The first time Marcella Hazan cooked a full Italian meal, she did it in Forest Hills, Queens.

Hazan moved to New York with Victor, her Italian-born American husband, in 1955. She knew no English, but she taught herself the language by watching TV—especially Brooklyn Dodgers games—in their Queens apartment. It’s also where she taught herself to cook. “I never cooked a day in my life until I was married,” Hazan said. “I never boiled water if it wasn’t in a beaker in the laboratories.” That made no difference: when she started cooking, it came to her as easily “as words come to a child, when it is time for her to speak.”

***

“The cooking of Italy is really the cooking of its regions”

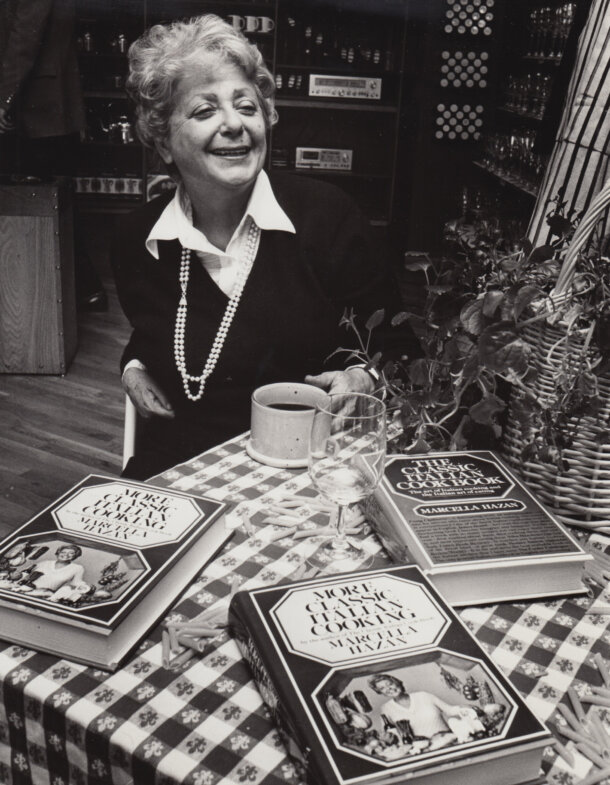

Hazan published “The Classic Italian Cook Book” in 1973 with the help of her husband’s translation. In its introduction, she wrote: “The cooking of Italy is really the cooking of its regions. Regions that until 1861 were separate, independent, and usually hostile states. What is important is to be aware that these differences exist, and that behind the screen of the too-familiar term ‘Italian cooking’ lies, concealed, waiting to be discovered, a multitude of riches.”

Hazan is from the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, part of what is perhaps its culinary heart. Her first book focused mainly on the Northern Italian dishes she grew up with.

When Hazan arrived in the United States, the American conception of Italian food was informed by immigrants who came almost exclusively from Southern Italy. The existing Italian American cuisine was a bastardization of Southern cooking: it was unfamiliar (and wholly unappealing) to Hazan. It was her influence that transformed the American understanding of what Italian food could be: recipes that rely on the strength of a select few ingredients and the skill of combining them intentionally.

Her extremely popular tomato sauce is just tomatoes, butter, a halved onion (removed before serving) and a pinch of salt. In her son Giuliano’s words, being from Emilia-Romagna meant Hazan liked to use butter—in her first book, the tomato sauce calls for half a cup of butter; it is edited down to 5 tablespoons in the later volume “Essentials of Italian Cooking.”

Another one of her most well-known recipes, roast chicken with lemon, is a whole chicken, seasoned with salt and pepper, that harbors two perforated lemons inside its cavity. In the recipe’s preamble, Hazan wrote: “Were I to choose a dish to show how the simplest cooking can also be the most sublime, I would take this one.”

When the recipe ran in a women’s magazine, the publication received several letters from readers who claimed their boyfriends were so impressed with the dish, they proposed shortly thereafter. It earned a new title: Engagement Chicken. Despite its promise for romance, Victor, whose palate Hazan catered to the most, had no interest in chicken.

Her bolognese—which has its roots in Bologna, where Hazan taught cooking classes for many years—is a lesson in Italian cooking as architecture. The seven ingredients are layered together at the proper time and temperature and then left to simmer for three to five hours. Hazan knew when each stage of the dish’s construction was complete not by how it tasted, but by how it smelled.

Risotto, another staple of Northern Italian cooking, was the first thing she taught Giuliano to make. As a kid, Giuliano would sit in the kitchen and watch his mother cook. Sometimes, she would let him help—and one of the tasks she delegated was stirring the risotto. Hazan was loyal to Carnaroli risotto (dubbed the “king of rice”) grown in the Po River Valley. Her recipe for risotto with fresh tomatoes and basil produces grains that have absorbed both the flavor and color of peeled plum tomatoes.

While her most famous dishes adhere to the culinary traditions of the North, her second book approached Italian cooking more holistically. The Hazans traveled around Italy, eating at restaurants and in homes and capturing conversations on a tape recorder. She would spend a month or so in each place, trying to get a feel for the people and the food. The dishes she liked, she recreated and refined into original recipes. Giuliano recalls the month his parents rented an apartment in Sori, a coastal town in Liguria just south of Genoa. Hazan’s recipe for focaccia with fresh rosemary, which originated in the area, remains a staple in “Essentials of Italian Cooking.”

Hazan spent the last fifteen years of her life in Longboat Key, Florida, near where her son settled. In comparison to the previous 20 years in Venice—where the nearby Rialto Market boasted broccoli rabe, rucola, and fish so fresh it was odorless—Longboat Key was a food desert.

She began creating recipes that used ingredients more accessible to American audiences, and she ordered what she could find online. When her name popped up on an order list for Rancho Gordo Beans, an American-grown heirloom beans company, its founder was stunned. The two began messaging on Facebook, and at Hazan’s request, the company started producing the Tuscan sorana cannellini beans she had been missing. They’re still sold today as Marcella beans.

***

In the volumes of recipes Hazan leaves behind, she is notably precise for a chef who never measured and notably warm for a woman known for her stubbornness. After her death, Victor told The New York Times: “Marcella wasn’t easy, but she was true. She made no compromises with herself with her work or with her people.”

Victor championed that uncompromising truth in every last one of the recipes they published together—in New York, Venice and everywhere in between.