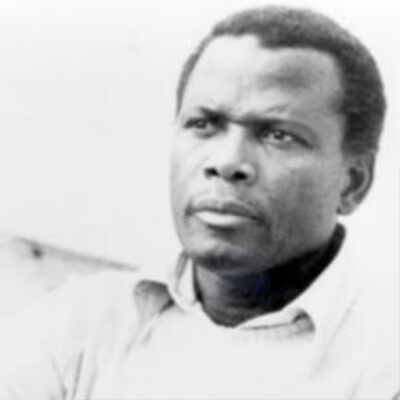

Speaker Why was I sent there?

Speaker I was sent there because my father thought that I had arrived at a point where I had slipped out of his control.

Speaker I was. 13, 14, 15.

Speaker And I was the last of his children.

Speaker He was getting on in years and to hang on to a kid who was running.

Speaker And.

Speaker Living fast with friends and stuff, I was getting into trouble and the kind of trouble that one would get into in the Bahamas and Nassau at that time was the kind of trouble that was punishable by a reform school and reform school almost.

Speaker It didn’t matter how old you were once you got in there. They didn’t let you out until you were 18. So my dad sort of saw me four or five years being put away, and he thought that I should be not exposed to that. So he he wrote to my older brother, my oldest brother, and in fact, he lived in Florida. And he said to him that Sydney is at a place where it’s very difficult to manage him. And I wondered if it would be possible for you to receive him in Miami and try to put him in school because I quit school in Nassau to go to work. I was working at the age of 12 and a half. And I was my my my salary was essential to the family’s survival. And when I was I was not working. I was running with a group of guys who were imaginative.

Speaker And so my dad thought he tried to.

Speaker Salvage me, and so he wrote to my brother and my brother sent him ten dollars.

Speaker With which he took me to the American embassy in Nasr and got for me an American passport because I was born in Florida on a trip he and my mother had made some 14 years before to sell their tomato produce from their farming. He always knew that the accident of my birth in America was could be an advantage. And that’s why he wrote to my brother and said that could you send for him? He is an American citizen and as such, he could get out of this environment that was about to kind of grab hold of him. So my brother sent the 10 bucks and my father got me a passport and he took me down to the boat on the day that I left.

Speaker And he put me on and he said, take care of yourself, son.

Speaker Anyway, I went to to to, uh, to Miami, my brother was at the boat to pick me up. Oh, I was.

Speaker My first impression, I’d never seen things like that, I had never seen ships so big in the harbor, I never seen buildings so tall, never. And in Florida comparably speaking later, later on, I would see buildings infinitely taller than that. But I never seen buildings that tall. And the land area was vast. I mean, it took a long time to get from the waterfront to where he lived. And there were so many people and cars and stuff and things. It was a it was really mind boggling for a kid who had just seen a car when he went to Mass a few years before.

Speaker Everything was new, all kinds of remarkable things were new to me. Also new to me was the.

Speaker The way the society was structured.

Speaker You had segregation in Miami, very intense. Uh.

Speaker You had racial lines and economic lines and class lines, stuff like that, and people who were party to it had all accepted it. That’s the way it was. Whomever was involved in it. That’s the way it was. It had been for for them and it had been for their parents and all the preceding generations that they could remember. For me, it was new, but really knew there was some of it in the Bahamas, but nowhere near as intense as it was in Florida. So, so so when you were delivering, you had a job delivering on the wrong street?

Speaker I ended up not on the wrong street. I ended up on Miami Beach, actually, and I ended up on the correct street at the correct address. I was a delivery. I was a delivery deliveryman. I was a delivery boy. I delivered.

Speaker Medication, whatever was ordered from the drugstore was a drugstore called the the Burdens Department Store, Drug Department something anyway.

Speaker I was sent to my base to deliver this package to this particular house, and I went there and I saw I noted the address and it was the same address as was on my instructions that I walked up and I rang the bell and a lady came to the door.

Speaker A white lady came to the door and she opened it and she said, before I could speak, she said, What are you doing here? I said, I came to deliver this package to you, ma’am. And she said, get around to the back door. I said.

Speaker But you’re here and and here’s the package, and she said, get around to the back door and the door slammed in my face, I couldn’t understand that, really.

Speaker I figured I was a kid, mind you. And I’m new to this new value system. I figured she was standing there. Here I am. Respectfully, I passed the package as it as I was supposed to do. That’s my job, to bring her up and she wants me to go. It was a pretty big house. So around the back was quite a ways, you know, you have to do is accept the package. But that was tradition. And I didn’t quite know that.

Speaker Were you aware of why she wanted you to go to the back door?

Speaker No, I didn’t. You see, that’s what I mean. It was I didn’t know why, but I learned later, that’s the tradition. That’s the value. That’s the way things were done. So not knowing what the tradition was and had I known, I probably wouldn’t have abide by it.

Speaker I thought that I’m here. And here is the package. She didn’t choose to take it. So I sat it at the door, at the front door, and I left. Well.

Speaker Couple of nights later, I go home to my brother’s house. I was out somewhere and as I approached the house, it’s dark, no lights anywhere. And I walk up to the front door and as I went in my sister-in-law, grabbed me and pulled me in and threw me to the floor.

Speaker I don’t know what’s going on. And they were whispering, saying I wanted to know what I had done and I said don’t. But I have not done anything. And she said that the Klan was here looking for you.

Speaker And I said, oh.

Speaker And she said when you were in Miami Beach and, you know, one thing led to another and I explained what situation was and apparently they had been visited, well, it was such a shock to them that I was very quickly my belongings were gathered and I was in the middle of the I transferred to a relative in another part of Miami. And, uh.

Speaker So I went. And that’s where I stayed until I left Florida.

Speaker What was the situation also with that with that sheriff’s group?

Speaker I was in the wrong neighborhood at that thing with the mayor, and there came a time when I wanted not what it had elected, really elected as the only way for me to go to get out of Miami just to get out.

Speaker And I started. I had no, no, no money, but I started trying to take a freight train. I took money and I got as far as Tampa, Florida or Deerfield or someplace up the line going towards Georgia. And I would wake up in the freight train in some boxcar of a freight train that had been that had arrived someplace. And they put it on a sidetrack and there it sat. And I would wake up and I’m on the side track. I don’t know where I am and is not in the city. So I would look for in the direction of where there would be lights coming and I would find some light and I would walk to it and find myself in Tampa or some other place I remembered once. That I was I was picked up by the cops and they took me to this, to the local police station and they called my brother and he acknowledged that he had a brother and stuff and they were satisfied with that and he had to come up and get me. So he came up on the bus and talked me down all the way back to Florida to to Miami.

Speaker He gave me a lecture about his being a father.

Speaker And he has other children and a family and all that. And he has responsibilities and he cannot really attend to my rearing as he would like to.

Speaker And therefore, I have to be more responsible, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker But I still wanted to get out of town. I just had to get out of Miami when I had accumulated enough money, by whatever means. And it was quite legitimate. I worked somewhere. I picked up a few bucks. I had a few items of clothing in a place in a dry cleaning plant. I went to the dry cleaners to pick it up and they said they have not returned. I then decided I want to get out so badly I will go to the plant and get my clothing. They pay for it. And the dry cleaning guy said, it’s OK if you go. And he gave me the numbers that I would give the people there and they would find my clothing. I went to this place. It was dark, it was night was was falling, you know, I got there, they looked for the stuff, it was not ready and they said it was not ready to answer. So I have to go all the way back now and wait another day before I can get out of Florida. So I’m on my way back. But the buses stop running. No buses are running. It’s in a white neighborhood and I am a long way from home.

Speaker Hmm. So I decided that I would hitchhike.

Speaker I waited as long as I could for a bus, and then I found that they were not running. So I kept looking at cars going in the direction of what was then referred to as Colored Town. And every car that passed, I would see whether there were blacks in the car or not.

Speaker If there were, I would some. If they were not, I would wait. And when I recognized an automobile with black occupants, I would come along comes a car.

Speaker And it seemed to me to be black, occupant’s.

Speaker And I started the family and the car came over and stopped, as soon as that stopped, I realized it was a car.

Speaker It was actually a police car, unmarked with four policemen, white in the car. Anyway, they said one guy sitting in the passenger seat front said to me, he said, What are you doing? And I said, I’m just trying to get back to home. The buses are running. He said, You see that, Ali over there? You go up in that alley, go up in the.

Speaker So I went up in the air and they back of the car, I do I have to tell you about this.

Speaker They back the car up and the guy in the passenger seat.

Speaker Roll the window. And.

Speaker His hand came up with a gun and he just beckoned me with the gun like that, and I lean towards the window and he put the gun right there and he started doing that where it is with the muzzle.

Speaker And they started asking me questions. They wanted to know where I was from and.

Speaker Who told me to come over here and how did this whole situation was that I was here after dark and stuff like that?

Speaker Well, I wasn’t as frightened. As would have been to their taste. So the questions got meaner and more threatening and stuff.

Speaker Anyway, they.

Speaker Behind the wheel was, I suppose, the person of authority, because he said the guy with the gun said, what should we do with this kid and then use the word kid.

Speaker And the guy behind the wheel said.

Speaker Let me ask you a question.

Speaker And he said, if we let you go, do you think you could walk all the way home without looking back?

Speaker I said. Yes.

Speaker He said, all right.

Speaker He said, I want you to turn away and start walking home. We’re going to be right behind you. He said, if you look back, we’re going to shoot you.

Speaker So.

Speaker I started walking, I got to the end of this alley that emptied onto this main street where I was hitchhiking and I made a right turn and along the street were stores that were closed, but they had glass windows.

Speaker And by shifting my eyes to the right, I could see reflections of the police car creeping behind me. I was 50 blocks away from where I live.

Speaker And they stayed right behind me. I lived on Third Street.

Speaker And then at Third Street, I turned the corner heading toward the house.

Speaker And the police car accelerated and went on about its business.

Speaker It made me pretty angry, but there is a combination, there is some fear, obviously, but you see, I was not accustomed to being that kind of afraid of white people. I was.

Speaker I was as much angry as I was afraid because I thought that they were going to shoot me, but they needed to do something that would justify the behavior that was in my mind.

Speaker I thought it was an unfair situation, you know, because to treat someone like that, it was just this peculiar.

Speaker Now it would take me years to get to understand how such a value could be cultivated in an adult person.

Speaker I was 15 years old. So that’s what.

Speaker Racism was in America that what segregation had right then what?

Speaker The state of things were in that. It’s a long time in the making.

Speaker And they these cops have no understanding of the.

Speaker Dynamics of their behavior, really, they really didn’t. I suppose they must had must have been trained to behave that way.

Speaker And they have seen other people behave that way, and it had grown to be an accepted behavior under such circumstances so that they could come to it with such ease means to me.

Speaker Amazingly, luckily for me on the other side of the coin, I was not raised in Florida. Had I been raised in Florida, the desired effect would have been instant. You know, I would have I would have been sufficiently afraid, as would have been the expectation. And I would have probably behaved in a manner that I probably would have thought would be expected, you know. But I wasn’t raised in Florida. I was raised somewhere else. And I’ve had and I had time where I was raised.

Speaker To get a fix on myself. So there you are.

Speaker So from Florida, you went to the how did you get to know the. I first went to Georgia to work in the mountains in the summer resort, and I worked there for the summer months, it’s way up in the mountains of Georgia, I don’t quite recall.

Speaker Susan, disconnect the phone, huge, you know, um, yeah, you went first to George, made enough money that I made.

Speaker Thirty nine dollars that I saved. And George, I was a dishwasher in Georgia. I was working in a kitchen in this resort area there. And it was wonderful. I was working as a dishwasher all the way at the top of this mountain.

Speaker And I would come down in the local town at the foot of the mountain where there was a black community, small, and I would get one one day per week off and I would go there and be nice. And then I would go back up and work for another week. And after the summer was done, I had saved saved thirty nine hours I came down. The decision now is what to do, where to go. Certainly Florida was not a possibility.

Speaker I went to the bus station, Greyhound bus station in Atlanta, and I walked up to a ticket window and the lady said, Where would you like to go?

Speaker And I said, where is the next bus going? And she said, The next bus is leaving in ten minutes and is going to Chattanooga, Tennessee. I said, How far is that? And she says, Oh, that’s a few hours or an hour and a half, whatever it was. I said, When is the next bus going? She said, Next bus is going. And I said, How far is that? And she said, That’s two hours. I said, and the next bus. And by this time she’s coming. And she said, Where do you want to go? I said, I don’t know. I said, and then she said, Well, the next bus is going to Philadelphia, the next bus is going to New York. I said, How far is that? And she said, Well, you’re right. All day today and all day tomorrow and whatever I said, I want to go there.

Speaker So I bought a ticket one way and I left for New York. And I arrived in New York with three dollars in my pocket because the much of my fee, 39 bucks, got once one part of it went for the bus.

Speaker But there were other dollars I had in a small little release in my bag in the baggage compartment, and someone rifled through it and took much of the clothing and the few dollars. But I did have three dollars in my pocket. So I arrived in New York with three dollars in my pocket. Happily, certainly. And so what was the impression of the.

Speaker Well. They were ahead to impact.

Speaker From the first ones.

Speaker The people, just so many people and buildings, tall buildings and people were moving on the streets at such a rapid pace and seemingly everyone was in a hurry.

Speaker But more than that, there was another the other impact was I felt.

Speaker At ease, I felt compatible, I felt I felt OK.

Speaker Mind you, that might be coming off of stories I might have heard about New York. New York is in the north. The north is different from the south. I heard stories like that. Harlem was in New York and in Harlem. There was a substantive community. I had heard talk about that. So I suppose I got to New York with expectations that were contrary to what I had experienced in.

Speaker New York was a wonderful.

Speaker Just an extraordinary place, mind you, while New York was an extraordinary place, but it it overwhelmed me very quickly. I mean, it got the better of me. I had some very trying times in New York. Very. Times that I survived, I went to Harlem instantly, I wanted to know how to get there, I wanted to see the place, and I checked my little valise with the remaining items of clothing that I had.

Speaker And I want to go to Harlem.

Speaker So I saw who I saw a black guy going down in a hole and it was some steps going down into the ground.

Speaker And I said, Excuse me. And he said, yes. I said, Could you tell me where? How do I get to Harlem? He says, When you go right down there, you take a train.

Speaker I never knew there were trains underground, you know?

Speaker Anyhow, I went down there and I learned how to put a nickel in the old thing and I took the subway. I have been told where to get off. I got off at one hundred and 16th Street and I was in smack in the middle of Harlem. And I walked around for hours. It seemed then as it got dark, I started looking for a place and I have no idea had never been into a hotel. I never knew what the cost of a hotel was. But I had these three dollars by now, maybe two dollars and 40 cents left.

Speaker And I imagine that maybe I could get a room for a dollar and I went to a place, having inquired on the street, I went to a place and the the cheapest room they had was three dollars for the night.

Speaker So I got back on the subway, I went back down to 40, 40, 50 Street and Fifth Avenue and 8th Avenue.

Speaker And I walked from 8th Avenue to Broadway and 15th Street.

Speaker And I saw the most incredible sight I had ever seen to that point in my life. It was nighttime on Broadway, looking south from Fiftieth Street. And Broadway. The view was.

Speaker There were lights of every color you can imagine, and almost all of them formed images, faces. There was a guy with his mouth open, huge figure of a face, and out of it was coming smoke.

Speaker And there was his his hands near his face with a cigarette 60 feet long, it seemed, you know, and it was smoking and things like that.

Speaker And images of of of creatures and people running around on enormous billboards and stuff like that. I had never seen things like that. I never knew light could be used in such a way. It was it was amazing, you know, so I walked toward it. I just walked down Broadway looking bumping into people, of course.

Speaker But looking at all of this massive display of lights and colors and images and stuff like that.

Speaker And I wound up at 40 seconds of it. And then I turned just right a little bit.

Speaker And Forty Second Street was this massive array on the right and the left hand side of the street of theaters, movie theaters, all movies from Broadway to 8000 movies, movies, movies and people, people, people just off of the corner on 40 Second Street and Broadway was a little milkshake stand.

Speaker And I saw a lot of people just standing there getting milkshakes. I walked up and I noticed that they had milkshakes and hot dogs, so I ordered a hot dog and I ordered a no show and it was so delightful.

Speaker I was so full of enthusiasm and energy and interest. I mean, the excitement was just bubbling in me and I ate my hot dog and I’m walking up, going back up Broadway with my paper cup of of my malted sea.

Speaker I get to Forty Nine Street and Broadway and there is a sign in a window that says dishwasher wanted. I made note of it, but I wasn’t yet ready to release myself from this thing. So I walked up and down Broadway from Fiftieth Street to 40 Second Street and back for about two hours. Mind you, during the walk back and forth, I’m spending my two dollars and 40 cents, so. I wound up busted.

Speaker About I don’t remember exactly what time it was, but I stepped inside this place at 15th Street, 14th Street and Broadway is called the Turf Bar and Grill.

Speaker I walked in there and I said, you have a sign in the window, dishwasher. And he said, oh, yes, and I said, I’d like to apply and he said, OK. He said, come around behind the counter, which I did. He was a barman and he picked up a trapdoor with stairs leading down into the basement.

Speaker I went down into the basement.

Speaker That’s where their kitchen was. And they have this monster dish washing machine and they hired me on the spot.

Speaker I didn’t know how to operate the machine, but they taught me rather quickly. And I worked there all that night till the wee hours of the morning. And because I was relief for that, because I just came in, they paid me on the spot. When I was finished, they gave me four dollars and 11 cents for the night. They had given me two meals as well, and I thought this will be my salvation, I can work as a dishwasher and receive two meals per day or per night. I said that would be really terrific. And that’s what I became.

Speaker I became a dishwasher and I became quite good at it. As a matter of fact, that’s what I did to sustain myself was to wash dishes.

Speaker And what about you sleeping on the building? Well, Miles, you really went into a lot of stuff, into your research is better than mine.

Speaker I slept in an appetite at. The bus station first. Several nights, as a matter of fact.

Speaker And then. Then I went to the rooftop of the Brill Building, it was like having a penthouse apartment. The elevator operators and the people who work there never knew that I was sleeping on a rooftop.

Speaker I would go in, get on the elevator, and I would get off a floor beneath the roof and I would wait till it was advantageous and I would just go up the stairs and out on this rooftop. And at night, the view was spectacular. Obviously, I used to.

Speaker I used to spread the journal American down on the floor of the roof and lay on it. That was my bed. And then the winter started gathering.

Speaker And it was too cold to do that in the meantime, you wonder how I managed, you know, I managed because I was a block and a half from the bus station where I could go into the john where I used to sleep and do my bird baths and, you know, wash up and be prepared to go to work and stuff like that.

Speaker But the winter came and it was very difficult. Was that your first winter in your life? Oh, yes.

Speaker How to tell you about the winter, the winter, my first winter was an experience I had never been ever in my life, in temperature below maybe sixty four, sixty five, ninety nine and nine tenths percent of my lifetime were spent in temperatures.

Speaker Seventy eight to 100.

Speaker And more, but. The winter in New York, that first winter.

Speaker It was it was something I had no clothes, I had I had no gloves, I had no appropriate shoes or socks, I had no scoffs I had nothing. I had some clothing that I wore in Florida, most of which had been stolen on the bus when I came to the. My hands would freeze. My lips would freeze. It’s called what’s called.

Speaker I I saved every penny for about two weeks.

Speaker And I got a room in Harlem for seven dollars a week.

Speaker And I was I was sleeping in the warmth for for a while, but then I couldn’t maintain the rent and I was then back on the street for a while. The winter was.

Speaker A teacher named. Yeah.

Speaker Was it tough adjustment getting used to the seasons? It was a tough adjustment, but you do what you have to do and I did. And in time I, uh, I became OK with it.

Speaker Why was it that you saw the that took place before that, but I saw the ad for the American Negro Theater. I was washing dishes and I was in between jobs.

Speaker And I used to go to the Amsterdam News, which was a black newspaper that is still is, by the way, I used to go to the Amsterdam News for.

Speaker Jobs off of the want ad pages.

Speaker And one day I’m looking at the wide eyed page in the Amsterdam News, which said dishwasher wanted reporters wanted all of those elevator operators and janitors, all those things.

Speaker And over here to the left was the theatrical page. But I never read those newspapers. I never read theatrical pages. When I wanted to go to a movie, I never consulted the newspaper. So I didn’t know what a theatrical page was. And here I am staring at a theatrical page. And the one thing that caught my eye on that theatrical page was actors wanted.

Speaker It was an article about the American Negro theater wanting actors for its new production.

Speaker It did not say actors wanted, we are going to pay you a salary. It just simply said actors wanted.

Speaker I presuppose as if it was a dishwasher. They would pay me a salary. So I decided I’d go take a look, see, and maybe I could do one of those jobs.

Speaker I go I go to this place, the American theater then was located in the basement of the Schomburg collection, the library of the Schomburg Collection at 30th Street and Lenox Avenue.

Speaker I went there with my newspaper and I went to this little door behind the library and I knocked on the door and I said, come in. I walked in and there was a guy.

Speaker A huge man, very imposing looking man, and he said, what can I do for you? I said, I read this thing in the paper about actors worried. He says, Are you an actor? I said, yes.

Speaker He said, OK, come on in here. And he said, Well, where have you been? Acting nice in corporate. And he asked some questions and I gave him very quick off the top of my head answers.

Speaker And he said, OK, take this script, and he handed me what essentially was a book, but it was soft. I had never seen a script in my life. I didn’t know what a script meant. So he passed it to me and I took it not knowing what he would say next. And I waited and he said, go up on stage and turn to page. And he gave me a page number and he said, You will read John. And I read the other part will play the scene. I said, OK, so I go up on the stage with this script and I opened it and I found the page he mentioned and I opened it. And before I could say anything, he said, take a minute. And just the.

Speaker And before I could say anything early and before I could say anything, he said, take, take, take a few minutes and read, read the scene through and let me know when you’re ready. So I said, OK, so I have this script in my hand and I’m reading what I now know is a scene.

Speaker And there are two people. I’m John, I suppose, and there’s another name somewhere. And underneath that name are words dialogue for this other person. And I figured, oh, I got this. Now John is my stuff. That’s what I have to read.

Speaker And I read this thing and finally said, You ready? I said, Yes, sir, that OK. Woo! And he said.

Speaker I took my script and I said.

Speaker So where are you going to follow that? That was the level of my reading. I mean, I had a year and a half and in school in NASA, so my reading was very poor. But I could sort of manage. I could I was taught in the school I went to that you broke everything down in syllables, you know? And so I would always take three words and I would try to get the sound of the three words and then I would put the next I mean, three letters that I would put the next three letters in the next three letters. So my reading came out very halting and very disjointed and absolutely no resemblance to an actor.

Speaker And he hit the ceiling, this man, and he came up on the stage and he snatched the script out of my hand and grabbed me by the arm, spun me, and with this grip on my arm starts moving me towards the door.

Speaker And he’s talking as he’s going. He says, What are you doing? Wasting people’s time on the way to the door. Mind you, he said, why don’t you get yourself a job? And that’s what he said verbatim. He says, Why don’t you go out and get yourself a job as a dishwasher or something and stop wasting people’s time.

Speaker By then, we’re at the door. He opens the door and he says almost like icing on the cake. He said, Amesys, you can’t even speak.

Speaker He was referring to my Caribbean accent.

Speaker Bam, the door slams behind me. First thing that jumps into my mind, I say. How did he know? That I was a dishwasher. What was there about me that made him say, why don’t I why don’t you go and get yourself a job as a dishwasher? Was there something about me that suggested that? And if there was, what was it? He didn’t just it didn’t just come out of his head like that.

Speaker What was it? Why did he and in my mind, I equated his attitude with meaning, a dishwasher is your level. So why don’t you go out and seek your level and find a life. All right. I also said to myself, if if I don’t do that.

Speaker If I find that I can do something other than that. Then he will not have been prophetic. I made up my mind as I was walking to Seventh Avenue 134 Street to take a bus downtown to an area where there were a lot of unemployment office employment offices where I would find a job as a dishwasher. By the time I got to 7th Avenue, I made up my mind I am going to be an actor for no other reason but to show him that dishwashing was not going to be. My life. I went downtown, I got a job as a dishwasher, and my first Muñiz, I bought a radio, a very small radio, not a transistor, as we know in recent years, but it was a small regular radio, a little tiny box radio.

Speaker It cost me thirteen dollars. I took it home to my room and every waking hour for six months, I would listen to the radio because I knew I had to get rid of the Caribbean. Singsong accent.

Speaker Because he had all but told me I couldn’t even speak so.

Speaker After six months. I went back there because I had learned in the meantime that they used to give auditions there, but they had moved to another place, a larger place, had a wonderful theater, was called the American Negro Theater at 127 Street. I went there, found out that they were going to have an audition for new actors to start a new class. And I said that I would like to come in for that. And they said, fine, I looked around for this guy, but he wasn’t there.

Speaker They told me the date. They said, you must come with a scene.

Speaker I didn’t know you could go to a place and buy a book of plays, so I bought a True Confessions magazine and I memorized the first chapter of it, that was going to be my audition. I went to the audition to make a long story short, and I saw the guy.

Speaker He was.

Speaker I owe my life, and his name was Frederick O’Neal, Frederick O’Neal was one of the most remarkable people that I got to know.

Speaker He was a fantastic actor. He eventually became the head of actor’s equity in New York. He was a trained theater person. And his outburst to me was. Almost a comment, quite. The contrary to everything, I thought his his behavior to me was saying I would learn later, I never asked him, but I deduced. His respect for his profession was such that I my, my, my assuming that I could come in off the street and.

Speaker And. Impersonate an actor offended him.

Speaker Yes, offended him.

Speaker And he was one of the people I would have to perform for, and I performed a little my paragraph from this True Confessions magazine at the end of which I make this quick, at the end of which they they didn’t select me, as a matter of fact.

Speaker And I left they informed me later that I was not selected because whatever the reasons, but I was devastated. So but I did notice when I was there that night that they did not have a janitor.

Speaker So three or four days I went back and I said to whomever was in the office, I said, you know, I auditioned the other day. And I was told that I was not accepted. And I thought because I notice that you don’t have a janitor here. I said, I work during the day. Sometimes I work at night. But I can always come by and do the janitor work.

Speaker I said, if it be of interest to you, I would do the janitor work for free if you let me come in and study. And they said, well, I can’t do much about it, but I can pass it on to miss whomever or whatever. So one person led me to another and I repeated the same story and it got to a man named Abraham Abraham Hill, who was one of the directors of that. And he was so impressed with the idea that I would be interested that interested in studying that he spoke to his compatriots. He said, let me let me know in a few days.

Speaker So anyway, long story short, they took me on and I would go early evenings before classes. And I would I would mop and I would clean and I would make things right on the stage and sweep up and stuff. And after classes, I would put out the garbage, such and such as it was.

Speaker And after one semester, they let me go because I they didn’t think I was going to work at.

Speaker And the dramatic the drama teacher’s name was actually. Anyway, one thing led to another and.

Speaker My fellow students came to my rescue.

Speaker They pass the drama teacher to keep me at least till the end of the following semester so I could have a chance to do something with a production, she was somehow impressed with that. And they kept me.

Speaker There were my fellow students in the class that had been collected out of those who had auditioned with me. And then. As we got close to the student production. Everyone had a chance to try out, I tried out, but I was rejected again for the student production and the part that I wanted, a guy comes in a day.

Speaker Interesting, a guy named Harry Belafonte. I never met the man, never heard of the man. I never knew anyone existed by that name until I’m in the basement of the theater organizing some props and costumes and all stuff that had been used in other productions to see what could be used in the new production.

Speaker He came down into the basement and I looked at this guy. He looked at me and we introduced ourselves and he it was very pleasant, very nice, very handsome man. And we had a conversation and that was that.

Speaker A few days later, I found that he had gotten the part that I wanted in the production and which for me was cool because I would get a chance to to learn about things from a guy because he was not a student. He was brought in by the drama teacher and my friends in class. Once Harry had been hired, my friends and class went to her again on my behalf and said, Massata, you know, Sidney could be his understudy. And she said, All right, I’ll give it some thought. And she again said, OK. And I became Harry Belafonte understudy and.

Speaker So history begins and so and so it goes. History, yeah, a long history, so so you went know.

Speaker Yeah. Harry’s dad worked.

Speaker As the superintendent at a building in Harlem and Harry was, as was the custom, I suppose would help his dad to remove in those days, they burnt coal for heating and the ashes used to be dumped in big cans and taken to the sidewalk for the garbage collectors to come in.

Speaker Harry’s job was to help his father on certain days when certain things had to be done at the building and he was not able to make it on a given evening. When I see all the Archer had invited the director who had previously directed the play, we were doing that Harry was starring in, which was called Days of Our Youth. And because it was a sudden understanding on the part of the director and Harry, they were caught short handed. She had previously invited this other director to come and see what she had done with the production. So it was too late to cancel it or make other arrangements. Therefore, she asked me to play the part that night and I did.

Speaker I don’t know how well I did, but obviously it was good enough.

Speaker The guy who that she had asked to come up and see the play was himself about to direct a black version of a Greek comedy drama called Lysistrata.

Speaker Watching the play, he saw something in what I did that interested him and asked me after the production what I come on Monday to his office.

Speaker He’d like to speak with me. He didn’t say why, but I said yes, I would. I did go that following Monday to his office and he said that I’m going to be doing this play. And I wondered if you would read for me part of polymaths. And I said, yes, I would. He gave me a script. Now I know what a script is and stuff, you know? So I read this Polidor and it was a kind of a cute little part, small.

Speaker I had about 10 or 12 lines and I read for him and he offered me the job and they in fact did go ahead with the production. I was able to join Actors Equity. I became an actor. So I went into rehearsals for this job. I just came out of nowhere.

Speaker And the interesting thing happened on opening night.

Speaker On opening night.

Speaker Naturally, there is a nervousness abroad behind the stage.

Speaker I’m in front of the theatre itself and I’m watching all of the people who are with me backstage, the stars and everything. They go up to a little peephole in the curtain and they look out at the audience. I didn’t know it was a peephole. Looking out at the audience. I had no idea what they were doing, but they would go up and they would pick through this little thing. Well, when the coast was clear, I decided to go up and take a peek. What what they’re looking at. I looked through this little people and they’re going through this. I saw twelve hundred people sitting out there in this theatre.

Speaker I had started going, I mean, I get so scared at this point. It’s almost time for curtain, right? And they said places and I got to my place, you know, I knew all the terms now through the rehearsal period and wham, the curtains up and the first few actors, I’m like the third or fourth actor to talk to enter the first few actors.

Speaker They start to play and it’s beginning to unfold. And my turn comes and I can’t help. I got to go out there, but I’m panicked. I got out on the stage and I am out there.

Speaker And while I’m there, something in me couldn’t prevent me from turning my head to the left and taking a look at the audience. I turned and I looked and there again, these twelve hundred people all looking at me.

Speaker I turned back to the actors and I read my line. What I read was not my first line. What I read was my seventh line.

Speaker The actor I gave the to.

Speaker He looked at me as if to say, oh, my God. And he in turn trying to get me back on track. He goes back to the answer he would have given to my first line by now. I know what I’ve done, so I’m trying to adjust. And to that line, I gave him the answer to a fifth line or a six line. Now the audience on my response, suddenly they start laughing. I’m assuming naturally they’re laughing at me. So I get more frightened. And the more he trying to get me on track, the more I go askew. I’m as I’m grabbing four lines, none of which is correct. Obviously, by now the audience thinks it’s so funny and I am crestfallen. I still have three or four lines to go. I don’t know whether I should run off the stage or not, but I stuck it out. Finally, I got to a point where I had no more lines to misrepresent and the audience is falling down. They just having the best time.

Speaker I come off the stage, I go up to my dressing room that I shared with other actors.

Speaker I got undressed out of the costume. It was a Greek tragedy comedy costume. I got dressed in my street clothes and I walked out of the theater.

Speaker I walked to Broadway and then tonight, going uptown, I walked all the way from Forty Fourth Street Broadway. I walked up to one hundred and sixty Fifth Street.

Speaker Bemoaning the tragedy that had befallen the.

Speaker I wandered around in the one hundred and sixty Fifth Street area for quite a while and then about twelve thirty one o’clock, I decided I might as well go back to my room and try to lay my head down and forget about this flirtation with theatre, because obviously it was over at one hundred and forty four street near where I live. There was a newsstand. And at that point, as I was turning the corner in those days, the Daily News used to come by all the big trucks. But the lady was I remember because that’s what I used to read and dump a bunch of papers.

Speaker And the guy who was the paper said he would clip, open the wire and then put the stuff up there. And I said, what the hell? I took a daily news and I took a couple of other papers.

Speaker I was too frightened to even open them. So I’m walking home. And then I figured I better not take them upstairs because the lady was renting me the room and I read it. And I don’t want her to read anything terrible about me.

Speaker So I decided I I’m opening it up and the Daily News, whatever their comment was and then whatever the other newspaper comments were shocking.

Speaker They wanted to know those papers that I read.

Speaker Who was this kid that came out on the stage at the very beginning of the play and absolutely entranced the audience.

Speaker I didn’t know they were talking about me and about me. I didn’t do any such thing.

Speaker Apparently the juxtaposition of the lines appeared to them quite humorously.

Speaker And in a stroke of genius, whoever did it, I got the credit for that.

Speaker I got the credit for wherever I was mentioned in all of the reviews and in those days there were 13 daily newspapers in New York City, 13.

Speaker I don’t know that I got mentioned in all 13, but whenever I was mentioned, it was the most wonderful, delightful response to to the little performance that they figured I had given, when, in fact, I was so scared I didn’t know what to do.

Speaker I thought I had screwed up the whole production. I had I had dared as as Fredrick O’Neal might have suggested, I had dared to imitate an actor. I felt terrible about it. And then these things that these people said, there was something about it that was sobering to me.

Speaker The people who said such nice things in their reviews were unaware of what state I was in internally.

Speaker Therefore, I was not worthy of the comments. But could I become an actor who can engender that kind of response on a genuine basis, go after it and acquire it methodically through skill and the exercise of such talents as I might have, that sort of cemented for me a commitment to self and to the craft to learn it. To master as best I could and to be an actor who knew what he was doing all the time to be aware of if there is magic to be spun.

Speaker Be aware that you’re spinning it or at least be aware that you can reach for that kind of.

Speaker So. That was important. Now, on the basis of that, I continued with the. Did you buy that?

Speaker Means at that time, it was during that period. Obviously, I got to know AC and Ruby, I see Ruby. We’re both with Anna Lucasta at that time and it would be a bit of time before I got to know them as friends. They were either starring in New York or on the road with the play.

Speaker There were several companies assigned Ruby. Bill Graves was an actor. Like, I was new to the game, very gifted, very talented. We became very good friends. I have an enormous respect for Bill Graves.

Speaker He’s a man of.

Speaker Towering strength and what he’s done with his life and his career and his knowledge of film is remarkable. He has, just as you may know, has just finished a, uh, a documentary on the life of Ralph Bunche that I’ve seen. And it is spectacular. Yeah, it is spectacular.

Speaker The other day, their branch branch Bill Branch was.

Speaker A breath of fresh air in the American theater that I knew he was, he wrote a play called A Medal for Willy. It was so wonderful, so refreshing, so imaginative. That’s when I really was first introduced, a bill branch, he was a close friend of Ruth and Jenny piece to.

Speaker Sisters, actually, who were.

Speaker Instrumental in much of my life. Bill Branch, therefore, as well, was instrumental in much of my life and, you know, I’ve come across the years with friends like that Bill Branch, Ruth and Jenny Pace and I can count them.

Speaker As having been there. More than 50 years.

Speaker More than 50 years.

Speaker They were there at the beginning, and today, Bill and I, we mused about the years we carry on our shoulders, you know, and we think about.

Speaker The missteps of youth and. Opportunities missed.

Speaker Which is the best thing you can do for Bill Graves was Bill Graves, was he he was dating Juanita and he introduced me to it that bad step by step, because I married Anita and that wonderful lady.

Speaker We had four great kids. So I think Bill grieves for that. Um.

Speaker Working and starting a family, and you were a baby.

Speaker But how how I mean, what made you want to start a family and and how did you work and make all that? Family. You have to be lonely.

Speaker And. Have survived it. Not by. When we are lonely, we can do something about it. One of the cosmetic things we do is we can place ourselves in situations that anesthetizes.

Speaker The loneliness or.

Speaker Allows you to manage with it.

Speaker There comes a time when I believe.

Speaker Once you are able to manage your loneliness with yourself.

Speaker Then you get a close look at what? Life with another person can and should be.

Speaker Otherwise, you make a big, big mistake, I think, because some people then. Who made the move because fundamentally of loneliness, they find that they are still lonely in relationships sometimes, and that’s because they didn’t work through the long the propensity for loneliness inside, you know, see being alone.

Speaker And it’s different from loneliness.

Speaker Loneliness is a killer, really is. And you can you can work on it.

Speaker Well, having been alone and having been lonely.

Speaker And having survived them both.

Speaker When I got married, I was reaching for what I had as a kid, with my family, with my father and my mother and my brothers and sisters, I was reaching for I was reaching for that energy.

Speaker That was so. Rewarding in my early years. So when I got married.

Speaker First time. I wanted to build a family like that, and I started out doing it for kids. Worked great for a long time, and then.

Speaker Precious. Were difficult.

Speaker And my first wife was quite a wonderful person, quite quite a wonderful person, a terrific mom.

Speaker Wife. And we’re very good friends still, but we had. Different.

Speaker Our comfort zones were at different stations, in a way. She was better able, better able to embrace life at a certain point and say of her life at this point is sufficient for the fulfillment of my life. I respected that, but that was not the place where the fulfillment of my life could have been arranged. I had yet to go another place, so.

Speaker Then when that happens, the person who finds fulfillment at a given level tends to.

Speaker To rest their. I still had anxieties driving me elsewhere. Uh.

Speaker And in our situation, it was not her fault, it was to her good fortune that she found a sense of.

Speaker Of fulfillment at a different point. I was still in the search. And part of the Italian.

Speaker I might have been, might have been. It was. A necessary search for me because the me that I am now. Was in the formative stages. When she found her piece, you see?

Speaker At what point did the first film. First film, first film was no way out, that 20th Century Fox.

Speaker It happened, I was in New York and the rumor has it that a man named Joe Mankiewicz was about to make a phone call, no way out, and he needed some young actors, especially one actor who could play a young intern. And I went like others to see about it to the offices of 20th Century Fox on West Fifty Seventh Street. There was a young man then named Frank. I can’t recall his last name. He worked for 20th Century Fox and I had known him as a nice man. And when I went in, I recognized him. He recognized me. And I think because of that, he put my name down among those to be given a reading and I read and was selected as one of those who would be put on film to be sent to California.

Speaker For Mr. Mankiewicz to see what they did was they didn’t audition me and actually they just put me in front of a camera and I turned around. I turned to the right and the left. I looked up, I looked down and they said just those images to the California word came back that of all the images sent of all the actors, there were four or five in New York that he wanted to see when he came in. He first stopped in Chicago and he saw four or five actors there out of that list. Then he came on to New York and I was calling like the other four or five guys, and he was going to give us a screen test. Each and every one of us and three or four guys had done work for the on their screen test that day before I arrived. When I arrived, they had me waiting for a bit.

Speaker Then I went in and Mr. Mankiewicz said to me, he said, Did you read the script? I said, I read much of it. I was I could I didn’t get the whole thing. He said, Oh, this is well, let me describe it to you. And he gave me a kind of a quick description of the kid. And he said, OK, he said, let’s see what we can do. And I got up there and one of his assistants was reading the other lines, which puts me in mind of the first time with Fredricka. New things were different now.

Speaker And I read the scene.

Speaker And he said to me. Uh, how would you.

Speaker Like to play this part or words to that effect, I said I would like it a lot, he says.

Speaker I don’t know if what’s going to happen, he said, but what are you doing? Are you free? I mean, he asked me some very pointed questions and the issue. And I said, yes, I’m free, he said, so if I choose to have you come out and say, Yeah, well, long story short, he hired me and, uh. I went to California. And that started. I worked for Lassie and Ruby in that picture I worked with.

Speaker But Johnson, Merial, Smith and a lot of other black actors and actresses was my first job.

Speaker That’s how it started first year and that was the part that was the part of the young intern who worked in a tiny hospital in California. He was on duty when Richard Widmark brother comes in, having been shot up in a robbery attempt.

Speaker And he was pretty badly injured. And I tried to save his life that I couldn’t. And Richard Widmark assumed that I had killed his brother for whatever reasons. And so that was the dramatic kind of foundation on which the movie was based.

Speaker And and it was quite an impactful movie. It was different.

Speaker It was revolutionary for its time because it dealt with race pretty head on. Yeah. And.

Speaker Now, now tell the story about the organization that was formed, the protest organization that was formed in Nassau in order to get that film shown.

Speaker Protest organization in that order was formed to get the film screened, you got to understand what NASA was. NASA was then under British rule. Under British rule then was a complimentary way of describing colonialism. While colonialism was a very unfair system to those who were the native colonials whose lives and whose property and whose existence had been usurped by the British Empire, that’s what made it an empire. Britain then was, figuratively speaking, a small body of land in Europe. Its empire came because it had finagled control over India over many of the Asian countries Africa, much of Africa, much of the Caribbean, almost all of the Caribbean, and therefore consequently was her empire. And her empire was administered by its nationals who were sent out to these posts to conduct the business of the crown to the advantage and the pleasure of the Crown. Ofttimes, the advantage and the pleasure of the Crown was not necessarily the advantage or the pleasure of the colonial person that was Nassau. With that being the case when I started in films in America, my very first film, when it got to the Bahamas, there had not been a tradition of a black people coming to the screens in the Bahamas involved on such a high level of realism as that picture portrayed in a in a country where that kind of frank look at race was not allowed because it was too explosive for the colonial value system. So what they did was they banned the movie. They said it cannot be shown there. Was there a a censorship board and the censorship board elected to have this movie, not to enter the country.

Speaker So it was to their advantage to man. Yes.

Speaker And so they did. They banned it. Now, the fact that it was a film in which a local boy was. Very involved. There was some outrage at the audacity of the film board to ban it because, I mean, very seldom was there a film with any black faces in it.

Speaker And ofttimes they were in ofttimes questionable films in terms of what was going on with black people.

Speaker Anyway, there were those many I knew. But then I was a youngster. I was the twenty one twenty four, twenty three or 24 years old, but many I knew of who had positions of authority and they collected together and just really challenged the government and the board and forced them to show the movie.

Speaker Which they did.

Speaker And it was quite a quite an experience there. Well, that was the group that stayed together, that protest against the war to have you the home boy. Yeah, this was the group that eventually in a different form was the one that became the the government.

Speaker The government. Well, yes. Principal principally among that group that eventually became the government was a man named Michael Butler.

Speaker He was a powerful man.

Speaker He was a powerful, powerful in that his values, his attitude to life and his sense of fairness. Fairness was just great, massive. And there were others like him. And you met some of them when you were in Nassau. They decided that the government had to go, that the British government had to go. The only way the British government could go would be to win from it. Independence to win from it. Independence required a lot a lot of brainpower, a lot of ingenuity, a lot of imagination, a lot of courage, a lot of perseverance. And that group, which was the nucleus of the force that ultimately won the government, they were they couldn’t have been better hand-picked, you know, for the job. They really coalesced and they hung in and they worked together and they moved and they challenged and they they nurtured the strength of the population, 90 percent of whom were black anyway.

Speaker But it started it started with the way it started with no way out. And and the members of that party and ultimately the members of the government that that followed were almost all of them were with the exception of Michael Butler and the and the father figures of the movement for independence. Most of them were fairly young guys. Few of them were older than me. Some were obviously, but a few. The prime minister who led the charge, Lyndon pencilling, was younger than than I was. And and he and I grew up a couple of blocks away from each other when we were kids, 14, 15 years old. And and, um.

Speaker And so your mom and your dad saw you for the first time in a film. Yeah, you want to see that? No, I was not there. I heard about it.

Speaker My mom and my dad were invited by the theater owner to watch what what would have to be called the Bahamian premiere. And my dad, my dad and my mom had never seen the movie. Never.

Speaker So it was quite an interesting evening, quite interesting in my mom.

Speaker There was a scene where Richard Widmark, toward the end of the movie, very tense moment, where he going to kill me before he does, he has a pistol. And he started beating me with this pistol all across my head in various places. And my mother leaped up in the theater.

Speaker I mean, she was so carried away by this whole experience. She leaped up into the theater and she sent him back. Sidney hit them back, hit them back here.

Speaker Well, as I’m told, the audience just didn’t know what to say about this lady who stood up in the middle of a darkened theater shouting her bags and hit them back.

Speaker But I can understand, certainly knowing my mother and is that is that when you went back or did you go back before the sun is coming in, what do you think can be done?

Speaker It’s really pushing me behind. Can you see?

Speaker OK, that’s been cry the beloved.

Speaker Indentured servitude resulting court in order to work in South Africa. You talk about the conditions under which you were put in order to work there.

Speaker Conditions, I don’t know that they I was forced under any conditions, the conditions were required by the state, the state of South Africa for the apartheid state of South Africa. But they’re requiring those conditions were not I mean, the problem was not that they required those conditions.

Speaker The problem was mine to decide to work under those conditions.

Speaker And I wanted to see South Africa.

Speaker I wanted to experience South Africa. I also wanted to play that part. Those were the compelling reasons for me. The conditions were.

Speaker To some extent, not that much different from what I knew in the US and in the Bahamas was infinitely more intense and there was a degree of brutality to it that was mind boggling. But it was not unfamiliar to me so that my choice to. Do it to do that part, which was a great part, and to see that country. Was no more difficult for me than it was for me to turn down or accept certain parts that I did accept in the United States to turn down certain parts I did turn down in the United States. It wasn’t an enormous question of. Of morality, integrity, dignity. They were questions, but if I were hard pressed to make a decision based on an experience.

Speaker I’ve had similarities in my life in other places in South Africa.

Speaker What was the actual when they say you have to be indentured indentured at that time?

Speaker My understanding? No, no, no. I didn’t sign any such paper that I recall. I might very well have given the contracts on a film. I might have done so without any knowledge. But that, too, is not the fact, because had they made it clear to me that you are signing this and what you are signing essentially is that Zoltán Kauder will be responsible for your behavior. You are supposed to abide by the rules and regulations of the country. That’s what it is. That’s what it was. But it had a an ominous meaning. You know, it meant that I would not go there and challenge the South African government on the basis of its apartheid practices. I wasn’t going to do that. In any event, I was going there to work on a film. And once I got there, I was smart enough to know that it would have been absolutely ridiculous for me to try to challenge them on that.

Speaker I think the what I came away from it with was an understanding of its reality, a first hand look at how it operated. It was, in fact, an evil system. And to have spent 13 weeks there, I think 11 to 11 to 13 weeks in Johannesburg shooting the movie. I got to know South Africa, as South Africa was certainly from the standpoint of someone of color and the experience was. Educational.

Speaker And Canada is also required, Canada was required to do the same Canada, unlike myself once we were there.

Speaker Canada ignored the rules and regulations, but that was Canada’s nature. He and the things he did to ignore them, I need not go into. But they were quite unusual. I went mostly into the townships, I got to know the people who lived in the townships and how they lived in the townships and what their hopes and aspirations were, how tough life was for them were, how they squeezed their joys out of such hard circumstances and their leaders were who they were. I didn’t get to know their leaders. I met Mandela, I believe, very early in my stay in South Africa. But it was the briefest of times.

Speaker It was at a an ANC function and in the forest someplace. But I ran into people who I would learn later were very important people in the movement, and they were guys who, you know, you worry about. I worry about questions.

Speaker That are actually trivial, comparable to what they lived with day in and day out, you know, their lives were on the line all the time and they could have been killed by a system that had to answer nowhere. Nowhere was there any force that that required them to answer, you know? And I was in the midst of that. I was in that country at a time when they had already decided to exercise whatever means necessary for the survival of the state.

Speaker Canada and I and two other black actors went down there to try to work.

Speaker Canada was a remarkable fellow from Canada, Lee.

Speaker Was a fine, fine actor, refined is the word I was reaching for. He was a free spirit in an unfree world in the way he in South Africa, he exercised his sense of freedom and in ways that I admired. He was very, very, very close to life in the townships, but he was also and insisted on life outside the townships. He was not permitted to travel, but he was courageous enough to travel hundreds of miles from Johannesburg to Cape Town, which was illegal for him to do according to the contractual obligations of.

Speaker He ignored the dangers of the state, he just did it because he felt he had another agenda and that was, you know, at that time in his life, he didn’t live very long after that.

Speaker It seemed as if Canada was saying these years, my sense of freedom, I’ll be in South Africa as I am in the world, I knew what he was what happened to.

Speaker Well, you mean when he came home, when he came home, there were no jobs?

Speaker Which was not anything new, there was there were periods when things were so fallible, you know, that he was left.

Speaker Struggling for survival, the career, too, was its best days had passed. And he was all he was left with was his his sense of himself, which was plenty because it saw him through to the end. You know, I admired him a great deal.

Speaker He was he was his own man.

Speaker And the life was not kind to him in the latter years. He really stood tall all the way he was, and he never you see, one of the things I find very interesting.

Speaker In my life, I try I, I have tried never to be allow myself to be pigeonholed.

Speaker And Canada exemplified that for me, there are guys like Canada who by. By example taught me.

Speaker That it’s better to be your own man. And pay as much of the price as you can afford. Than to be pigeonholed. To be slotted.

Speaker You know, as a person and as a yes person, I know that. Now, let me ask my viability means if it’s good for economics, that’s the.

Speaker As a result, I look at people who got up on the television screen on a show like the Jerry Springer or a show like The Jet, the Jenny Jones or a show like that elderly lady, whatever her name is, Sarah Jessica. Somebody. Sarah, somebody. Oh, yeah.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker Sally, Sara, somebody, right, and there are others, many Maury Povich is one and lots of people.

Speaker And they get Americans.

Speaker Who might be half witted or might not?

Speaker To degrade themselves. In the name of what?

Speaker You’re not recording me, are you there, huh? Yes.

Speaker Oh, no, I wasn’t. I thought you were waiting for this stuff to go. No, no, no, you can’t use that stuff. I can’t.

Speaker You know, absolutely not, because I’m a smoker. Uh, did you get rid of this? Garbage is going to make any sense.

Speaker But it’s a very you know, it is the core of of what’s happening.

Speaker Yeah, but you can’t use or what?

Speaker I mean, I made a documentary called down-And-Out in America, which was the beginning of.

Speaker That was the beginning of an agenda, of course, and all these these stations are owned.

Speaker That’s right. That’s right.

Speaker That’s right. They owned their own. I don’t want to forget it. Let’s get back to our.

Speaker But you’re going to have to talk about it sometime, because it’s it’s. Yeah, what were you doing to support yourself and your family?

Speaker I was working as a dishwasher between films and a little restaurant in Harlem called Ribs in the Rough, a little one that I was part owner of and I was serving food as a waiter. I was preparing the ribs as a cook and I was running the cash register. And I was the the guy mopping the floor is when we closed in the wee hours of the morning. That’s how I set my family at that time.

Speaker The ribs, I thought, were exquisite. I learned from many people later that they were absolutely awful, but that they were friends and they supported the the the the establishment for years. I like the ribs. We had a sauce that I thought was quite good. And they said it was probably something that would cure horses who had distemper or something. It wasn’t widely received, but I had a partner who was a very good cook and a wonderful business person, and his name was Johnny Newton.

Speaker He’s passed away now. He was good at it. He was a restaurant here. Is that the proper phrase restauranteur? He was good. He was good. I miss him. And and then Blackboard Jungle. Yeah, um, this was a big picture.

Speaker Yeah, it’s a big picture. And how will we like jungle? Twenty seven, and you were playing a 17, 18 year old. Uh, tell me about. Tell you about. Well, tell me tell me, um, about that. My question is.

Speaker What about Blackboard Jungle? What’s there to tell about black boys? I have lots of interesting things to tell about Blackboard Jungle, the most interesting of which was the director named Guy named Richard Brooks.

Speaker He was a fine filmmaker. Odd personality. A different kind of a person, he was an oddball, really very gifted as a writer and as a director, I made a few movies for him.

Speaker And we were fairly close. He liked me a lot. He supported me very strongly and defended my right to be a friend of Canada, Liz and Paul, and defended it and. At the studio when they asked questions about.

Speaker About my relationship with her ups and then is kind of a.

Speaker He was there were other things about Blackboard Jungle. I was amazed at the response from people in high places. I remember there was a lady who was the ambassador to Italy, Mrs. Clare Booth. Luce, is that the name? And they thought that the Blackboard Jungle, her position was at the Blackboard Jungle was bad propaganda for the United States abroad. Because it showed a school system that was less than it ought to appear abroad. The picture was not shown in some areas of the South because of its racial mixture and I suppose because of the realistic manner in which the.

Speaker The film problems were dealt with. It was an important film for me in that. It is afforded me a kind of.

Speaker It was good, I was I liked the part and I managed it fair and it was good, it was good for me, helped my career a lot, which was a big, big hit.

Speaker A big hit. And that was your first big. It was my first big hit. Yes.

Speaker Yeah. But, you know, I was not it was not my first big hit in that I was responsible for it. It was a Glenn Ford and. But it was my first appearance in a hit movie at.

Speaker It’s great and so.

Speaker Did you start to pick up interest, started to pick up, yeah, and you started to pick up but interest flagged and picked up and flagged, you know, that’s the nature of the business. There are times when I got one or two calls and then there were times for months and months and months I didn’t that’s when I worked as a dishwasher in between the job opportunities and job offers. Also, I had gotten married and I had young children coming along. So I have to stay busy with some kind of income. I stayed in the restaurant business working in that little restaurant I mentioned to you until I got a call from Richard Brooks to go to interesting to go to Africa to make a picture with him called a Robert Roc’s picture. Something of value, something of value. And that’s when I was able to get out of the out of the dishwashing and the restaurant business. I went to Kenya to make that film, for which it was a very interesting time because the Mamou uprising was in place. It was called the Mamou uprising. But in fact, it was then an independence movement developing in Kenya. Took many, many, many years and a lot of lives for the Kenyans to finally win their independence from Britain. And I was there long before Independence Day. I was there during the height of the the struggle as I was in South Africa when that system was in full force in Kenya. I worked on Mount Kenya, where the Mamou, some people call them freedom fighters, some people depending on your point of view, I suppose. But where they were, they they massed their forces and they dispersed them from that general area.

Speaker And we shot there at Mount Kenya for for some weeks. And we saw SA.

Speaker Actually saw some of the Amabile warriors, fascinating, fascinating, and I worked in Africa many times, many times.

Speaker It was a great experience each time. I mean, it’s such a vast continent and it’s been a troubled continent largely because of colonialism, but not exclusively because of colonialism. I mean, you know, very complex, very complex. The whole difficulties, the whole range of difficulties that Africa endures. Now, some of it has to be sorted out in terms of where all of the responsibilities can be properly placed. And it’s certainly not at any one doorstep exclusively. But it’s a it’s a continent with such vitality, such energy and the difficulties, however insurmountable, they may appear now, I think they are strengthening ultimately in terms of of the future. Well, a lot of those countries. But dictators? Yes, dictatorships, corruption, you know, you look at Africa as Africa is articulated in the and the evening news or in media generally, and you you you you you tend to assume.

Speaker That it has problems that lie outside of those that could ordinarily or would ordinarily be made by.

Speaker That the human personality, almost as if it was some will of some unknown force that found it necessary for such suffering to to to be endured and visited upon that continent, but that is only because there is no time taken to the human personality.

Speaker Sketches, designs. The human condition, there is not a place on Earth where conditions have not been the result of the human personality. Each culture has its mark.

Speaker Each culture has its peculiar fingerprint, but none of these cultures and none of their marks or their fingerprints are without the same kind of representation.

Speaker There is bestiality. It’s experienced everywhere. And that is a part of the human personality. There is a kind of vulgarity to the human personality, however sophisticated it matures as a result of education and refined society. And all that out of it comes ultimately all of them wars and murder and destruction. You know, they don’t come ever out of nowhere, nowhere where they never come out of. They come out of the human personality. That’s how they manifest.

Speaker What triggers it are the ingredients of which the human personality is composed. Greed, envy, lust, the need for power, the need to exercise it, to need to control, and all of those things. There isn’t a society or a culture in which you will find these things absent how we deal with our problems. Like we are a very sophisticated community, are we? Not yet. We are constantly trying to prevent wars and sometimes our efforts to prevent wars create four wars.

Speaker So we need, at least for me, when I take into consideration that long before the present state of things in Africa, we have a state of things in Europe, a state of things in South America.

Speaker We had a state of things in Asia.

Speaker Mind you, all the various cultures that compose these regions within them, you found all of the negatives, every one of them that plagues the world today, that plague the world a thousand years ago, that plague the world a million years ago, whenever and wherever there was mankind, there were these possibilities.

Speaker And they have not diminished at all because they are classic and and inherent in the human personality. Less than what.

Speaker Less than 60 years ago, we were cleaning up World War Two.

Speaker And if you examine that, I mean, some in some views, it was absolutely. It was despicable. What human beings were doing to each other.

Speaker Today, this very day. We’re doing the same things to each other in different parts of the world.

Speaker So Africa as a continent. Is experiencing nothing different than the content. In Asia, South America.

Speaker Our continent here, Europe, no different times may be different.

Speaker Cultural influence may differ, but the basics are always there in old times greed, lust.

Speaker Fear and the need for power, execution, power.

Speaker Power, absolute power. Yeah, and you know what it does. Absolutely, yeah.

Speaker So so when you were there for the second time, you were there and this said something about in Kenya. Yeah.

Speaker There was a situation where they weren’t going to give you a room because you were a black man. And then you remember that?

Speaker Yeah, well, I was making a picture called Something of Value for Richard Brooks. Same guy I had made Blackboard Jungle four and I arrived. All of the actors from abroad had been assigned rooms at the Stanley Hotel, I think it was. And Richard arrived before I did. So I didn’t know anything about this. And he made inquiry at the desk while he was checking. And I was three or four days behind them coming from the States. And he asked about my accommodations and they were he was told that there were no accommodations for me. So he said, why is there no accommodations for him? And they explained what their practices were, which was that in Africa, you know, in an African nation, people of African descent were not permitted in the Stanley Hotel. At least that’s the way it went in those days. And Richard said, well, if that’s the case, I don’t know how many people we are all told, I suspect 100 or more, then we’ll all have to find other accommodations. What are we not? Which obviously changed the whole pattern right there. There was no more of a discussion about that. I was more concerned. I wasn’t that concerned about it, because when I arrived, everything was fine. I went to my room and everything was OK and the dining room was available to me, etc.. My big concern was I knew I was going to work on Kenya. And legend has it that on Mount Kenya, there is a snake called the Black Mamba, which is a very, very deadly creature and I am not too fond of snakes, you see. And I was told that on occasions such snakes could be found even in Nairobi itself, and that they had a habit of if they were near a house, they would take refuge in inside buildings while a hotel is a building, I suppose. And I had to go to sleep in this room. Well, let me tell you, I didn’t sleep a wink. I just kept seeing black mamba snakes fiddling around the posts of my bed so things didn’t work out very well as far as sleeping was concerned and I stayed there for many weeks, I never got over that fear. I’m still not over it today. And I hope they’re not invisible.

Speaker Well, I don’t know whether for that is that they found out how much money you were making to the people who owned the hotel and they decided that you weren’t black.

Speaker Oh, no, that’s that’s not so easy. That. It’s a lovely idea. But I’ll tell you, it’s not the way colonialism works, trust me.

Speaker Yeah.

Speaker I’m going to go back to the story.

Speaker That was that Marty Bell about how he became your agent.

Speaker I don’t know, maybe we did a up on on that day. I don’t know if, you know, we didn’t we didn’t know. All right.

Speaker Are you putting up a flag that shows up? Yeah, it’s squared.

Speaker Tell me tell me about the meeting, Marty.

Speaker Meaning Moneybomb Malibran, my agent, many, many years ago, I got a call from an office in New York, an agency called the Bomb Neuborne Agency, it was Martin Bohm and he said, You don’t know me. My name is Martin Bohm. And I wondered if you would come down and see me. There’s something I want you to go and see about a part. I said, OK, and I.