TRANSCRIPT

(OPTIONAL AUDIO DESCRIPTION)

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -This is one of the sequences in portrait of the artist, which was memories related to me becoming a comics artist and what kind I became.

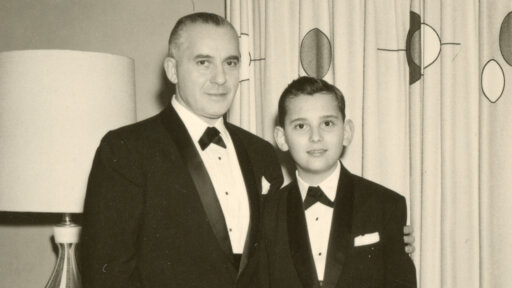

It's a sequence called "Packing, Rego Park, New York City, circa 1959."

"Come, Artie.

Help me to pack for our vacation."

"Aww, I'm learning how to draw Tubby.

I'll help later."

"Don't be always so lazy!

Better you learn something useful!"

[ Sighs ] "I hated helping him.

It mainly consisted of him explaining that I did everything wrong."

"First, we choose what absolutely we need and fold, so the big pieces don't take extra room."

"Uh-huh."

"The shoes you put into the corners with small things in the shoes, and -- acch!

It's important to know to pack!

Many times, I had to run with only what I can carry!

You have to use what little space you have to pack inside everything what you can."

"This was the best advice I've ever gotten as a cartoonist."

-It still holds, then.

-Yes, it still holds, and it was one of the few times I was able to find some kind of rapport with my father where I wasn't at war with him.

♪♪ -Hi, Art Spiegelman.

I'm Barbara Gordon.

-Hi, Barbara.

Nice to meet you.

-Thank you.

-And go on in.

♪♪ -Well... -Thank you so much.

-Hey, thank you.

-Something I've read so many times over the years.

I can't thank you enough.

-Thanks so much.

All right.

Enjoy the day.

-Thank you.

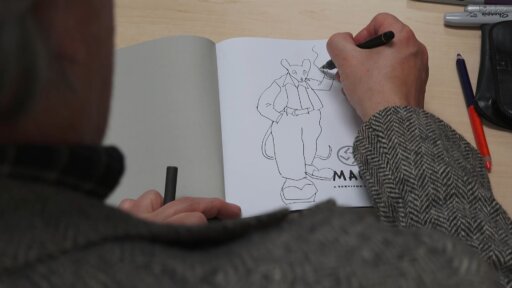

-He's drawing a mouse.

The father.

-Art Spiegelman is the guy that reinvented comics as a medium that people took seriously.

He showed that comics could express the darkest, most tragic, most complicated, most true things about history, about our relationships, about family.

-Because it is comics and it is drawn right from as if you took a pen and put it in the heart and the heart drew this, you can read this difficult stuff.

♪♪ -Art Spiegelman is one of the most important cartoonists in the world working today.

He tackled a subject that was enormous, and he established the medium as a serious literary form.

♪♪ -Piles isn't the same thing as archiving.

[ Laughs ] I've now discovered.

I grew up with just shards of information.

There's such a thing as Hitler, and there's such a thing as World War II.

And there were concentration camps, and somehow, my parents were in them, and they had these numbers on their arms.

And my father would wake up screaming often.

Yet I didn't have a context for all this.

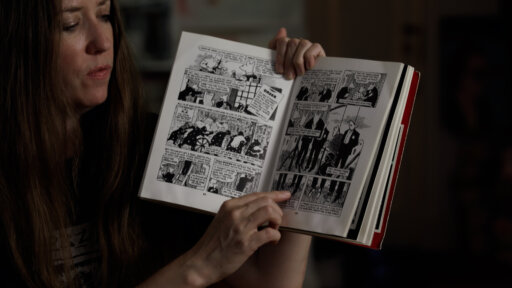

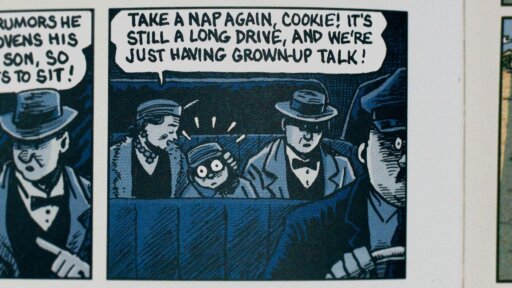

Li'l Pitcher.

"Washington Heights, New York City.

A hired car ride home, circa 1954."

Those little V's represent translated text, was showing that the characters were speaking Polish.

"What a fancy affair.

Everybody was invited, even Janek."

"Yes, but nobody would sit near him."

"My parents always spoke Polish to each other."

"Brr.

Poor guy."

"Huh?

Who's Janek?"

"So the pitcher with a big ear is listening."

"Why don't people sit with him?"

"In Auschwitz, he was a Sonderkommando.

He threw Jews into the oven."

"Why?!"

"If not, the Germans will throw him in the ovens."

"So it wasn't his fault, right?"

"Yah, but it's rumors he put to the ovens his wife and his son, so nobody wants to sit."

"Take a nap again, Cookie.

It's still a long drive, and we're just having grown-up talk."

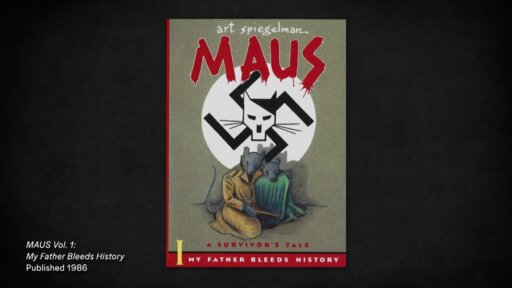

♪♪ ♪♪ -I think it's not an exaggeration to say that of the several truly great works of art that are related to the Shoah, I think there are three that people continue to come back to.

One of them is Primo Levi's novel, "If This Is a Man," another is Claude Lanzmann's documentary, "Shoah," and "Maus," by Art Spiegelman.

It is a work that has not lost any relevance in the nearly 40 years since it was first read.

What I would have known of comics before this was Marvel and DC, Superman and Batman, that kind of thing, but you and "Maus" was coming out of something very different.

The younger Art Spiegelman addresses that point.

Let's watch this first clip.

-Instead of a ritualized story told over and over again, there's such a thing as finding new stories and finding, indeed, what makes a story.

I don't have ongoing characters that repeat from strip to strip, except maybe myself, and it seems like a tradition that's well-rooted in 20th-century art of the artist as hero.

There's actually something pernicious about this idea of the hero being foisted off on, um, kids.

There's these good guys, and there's these bad guys, and they bash each other out, and the good guy is sure to win, and, well, things just ain't that way.

It's fairly simple thing to say, but things just ain't that way.

"Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History."

Trojan Lake, New York, 1968.

"In 1968, my mother killed herself.

She left no note.

My father found her in the bathtub when he got home from work, her wrists slashed and an empty bottle of pills nearby."

"Oy, gott!"

"I was living with my parents, for the most part, as I agreed to do on my release from the state mental hospital several months before.

I had just spent the weekend with my girlfriend.

My parents didn't like her.

I was late getting home.

I suppose that if I'd gotten home when expected, I would have found her body.

When I saw the crowd, I had a pang of fear.

I suspected the worst, but I didn't let myself know."

I now understand that to be one of the central traumas of my life.

But at the time, I was just coming home late, and a cousin of mine corralled me to take me to our family doctor, who was the person who had to explain to me that my mother had just killed herself.

There's ghosts hanging over the household.

She came from a large, closely knit family.

None of it was around.

There was just so much loss.

I think that it finally caught up with her.

[ Indistinct talking ] [ Doorbell buzzes ] Come on in!

-Excuse me.

Pardon me.

-Sorry.

The whole thing's set up in the -- in the most cramped part.

-Where should I put my coat?

-A thing on the other side.

-Can I help you do something here?

-No, just put your stuff down here.

-Just get yourself settled in.

-All right.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -[ Whistles ] [ Humming ] [ Indistinct conversations ] My mother really partially survived because she shared her food.

She didn't care if she lived or died, so she would share it with the other people.

But as a result, the other people there took care of her.

They made sure that she would get through these things.

And she would explain how when she had to take a piss, uh, you're only allowed to piss at certain moments.

And if somebody finds you in the fields pissing, that was a death sentence.

And so what would happen is, the other women would stand in a circle around her and be working there so she could squat down and do what she had to do.

I find this out when I'm a really little kid walking down 63rd Drive to the supermarket, and she's pulling me along, and she says, "I'm gonna have to pee.

I can either make it to the supermarket, or we should turn around," and she tells me that anecdote.

I had no context whatsoever.

-Oh!

Oh, my God.

-Yikes.

-Wow.

-That's why you had to tell that story.

Yeah.

That's right.

[ Dark music plays ] ♪♪ -"Maus" is a twin story.

So it's about Art Spiegelman's father Vladek's experience in the Holocaust.

Another thread of the book is the story of an adult cartoonist who is struggling to visualize the Holocaust in comics form, and is also profoundly struggling with his relationship with his father.

On the indicia page, there's a quotation -- "The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human."

Adolf Hitler.

"Rego Park, New York, circa 1958."

"It was summer.

I remember I was 10 or 11."

"Last one to the schoolyard's a rotten egg!"

"I was roller skating with Howie and Steve till my skate came loose."

"Ow!

Hey!

Wait up, fellas!"

"Rotten egg!

Ha ha!"

"W-wait up!"

[ Sniffles ] Snick, snerf.

"My father was in front, fixing something."

"Artie, come to hold this a minute while I saw."

Snerk.

"Why do you cry, Artie?

Hold better on the wood."

"I-I fell, and my friends skated away w-without me."

"He stopped sawing."

"Friends?

Your friends?"

"If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week, then you could see what it is, friends."

So that sequence was there to sort of frame what happens in the rest of the book, which is a difficult relationship with my father, and one in which nightmare visions drop out of nowhere into my kid life.

-I invest you with the hood.

I will slip it over your head from behind.

-Okay, sure.

Could turn into a murder mystery if you just tighten it properly.

-I have done this a few times.

Let's hope I can make it work.

-So I don't have to worry about moving a tassel from side to side, because it's permanently attached.

-I hereby confer upon you the degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa.

Dean Breslin will invest you with a hood that symbolizes your degree.

[ Laughter ] And it is my pleasure to present you with this diploma.

-Whoa.

Thank you.

[ Applause ] I need to get into my civilian... [ Laughter ] You'd think I'd know how to operate a mouse now that I'm a... [ Laughter ] ...doctor of letters.

I thank you for this honor.

[ Laughter ] And, you know, I was a scholar of comics since I was a little kid.

And, basically, everything I know I learned from comic books.

I learned how to read from looking at Batman and trying to figure out whether he was a good guy or a bad guy.

Then I went on to learn about sex, contemplating Betty and Veronica, feminism from Little Lulu, economics from Donald Duck.

Philosophy -- that I got from "Peanuts."

Politics I learned from "Pogo."

And, basically, ethics, aesthetics, and everything else from Mad magazine.

[ Creepy music plays ] The comic book company is called EC Comics, these first Mad comic books.

They also produced these horror comics, like "Tales from the Crypt," "The Vault of Horror," "The Haunt of Fear."

And people who had an investment in raising children the right way thought this was bad for them.

I, of course, looked at this and saw it as an early secular Jewish response to Auschwitz, of the dead coming back to life, of atrocity taking place in the midst of daily life.

♪♪ My mother took me with her on her chores.

We went into a drugstore.

I was kind of looking at a spinner rack of paperbacks.

There was a tiny little image on this book that was just in a rack, and I couldn't get my eyes off it.

It was only that high, and it was like, "Wow!

That's an amazing, amazing thing."

Then my mother was getting ready to cart us out and I said, "I've got to have this."

And she said, "Absolutely not," because she was on a very tight leash with their spare change and money in my father's household, and I just wouldn't go without it.

And so she let me have it.

And it's kind of the picture that changed my life, because then, as I looked through the insides and found things like a parody of Mickey Mouse called Mickey Rodent, it's like I had never seen anything like that in all my five years, you know?

And it just became a touchstone for me, and it sort of decided that whatever these -- There are people that do this.

I want to be one of the people that makes this kind of thing.

That cover was the cover that launched a thousand misbegotten thoughts and brains.

[ Silverware rattling ] [ Indistinct conversations ] Both of us were warped by a very specific cover of Mad.

-Which one?

-Number 11 had it covered by Basil Wolverton.

-Oh, okay.

-Was the one where there's a drawing of, like, Lena the Hyena kind of character, against a photograph of the building.

-It's made to look like a Life magazine.

-Oh, yeah.

-The Mad logo's in this red rectangle, just like Life.

And I thought, "Oh, my God.

They're making fun of Life magazine in this most wacky, goofy way."

It was just completely, you know... -Shocking.

-Put a big crack in my world.

-Me too.

-This, of course, was the very first issue of Mad magazine.

Started off as a comic book, which, uh, a lot of the readers don't realize.

-Harvey Kurtzman was a cartoonist, a comics writer, and an editor, and invented something profound and important in the world -- the style and humor of Mad.

[ "It's a Gas!"

plays ] ♪♪ -♪ It's a gas ♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Burps ] ♪♪ ♪♪ -Basically, the message embedded in it was, "The whole adult world is lying to you.

And we admit, we're adults, so good luck, kid."

So it basically was asking you to deeply question things, and I believe it was an important aspect of what led to the generation that protested the Vietnam War.

By the time we moved to Queens, I was about 9 years old.

In my parents' bedroom, there was a large blow-up of a very small photo they had of my brother Richieu, and it was there all the time.

So I knew I had a brother who didn't survive the war.

Richieu was about 4 years old, in a ghetto with my mother's sister, his aunt, and when the ghetto was being cleared out and the people were being sent to Auschwitz, Tosha, my mother's sister, poisoned her own children, Richieu, and herself, rather than let them go to the gas.

My parents spent a lot of time after the war looking for him because they couldn't believe he had been poisoned.

I knew he was a good-looking kid, but I didn't know much about him.

And the implication -- I don't remember it being said in so many words -- was, "Oy."

[ Laughs ] "We had a kid.

He was fine.

What do we need this one for?"

-When I was growing up in the -- in the '50s, the term "Holocaust" did not really exist.

You know, that was never mentioned in school.

I knew a lot of that stuff from my mother, who had -- who had had relatives who, you know, were able to, like, get out of Vienna.

But this was not really something that people talked about.

And I think that, for a lot of people, this is why the Eichmann trial was so important.

-The Germans went from one house to the other and took the Jewish men from their homes.

They didn't care how old they were.

My father, too.

They loaded them onto a truck and drove them away.

I ran after them into the woods.

All the Jews who had been taken were already dead.

My father was also dead, shot many places.

-And that was the first time I was getting a sense of some more textured detail about what my parents had gone through.

And, um... it's when I'd hear my father talking about passing through Mengele for the selections.

So they were kind of glued to that.

Sometimes we'd watch it at our house, sometimes with other survivor families.

-He was 13 in 1961, and this was a global televised event.

After he watched the Eichmann trial, he went looking in his parents' bedroom on their "forbidden" bookshelf.

-And that forbidden bookshelf, of course, like, was catnip for me.

And so it included things like "Lady Chatterley's Lover" and a book called "The Black Book," which had some photographs in it that were incredibly disturbing.

There were small booklets that came out after the war giving aspects of the Jewish disaster in various towns and cities.

Books with little drawings by survivors.

That was very, very vivid for me.

♪♪ I started making comics, first copying others, then using joke books to get jokes that I would illustrate in comics form.

When I was about 11 or 12, I was getting published in, like, children's magazines.

There was a local paper in Queens that published a little column that says, "Budding artist wants attention."

Maybe two years later, I went back and got a job at The Long Island Post, and soon I was doing stuff for my junior high school paper, then editor of my high school paper.

♪♪ ♪♪ I'd been doing some drawings for Paul Krassner's Realist magazine.

I started working for fanzines like Wild!

and Smudge with my friend Jay Lynch, who was a seasoned veteran two years older than me.

We were being published in purple ink on these very inexpensive copying methods and finally started my own called Blasé.

And at the time, I was fixated on artists that are still important to me to one degree or another, which is the core of the EC Mad gang, which was Jack Davis, Wally Wood, and Bill Elder.

At some point, I'm looking at a baseball card and realizing that the tiny drawing on the back with the stats was clearly Jack Davis, and I went, "Gee, I'd love to have something by Jack Davis to look at an original of."

And so I call up, and they put me through to this guy, Woody Gelman, who's the head of the Creative Development department.

I mentioned that I'm doing this amateur magazine called Blasé, and I'm going to the High School of Art and Design, and I want to be a cartoonist.

And he says, "Well, you know, why don't you come down?

Bring me a copy of your magazine, and I'll give you a couple of those baseball-card drawings."

So I cut school, and I went there as soon as I could.

He took me to lunch in the little lunch commissary of Towson, started talking.

I gave him my magazine, we had a very long lunch, and that was pretty much the end of it until I turned 18.

And at that point, a letter comes in the mail from Woody Gelman asking me if I would like to get a job working for Top Scum.

It turns out that Woody had kept the Blasé and had clipped a piece of paper to it, saying, "Call this kid when he turns 18."

He asked if I wanted to work there.

I really wanted to do that, but I had to tell him, "I have to go to college, otherwise I'm gonna get drafted.

He said, "Fine.

Just work for us for the summer."

And so I did.

I saw that they were doing another series of funny Valentine cards, things like, "Your teeth are like stars," you flip it over, "They come out at night."

I said, "Can I try some of those?"

I had the thrill of seeing the finishes done by Wally Wood, who was another one of the Mad artists.

This was really exciting for an 18-year-old me.

And Woody just became my surrogate father, you know?

[ Camera shutter clicks ] All through my trying to figure out what kind of cartoonist I could be, Topps Bubble Gum was my Medici.

I worked at Topps from 1965 as a summer job to 1986.

And so it gave me a gig whenever I wanted it.

♪♪ I do have a strong memory of Art's dorm room at Harpur College, later the State University of New York at Binghamton.

And he had his comic books there.

And so I remember going there and smoking pot and reading "Doctor Strange."

[ Psychedelic music plays ] -I had written a paper for my Art 101 history class.

I analyzed the story called "The Master Race," by Bernard Krigstein.

It was singular.

The Holocaust was, on any level, was just not a serious subject in comics.

And all of a sudden, there was a story taking it very seriously, presented in a comics language that wasn't like any other comics language I knew.

When he was trying to show something whisking by and moving, he wasn't using speed lines.

[ Punch lands, bricks crashing ] He was using "Nude Descending a Staircase" as a model of how to show movement.

So he was just inventing, wholesale, a new set of vocabularies that could be applied to comics, mind-blowingly.

I'd done a long paper explaining how significant this was.

An underground filmmaker, Ken Jacobs, who was teaching at Harpur College, saw this piece and sought me out.

-Of course, Ken loved the idea of underground comics, and so they hit it off right away.

-He was smart as can be and profound, somebody who felt things very deeply.

-"Avant-garde filmmaker Ken Jacobs, the high school dropout who became a distinguished professor at SUNY Binghamton, my mentor and irascible best friend for over 30 years.

He taught me how to look at art and to see myself as some sort of an artist."

-He was basically getting me past my slob snob self of being willing to concede that art might exist in museums as well as on newsprint.

-"Stop being such a slob snob art.

Just think of the paintings, the giant comic panels."

"Oh."

-As I was open to it, certain painters struck me as having a family resemblance to cartoonists.

Max Beckmann and George Grosz seemed like they were no different than Jack Davis and Bill Elder, in some ways, you know?

[ Applause ] I feel like I'm, at last, finishing off one of the world's longest standing incompletes.

[ Laughter ] I never even finished my undergraduate studies and therefore never got to sit anywhere near where you're sitting now.

While I was still a freshman, I inherited the editorship of Harpur's humor magazine.

When it was delivered to the printers, they confiscated the boards because they considered some of the cartoons I had drawn blasphemous.

I had been on the Dean's List.

I had also been on every psychedelic substance that found its way into the tri-state area in those wonder years called the '60s.

[ Cheers and applause ] And I left not in a blaze of glory, but in a blaze of ambulance sirens and flashing lights.

♪♪ I was convinced I was God, and Harpur's school psychiatrist thought I should do some advanced theological studies at Binghamton State Mental Hospital.

What happened to me the winter I flipped out was that I had gotten the bends.

I had surfaced too quickly from the overheated bunker of my traumatized family, into the heady atmosphere of freedom and possibility offered by this amazing place at that amazing time.

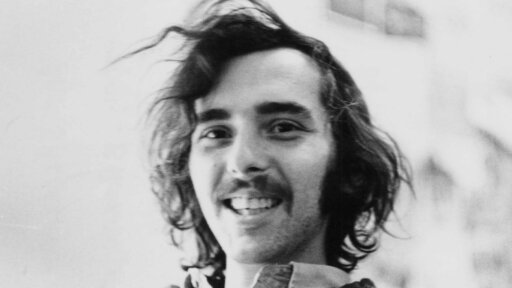

♪♪ ♪♪ -It was 1968, the Lower East Side, and we were taking a photo shoot.

What I thought of at the time is a little old Jewish man in a long woolen coat came over to watch us.

And it turned out, of course, that he was a little young Jewish man.

He was Art Spiegelman, and he was 21.

He gave us a photocopy of his comic, and I said, "I do comics, too!"

-We became real friends at that point, and it launched me into being one of the underground comics set.

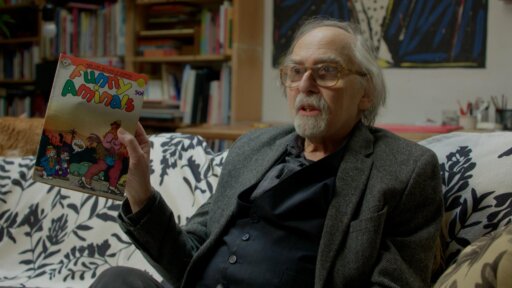

♪♪ ♪♪ I had done "Maus" originally as a three-page comic strip for an underground comic called "Funny Aminals" in 1971.

The only requirement was that it use anthropomorphic characters.

At the time I was trying to figure this out, I went to sit in on some classes of Ken Jacobs, showing some old animated cartoons with cats and mice romping around, and then he was showing some racist cartoons from the same period, and it became clear that there was a connection between the two.

At that point, I said, "I have it.

I'll do a comic-book story about the Ku Klux Cats and lynching some mice, and deal with racism in America using cats and mice as the vehicle."

And that lasted about 10 minutes before I realized I just didn't have enough background knowledge to make this thing happen well.

And instantly thereafter, the synapses connected, and I realized that I had a metaphor of oppression much closer to my own past -- the entire Nazi project, the Final Solution, ended up dividing humanity into various species.

What was involved was the extermination of the Jews, and "extermination" is a word reserved for vermin.

It's not what happens to people.

It happens to people as they get murdered.

This is an underground comic that came out in 1972, "Funny Aminals."

I was in it, and it was very important to me because the cover was by Robert Crumb and he was the god-king of underground comics, setting that whole medium and idiom in motion.

But it had other great cartoonists in it, as well.

So it was a gathering of a tribe.

It starts, incidentally, with a drawing based on a photo by Margaret Bourke-White that was the prisoners at Buchenwald being released in Life magazine.

And that photo is quoted here with the mice.

And there's a little arrow toward one of the mice in the second row that says "Papa," and it's all framed as being in a photo album, so I'll read it to you.

Uh, "Maus."

"When I was a young mouse in Rego Park, New York, my papa used to tell me bedtime stories about life in the old country during the war."

"And so Mickey Die Katzen made all the mice to move into one part from the town.

It was very crowded in the ghetto."

"Golly."

"It was fences put up all around.

No mouse could go out from the ghetto.

No food and no medicines could go in.

They treated us like we were insects.

Worse!

I can't even describe.

"Psst!

You want a potato to buy?"

I was really proud to be in this comic when it came out, and I realized I had crossed the Rubicon into a different area of comics-making.

I would say this is the end of my juvenilia and the beginning of whatever comes after.

♪♪ I found myself moving out to San Francisco.

♪♪ The San Francisco underground comics scene was, like, something really new, fermenting and exploding.

♪♪ ♪♪ About a year before I got to Topps Bubble Gum, Crumb was going to the same offices in Brooklyn.

Woody found out I was going to San Francisco.

He said, "You might want to look up Robert.

Like, he's a good guy."

So I took his address and went to see him.

This was shortly after Crumb's LSD trip that changed his approach to comics and his life.

We started talking about Woody, about comics and stuff, and then he said, "Do you want to see the stuff I've been doing?"

and he showed me the pages of Zap that hadn't been published yet, and they totally blew me away.

♪♪ Seeing Crumb's work was a kind of revelation.

Crumb brought that blue-collar, crosshatched, gritty style back that harkened back to the comics of the '20s and '30s, but, also, much more importantly, began to discover and show that comics didn't have to have punch lines and they could be about anything.

♪♪ -Robert, in effect, took comic books from the industrial place where they were, which was aimed mostly at children, and brought it into the world of grown-ups and into the world of the cartoonists as artists.

So we were trying to make comics that were the work of artists, the work of people wanting to express themselves and do it completely uncensored.

For me, it's always the printed book is the finished thing.

I don't care that much about the original art.

You know, it's different from fine art, where, you know, you see a thing on the wall and the original art.

But to me, this is the finished art.

And I always -- was always a big thrill to see the printed book.

That was this great moment when the books arrived, you know, and you got to see how it actually turned out in print.

Sometimes you see, "Oh, no, the colors aren't right.

The registration's off."

-I was happy if the page order was right.

Ron Turner, they used to get the page order wrong a lot of times.

I couldn't believe it.

Oh, it's terrible.

I met Art at the San Francisco Comic Book store on 23rd Street in the Mission District, which was where I met pretty much everybody.

We went to a little lunch place a few blocks away.

That eventually became the cover of "Short Order Comix" number 1.

So within -- I don't know, within an hour of meeting, we were already plotting to put out comics together.

Art and I are the characters in this six-panel comic.

And Art says, "I tell you, Griffy, comics are this year's Hula Hoop.

If we play our cards right, our mag will be in every dentist's office in the country."

And I say, "Yeah, right!

But what do you say?

Let's blast a few ducks, huh?"

"Sigh.

Deadlines, deadlines, deadlines!

An editor's lot is not an easy one."

"You're all wound up, Art!

Relax.

Frisco's got everything.

After this, we go for a cable car ride."

Art and my personality are pretty clearly illustrated here, I have to say.

-Yeah, we ended up creating an underground comics manifesto.

"It is the Artist's responsibility to hate, loathe, and despise formica.

Comics must be personal.

It is the Reader's responsibility to understand the Artist."

"Gibber-gabber-blort!"

"It is also the Artist's responsibility to understand the Artist.

Mental instability is a tool, and it must be kept well shortened.

Comic books are their own lesson.

We serve no master.

Efficient and callous capitalist exploitation must be condemned and deplored at every turn and replaced by inefficient and humane capitalist exploitation."

♪♪ ♪♪ We were all kind of worried about making a living out of doing our kind of comics, but Art always seemed to be okay with money.

So, one day, he asked me, "How would you like to work on Wacky Packages with me?"

So Art had created Wacky Packages, which were parodies of consumer items.

They were little stickers that came with a square of bubble gum, sold by Topps, and they were a huge hit with kids.

I said, "Okay, um... Well, what do I do?"

"You take a product, put it in front of us on the table, and try to think of how to make fun of it from the perspective of a 7-year-old boy."

This was a very low form of humor.

Art told me the way to think about working for Topps Bubble Gum was that you have to realize that children, at an early age, go through three stages that you have to commercialize.

The first stage, when they're very little, you can describe by the word "hello."

They just, "Hello.

I'm here."

Kind of benign.

The second stage, as they get a little bit older is, "I'm great," when they develop an ego.

That's really prime Wacky Package age.

And the final stage, which comes a little bit after that, is "Fuck you."

So, "Hello, I'm great, fuck you," describes the market for Topps Bubble Gum products.

♪♪ ♪♪ -I was working on a really terrible comic for Short Order called "Just a Piece of Shit," about a talking turd, trying to be one of the, you know, real underground cartoon boys.

And it was awful.

I was living with Michelle, who I think you knew.

-Yeah, I remember her, yeah.

-So she said something that triggered me to, like, start screaming at her and slam the door to my studio room.

And then I realized that that was pretty stupid.

She didn't do anything, you know?

So I went out to apologize, and I said, "Obviously I'm angry.

I have no idea what I'm -- Oh, yeah, I'm angry about my mother."

And then all of this stuff that had happened like about four years before came flooding back.

'Cause if somebody asked, I'd say, "My mother killed herself," but I didn't remember any of the events around it.

They'd been cauterized.

And so at that point, I, um -- I just started writing it all down and then figured, "In order to understand it, I'm gonna have to draw it."

♪♪ And that led to "Prisoner on the Hell Planet."

I'd been looking at a lot of woodcuts, very anguished and expressionistic style, and they had kind of literal gravitas.

They're engraved images.

And so scratchboard allowed me to do something like a woodcut, but without getting my hands bloody.

I found it was a good vocabulary to work in for that particular piece.

-In 1976, I met Art because I got "Prisoner on Hell Planet," and that blew my mind.

I just was, like, so, um, moved by it and curious about it.

I didn't understand how someone could be so intimate on paper.

It was mind-blowing, like, in a way that really opened up so much new territory for me.

You know, when you read something that's meaningful for you, it does bring you into the psyche of the person who has written it.

I had never experienced this to that extent, um, and certainly never in a comic.

[ Camera shutter clicks ] I did something which I never did at the time because my language was very poor and I don't like the phone, but I called him up.

-When she read "Prisoner on the Hell Planet," she was deeply and genuinely shocked by it.

She didn't understand how somebody could make something like that and even express anger at a mother who had suicided.

-I -- I asked him, how could he talk about things that were so private?

-I do remember that it was relentless.

It was like, "How could you say such a thing about somebody who died?"

I said, "Well, I don't know.

Like, I was angry, and I was in turmoil," and explained how I first recovered that as a memory.

-You're showing, you know, your father and the despair and your father climbing on the coffin, and other people accusing you of having a part in his mother's suicide.

You know, he's supposed to feel guilty.

And the fact that he turns the table on his mother where he says, "Well, Mom, if you're listening, congratulations.

You've committed the perfect crime.

You put me here, shorted all my circuits, cut my nerve endings, and crossed my wires.

You murdered me, Mommy, and you left me here to take the rap."

Like, you're -- you're in jail.

Like, you're in a mental jail.

And then he has, "Pipe down, mac!

Some of us are trying to sleep!"

so he actually ends on a joke.

I mean, it was so layered and so intense.

And the conversation lasted hours.

[ Laughs ] And that's one of the things that got us to actually spend time together.

♪♪ -Autobiography had been entered directly as a possible genre very late in the game.

It was part of the underground comics world.

Really confessional, problematic memoir and autobiography came from Justin Green, a comics artist who was a good friend, who more and more was using things that can't be said clearly about himself.

And it culminated in a masterpiece called "Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary."

-It was like 36 or 40 pages, and it was turning each of these little panels into confession booths, dealing with the psychosexual guilt and the obsessive compulsiveness that came with his brand of Catholicism.

-Justin's work showed me how something really personal and truthful could be so powerful.

Showed me a way that I could write a story.

-The thread that ties most underground comics together is transgression, and transgression as a kind of liberating force.

So by showing in your comics stuff you're not supposed to show, stuff you're not supposed to deal with, that the culture outside is telling you, "Don't go there," by doing it, you're robbing it of its power.

-Okay.

Here is a folder called "Art Spiegelman."

This is just many, many pages of tiny little scribble from Art.

He would tell me of his progress on whatever he was doing.

So while he was doing it, he would tell me, you know, how many times he had redone the third panel on page three, and he would just go into great detail?

"I wish it was going faster.

I'm suffering hot and cold running anxiety attacks in my championship game of Beat the Clock.

It's all he cared about was his comics.

It was hard.

To sit at the drawing table is like pulling teeth for Art.

It's torture.

Look at the cover of "Breakdowns," with the drinking the bottle of India ink.

It's not a joke.

It's a statement about anxiety and suicide.

♪♪ -I was just back in New York from my San Francisco days, and I didn't want to let my father know I'd moved back because I'd have to go over there, and I was, as a result, staying in touch with him, using a trick I'd learned from Dick Tracy's "Crimestoppers' Textbook."

And I learned that if you put a towel over the receiver, it would sound like a long-distance call.

Then, for Thanksgiving, I certainly wasn't gonna go out to Rego Park if I didn't have to.

So I called Françoise and asked what she's doing for Thanksgiving, and she said, "Thanksgiving?

What is that?"

So I said, "Well, it's a custom in America where you go to Chinatown with somebody you like.

Would you be interested?"

So that's when we became an item.

-He was incredibly charismatic, and he was passionate.

-When she came over, I began pulling things out to show her.

-He was showing me "Little Nemo," and then not just reading me all of the balloons but explaining the architecture of the page and the choices made by the artist.

I had the impression that he had discovered, like, a new land.

[ "Perpetuum Mobile" plays ] ♪♪ It was like, "My God.

Like, everybody should see this and know this."

♪♪ -It was around that time that I was planning on giving a talk at the Collective for Living Cinema, which was my history and aesthetics of comics.

It's too grandiose to call it the theory of comics, like the quantum theory of the world, although I did take comics very, very seriously, and I thought they were time turned into space, a perfect container for memory, and an incredibly maligned art form.

And without being pretentious about it, I thought that this was as valid as anything that happened in literature or in painting or in cinema.

But I was interested in the fact that comics tended to be simplified drawings, icons.

It all comes from a dictionary definition of comics are a narrative series of cartoons used to tell a story.

The dictionary definition had a picture of Nancy in the side.

The fact that they used Nancy had something to do with the iconic nature of comics drawing.

From there, began thinking more about what a comics page was in a more articulated way, things I'd learned from looking at my masters, like Harvey Kurtzman, at that time, Will Eisner.

and it led to the work and breakdowns where I was deconstructing the language of comics consciously.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -I stumbled upon an anthology of his early work.

called "Breakdowns," which really blew my mind.

The story "The Malpractice Suite" took panels from the very square daily comic "Rex Morgan, M.D.," and cut them up and expanded the drawings outside of the parameters of the original panels.

And somehow, Art had taken the thing that Mad might do where it would make fun of an existing comic, but instead of redrawing it, he took the original panels and expanded them out and blew out the story.

-Art was such a student of the medium that he's able to build on pre-existing work, but to comment on it at the same time.

Similar in a way, to somebody like Jean-Luc Godard, who understood film history as a text that he could revise, he could elaborate on, he could derange, he could criticize.

That's true with Art and comics.

-He was working on this book, and he was conceiving of this thing of color separations.

And he explained to me the basis.

And then, I discovered a whole new level of this, which had to do with the production, because color separations were done by hand, by cutting Zip-A-Tone.

It actually isn't in color until it's printed, so you have to conceive of it in black and white.

I loved that.

I loved how abstract it was.

And I love this work.

I just saw it like, "Okay.

Here is the image, and then here is putting together the blue and the yellow plates, cyan and magenta plates, the magenta and the yellow plates.

And then he starts playing.

And there's so, so many jokes and so much information.

I found a connection that really worked for me.

-When I met Françoise, she was playing hooky from the Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she was studying architecture.

And she was supporting herself in New York, working all kinds of odd jobs, ranging from electrician and plumber to cigarette girl in Grand Central to acting in a Richard Foreman play.

Eventually, she said she was interested in books, and I said, "Well, why not publish?"

So she went out and learned how to print, and we soon had a printing press in our loft.

[ Camera shutter clicks ] -This is some of the things that I could print on my press.

♪♪ I set up as a small business, Raw Books and Graphics.

♪♪ We ended up having to get married because of Immigration.

They were gonna deport me.

-I was really against it because we were getting along great, and I just thought that this would completely destroy our relationship, because I thought that, at the moment that we were married, I'd have Dagwood Bumstead tufts of hair implanted on each side, that she would be given, as a wedding gift, a rolling pin like Maggie's in order to whack me over the head.

The idea of being married seemed, like, irreconcilable with having a lover.

We went down to City Hall and had a shotgun wedding of sorts.

Marriage number two took place when Vladek was informed that we were married, but it wasn't a marriage he could accept because she wasn't Jewish.

Françoise had no problem deciding to convert because it was meaningless to her, but she knew it would be meaningful to Vladek.

She's a much better person than I am.

I was just going, "He has to get over it.

I mean, religion just isn't important to me or to you."

She said, "No, no, we can do this."

♪♪ -I actually got along relatively well with Vladek, and I understood that it was unbearable for Art.

He wanted to do an expansion of what he had done as a three-page strip, "Maus," and at that point, he needed to talk to his dad.

-It was a generation canyon between us.

He grew up in a milieu that was more like 18th or 19th century shtetl life and then went through the central maelstrom of the 20th century.

And me, I was listening to rock 'n' roll and reading Mad comics.

As an adult, I just had no relationship to speak of with him.

Kind of wanted one, wanted a way to come to terms with him, and this book afforded that by giving me the relationship of interviewer and interviewee to replace son and father.

-We knew that we were going to Auschwitz.

-You knew that Auschwitz was a death camp.

-Yes.

But we knew that we would go there and will not come out anymore.

This we knew.

That they will gas us and burn us and all.

-Did you know about the showers?

-Yes, sure.

We knew everything.

-Everybody knew about that.

-The war started in 1939, and this was 1943 already.

And we knew everything what was going on.

♪♪ -A lot of the early part of Vladek's story, as I got it on tape, was told to the accompaniment of him on an exercycle, and that image really stayed with me, of him pedaling madly to nowhere in order to survive.

So I found that a wonderful way to start the story, in the wheel of the exercycle.

And although it's subliminal, I think, in a way, you get to see an analog to a cinematic effect of a whirling wheel, where Vladek begins to spin his yarn and you enter into the past for the first time through that wheel.

-This page is showing the scene of testimony, and it's showing Vladek's entire body across panels and yet disarticulated by these panels.

This ability that comics has to show us a large image, but to fracture it gets at that sense that Vladek is a fractured person.

He's a survivor, but parts of him haven't survived.

In this panel, we see Vladek's arms on his exercycle, and he's framing his son, who looks very small within his arms.

So there's something about that posture in that drawing that's evocative of their relationship.

And I think that's evocative of how Vladek makes Art feel small, not only in his sort of difficult personal manner but also in the sense of encountering history.

-It was a complex relationship that I had with my father in his decline, as he was an old man.

I interviewed him and re-interviewed him from 1978 till he died in '82.

So as soon as we'd finish, I'd make him go over the story again to get more details.

♪♪ I had never heard my mother's story fully.

It's a horrible absence, in that my mother, when I was growing up, showed me diaries always meant for me.

She said, "You may not be interested in it now, but you may be someday."

And I was when I began doing this book.

I kept asking my father about them and found out eventually, in a moment of grief, after her death, my father burned them.

And at that point, I get furious, yell at him, call him a murderer, then vaguely, superficially, reconcile and walk off with the fact of the matter is, I'll never really get her story.

♪♪ -Art had started working on "Maus."

-Beer, everyone?

-Yeah, yeah yeah, yeah.

And he was always saying, "Oh, somebody should print comics and magazines.

Somebody should print comics in The New York Times.

-Trying to figure out lettering that would be on the cover.

-And he was always disappointed when they never followed through.

I decided to do Raw magazine.

In 1982, put together all the ideas that Art was ceaselessly advocating for.

♪♪ The idea was to do something that was of its moment but also would have the permanence of a book.

-The magazine is not just a publication, but it's also where you store weapons.

The idea here was to put things in juxtaposition that could explode.

And by putting these different kinds of artists together, it was really possible to shape something that became a vision.

[ Laughter and applause ] -I'd been waiting since about '72 for something like Raw, 'cause I was in a modern art, and so I thought comics had a place in that.

This character is an amalgamation of a lot of characters, and it's got Nancy, Orphan Annie, Popeye's chin, Dick Tracy's chi-- other chin -- [ Laughs ] -- and ducks.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Indistinct conversations ] -I had met Art and Françoise in maybe 1980, '81, and I realized that they were publishing Gary Panter.

I knew that I was gonna be in good company.

♪♪ -Reading Raw in high school and in college, I was radicalized.

I studied every single issue.

I had them out on my drawing tables in college.

I took them to painting class with me.

I owe my life to Art and Françoise.

They provided an example of an art to me when I was a kid that has really meant the world to me, and they've meant the world to me.

And in a lot of ways, I feel like I'm up here with my mom and dad in sort of a strange way.

-We put our two projects together.

I encouraged them to put the first chapter of "Maus" in the second issue of Raw.

So, when we decided to insert "Maus" into Raw, we ended up having to do a couple of things.

One is create another booklet that would be a totally different size and that would make it rest by itself.

And then Art had to draw a page that the booklet would rest on, and then give a synopsis of the story so far.

So the shift in size was specifically to make you stop and feel like there was a whole other approach to comics and graphics that was done in a more intimate style.

-A chapter appeared in each issue of Raw magazine.

The pictures are totally in service of the story, and so they're very quiet compared to other comic books and compared to other things that I've done.

When I'm drawing "Maus," I end up working on typing paper.

I use a fountain pen and liquid paper to white it out.

I want to feel like I'm writing, so I'm using stationery supplies.

So it would be more like picking up on a journal and looking over one's shoulder to read that journal.

To me, that's part of the intimacy that comics are capable of.

And that intimacy is something that was very necessary for me in the strip.

They're masks that these characters are wearing.

And, of course, my father was a collaborator on the book, but then, so was Hitler, and it involved taking that rhetoric and turning this notion of the subhuman back on itself and letting these mice stand on their hind legs and insist on their humanity.

♪♪ -This, to me, is one of the most important pages in the book.

Vladek Spiegelman and Anja Spiegelman, Art's parents, were in the city of Sosnowiec in Poland.

The Nazis have hung four Jews publicly as punishment for trading on the black market.

And it gives us a very large image that's also an unbordered image.

This page is spectacular, in a sense.

It's kind of unbounded.

It's asking readers to slow down and to encounter a shred of the horror of what Vladek must have felt, because he goes out to look at these people, and these are people that he knew.

And then yet another thing this page does is that it gives us what art has called literal footnotes.

We see these men hanging, and then we get a view in two panels below of just their feet, which would seem to be dehumanizing, but it's exactly the opposite, because in the prose below their feet, we learn details about them as people.

-"They hanged there one full week.

Cohn had a dry goods store.

He was known over all Sosnowiec.

Often he gave me cloth with no coupons.

I traded also with Pfefer, a fine young man -- a Zionist.

He was just married.

His wife ran screaming in the street."

-I think of this page as an example of "Maus's" explicit anti-fascism by particularizing not only survivors but particularizing victims that the Nazis wanted to remain nameless.

-Art has never separated work and life, so, of course, this is what he thought about, what he talked about.

And he got stuck so many times.

And all I could do was, um... you know, be supportive.

-"I know this is insane, but I somehow wish I had been in Auschwitz with my parents so I could really know what they lived through.

I guess it's some kind of guilt about having had an easier life than they did.

Sigh.

I feel so inadequate trying to reconstruct a reality that was worse than my darkest dreams.

And trying to do it as a comic strip!

I guess I bit off more than I can chew.

Maybe I ought to forget the whole thing.

There's so much I'll never be able to understand or visualize.

I mean, reality is too complex for comics.

So much has to be left out or distorted."

"Just keep it honest, honey."

"See what I mean?

In real life, you'd never have let me talk this long without interrupting."

"Hmph.

Light me a cigarette."

-I did see it build upon itself.

And some things were happy accidents, like the publication of the first book as a book, and then the extraordinary feedback that it got early on.

It was the right thing at the right time.

And the despair that that threw him in.

-The success of "Maus" was a setback.

I literally was set back onto a couch staring at a stain for months on end.

Um, eventually, Françoise dragged me to a shrink she had met who was the ideal way out.

He had survived Auschwitz.

We went to the ruins of the barracks my mother had been in and also to the site of the crematoria and gas chambers.

It's an incredibly... dark thing to have to, like, delve into day in, day out.

And there seems to be something insane about achieving some kind of celebrity for -- for, uh, working in that area.

You know, like, there's no way that that, uh, feels deserved or -- or, um... relishable, you know?

Volume one was mostly taking place in the ghetto, and volume two is about the oxymoron of life in a death camp.

I couldn't imagine it.

So I went to Auschwitz.

Two different visits.

This is one of the four crematoria and gas chambers.

People came down those stairs over there, undressed, left their clothes over there, and were taken to a shower, to take a shower over here.

These were the crematoria where they burned the bodies.

Went up in smoke.

♪♪ I began working on the second volume.

♪♪ -I remember being in France in the summer, and we had baby Nadja by then.

And I wanted to take her to the beach and, um... And I was very happy as a mother.

And -- and then, I would walk into the house, and then, here was Art, like, struggling on whatever chapter this was in the second book.

And I was like, "Oh, my God.

When is this ever gonna end?"

Because, you know, the second book is called "And Then My Troubles Began."

Um, so, you know, the descent into hell, just it kept going further down and further down.

I mean, reading about Hungarian Jews arriving in the summer of 1944.

I mean, this is like the end of the war.

Um, they were killing 10,000 people a day.

It just -- it just was...

It was both inconceivable, but it was the task at hand.

-I'm gonna show you these three panels first, okay?

Françoise and I are sitting around the Catskills table with my father.

I'm drinking coffee, and Vladek is saying, "When the Russians came near, the Germans made ready to run from Auschwitz.

They needed tinmen to pull apart the machineries of the gas chambers.

They wanted to pack it all to Germany.

There they could take all of the Jews to finish them in quiet.

The Germans didn't want to leave anywhere a sign of all what they did.

You heard about the gas, but I'm telling not rumors, but only what really I saw.

For this, I was an eyewitness."

You see a progressive close-up of Vladek, and it turns into a close-up of the gas chamber.

There's also, as an aside, smoke coming out of the gas chamber, which turns into the smoke of my cigarette.

But in that sequence, he's telling me what he saw and describing very, as accurately as he can, the gas chamber, and I took whatever information I could get to be able to visualize that.

So it included, uh, diagrams that were in the Auschwitz history guidebook that was on sale at the camp to figure out what it looked like exactly.

And then, he's describing the process of dismantling.

And -- and then he talks about how one of the worst things that he saw was the way the Hungarians were treated.

They were brought in very late in the war, uh... and...says...

He's talking with somebody else working on the tin detail.

"What are they doing over there?

Digging trenches in case the Russians attack?"

"Trenches -- ha!

Those are giant graves they're filling in.

It started in May and went on all summer.

They brought Jews from Hungary -- too many for their ovens.

So they dug those big cremation pits."

And my father says, "The holes were big, so like the swimming pool of the Pines Hotel here.

And train after train of Hungarians came.

And those what finished in the gas chambers before they got pushed into the graves, it was the lucky ones.

The others had to jump in the graves while they still were alive.

Prisoners would work there, poured gasoline over the live ones and the dead ones.

And the fat from the burning bodies they scooped and poured again so everyone could burn better."

"Jesus," I say.

Now, that was hard to visualize, it was hard to even tell, and I was very cautious about how to tell and draw this.

I needed -- The only photograph I could find of anything relating to this, just to begin to imagine, it turns out there was a clandestine photo that was taken in Auschwitz of the burning pits, and it was smuggled out of the camp.

So that photograph I leaned on for some authority.

This picture was one of the hardest for me to draw in the whole book, and I've tried my damnedest, not always successfully, but I tried to not let this picture be printed out of context because it had to be horrible.

♪♪ At some point, I had 20, 30, 40 sketches of how to draw this thing.

And the one clue for me was, usually, almost always the mice are shown with their nose at the bottom of the head and seen that way, and by lifting the head up and seeing their mouths shrieking, they became human.

-There wasn't a sense of like, "Oh, my God.

He's making a masterpiece."

I didn't perceive of it that way because, I mean, when I met Art, he was a master and nobody else knew it.

That was the basis of my -- my love and then my life, um, that, "My God, this guy is amazing!

And isn't it incredible that the world is not paying any attention?"

-[ Speaking Polish ] You know, I like the idea of being able to spit in somebody's face and being able to, like, say, "See?

Here we are."

And, uh, we've got a baby, and life goes on in spite of everything those bastards did.

That's something, you know?

Like, to be able to go there and walk away from it, that's something.

♪♪ This is the family tree of Vladek's side of the family, one branch before the war and after.

♪♪ -I think that there's a lot of difficult to express emotions that I feel when I see this blank page.

I've always grown up with that feeling of, we are on a little ship with the four of us in my nuclear family in this kind of existential sea.

-There's an inherited sense of loss, of the enormous family that was lost.

There was a bookshelf that contained every book about the Holocaust that my dad had been able to find at the time that he was working on "Maus," and I was very much given the impression growing up that he had absorbed my mother, also, in helping him with the research process, had absorbed these incredibly intense horrors in a way that was sort of like, "We did it so you don't have to."

-This comic that I'm about to read for you guys by my dad, Art Spiegelman, and it's "A Father's Guiding Hand."

"Hey, Dash, look at what Papa has for you."

"A present!"

"Yep!

It's been in the family for years.

My dad gave it to me when I was a little boy."

"It's old, huh?"

"And now I'm giving it to you."

"What is it?

A monster?"

"It's magical!"

"It -- It's getting bigger!"

"It makes you feel so worthless, you don't believe you even have the right to breathe!"

"Aah!"

"And just think -- someday you'll be able to pass it on to your son!"

"Thanks, Papa."

♪♪ -The 1992 Pulitzer Prizes were announced today.

Among the winners, a special Pulitzer was awarded to Art Spiegelman for a cartoon book depiction of the Nazi Holocaust called "Maus" -- M-A-U-S. -Other renowned cartoonists are delighted the Pulitzer board has recognized just what can be accomplished in their field of work.

-I think it says something more for the Pulitzer than it says about my field.

I mean, all honor is due to the Pulitzer to recognize this kind of brilliance.

It doesn't come around often.

-Art Spiegelman's parents survived the war... -The thing that amazed me about "Maus" was the audacity to come up with this and to be able to make this work.

It was -- It was astonishing.

-What about some people who may be offended?

I read two remarks.

One of them was that "The cartoon mouse image either trivializes the Holocaust or, at some level, reinforces the rodent image appropriated by the anti-Semites of the era."

How do you answer them?

-Well, read the book, I think is the easiest answer.

♪♪ I enjoyed reading the reviews of "Maus" in different countries because the emphases would change.

In America, there would usually be a paragraph saying, "Well, I don't know.

Is it comics?

Is it a tragics?"

In Germany, there was much more concern about the propriety of using comics.

At one point, I remember being interviewed and asked, "Do you think it's in bad taste to have done a comic book about the Holocaust?"

I said, "No, I think the Holocaust was in bad taste."

♪♪ I've had to come to terms with, "Okay.

If I have a posterity, it's through that work," and I am now proud of what I did.

But I had no expectations when I was making it that it would be discovered while I was alive.

I really thought we would be publishing it ourselves, and it would be discovered more or less posthumously.

It did leave me feeling drained, "Maus."

-When The New York Times put it on the fiction side of the bestseller list, Art wrote this amazing letter to the New York Times Book Review.

They published Art's letter, in which he says, you know, "If I had a novelist's license working on this book, I could have lopped some years off of the 13 that I spent researching it."

So here's a book that was moved to nonfiction that portrays humans as animals.

And in that moment, these huge, dominant cultural institutions like the Times had to debate, "What does it mean to take drawing seriously?"

♪♪ That was a major cultural shift that basically allows us to have the field of comics that we have today.

♪♪ ♪♪ -I did a book after "Maus" called "The Wild Party," which was a very obscure narrative poem.

It had a kind of great, scurrilous quality, and it was meant to be erotic.

♪♪ The whole thing was to be able to enjoy giving life to his words.

♪♪ [ Gunshot ] It was a move sideways, as was joining up with The New Yorker.

♪♪ -Once Françoise started working at The New Yorker, that was kind of the next big platform for both of them.

♪♪ -When I got invited to work for The New Yorker, I got in a lot of trouble there.

Like, there were scandals based on the covers I was doing.

About the time I was invited in, it was Valentine's Day that was coming up, and I was thinking about the Crown Heights riots that brought the West Indian African-American community and Hasidic Jews to blows.

I was just doodling, and I was drawing that Eustace Tilley guy with the monocle and said, "I wonder what he'd look like if he was a Jew, so I just put a Hasidic hat and beard on him, and then before I knew it, he was kissing this West Indian, African-American woman.

And that was my Valentine's cover, you know?

Why don't they just kiss and make up?

Man, did that get people upset.

That was the one that really did it.

[ Laughter ] ♪♪ -He's very good at comics, which are sequential images, but he's also really good at the one image.

It's like poetry and prose, they're different things, but the single image can be used to elicit an emotion or a thought, and it can also be used to really upset people.

And sometimes those are the same things.

-One of the issues that was happening around that time was the Amadou Diallo case, an African immigrant who was coming home from work into the Bronx who was surrounded by cops, told him to freeze, then asked for his I.D.

When he reached for his I.D., they assumed he was reaching for a gun, and they just opened fire, en masse.

My idea was to have a cop that looked like the friendly, apple-cheeked Casey the Cop, happily and affably shooting at the silhouetted targets, where it says, "41 shots, 10 cents."

And one of the smartest things about this cover, if I say so myself, is that the targets are all black.

But because they're silhouettes, it doesn't read as Black Americans versus White Americans.

It just reads as Americans are under fire from their police.

-New York is talking this week about the image one magazine put on its cover.

-A complicated message about cops and police brutality, depicted with an edge sharp as razor wire.

-I think it's irresponsible.

It's outrageous.

-Police Commissioner Howard Safir is furious about the latest cover of The New Yorker magazine.

But whether you love it or you hate it, one thing is clear -- this cover art has struck a nerve.

♪♪ -This fall will be the 10th anniversary of the publication of "Maus," which I consider a true American masterpiece.

What "Maus" is, is it's what I guess maybe Truman Capote would call a nonfiction novel.

Do you believe that, uh... that you have another -- another story that's extraordinary in you?

I mean, I know that's a rough question.

-I don't know.

I mean, you know, this was such a extended birth pang, getting this thing to happen -- like you said, 13 years, you know?

I'm at the early stages of just poking around for something that's worth contracting this long-term disease, like going in for a book and coming out 7 or 8 or 9 years later.

So I've been doing a lot shorter hits, one after the other, in the hopes that one of them will flower.

-Achieving something of a super high level when you're really young, it's like giving yourself a father to outlive.

And so it's doing that, and he's tortured by that.

"I was just another baby boom boy.

I grew up in Queens, I loved comics, my parents survived Auschwitz.

It's all a matter of record.

I made a comic book about it.

You know, the one with Jewish mice and Nazi cats.

Mein Kampf (My Struggle).

I still prowl the murky caverns of my memory.

But now I feel like there's a 5,000-pound mouse breathing down my neck.

Remembering those who remembered the death camps is a hard act to follow."

♪♪ But just show the other one and put this one as a group of rows.

Color, black-and-white, color, so we'll swap these two.

And now they're actually -- presto -- in chronological order of when they were made.

So, what do you think?

I think that maybe that could still be there.

-Does it fit?

-It could if we have a certain aesthetic to it, right?

Like, I mean, these are rare, but I have that.

That's the actual cover of The New Yorker?

-Yeah.

-And, like, you could really go for a long time without knowing that there's anything on there.

It depends on how the light hits it.

And all of a sudden, the ghost of the towers comes in.

♪♪ My high school was right underneath the World Trade Center, and it was my second or third day of high school when 9/11 happened.

And it was a very difficult day, which my dad then wrote about in this book.

The school was shaking, the lights were going on and off, teachers were running out of classrooms.

Some kids were glued to the windows, watching people jump.

And my parents came to get me.

-We went dashing down there.

We got her out and began walking to the West Side Highway.

We turned to see the towers.

At that point, the other tower was on fire, as well, and what we saw was so astonishingly unreal-looking.

-My dad and I and my mom, as well, witnessed something that you never see in the footage of 9/11.

It looked like all of the gray of the tower fell first, and then there were these bright-red beams that hung in the air for a really long time, and then those bright-red beams slowly disintegrated.

And I remember seeing that so vividly.

And the fact that my dad saw it, too, and then drew it is really beautiful.

"Equally terrorized by Al Qaeda and by his own government, our hero looks over some ancient comics pages instead of working.

He dozes off and relives his ringside seat to that day's disaster yet again, trying to figure out what he actually saw.

What I did find myself doing almost immediately was hide out in what I understood, which was the old comics that...nurtured me.

And so I was just looking at the old Sunday tear sheets that I had, and those just gave me a feeling that civilization was worth saving.

The conceit that occurred almost as soon as I started working on it was that in the shadow of the towers was the Hearst building and the Pulitzer building, the newspaper buildings that published the first Sunday comics in America.

So my notion is, when the towers fell, it disinterred the bones of the comics characters that lay beneath the city.

♪♪ Art always seems to be standing at this point in these histories.

It's hard to remember the atmosphere that was going on after 9/11.

-Anything even mildly critical of the government was seen as almost siding with the terrorists.

Saying that the war fever that quickly ensued was as big a threat as anything that bin Laden had come up with was also not sayable.

I couldn't get anybody interested in publishing it.

And then, when it did come out in Europe, I just felt like I was an ambassador to prove that America wasn't as crazy as Europeans thought we were.

Because my attitudes were almost mainstream there.

I was amazed because the forward came through and actually, without worrying about my politics or theirs, I got the back page whenever I wanted.

-We published an issue of "World War 3" within months of 9/11.

Here's the issue.

This is the pre -- right before we went into Iraq and Afghanistan, where we said, you know, "Hey, let's not do that.

This is a terrible idea."

And there's Art on the inside cover.

-In the introduction to "In the Shadow of No Towers," he talks about this idea that "disaster is my muse."

-It's true that Art has a degree of comfort with misery.

One thing that he heard from his parents, clearly, is it can all be taken away from you from one day to the next.

So he expects the sky to keep falling, and sometimes it does.

-His father wanted to teach him to keep his bags packed in case the world grid crumbled, which was, you know, precisely a lesson that Vladek had learned from World War II that seemed to be happening during 9/11 for Art.

-25 years ago, Art Spiegelman published "Maus."

Now he's published "MetaMaus," a book and DVD about the making of "Maus."

You produced "MetaMaus," partly, I think, because you thought it was time to draw a line underneath the whole episode 25 years on.

Yet here we are, still talking about it.

Is this something you can ever put behind you?

-I like to think so.

-I know you wrote "MetaMaus" so that people would no longer ask, "Why pigs?

Why mice?"

But I'm going to ask the question, why mice?

♪♪ -"The book seems to loom over me like my father once did.

Journalists and students still want answers to the same few questions.

Why comics?

Why mice?

Why the Holocaust?

Yikes!

Or to quote my forefathers, oy!

But I thought I'd finally try to answer as fully as I could.

That way, when asked in the future, maybe I could just say, "Never again."

And maybe I could even get my damned mouse mask off.

I can't breathe in this thing.

Oof!

Urk!

Unff!

Grunt.

Ahh."

"MetaMaus" is a book about the making of "Maus."

Art and I just talked to each other for two years, and then I edited the transcripts.

The book has three threads.

It's about the aesthetic research that went into "Maus," the historical research that went into "Maus," and the family research that went into "Maus."

♪♪ ♪♪ I think he had a sense, when he was doing "Maus," that he was going to do it, and he was gonna bury these memories in panels.

-In the very last page of the book, after you see Vladek and his birth and death date, and next to him, Anja's birth and death date, just as it looks on their tombstone.

Below that is the signature of when I started "Maus" and the death date of the book when I finished it.

-He had to think about all this stuff again for "MetaMaus."

He recognized how useful "Maus" was as a text for people explicitly reacting to and fighting fascism.

-My name's Art Spiegelman.

[ Cheers and applause ] Thank you.

Thanks.

I'm going to read a poem by Frank Zappa.

[ Cheers and applause ] Hopefully next year's posthumous winner of the Nobel Prize for literature.

From the 1966 Mothers of Invention album, "Freak Out!"

-Yeah.

"It Can't Happen Here."

So I apologize for not being able to read properly off-key.

"It can't happen here.

It can't happen here.

I'm telling you, my dear, that it can't happen here.

'Cause I've been checking it out, baby.

I checked it out a couple of times, hmm?

And I'm telling you, it can't happen here.

Oh, darling, it's important that you believe me.

Bop bop bop bop.

That it can't happen here."

-A Tennessee school board has banned the critically acclaimed graphic novel "Maus."

-I was flabbergasted and then angry and then flabbergasted again.

-A 10-0 vote removed the novel about the Holocaust from the classroom, citing profanity, nudity, and scenes deemed too inappropriate for children.

-Here you are now on a news show after a year of pretty constant interviews, having to discuss the banning of "Maus" or people who don't want people to read it.

Let's talk more about that, that you are now the story about the story.

-Yeah, and I've made a -- I've taken great pains to expand it from "Maus" to talk about all the other book banning that's going on, 'cause I've been kind of puzzled by the focus on "Maus."

-Joining me now is Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer Prize-winning artist, illustrator, and author, and Jerry Craft, Newbery Medal-winning illustrator and author of "New Kid," a graphic novel pulled by a Texas school district after a White parent complained that it promoted critical race theory and Marxism.

-It's a Black kid going to private school.

There's no cursing, there's no sex, there's no drugs.

"New Kid's" in like 13 different languages.

So you could read it in Spanish, French, Korean, Romanian, German, Albanian.

You just can't read it in parts of Texas or Florida.

-I never thought I would live to see something where America, which saved my parents after the war -- it gave them a new start in life -- could be tilted toward a new kind of fascism.

And that's what I see everywhere I look now.

But you know the images of Nazis burning books in the '30s in Germany.

And now books are being thoroughly banned in libraries in Missouri, in Florida and Texas and in Tennessee.

It's like destroying memory yet again.

It's that when I called my father a murderer for murdering the written word, the diary, it's what we're doing to our entire culture by murdering the books, banning them, taking them off shelves.

♪♪ I think we're in for a fascist society unless things change around 180 degrees.

This is really dangerous times.

I never thought I'd see anything like this again.

It won't take exactly the same form, but it's clear that, as Faulkner said, the past is not dead.

It's not even past.

And...that informs all of this thinking.

This is an image I made called "The Past Hangs Over the Future."

Me with my daughter mouse, Nadja, when she was very young and hanged Jews hanging behind it.

[ Applause ] Nothing like a lifetime achievement award to make me feel like my lifetime might be over.

[ Laughter ] My year culminating in this award has been really sobering.

I'd always vowed to not become the Elie Wiesel of comic books.

[ Laughter ] In fact, in the years after "Maus," I would draw myself trying to outrun a 500-pound mouse, trying to either evade or supersede that work.

But now I've had to try to become a mensch.

It's been a long march to turn around and embrace the 500-pound mouse, while fascist storm clouds gather yet again all over our frying planet.

So I'm even grateful that "Maus" may now have an afterlife as a cautionary tale, that it might make readers insist, "Never again," in the future, even if the past for other minorities has often been a matter of never again and again and again.

♪♪ ♪♪ After being a poster boy for books being censored, what I was calling the Tennessee Waltz while it was going on, I eventually stopped drawing altogether, and as a result, my hand froze.

It's not like a bicycle.

You don't just get on and remember how to stay balanced.

When I was a kid, one of the things that first made me kind of enjoy making marks on paper was a kind of a game my mother would play with me.

She'd make a bunch of scribbles and say, "What does that look like?

Draw it."

And so I'd look around and then just draw something, and then I'd do a scribble for her.

And I mean, she kind of cheated.

She would just make more scribbles and make it into a hairdo.

And then she could draw a profile of a woman's face that she knew how to draw.

So it was always just different hairdos on that head.

Recently, I was messing around with watercolor.

I'd just make a bunch of scribbles, but in color, or at least in gray for many of them.

And then I'd let it dry, and then it was like looking at clouds and I'd just start making something.

So it helped me overcome my recent inhibition about drawing anything at all, because it was always getting me into trouble, this drawing stuff.

So this was one of the first ones.

This one was, "Meanwhile, in a universe next door, the Earth is destroyed by a giant-sized chicken."

I didn't understand it right away, but part of it really was getting in touch with my mother again.

Getting in touch with my mother and father was part of reliving "Maus" for that year and a half of having to talk about it in public from a different angle than I ever had to before.

So I'm doing these weird drawings, and I figured, "Okay.

I'll just make a bunch of shapes, but afterwards, I'm going to look for a mouse head."

And I began to just draw around it, and it grew into a picture.

And it's a mouse suspiciously looking like the one that represents me in the book with a vest.

And there's a Ku Klux Klansman holding a very large wild cat.

And the cat, which is, of course, a symbol for fascism in "Maus," is scratching my face.

It was an image of book burning and banning with a pig breathing flames, small cat in the background with a Hitler mustache somewhere.

And it's just finding what could happen around this image of the cat scratching.