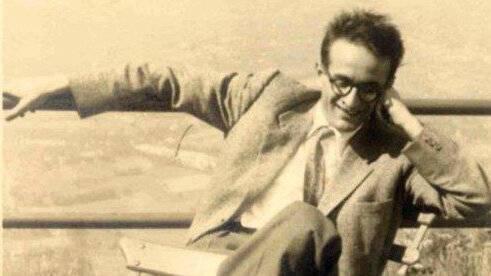

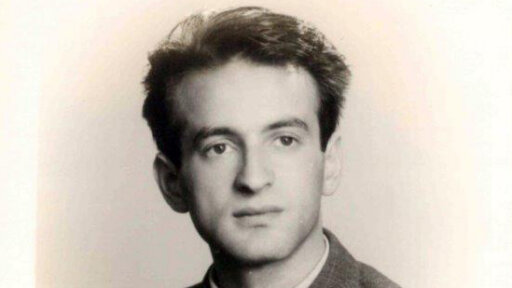

Elie Wiesel (1928–2016) was one of the most influential writers to emerge from the Holocaust, drawing deeply on his own experiences in two Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Shaped by both the physical suffering he endured and the devastating loss of family members, Wiesel became a writer, professor, and activist whose voice resonated across the world.

Reflecting on his calling, Wiesel once explained, “I write to bear witness.” Through his work, he transformed personal tragedy into a universal call for remembrance and moral responsibility.

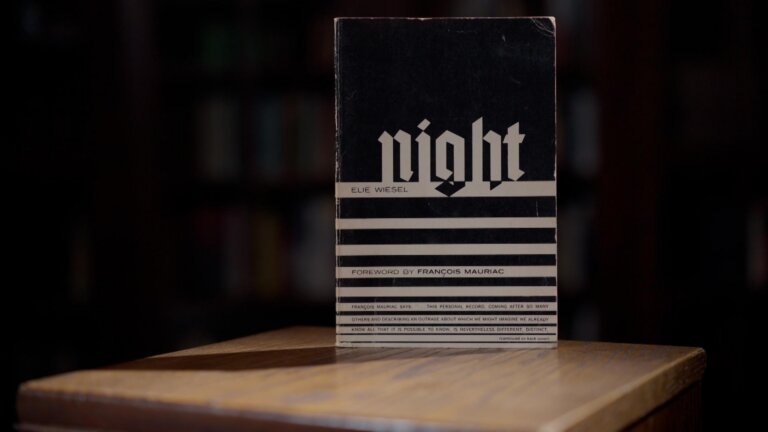

Over the course of his career, Wiesel published more than 40 works of fiction and nonfiction, beginning with “Night,” the haunting memoir that told his personal story. While “Night” remains Wiesel’s most well-known work, many of his other writings are equally deserving of close attention. Here are five of his most defining works.

1. The “Night” Trilogy: “Night” (1958), “Dawn” (1960), and “Day” (1961)

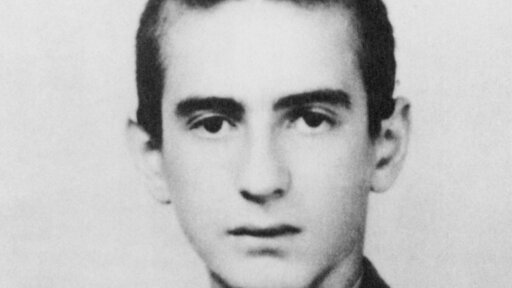

In the spring of 1944, 15-year-old Elie Wiesel and his family were deported from their home in Romania to the Auschwitz concentration camp. His mother and younger sister were killed soon after their arrival, while he and his father were forced into hard labor before being transferred to Buchenwald. There, his father died of an illness just months before the camp was liberated on April 11, 1945.

The loss of his family and the trauma of the Holocaust left a lasting mark on Wiesel, shaping his life and work. It would be ten years before he was able to write about his experiences, eventually producing the three works that make up what is often called The “Night” Trilogy: “Night,” “Dawn,” and “Day.”

“Night” is regarded as a masterpiece of Holocaust literature. Written in first-person, Wiesel recounts his time in the camps, his bond with his father, and his tormented questions of faith amid human cruelty. “Dawn” is a short novel about a young Holocaust survivor who joins a Jewish underground movement in Palestine and is ordered to execute a captured British officer, forcing him to grapple with the morality of violence and retribution. In “Day,” Wiesel turns to the struggles of survivors living with memory, asking whether true freedom is possible for those haunted by the past.

Together, the trilogy charts Wiesel’s journey from the horrors of the Holocaust to the challenges of life after, marking a passage from darkness to light.

2. “The Jews of Silence” (1966)

In the fall of 1965, Wiesel took a life-changing trip to the Soviet Union to write about the experiences of Soviet Jews in the post-Stalin era for an Israeli newspaper. Focusing on communities in large cities such as Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev, he found people who lived in fear of openly practicing their faith, yet who still strongly identified as Jews. In Moscow, one group in particular stood out because they gathered publicly to celebrate Simchat Torah, bravely affirming their identity in defiance of the state’s restrictions.

Living under constant persecution, most Soviet Jews were too afraid to speak openly about their suffering. When Wiesel arrived, they recognized in him a storyteller who could give voice to their experience. The result was “The Jews of Silence,” a passionate plea to Jews around the world to break their silence, support their Jewish brothers and sisters in faith, and advocate on their behalf. The book was a powerful call to action that drew international attention to the plight of Soviet Jews and helped spark activism in the West.

3. “A Beggar in Jerusalem” (1968)

Set in the days following the Six-Day War, “A Beggar in Jerusalem” is narrated by David, a Holocaust survivor and soldier burdened by the death of his friend, Katriel. Returning to the newly reunited city, he encounters those who gather daily at the Western Wall, where the weight of history, faith, and his memory all meet. Through these encounters, David confronts the pain of his past and reflects on the Old City’s enduring significance to the Jewish people in the shadow of both the Holocaust and recent conflict.

The novel shifts between past and present, blending memory, history, and faith, but always returning to Jerusalem. At its core, “A Beggar in Jerusalem” reflects the deep hope of the Jewish people to return to their homeland and live in peace.

4. “Souls on Fire: Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters” (1972)

Wiesel was a longtime scholar of Hasidism, influenced in part by his maternal grandfather, Reb Dodye Feig, a devoted follower of the spiritual movement. In “Souls on Fire,” Wiesel presents a collection of lectures exploring the lives of the early Hasidic masters of Eastern Europe, beginning with Baal Shem Tov, the movement’s founder. He also reflects on the storytelling rabbis and kabbalists who carried the tradition forward.

“Souls on Fire” is not a straightforward chronological history of Hasidism. Instead, it conveys the spirit of the movement through tales, parables, and Wiesel’s own reflections, enriched by his deep knowledge of the Bible, the Talmud, the Kabbalah, and family stories passed down through generations. Though he wrestled with faith after the Holocaust, Wiesel’s study of Hasidism offered a way to rediscover meaning and connect with his spiritual roots.

5. “The Trial of God” (1979)

An accomplished writer across many genres, Wiesel also turned to drama with “The Trial of God.” Like much of his work, it was inspired by his memories of Auschwitz, though the play itself unfolds in a Ukrainian village in 1649, where a pogrom has devastated the Jewish community. As the title suggests, the work imagines a trial in which God is placed on the stand as the defendant.

Wiesel initially attempted to write the story as a novel but felt it was better suited to the stage. He ultimately shaped it into a play to be performed around Purim, presenting it as a “tragic farce.” Through this work, Wiesel wrestles with timeless questions about faith, justice, and divine presence, asking most poignantly where God can be found in the face of human suffering, as witnessed in the Holocaust.

***

From “Night,” written just a decade after his liberation from Buchenwald, to works such as “The Jews of Silence” and “The Trial of God,” Elie Wiesel’s voice endures as one of the most vital in preserving the memory of the Holocaust. Through his writing, he sought to bear witness, to give voice to the silenced, and to remind future generations of the consequences of indifference. His legacy reminds us to remember what happened and to ensure it never happens again.