Here is the minaret, outlined against burning blue sky, here is the carpet, thin and brown and frictive against the feet, here is my small face half-reflected in the balcony window, superimposed against Muscat, white city bookended by low mountains and gem-blue sea. In the memory, I touch the glass, press my face to it.

What does it mean to have a home, lose it, and realize in adulthood how tenuous and conditional that home was in the first place? Whose work, whose labor, makes a home a home? These questions, and others, have animated my current novelistic project “In The Desert.” In his short film “After All This,” director Andrew Nadkarni honored my work through his deft, tender, searching portrayal of me laboring to write this book, and I will always be grateful to him, Maryam Mir, and the larger team behind the film for that.

The question of home loomed large in my first novel, “All This Could Be Different,” too. The novel’s protagonist, Sneha, is living an unstable life, trying to make her way by herself in the harsh and intoxicating country that is the U.S. during the early 2010s. Her immediate family has been forced to leave, return to their village in South India; Sneha works as a consultant in the American Midwest. “All This Could Be Different” explores the notion of the imaginative, reparative home. Sneha’s best friend imagines home not through the lens of individual property ownership, but as a collective that can, in part, save and protect both of them as well as their struggling and precarious friends. Sneha, much less of a political radical, more of an everyman, is both compelled and wary, filled with longing and mistrust at once. You watch her, though, over the novel’s course, change as a person. She unfurls, she softens, she learns, you could say, amidst the great migrational uncertainty of her life, to find a home in other people.

Writers and artists through time have grappled and sparred with the notion of home, and none more so than the exilic artist, the artist who has lost or forever left the home of origin.

Jamaica Kincaid writes with ambivalent, sometimes derisive, longing for the island life of her youth; Mavis Gallant makes the space of dislocation and expatriation its own country and renders it as rich and vivid as any nation; Marguerite Duras conjures her-long lost world like a shocking spell. Ayad Akhtar skewers the ideas and propagandas of his home country and then breaks our hearts with it. James Baldwin insists on the right to love and thus to criticize his home, his radiant and heartbreaking and contradictory country, the United States of America.

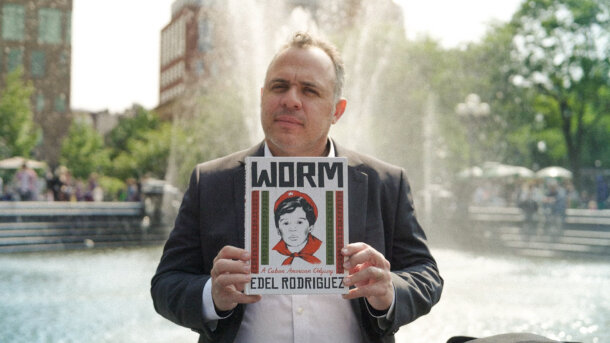

Many of the artists profiled in the most recent season of In The Making grapple similarly with the notion of home in their work. In “Estranged Letters,” we see Maryam Taghavi procedurally slowing down and making visual her mother language of Farsi in her art practice, stripping down its parts into a haunting minimalism. In “Freedom Is A Verb,” Edel Rodriguez honors his past exilic home and his present one, in part through critiquing it in the Baldwinian tradition.

Baldwin famously said, “I consider that I have many responsibilities, but none greater than this: to last, as Hemingway says, and get my work done.” and then added, “I want to be an honest man and a good writer.”

Like Jimmy Baldwin, I wish to pursue the project of honesty. We are living through a time of rupture and profound crisis. Publicly funded media, including PBS, which is how any of these films came to be made at all, is under attack. My friends and neighbors are under attack—genuine, life-threatening, material attack. The question of home, then, is inseparable from the question of who is permitted to belong in our nation’s present form. Much of the work of artists and writers who are aligned with a vision of America as a pluralistic and multiracial democracy–including many of the artists profiled in In The Making–is being maligned or dismissed as made irrelevant by the “vibe shift” of the 2024 election result.

In sum, my new home country, the home of my adult life, is changing and mutating rapidly. There are many reasons for these changes. One of them is what I think of as a reactionary spirit, a kind of poisoned mourning for an imaginary past where everything was traditional and blessedly simple, where might made right. One is this country’s essential contradictions turned inward and violent. But another, complex reason, is what I think of as the representational trap, the idea that any of our stories really only have import to people like us along the axis of identity–that the art that a woman makes only really speaks to other women, an Asian person to another Asian person, white men to white men, and so on. Part of the mechanism of the representational trap is: someone sees a work made by someone different from them and instinctively thinks, “What does this have to do with me?”

As I’ve worked on my novel over the months and years, I have thought a great deal about migration, the profound and altering experience of it, the complication inherent within translating it to those who’ve lived it as well as those who—thus far—have not known its ways. For me, writing about the experience of migration is not only representational work, or an attempt to speak to other immigrants, by any means. It is also, for me, an attempt to say something to all those who face real rupture, which is now, nearly everyone.

Art, in my opinion, has everything to do with recognizing oneself in the other.

In that moment of recognition, there’s the beginning of a foundation laid for an ethical imperative: if we are different but also alike, perhaps our futures are bound up together, perhaps we must do each other the labor and service of understanding each other’s worlds and histories, perhaps we need each other–in wild and terrifying and exhilarating ways. A country that shuts down these ideas cannot be a democratic one, a pluralistic one, a free one. In considering a current government regime that curtails our rights and our freedoms, it’s useful, to me, to consider how important it is to uplift and protect art and media built around the impulse to recognize.

To recognize what is universal to all of us, to deepen that in the specificity of any single person’s story, including but not limited to the profoundly human longing for home, for what we have lost and are in the process of losing, for what is good and beautiful and enduring in our shared world.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.