speaker You’ve got to keep in mind that at this time, Longfellow was not only the most well-known of American poets, but he was the most beloved in New England especially. He was the first American poet to be able to make a living from his poetry. He was a savvy businessman in a way that never could be. He had a plush professorship at Harvard. He married into tremendous wealth. His wedding present from from his father in law was a large, lavish home. Meanwhile, Poe is living in a shack with his mother in law and his sickly cousin bride borrowing money with both hands. Breadcrumb poor all along, writing work that had a fearlessness and. A vision and an insight that Longfellow could not touch. And so in addition to the jealousy and envy, which, let’s be honest, most writers feel of other writers, there was this powerful sense of injustice. What is going on here? I am the more talented writer, and this guy is being lauded. This guy has the riches. It was called the Longfellow war, but it wasn’t a war in any sense. Longfellow, magnanimous as ever. He was, by all accounts, an upstanding individual, very generous. Longfellow never fired a single shot. In return, he never published a reply to pose onslaught against his reputation. I’ve got to say that that was the smart thing to do. I think it was the dignified thing to do. But if we insist on referring to this as a war, Longfellow won that war in the 19th century, but Poe won it in the 20th century. And he continues to win it in our own day because nobody reads Longfellow anymore and everybody reads Poe.

Speaker Thank you. That was good, right? Yeah, that’s great. Could you explain very you know, and again, like the way I the way I describe a PBS audience, a smart eighth graders. Yeah, OK. You know, even though they’re mostly adults, their brain is working at about the level of a smart eighth grade when they’re watching TV, because that’s what TV does, too. So. So can you explain what he meant when he wrote about the heresy of the didactic and how that fits into that context that that Poe thought Longfellow and the other New England writers were you know, they were political, they were didactic, whatever. Yeah.

Speaker So post conception of Longfellow’s faults, in addition to the transcendentalists, that he had no patience for this idea of the heresy of the didactic. In other words, my art is going to entertain you, but also teach you something, a valuable lesson and whether it’s political or moral or what have you. And Paul was having none of that. He didn’t believe in the didacticism of art. He believed that art existed for the sake of its own potency, that it was not to teach a lesson. It was not to inculcate morals or values in this, I think is what so offended him about, about Longfellow in addition to everything else.

Speaker This idea that here was the most famous poet in America and he was essentially a glorified schoolteacher trying to show you the right way and how to be a good, let’s be honest, how to be a good Christian citizen. And Pahad simply know no patience for that. I think it was I think he was disgusted by it. I think it was offended by it. And the injustice of it. The the fame and the wealth that came to Longfellow as he suffered in obscurity, I think was for him much too much to take.

Speaker Thank you. Since we’re sort of in that neighborhood time wise, you talked about how he was living in Fordham in the Bronx. You do know enough to describe kind of what that scene was like. Have you ever seen that cottage, you know, still exists?

Speaker It doesn’t look too much as it did then. But tell me if it was as remote as I imagine it.

Speaker It was in the middle of orchards and fields. There was another big house nearby, but not that close. Interestingly, what’s now Fordham University was nearby was then, I think, St. John’s or something. And Paul would go play cards with the monks. They all loved them.

Speaker Nice because he knew so much. Yeah, he’s such a good conversation, of course. But it was really sad scene at home. Yeah. I didn’t have money for no wood or coal and Virginia was coughing up blood every day using post coat for a black coat as military. I’m going to keep you informed.

Speaker Well, tell me tell me what you’d like me to say about that.

Speaker I’m happy to say anything about how pathetically sad it was that here he was trying to nurse his dying wife with not a cent to his name, trying to make money writing, but meanwhile, Virginia coughing away in the next room.

Speaker I also imagine it as a shack, Eric. I mean, is it fair to say that or would you like me to say cottage, farm, cottage?

Speaker OK, it was very, very rustic.

Speaker So we have to imagine this tremendously sad scene at this farm cottage in Fortum, New York. They didn’t have money for heat. They hardly had enough to eat.

Speaker The winters were where unforgiving Virginia is coughing up blood, trying to keep yourself warm with Poe’s military coat and the family cat.

Speaker We have to imagine the tremendous despair of this scene. It must it must have been, I think, almost beyond what Poe felt he could endure. And if you look at his letters, he’s full of declarations of I cannot endure, I cannot endure. And you never quite know how hyperbolic he’s being. A lot of those pleas went to John Allen. And there’s a sense, especially in those letters in the 1930s, that he’s trying to get money and and to win still. To win the affection and the love of this man who neglected him and abandoned him, but I think that that the scene of Virginia dying in this form cottage in Fort of New York is as genuinely despairing as it’s possible to get. He loved her. He loved her dearly. I think he saw in her a kind of resurrection of his mother, Eliza Poe. Virginia had her middle name was the same name as as his mother, Eliza.

Speaker And so I think that what we see happening in that cottage is what we see happening throughout Poe’s work and throughout his life, which is the constant haunting by his mother. We have to, I think, imagine this two year old boy, he’s almost three.

Speaker His 24 year old mother is dying of tuberculosis. He’s been abandoned by David OPO, his father. We don’t know where he went, probably to New York, probably drank himself to death.

Speaker And we have this this little boy, profoundly sensitive, a boy who was born with darkness in his strand’s already.

Speaker And this woman is everything to him. And he’s there at her bedside and he’s holding her hand and she disappears. How does a boy such as Poe ever get over that? He does it. How is he ever whole again? He’s not the death of his mother.

Speaker The death of his mother was a lifelong devastation.

Speaker And he was never able to escape it, not in his dreams, not in his life, and I think that’s what it’s part of, what makes Virginia’s death much more cataclysmic than it would have been otherwise.

Speaker Mudie Klam, his mother in law, his aunt, would often hear him leave the house at night and his stockinged feet in the unholy February cold to walk across the farm and the patch of woods to her grave in the middle of the night to sit there and lament.

Speaker And Poe has this reputation, I think, of being hyperbolically romantic, whether it was in his dress or whether it was in his conception of himself.

Speaker I don’t think there was anything romantic or posing about those midnight sojourns to Virginia’s grave. I think that he was at the lowest point of his life and he he missed her tremendously.

Speaker It was great. Thank you. You know, near the near that cottage was this new aqueduct, the high bridge, which still exists. Have you seen it? Not. It’s it’s this giant aqueduct bridge that takes water from the Croton Aqueduct in Westchester to New York City and had just been completed right around the time. And everybody and they moved into the cottage. And people love to walk on that bridge. You would do that and even before Virginia died. But afterwards and you can’t help. I mean, on the end of the perverse way he talks about that and who hasn’t looked over the edge and wanted to jump, you feel the need to jump in and just imagine them up there. Would you mind just talking a bit about how, you know, there was this aqueduct, this high bridge, they call it the high bridge near is near the cottage and people would take walks there and God knows what he thought about.

Speaker But do you see perhaps some suicidal ideations in that? I do, yeah. I mean, I think OK, certainly after writing this post. OK, so.

Speaker Near the Fordham College, near the Fordham Cottage was an aqueduct, and after posed after, you have to edit that to start over.

Speaker OK, so do you want to say when the aqueduct was built or was close to the college, you know how high the hybrid, you know, a hybrid.

Speaker OK, so because it was a giant span that OK, that had a walkway OK, so near the Fordham farm cottage was an aqueduct.

Speaker They called it the high bridge.

Speaker And after Virginia’s death, Poe would take walks along this aqueduct, pausing there to look down over its edge. And we could imagine what was going on through his tormented mind on top of that high bridge.

Speaker You know, in an essay on Poe, E.L. Doctorow argues that Poe quite enjoyed his melancholy, that he found it useful. I think that goes quite a bit out of its way to misunderstand the nature of melancholy.

Speaker No one enjoys melancholy prose.

Speaker Post depression was the the bane of his of his life. You can see it in letters. You see it manifest in stories. This can’t be overlooked. And what must he have been thinking of on the top of that, Highbridge, as he as he walked across that aqueduct?

Speaker And how many times before had he considered giving up? When you look at his history, it’s something of a miracle that he didn’t.

Speaker When you look at the long list of important writers and artists who have self destructed for a lot less. I’ve got to say, it’s something it’s something of a miracle that he lasted to 40. But I can say that his melancholy was no pose. It was no affectation. It was real.

Speaker It drips everywhere in his work and in his letters.

Speaker He has that beautiful poem in which he says, and what always hits my ears as a Wordsworthian tenor from Childhood’s Hour, I have not been as others were. I have not seen as others saw.

Speaker Well, he was right about that.

Speaker It’s. So talking about the analysts, so living with the Allens who never quite took them in. Can you talk about that a little? So hang on one second. Let’s just let loose. Yeah, but keeping it in that in those years, you know, 12, 13, 14, 15, like what you know is what kind of kid is and what’s he feeling the lack of OK, what’s it like with you know, and so 12, 13, 13, 14 years old is living with the Allens.

Speaker And what we see in those years is someone who is striving desperately for the affection of this father figure. Francis Allen is a not bad mother, yet he was adopted by her prompting mostly. I think that she was pretty good to him. I don’t think Po ever felt that she was good enough. But his main antagonist, I think not only in those early years of adolescence, but right throughout his 20s is John Allen. And I think every boy is looking for the approbation of his father. Every boy wants to be accepted, wants to be loved, but especially for PO especially, this is of the utmost importance. And John Allen was almost. Deliberate in his refusal of that, he seems almost to have gone out of his way not to give this boy the the love and the care that he must have known he needed. I think John Allen was a bad man, and I think he didn’t deserve it. I think that his entreaties posed entreaties to John Allen went on much longer than they should have.

Speaker West Point.

Speaker All of that, but here’s a a young a young man who wants to be something, wants to make something of himself. And why is that? What is he what is he yearning for, really? Why does he want to be a success? Well, you could say, well, everyone wants to be a success. Well. So especially and he wants to impress this man because he thinks by impressing him that he will earn the love that he’s been denied his entire life. I think we see here in these early years of adolescence, the beginning of his ambitions for literature to start a magazine, what was West Point and his brief and failed military career all about?

Speaker What was that about, if not trying to prove his masculinity, to prove his manhood to this father figure who was excessively masculine in his conception of hardship and of suffering, that suffering was somehow character building, that it was somehow redemptive. It is not suffering is suffering. Pain is pain.

Speaker Always is inflicting it upon Poe through not through. That neglect was a sin, I think a real sin.

Speaker If we could get a little more on that, there’s a moment in our film where Po Danos, our character, reads a letter that he wrote to John Allen while he was at the University of Virginia. As you know, he was only there for, what, six months or so. But it’s such a sad letter. He’s saying to John Allen, because I’m worried about the exams, I think I’ll do well. I’ve been working so hard. I’ve been studying so hard. Perhaps if you come visit, you could see some of this. I mean, could you just set that up for us? As you know, when he got to the University of Virginia, he was still so obviously desperate for that approval.

Speaker So when Poe gets to the University of Virginia, he lasts only six months there. But he writes this desperate letter to John Allen in which he’s essentially pleading for his stepfather to come visit him.

Speaker He’s worried about doing well on his exams. He’s worried about fitting in. He’s worried about money. You feel that things are falling apart.

Speaker And there’s this plea. If only you come visit me, it might make everything OK. And he never went.

Speaker That’s great. Thank you. That’s one of the big questions, I’m happy to do it.

Speaker I don’t know how I’m doing. I mean, I think you’re doing great. Very self-conscious. But now you’re doing OK. Fantastic.

Speaker So in eighteen thirty four, John Allen dies, and by the way, we’re always referring to John Allen as foster father since he never legally adopted, they didn’t adopt him, but it was more sort of a foster family situation. You know, mind just using the foster father, Sean? Yeah, but can you talk about the just talk about the fact that John Allen died in 1834 and left nothing left as illegitimate children, something that didn’t leave.

Speaker I mean, so his foster father, Father John Allen, dies in eighteen thirty four and the will leaves po nothing. The illegitimate children get things.

Speaker The child whom he helped raised gets nothing.

Speaker Not surprising. Not surprising. I, I you can read letters about this Paul writing about this and there’s an element of acceptance in this. It’s almost as if Poe was not shocked about this. He almost saw it coming. And if you know anything about this man, John Allen, you’re not shocked either.

Speaker Unbelievable leaves of nothing. And what did it do to her?

Speaker Well, this is 18 34, right? So he’s in he’s in New York, Baltimore.

Speaker He’s involved. He’s come back to Baltimore to you know, he’s living he’s moved in with money and wiring money, but she hasn’t married.

Speaker And John dies in Richmond. Right. Tell me what he does after that. Does he does he go to the funeral?

Speaker No, there’s no record that he actually went to John Allen’s funeral. I think it just was sort of this. It was it was this last rupture with that life that he had been brought up in. Tell me what you think I can recall.

Speaker I can recall this episode, and I don’t remember exactly to whom Poe was writing this to us. But there there seems to have been some element of resignation to that. Do you see that? I mean, you, Eric, do you see that as as did this push him over an edge? Do you feel that this was. Tell me tell me your take on.

Speaker I think it was I mean, he was always one for a bit of delusion.

Speaker I mean, I you know, I know I think you’re right that he he will say that in 1834 after we’re going, oh, I just want to run this by you. So anything in 1834 after Foer realizes that John Allen loves him? Nothing, this is his realization that maybe I should just say, OK, all right. All right. In 1834, when Poe realizes that John Allen has left him nothing, this is his moment of realization that the life he had been dreaming of was not going to happen, that he was on his own, that he was going to have to make his living by writing. He had Virginia to support. He had money to support, and he could no longer hold on to those hopes that anything at all was coming from the estate of John Allen. And it was then that he took a job at the Southern Literary Messenger and moved the family from Baltimore to Richmond with no no ties at all to the Allen family. Popo was cut loose.

Speaker I was out. That was good, although maybe do it again because he didn’t move the family there at first on his own. Yeah, that’s right. And he was you know, he had his first job. He had his first real salary, but he was miserable. Did they come after? Well, they can, but only after he pleaded with them because a rich cousin named Nelson Po wanted to raise Virginia and power of this just heart rending, tears stained letter saying, you know, don’t don’t leave me. Don’t desert to Richmond. Yes. And that’s when he marries Virginia to seal the deal. OK, so maybe it just.

Speaker Yeah, absolutely. So to Richmond alone. Do you want me to make that? You want me to even go as far as the Southern Literary Messenger after he recognizes that he’s going to have to make his living?

Speaker Why don’t you just stick with he realizes he’s going to have to count on his brains.

Speaker OK, got you. Got you. So in 1834, after Poe recognizes that he was left, nothing in the will of John Allen. This is his moment of realization, the life that he had been hoping for, the life that he had foreseen for himself, money from John Allen to have a better life to start the magazine that he had been dreaming of. This wasn’t going to happen. And it’s then that I think he understands really for the first time that he is on his own, that he is going to have to make his living and support Virginia and his mother in law and himself with his mind, with his imagination as a writer.

Speaker How’s that great and can you add on a bit more about the fact that, however, it was virtually impossible to make people didn’t make their livings as a right? Yeah. In America, then if you could just go on to the and a little. Yeah, of course.

Speaker Well, for most writers, it’s always been difficult to make a living in America, for Poe, that was especially true. He was never able quite to do it. He suffered tremendously. He worked in drudgery as an editor as as a as a writer of book reviews and columns, work that was beneath his talents, beneath his ambitions, taking on work solely for the sake of supporting himself. That never that never quite eased up throughout most of his life. There was this this punishing sense of diminishing returns. You see him complain about it in letters that he doesn’t have time for the creative work that he wants to do for his tales and for his poems because he’s turning out this copy. I mean, you see him working 12, 14 hours a day as as an editor or as a hack writer. And I think it almost ruined him as as an imaginative writer. That’s been the case for for many writers. You see it with Hemingway, but for Poe, it almost it almost destroyed him. I think the having to make a living as a writer. Writers of imaginative literature know that if you have to work as a hack turning out copy that’s beneath you, it saps all of your life force for the work that really matters to you. And so it’s somewhat extraordinary, I think, that we have as much creative work as we do. When you look at the years he spent writing garbage that that he knew was was garbage, he he needed to do it.

Speaker What does it say about him that he had that energy and that depth and their ability to keep going?

Speaker Well, look, it was the only thing he knew how to do. I mean, he didn’t have any other skills. I think he had tremendous resolve. I think he cared about his mother in law, Marty, Clem and Virginia, in a way that was tremendously feeling and profound and genuine.

Speaker And he had this responsibility to them.

Speaker You see him suffering not only so he himself can survive, but so his mother in law and his wife could perhaps not suffer as much. And I think it’s I think it’s so noble of him. You could say, well, that was his job. He was a husband. He took these two women into his care. Well, that was that was he was supposed to do know.

Speaker Many don’t. Many don’t.

Speaker I think he did it with such a tenacity that you can’t just credit his ambition, his ambition as a writer, his ambition as a literary artist. He was trying to make money. And it was never it was never enough. It was never enough money to make. He never he never did make enough for them to live comfortably. I think that his tenacity as a husband and as a as a as a caring man, it’s not enough commented on. You hear about Po the scoundrel, you hear about Po the drinker. You hear about Po the self mythologize, or you don’t hear enough about Po, the family man. And I think I think that’s something of a travesty and. And it makes sense, I think, when you look at the paucity of affection he himself had growing up, certainly the paucity of affection he suffered at the hands of his foster father, his biological father disappeared, his mother dead at 24. It makes sense to me that he would feel this obligation to Virginia and to muddy clam. I’m not surprised by that. That was that. That’s good. Thank you. Just in to CNN, I’m going to stop it.

Speaker Just stop me and say can you know, OK, but I keep going to I want to go back to that moment when he realizes he got nothing from John Lennon, because part of the problem we’re having with the film is setting up those sort of moments of tension and suspense. You know, you want to you want the viewer to say, oh, my God, what’s going to happen? Yeah, OK. So could you just say something along the lines of what’s he going to do? Yeah. Yeah, but but nobody in America made a living right in those days. It was almost impossible. You don’t have to go into why so long. Fellow was probably one of the exceptions, right? Well, but this was even I guess he was beginning. He was beginning. Yeah. In thirty four. Yeah. I mean there were a couple but yeah. But if you could just kind of without going into it. OK, sure.

Speaker But, but hardly anyone made a living as a writer in those days. But what I’m trying to do is set up a little moment of like suspense, you know, oh my God, how is he going to do it?

Speaker So, OK, so this is right prior to the Southern Literary Massacre, right? Oh, OK. Yeah, if you could just say something. So tell me when to start. You want to start with the will. No, no, we already did.

Speaker OK, so you’ve already said he’s realized you have to make a living as a writer if you could just add on. But nobody made a living as a writer of those days. So it’s really, you know who and I can’t imagine how Poe thought he was going to do it.

Speaker OK, OK, you got to kind of raise the question, gosh, how can he possibly do you want me to frame the decade in the 18 30s? You want me to say no? I think we’re just going to add it on. OK, just just added on kind of an addendum.

Speaker No, nobody in America made a living from writing in those days.

Speaker What’s he going to do? I can’t imagine how he thought he was going to succeed at that.

Speaker That was great. That’s it. I’m sure that’s fine, because I think that will get them to the Southern, OK, but yeah, I would just, you know, we need a few moments. Part of the problem of not having a voiceover narrator is it’s very hard to set up in this moment.

Speaker But I think it’s a good choice. I think it’s a good choice.

Speaker We’re really determined not to fall back on that. So the thing about wanting his own magazine, I mean, you’ve already referred to it, but I think it sort of became a real idea when he was at the Southern Literary Center and he you know, he started to chafe under working for anyone else. Could you just talk about I mean, put it in the context of 18, 35. He’s in Richmond. He’s working like hell for the Southern Literary Messenger. It’s doing well largely because of him. Yeah. Can you talk about how this ambition starts to take root and don’t take us forward in time. Just leave it there in 1835. Nineteen thirty five that you know, so he’s thinking, well, why not be my own boss.

Speaker Why not. Yeah. And stop, stop working for others. Yeah. So we’re making thirty five POWs working for the Southern Literary Messenger and it’s then I think that the idea for his own magazine really begins to take root. He must have felt as if he didn’t want to be the work force of these proprietors, that he wanted to be able to implement his own vision and publish the work that he wanted to publish and the way that he wanted to do it.

Speaker You don’t want to get that style.

Speaker OK, so, so, well, maybe you could just add on something about, you know, as it was he was going to hold onto that for years. It was going to in some ways consume him, or at least he would never would let it go.

Speaker It’s kind of see, I have. All right. I have a theory that actually begins in West at West Point when he begins publishing his own, when he means printing his own poems. And he was actually selling these to his to his fellow. But I don’t want I know I don’t want I don’t want to go back to West Point if we’re here in eighteen thirty five, because I was going to I don’t want to confuse things. So, so OK.

Speaker Thirty five southern southern southern messenger.

Speaker I think it’s good to go back to West Point because that, that’s like the point of West Point, the two points of West Point and he’s doing it for his father. But also it’s the start that he’s getting this. He’s getting attention for writing.

Speaker Yeah, let’s do that. That’s fine. I mean, all we need to do, we just want to plant the seed. Keep coming up. So maybe you could say, you know, in that time at West Point, he printed homes. He sold them to his friends. And I think that’s where he OK, whatever.

Speaker But also just the the other thing that it I mean, slightly off topic, but picking up on your sort of the complexity of like he’s writing, from what I understand, he’s writing really funny things to get a good sense of humor, you know, especially in the officers something. And it’s a good seed to plant as well as we don’t when we don’t have any examples, you know.

Speaker So it doesn’t. Yeah, we don’t. Yeah, I don’t think so. Well, you want to hear an example and we don’t have one. Yeah.

Speaker So what was the question then would be what is the connection between Previte. Sorry. What is the connection between. Printing his poems and being able to sell them to the other cadets at West Point and his aspirations to have his own magazine. Well, you know, when Paul was printing his own poems and selling them to his fellow cadets at West Point, he was in control of that. Right. He didn’t have to answer to anybody. So I think in eighteen thirty five, when he’s working at the Southern Literary Messenger, it’s then really that the idea for his own magazine really begins to take root because he recognizes that this drudgery of working for other people, it doesn’t suit his personality, it doesn’t suit his attitude was not good at taking orders.

Speaker And that idea to have his own magazine, it never went away.

Speaker You know, that that was the that was the real beginning of it. The real genesis of I’m going I’m going to do this and I’m going to be a success at it.

Speaker That was good. OK, yeah, that’s great, because actually what I want to do then is ask you what we might as well do it so if we could jump ahead in time to when he’s in Philadelphia having, you know, first. So he left Richmond. He went to New York and went to New York very briefly because it was the middle of the financial panic and it was a disaster. And then he went to Philadelphia and things started to get better. And that’s when he worked for Berton’s magazine and he worked for Graham’s magazine. And then he published the detective stories and he published some of his best known tales. Not the Broadway Journal. Right. Was that after? Before that them before the Broadway Journal, if you could talk about. So he’s in in Philadelphia. Lee, do you remember exactly the dates? It’s about eighteen thirty nine 1840 for the OK and it’s sort of about eighteen, forty, forty one starts know he’s making a living selling the tales he’s.

Speaker But he’s still in Philly not New York.

Speaker In Philly he didn’t move to New York to eighteen forty four. But you could talk about the early 1846, you know, put it in the context of his. He’s doing OK, you know he’s he’s making a living. He’s still a tremendous hackwork. I mean, he’s working day and night. I mean, during the days working for these magazines at night, he’s trying to write the tales and poems and trying to keep the creative work going. If you could just sort of describe that, you know, he’s he’s getting a name for himself. I mean, murders. And the rumor was did quite well. The other tales and tales of the grotesque and arabesque. And, you know, he was selling. People knew his name. People were beginning to. And where was his ambition for his magazine then? I’m just sort of trying to revive the idea that he was still he still had this dream and he thought that maybe he was getting a little closer, maybe not. I don’t know. Whatever you think this is.

Speaker Eighteen thirty nine. Yeah, thirty nine. Forty forty one. OK, so it’s about his death was forty eight. Forty nine. Forty nine. So it’s almost a decade. Yeah. Before he really began earning the raising the money for, for his magazine right before it ever became before.

Speaker But he still had this, he was calling the pen then which was sort of a play on Pennsylvania, but also, you know, became a stylist. But then he he had a he had a prospectus for.

Speaker OK, so let’s going to call the pen. OK, so let’s see. Let’s see. We’re talking about the early eighteen forties. Poe is in Philadelphia. It’s then when his reputation really begins to ascend, he’s working for magazines. He’s doing lots of hack work during the day. He’s writing his tales in the evening. He’s beginning to have some success. And the idea for his own magazine is still percolating at this time.

Speaker Um, his idea for the magazine getting success, writing his tales and I have worked throughout the day.

Speaker Do you want to mention Berton’s or Gramps? Is that necessary or do you want to keep. I’m sure if you want to. I feel like too many names. I always throw people off.

Speaker You should just say magazines. He works for a couple of different things. Editor for a couple of different magazines has trouble with the editors. Of course we could work that in, which is another reason why he’s so.

Speaker So in the early eighteen forties, Poe is in Philadelphia. He’s beginning to have success. His reputation is ascending. He’s working for a couple of different magazines, having trouble with the editors, as always, writing hackwork throughout the day at night. He’s working madly on his on his tails and on his poems. He’s doing all right. But this this must have been a confirmation for him that he really needs to have his own magazine, that working for others and having the kind of trouble that he was having with these editors and with the lenders and the proprietors was more than he wanted to deal with.

Speaker Yeah, that was good. That’s good for sure. Yeah, I think that’s fine. OK, I mean, we can go back later and say there’s but but we can keep moving along. The other thing that happened though in those years is that’s when in Philadelphia, that’s when in the midst of this seeming, you know, bright moment or at least hopeful moment, that’s when Virginia has their first haemorrhage while she’s playing piano and singing one night and then was forty one or two lead, you remember, I think it was about eighteen, forty two and three and.

Speaker He he he recognizes.

Speaker OK, so.

Speaker Yeah, I probably want to say 41 or 42 or forty three. I just want to say that while he’s in Philadelphia, it’s in 18, whichever 40, that that Virginia has her first hemorrhage, while I only say eighteen, forty three leaves usually right on these things.

Speaker OK, well, you’re looking it up, OK, we haven’t done it. So I’m in Philadelphia. Things seem like they’re more hopeful than they knew then. He’s he’s building a reputation. He’s making a living. And then.

Speaker OK, so it’s in Philadelphia in the early eighteen forties when things seem to be going OK. He’s earning a living. He’s making a reputation for himself. There’s almost this sense that things are going to be all right. And then in 1840 to Virginia has her first average while playing the piano, and that must have been anthropos. He must have known at that moment that this was not going to end well.

Speaker Thanks. How was that that was good. I mean, how do you want to say more? Yeah, tell me what you know, what did. So his mother died of tuberculosis. His brother probably did. No one really knows, but certainly many people did around him. What do you think was, you know, what was going to how is that going to affect him? How is a.

Speaker His mother died of tuberculosis. His brother, Henry, probably died of tuberculosis, Virginia now has tuberculosis. What is going on in Poe’s mind at this time?

Speaker The tremendous defeat he must be feeling.

Speaker This sense of cyclical destruction is never going to be able to get away from this disease and the cataclysm that ensues from it.

Speaker You know, there’s a sense in which he could never get a break. All his luck was bad.

Speaker I think there were men such as his foster father who believe that you make your own luck in the world.

Speaker I’m not sure that’s ever true. Tried as hard as he could, I think, to make himself lucky and he could never do it. What he found out that Virginia was sick. It must have been a confirmation for him that he was doomed. It really does seem extraordinary. I mean.

Speaker To lose, to lose that many, to lose that many people, I mean, Poppo lost everyone who had ever meant anything to him.

Speaker Then we wonder where this darkness comes from. We wonder. About his fatalistic vision and his escape into dreams and his preference for the night. How do we wonder?

Speaker It’s usually folly, I think, to connect a writer’s life to closely to his work. Begs us to do that, I think I think that connection, that nexus is inescapable with Pop and let’s be honest, the life of the writer always affects the work with Poe. I think that’s true probably more than most.

Speaker And I’m not sure there’s any grand mysteries about. His vision of the night and his. His tragic view of living. When you have that much bad luck, when you are subject to that many heart.

Speaker I say heartaches, it’s not just a heartache, I mean, it was more like a heart wrecks, you know.

Speaker It’s no, it’s no surprise to me.

Speaker I was going to go into the French there a second, I was thinking about the whole thing about weather, but the was great. Well, no, let’s let’s do the French.

Speaker I don’t know what. I don’t know what. I don’t know why I thought of them. It has to do, I think with his vision of the night and what I wanted, what I wanted to say, you can start and you could stop me. But just while I have it, here is Baudelaire, a Valerie. These were visionary poets and I think they recognized in Poe a fellow visionary in a way that his American compatriots could not. They saw in him somebody who was willing to embrace the darkness. They saw in him, a poet who separate himself from the quotidian and the banal and the humdrum, someone who was advancing.

Speaker A new way of seeing the question, of course, becomes why? Why the French and not the Americans?

Speaker This, I think, is complicated. It has to do with national temper, with the national tenor of thinking of apprehending. Poe was disgusted by his fellow Americans. He had nothing good to say about them ever. It was partly because he felt betrayed by the American dream. He felt betrayed by American promise. As hard as he worked, as much as he strived, he could never make it that that seemed to him a tremendous transgression against his own trying his own abilities, his own talent. And you seen his letters and you see in his essays. The idea that Americans are frivolous or shallow, they care about money, they don’t have it in them to appreciate his vision, the disappointment of that, the dejection he felt. Was was paramount.

Speaker That was a sort of roundabout way to America, I think, from France, but we could really use the context of the whole resurrection by the French. So maybe we could start off by saying something like, I wasn’t he was it like 20 years after his death or so that terror started and abolished.

Speaker So I was the first trans translator of of Geko. I don’t have the dates as Lee here.

Speaker Lee, could you check? She left. But let’s just see and let’s see if I could do it this way.

Speaker So about 20 years after Poe’s death, he’s still being read. He’s not being taken all of that seriously. He’s considered the dark boogeyman. Griswold’s version of him, Griswold’s pollution of his image has stuck. And then we see the poets in France, Baudelaire, Malama, Valerie, taking an interest in Poe’s work. They recognize in him a fellow visionary, someone unafraid of the darkness, someone who wants to cut ties from the quotidian and the banal and the humdrum, someone who wants to advance a new way of seeing. And they’re enthralled by this. And Baudelaire begins to translate into into French. And he’s something of a sensation there in a way that he never was in his homeland.

Speaker And it’s very curious that it took this boomerang effect, that Poe’s importance here in America had to go through France before it arrived here and bowdlerised to his to thank for this.

Speaker You know, I didn’t say Charles Baudelaire, the poet I know. I was going to say it was a perfect answer, except for that.

Speaker But that’s OK. We can go pick that up. So maybe if you could just say it, I don’t know, just started off by saying that a sort of surprising thing or an unexpected thing began to happen. French poets and.

Speaker Yeah, and they and then an unexpected thing began to happen. The French poets began to take a very keen interest in Poe’s work. The important French poet, Charles Baudelaire translated Poe’s tales and poetry was absolutely enthralled by Poe’s work saw in him a fellow visionary, someone who was unafraid of the darkness, unafraid of cutting ties with the quotidian and the banal, someone who was advancing a new way of seeing as Baudelaire himself was trying to do.

Speaker And so it’s extremely curious that Poe’s reputation here now among us had to take this boomerang, right? We had to go from the shores of America to France and then back again before we could fully appreciate this writer without whom we don’t have a full understanding of American literature.

Speaker How was that? Did I get out of bed and I thought, OK, yeah, all right. I think that I think we got that. Yeah, that’s very nice. Thank you.

Speaker And we don’t really have that yet in a good way. But he’s also, like you keep referring to, he’s so imbued with desperation, melancholy, part of circumstances like that, he can’t control them. Yeah, that’s right. So he’s sort of back and forth.

Speaker That’s right. So are we rolling? OK, so I want to I want to let me see how this sounds sort of informal, but. As real as Poes melancholy was, he was this tremendously complex individual. He wasn’t just this grim reaper. This this man of the night, he could be tremendously funny. He was witty. He was a kind of ladies man. He knew what he was doing. I think with the Poe, the vampire image, he was a smart self mythologize or he knew that the public wants their writers tormented, tortured. And so he would drink because the drunk poet is the more attractive poet. He was a literary bad boy before anybody really knew what that meant.

Speaker And I forget what you were saying, John, about about the complexity.

Speaker Yeah, just I just think I mean it it’s hard to get in one sentence. You know, you can say yes in two four. I mean, I think he he was well, early when you’re talking about how people don’t know he was said you were.

Speaker Yeah. OK, good. So let’s talk about that. So the contradictions in his character, he’s going to work. He’s battling with these editors and proprietors. Meanwhile, he’s this tremendously loving family man. He doesn’t hesitate to cut ties, and yet he’s also profoundly loyal. He’s this prophet of the night. And yet he could also be tremendously funny. He was tremendously witty. He was this isolated, and yet he was something of a ladies man. The contradictions in Poe, the paradoxes of Poe. This is something that is too little remarked on. I think we have this this image of Poe as the vampire. And this is what D.H. Lawrence accused Poe of being. He said that Poe didn’t so much write about vampires as he was himself a vampire. And that said, with typical flourish by Lawrence. But Poe knew what he was doing with that. I think he understood what the marketplace wanted. And it’s not to say that that melancholy wasn’t real and that it wasn’t devastating, but that he was able to perform. He was a brilliant performer on these lecture tours, that he would go on three, four or 500 people packing a lecture hall. He, remember, was born to an actress. He was born into the theater. And he had these genes. I think he was he was a true vaudevillian. You know, there’s it’s hard to reconcile, you know, I think, John, what you’re saying, it’s difficult to reconcile because on the one hand, the depression was severe and it almost killed him. On the other hand, he can perform and be comedic.

Speaker How do we how do we reconcile this?

Speaker I don’t look at her. OK, well, can you talk on a little more about another tension related is that he loved writing the popular stuff. He loved, you know, selling well. He loved, in a way, writing just garbage, that people loved the fluff that people liked. But he also wanted to be taken seriously as a great writer, as a deep writer, as an important writer.

Speaker So we have imposed two kinds of writers, we have the producer of popular tripe that he knows is going to sell and he needs to do that in order to survive.

Speaker And yet we have this other writer who has very long standing literary aspirations. He wants to be taken seriously.

Speaker Many writers try to hold those in equilibrium, was pretty successful at it.

Speaker When you look at the quality of work he was producing, certainly throughout the 30s and 40s.

Speaker They tend to fall in to one or the other camp. He was a pretty successful writer of garbage. He really was. I mean, his bad stuff is really good.

Speaker But his literary stuff was also, I think, of of the highest quality, it had all of the molecules to endure and it has.

Speaker Yeah, you want to talk a little about the criticism, and I’m thinking mostly the Southern Literary Messenger and soon after when he starts to really turn on his skills as a as a critic. Yeah. He also becomes the Tomahawk man. But he’s he’s doing it to a higher calling. He’s trying to elevate American literature. Right. And he’s kind of on this mission to to make it every bit as good or better than the European literature and literary criticism.

Speaker Yes. I suppose criticism, I think, holds one of the keys to his to his seriousness and to his ambitions, not just for his own work, but for all of American literature. He wants to hold it to a very high standard. He is throat as a critic, severe, brutal.

Speaker They call him the Tomahawk man. You don’t want to get a bad review by Poe. Longfellow found that out.

Speaker But post criticism has been taken seriously by some, not so much by others. But it is there where I think we can begin to unravel what Poe really thought about the aesthetics of literature, the mission of poetry in particular, and what he thought art should be doing. He had important theories about the utility of of art. He wasn’t just somebody who was creating on the sidelines. He was intimately involved in the critical mind of the literati and of what he thought American literature should be, where he thought it should go. He was abjectly disappointed in American literature. It was fluff. It was not to be taken seriously. You can say that his hatchet jobs were in order to garner attention and fame, and they certainly did that for him. But let’s not discount the the real vision and and the principle that that guided those not saying that that that he didn’t do it for fame and for attention. But that is, I think, to discount the the important principle that underlay that criticism. He had he had genuine visions for the trajectory of American literature, and he wasn’t shy about saying what those should be and wasn’t shy in cutting down those who transgressed against his standards of art.

Speaker I most wanted to begin talking about the raven there, because there’s a real disconnect, I think, between his criticism and what he what he actually did.

Speaker Yeah, well, we could get to that. But but before we do that, can we go back to like when he published Tamburlaine, which was kind he was saying earlier notaris very early, would you feel comfortable, you know, enough about it to talk about sort of what promise that held, but, you know, keep it in that time. So, you know, it’s a very naive voice. He’s totally ripping off Byron. Yeah, that’s that’s the problem. There’s a there’s something there.

Speaker We have a date for Tamlin.

Speaker Is he is this post West Point? No, it’s free. Was OK. He was lead, ran away from home, ran away from Richmond, went to Boston self published this little, you know, eight poems or something in the title page.

Speaker Title page says by Bostonian he didn’t even want to take credit for it, but that’s probably because he had creditors chasing him. Yes, indeed. So so we could say, um, I’m sorry, what date do we have a timeline.

Speaker Eighteen, twenty seven.

Speaker OK, and it’s post first publication. Is that right. Yeah. OK, yeah. He’s just eighteen years old. Eighteen, twenty eight. Twenty seven. I’m sorry. So in eighteen, twenty seven PO publishes his first book of poems Tamburlaine.

Speaker They’re heavily indebted to Byron, that kind of Byronic pomp and posing and adventurousness.

Speaker But they also hold tremendous promise. There’s something there that is not yet developed, but that over the next decade certainly PO is going to shine into perfect little gems. Yeah, it’s true, my, my, my, my opinion of Tamburlaine is not is not very high, but but you’re right, I think, Eric, that it’s that there’s something there’s something there. There’s the promise there, I think is is is undeniable. And also, I think it’s important to note that that imitating of Byron Poe wasn’t alone in imitating Byron. There’s a sense in which in the mid 19th century, no other poet in the English language was as influential as Byron. So Poe certainly wasn’t alone in that imitation, but it was necessary. He’s 18 years old. When Tamburlaine comes out, that is the time when when poets are under the spell of their of their heroes, you know, and it didn’t get any more heroic than Byron. So although this was was a bald imitation, a bald Byronic posing, it also had important elements of Poe’s own individuality and his own poetic vision that were in the next few decades to to become manifest.

Speaker And if you could just add on a little more after a drink about the fact that you can actually see this, that he’s beginning to shape this idea of art for art’s sake, that the poem, the poem stands on its own. Yeah, and right.

Speaker It’s also around this time of Tamburlaine that Poe is beginning to forge his concept of art for art’s sake, that art didn’t have any business with teaching or with instructing, with morality or with spirituality, that the poem was self-contained, that we need no recourse to anything outside the poem.

Speaker It is at this time that these ideas are beginning to take shape in him.

Speaker We already talked about the heresy of that tactic.

Speaker I don’t know if that that’s later that. Yeah, that’s there. Is that OK? OK, so seed for the great right thing.

Speaker Griswold, do you want to talk about Griswold, how complicated you want to get, because I think I think these guys had a handshake behind doors, you know?

Speaker Oh, God, yeah. You’re one of those.

Speaker Well, I mean, you know, you can almost I didn’t want to get into this with Longfellow either.

Speaker But, you know, we have letters and even in his own reviews, we have people praising Longfellow. And and you know that when he was at the the the Broadway Journal that that he and he wrote his own right. This this he had the Greek name of this guy. Nobody I forget his name, but it was the Greek name for nobody. And this was the guy who was writing in to to defend Longfellow. And then Poe would respond. Of course, that was Poe if I was doing this, you know. And so, I mean, this goes back to what Jim was saying earlier about the contradiction of this guy. I mean, on the one hand, what is what he’s doing with Longfellow is absolutely heartfelt, absolutely genuine. On the other hand, this is all a ploy. You know, there’s something of that with Griswold to, you know, Griswold had. Had lots of praise for Pope, I think he was a scoundrel, but I think that Pope understood that Griswold was good for his career in the same way that people understood that this image of himself as the raven, this image of himself as the reaper, was good for his sails. He understood also that this scoundrel, Griswold, was good for him as well, because Griswold was going to disseminate all the dirt.

Speaker I mean, that’s just what I mean about collusion that there was.

Speaker Well, let’s back up. OK, you know, of course, in the film that Griswold comes up two or three times at different times. You have an actor doing this. Well, now we don’t we couldn’t afford it. I wish we did. But the cast. So they first meet in Philadelphia in the early eighteen forties, the same period that the tales have come out, that the detective stories have come out and oppose making a name for himself. And and Griswold has a name for himself too. And so they made this kind of equals. And if you could just talk about it, that moment that Griswold is this is this anthologist. He’s putting together a book on the poets and poetry of America. And Poe, of course, wants to be in the book.

Speaker And he says it was Longfellow’s collection that he wasn’t in. All right. Right. OK, so we’re talking about Philadelphia in the early eighteen. Yeah, early eighteen forties because he moves to New York in nineteen forty four.

Speaker OK, so Philadelphia in the early 40s, Poe meets Chris Wall. They are both on the ascent. As writers, as editors, Griswold is an anthologist, he’s putting together a collection of American poetry in which Paul was included.

Speaker What happens after that, Eric? Well, one funny thing is DPO desperately wants to be included in this anthology and is although at the very end and then post reviews the anthology and kind of trash, you know, he’s kind of it’s it’s a mix. Yeah. So what does that say?

Speaker Poe really wants to be included in Griswold’s anthology, and he is he’s included at the end. And then when the anthology comes out, Poe reviews it and it’s a mixed review at best.

Speaker As you can imagine, Griswold was not pleased by this.

Speaker Perhaps that is the beginning of the enmity between these two men who made lots of enemies with his reviews.

Speaker Griswold was, I think, the the lifelong enemy.

Speaker I mean, that’s where it gets complicated to even what we call that now a frenemy. You know, that, as I think I said that earlier, though, that he recognized Griswold was was say it again, OK, say it again.

Speaker But at the same time or something.

Speaker So Pope earns this enemy in Griswold by penning this decidedly mixed review, but it’s more complicated than that at the same time. He and Griswold are in a kind of collusion. They understand that a feud, a literary feud, sells well and each use the other to forward his own notoriety, his own reputation.

Speaker They were they were dastardly in that way. Yeah, it’s incredible, really.

Speaker Tell me what else. That’s great. Is that OK? Can we jump ahead? Yeah.

Speaker Do you know anything about in so New York City after the raven pose, a basically superstar is like an overnight celebrity in the literary world. He’s invited to these these literary evenings at the home of forgot her name. But you could just say literary evenings and fashionable New York society. Griswold is invited as well, as well as in New York now, too. And he’s also a literary celebrity. But the two of them still have this sort of tangled thing, Griswold and Volvo. And it’s made more complicated by the fact that he starts to have this kind of public flirtation with a woman, poet, Francis Sargent Osgoode, for whom for whom Griswold obviously has his affections as well. So I don’t know if you could I don’t know if you want to sort of take a stab at that. Well, let’s see where I can go with that. We’re talking about New York in 1845 post just post Raven.

Speaker OK, now let’s see New York in 1845. This is post. Raven Poe is something of a celebrity, although a broke celebrity begins to be invited to literary parties is something of a literary socialite meets the poet.

Speaker Fanny Osgoode begins to have this very public flirtation with her. This does not please Griswold because Griswold has affections for Osgoode. So you can imagine what he felt about that. Yeah, you’re right, and that at that that complicates the whole the whole thing and inject it injects a certain element of bile into their interrelationship. It it elevates the bile to a next to the next level that never considered.

Speaker That’s good.

Speaker Maybe. Would you mind taking another stab at it and maybe started, as you know, pun Griswold crossed paths again. Yeah. 45 in New York in 1845.

Speaker This is post. Raven Poe is very well known. He still broke, but he’s something of a literary celebrity. He begins to become part of literary society in New York, parties, dinners and such.

Speaker He meets a female poet, Fanny Osgoode, and begins to have a pretty public flirtation with her. And it’s at this time that he and Chris will cross paths again and not in a pleasant way because Griswold has, well, affections for for Osgoode. So you can imagine the degree to which that increase the bile between these two men.

Speaker Yeah, right. I mean, it’s a literary feud. I don’t know if you want to say, yeah, literary feud is also becoming their literary feud in particular. Yeah, I mean, I just felt like saying a little more about how OK, so increase the vibe between these two men.

Speaker And let me start from the beginning. I want to tackle just if you want to say a little more about what had been a literary or personal kind of gotcha kind of literary envy and jealousy is getting this other dimension. Got you. OK.

Speaker So what in the early 40s had been primarily a literary feud between Griswold and Poe all of a sudden turns personal in New York in 1845 when Poe meets Osgoode.

Speaker Personal terms, personal is that is that that turns personal, another just so you know, we’ll double check everything.

Speaker We’re not going to make you know, we won’t have you saying anything that isn’t totally supported by Abkhasia because, I mean, I don’t know. I mean, that seems pretty.

Speaker But the other thing that you talk about complexity, he’s doing this flirtation.

Speaker All the while, his life was like dying. It’s another layer, if you want to comment on that.

Speaker I mean, you know, this is another another example of the complexity of PO and the fact he’s, you know, as much as you can admire him or feel sorry for him, he also in some ways had a knack for turning people against you. OK, so.

Speaker It’s another one of the contradictions we see in post personality, this public flirtation with Osgoode, his wife, Virginia, is at home dying of tuberculosis and he is at home, this dedicated family man out and about. He’s carrying on with this other woman. In this way. It was almost as if Poe couldn’t help but to be a contradiction to himself, couldn’t help but to be a paradox, couldn’t help but to have this roiling and Timimi within him. This imp of the perverse this knack for turning people against him, against his own best interests and.

Speaker Could you talk a little bit about, you know, why do you think one day one person we interviewed put it was when when somebody grows up struggling for love, pleading for love, feeling unloved, it makes them almost feel like they’re going to make themselves unlovable.

Speaker W.H. Auden said that post seemed to have won from women partners with whom he could play house and laps into which he could weep. Well, yes, when you have post history, yes.

Speaker He must have had a pretty sincere notion that he was unlovable, that he didn’t deserve love and perhaps some of his self-destructive tendencies come. From this from his inability to see himself as lovable as Harveyville, as worthy of affection, as worthy of devotion, I think when you’ve gone that long without it and when it forms the basis of your existence, unwanted, unloved feeling, not important enough not having your life validated, that could do one of two things to you.

Speaker I think it can turn you into somebody who. Does everything right, because you don’t want to make any mistakes in in your affairs of love and devotion and compassion or turns you into somebody who’s a bit too careless and reckless. Because there’s this nagging notion, this pervasive nagging notion that you will never be good enough, that you don’t deserve it, and perhaps this is what we see with Osgoode, it was it was self-destructive for me.

Speaker Virginia was was not going. Virginia was in no position to be offended by this or to leave him. But I’ve got to say, it is a bit of a blemish on on post character, even if he didn’t mean it, even if he was doing it for show.

Speaker Um, there’s something very distasteful about it.

Speaker There’s there’s also there’s also the the possibility that he did it deliberately because he knew that Griswold had affections for her and so he was a master at that.

Speaker He was a master at taking animosity and ratcheting up to the next level.

Speaker And they both knew it would help, so. Yeah, exactly, could you just to that. Yeah.

Speaker And it’s not to say that the slight that Griswold felt at Poe’s public flirtation with Oswald wasn’t wasn’t genuine, but they both recognized, I think, that another public feud was exactly what they both wanted and needed.

Speaker And could you also add on that for Fanny Osgoode and they also that that was a marketing ploy in a way.

Speaker I mean, this public flirtation, it was maybe emotionally heartfelt, but it was also a way to sell. Yeah. As she was a terrible poet. I mean, people had a poster. I don’t know if I want to I don’t know if I want to say I say that in my introduction to the Annotated Poe that that Poe had this penchant for under praising talented male writers but overpraising talentless female writers.

Speaker Osgoode understood, I think, as well as Griswold and Poe himself, that this public flirtation was good for her career.

Speaker And the. Well, I guess that’s only, by the way. Yes.

Speaker Oh, so shall we do that? Yeah, I think we’d better tell people what’s going on. OK, shall we keep going.

Speaker I continue. Change the tape. All right. OK, so we need just a sentence or two about this moment in eighteen thirty three.

Speaker And Poe’s living with his new little family in this tiny house in Baltimore. Totally poor, desperately poor. And then he has a break. He wins a literary contest manuscript in the bottom.

Speaker Eighteen thirty four. Thirty three. OK.

Speaker So it’s 1833, Poe is back in Baltimore.

Speaker It’s his first family environment, he’s there with Virginia. He’s there with his mother in law there.

Speaker Sorry to interrupt. She’s actually there aren’t married yet. Oh, they are married. Just his aunt. And his cousin is only like this. Got you. Yes. Oh, right. Right. Sorry, but that’s. But other 33, right? Yep.

Speaker Thirty three. After West Point, West Point.

Speaker No, no, I think you just you know, I take your coat. Well, it’s a big. So.

Speaker So it’s 18, 33, Poe is back in Baltimore.

Speaker He’s with his cousin Virginia and his aunt and his brother Henry, they’re living together in this shack.

Speaker They’re poor as poor could be. He’s trying to make a go of it. Things seem.

Speaker Desperate, and then there’s this break, he wins a a literary contest for his story called Manuscript in a Bottle.

Speaker I wonder how much money you got for it? I think it was 500. No, not 500. It was something like 50 dollars.

Speaker Yeah, in the US I think it was 50 dollars. That’s a lot of money. And even more important, one of the judges, John Pendleton Kennedy, took a liking to him and decided to help him get a job at.

Speaker One of the judges of that literary contest, John Pendleton, Kennedy, John Pendleton, Kennedy, Pendleton, Kennedy, yeah, one of the judges of that literary contest, a guy named John Pendleton. Kennedy took a liking to Poe after after the contest.

Speaker And it was Kennedy who actually helped to get a job, a job that he was in dire need of.

Speaker It’s great. Is that OK? Thank you. And after that is what job? That Southern literature. It’s now OK, because I thought it was white. Who was? Hugh White was the editor of The New Way. There was sort of a someone described him as a kingmaker of literary ideas around Baltimore. And he was he was rich in his own right, but also very literary. And so that that was fantastic. Thank you.

Speaker What I wanted I had this vision of. About the reason I had this vision of.

Speaker There was going to be someone, either a voice over or someone else saying, you know, what is it about the raven?

Speaker And I was going to say, well, it’s catchy. Emerson called Poe the jingle man ouch. That’s that’s rough.

Speaker The greatest English language poet of the 20th century beats so that the raven was insincere and vulgar.

Speaker He also said it was metrically and rhythmically deaf, that it, like all of Poe’s poetry, lacked moral gravitas, that it was all smoke and mirrors and that it had nothing to say. This idea was reiterated in a famous denunciation of Poe, written by the poet critic for Winters, in which he accuses Poe of being an obscurantist and not an accidental obscurantist.

Speaker Are we OK without sound? Let’s keep going. Do you want to go out and say, I know, I just I’m afraid I’m going to start. I thought they were going to come in. Yeah. I think we’re OK, so now it’s empty. I don’t know what that was. All right.

Speaker I think it going in the auditorium.

Speaker Anyway, but a nail biter in here. So back to the grave.

Speaker OK, well, what is it about The Raven? It’s catchy. Emerson called Poe the jingle man. Ouch. That hurts. The greatest part of the greatest.

Speaker The greatest English language poet of the 20th century, Obetz said that the raven was insincere and vulgar.

Speaker They also said it was metrically and rhythmically deaf, wasn’t alone in that the the important poet critic for Winters’ wrote the popular denunciation of Poe in which he accuses Poe of obscurantism and not accidental obscurantism, deliberate obscurantism, obscurity for the sake of obscurity.

Speaker And in addition, Winters’ says that like like Yates, Winter says that Poe’s poetry lacks moral weight, that there’s nothing really being said here. It’s all sound, it’s all technique.

Speaker The Raven is the perfect poem for people who don’t like poetry. How do we account for the tremendous success of this, it’s probably the best known poem in the English language. Certainly the best known American poet.

Speaker It was also a poem for which.

Speaker Polidor later felt some regret the notoriety that he gained as a result of that poem was something of an albatross for him. Children would accost him on the street with taunts of nevermore. You know, I think he was afraid of being typecast or pigeonholed in that way. And it was a well-founded fear, I think. I mean, he has been it’s almost impossible to think of Poe without thinking of that raven on his shoulder.

Speaker I wonder if you’ll have anybody else talking about the Raven, I mean, that’s going to be a big part, right? Yeah, yeah, we do have people talking about it.

Speaker I mean, I’m curious, what what do you think of the raven that have your drink, Fensterman.

Speaker The Raven is a meditation on remembering on the inability to forget.

Speaker Like all of Poe’s work it. Like most oppose work, it contains this debt love.

Speaker Coming back, Visitacion, a haunting and the narrator’s the protagonist’s inability to let to let go.

Speaker Um, the thing about the Raven, which is the thing about carbonation, it’s hard.

Speaker Forgetting, remembering, meditation on forgetting, remembering, and I do I do think it’s a bit odd that that the raven is so popular because it’s it’s a bit hard to pass. It’s a little bit difficult to understand. And it’s especially odd to me that that this is still given to schoolchildren because it is so obscure. And it it takes a lot of work to untangle Poe’s meter, to untangle the syntax and to try and get at the hub of what he is saying. But this charge by Emerson of the Jingle Man, there’s something to that. And I think that that’s where the popularity comes from, is that the poem gets lodged into your ear and stays there and children quite like that. They quite like being able to recite the sounds of it, even if they don’t fully understand what it means. And I should say that that that’s the beginning of understanding. What it means is getting the sound. If you can get the sound and if you could possess the sound by memory, then you could begin to make sense of what the sound is saying. And The Raven is a widely memorized poem, right? If people have a poem memorized, it’s or let’s say if Americans have a poem memorized, it’s the Raven.

Speaker Could you talk a little about the fact that on one level, it is kind of frothy? I mean, it is just sort of has a lot of superficiality, but it also has some real incredible language and amazing images. And I don’t know, can you does it does it represent some way or does it symbolize in some way that these contradictions and DPO that, you know, the tension between wanting to be a highbrow writer and a popular writer and all that stuff does. Yeah, OK.

Speaker I think the raven in some way does.

Speaker I think the raven does in some way embody so many of the contradictions we see in Poe’s selfhood, on one hand, the The Raven is this florid, frothy attention getter. On the other hand, it, I think, has something very important to say and something serious to say about human remembering. And our inability to forget it in many ways embodies that tension in Poe between the popular and the erudite, the lowbrow and the highbrow. And so it does seem to me to be an almost perfect encapsulation of that. You can argue that so much of his work does that, I mean, you certainly see that in in his best-known stories, whether it’s the pit and the pendulum or or The Tell-Tale Heart, he wanted me to say something about health.

Speaker Yeah. Yeah. What did you do? You want to get one thing was just a very quick, brief synopsis of the plot, like a sentence or two.

Speaker But then if you could go on to kind of talk about what what it’s tapping into, you know, what is what is poppin and putting his finger on there when this idea of stranger, the stranger next door who just decides to murder you. Yeah, it’s really, I think.

Speaker All right, so just between us, the narrator in The Tell-Tale Heart is the neighbor of this old man, and he becomes obsessed with him and he one night sneaks into his house, into his bedroom, kills is he bludgeoned him as he murdered, stabbed stabs and. Right. OK, I thought I thought it might have been a hatchet or something, but or I thought he maybe he strangled her.

Speaker I thought, yeah, maybe he does strangle him before he maybe.

Speaker Remember he’s got that. Will you just say murdered. OK, he’s got this obsession. But you could just because we actually hear it read. So OK, but we just need a really brief. Sure.

Speaker In The Tell-Tale Heart, we have this character who ventures next door into his neighbor’s home, sneaks inside as this old man is sleeping, takes small steps into the dark of this stranger’s bedroom and murders him there in his sleep.

Speaker And the story has something pointed to say about paranoia and the changing way of living in America in urban environments, specifically where all of a sudden at this time, there was no room that people were now beginning to live on top of one another. There was this sense of encroachment.

Speaker There was this sense of violation of of.

Speaker Trespass. I wanted to say trespass.

Speaker Um, just give me a date, I want to be specific about it, about is the 18 what date to early 1840 in Philadelphia.

Speaker So, you know, it’s like immigrants moving in, not knowing your neighbors. Right. Right. So.

Speaker The story, I think, has something pointed to say about what’s happening in America in the 18 40s, we have this this influx of immigrants.

Speaker We have people living on top of one another. We have what seems to be the encroachment from from all sides, know where to stretch, no room to move.

Speaker And the the psyche, the psyche, what that does to the psyche, I mean, the paranoia of immigrants and start again.

Speaker I think at the same time, there was also, you know, the penny press was catching on. Literacy rates were rising and people were gobbling up sensationalist stories and true crime stories were becoming a new genre. Yeah, I mean, I know some cultural story and say that, you know, crime was always the something talked about from the pulpit in American culture until the beginning of the 19th century or the early decades when crime became something for salacious consumption, for something to sell, papers to sell. You see this in the 1940s or even earlier than that. It started earlier. But I mean, it’s definitely catching on. And it was you know, there were huge numbers of periodicals and a lot of them were thriving on the sensational stuff. And talk to her was kind of so.

Speaker So in the 1940s, new newspapers are publishing sensational stories of crime. And people understood this was one who knew his audience. And so we have that. On the one hand, we have a pure product of sensationalism.

Speaker On the other hand, the story, I think, is trying to say something important about what’s happening in the country at the time. In the 18 forties, we see this massive influx of immigrants. We have the population in the cities booming people living on top of one another.

Speaker This sense of encroachment of of trespass and not knowing your neighbor, who are these people who live around me in the paranoia that that begins to breed? And so PO is doing that is as well. The story. The story, I think, is one of the most potent commentaries we have on the paranoid psyche. Of course. I mean, he does that in the black cat as well. He’s doing it. I mean, this idea of paranoia comes up again and again. You wanted to go into the into the into the premature burial. And this idea of we can maybe segue into that.

Speaker OK, or just as a separate answer, I mean, what. Yeah. What is it about a premature burial? When when I mean, Poe does seem kind of fixated on that. It comes up again and again and the stories.

Speaker What’s what’s the about? I have I have my own I have my own idea about that.

Speaker Just to help us out, if you could say premature burial buried alive, you know, if you just use the words buried alive as well. Of course.

Speaker What we see in post story, the premature burial is probably the most pervasive fear of humankind being buried alive.

Speaker It’s just about the worst thing you can imagine for yourself.

Speaker Why was Poe so fixated on this? What was it about that particular horror that appealed to him? Because he comes back to it again and again, this idea of being buried alive. And there’s a couple of things I think, that are important. Not only that being buried alive is the worst thing that one can imagine for oneself, but all of the ways in which Poe felt buried under the the pressures of of living and buried, beneath the failures of his aspirations, buried beneath the success of so many other writers whom he considered beneath him the buried in debt.

Speaker I mean, it goes on and on. But to be buried alive, literally.

Speaker That’s repellent. Who wants to read about that? Why would anyone want to read about that? That goes beyond the merely sensational. This isn’t a crime story in the newspaper that people find titillating. This is this is something primal. This is something much more primitive and disturbing.

Speaker Why is Poe.