Writer Clover Hope reflects on how artists featured in In The Making Season 3 are using design, photography, mixed media and fashion to reclaim overlooked histories and reimagine the future through personal and cultural storytelling.

Norman Teague rarely knows what type of furniture he’s building until he begins.

His process is intuitive, sparked by whatever materials he has at hand. The Chicago-based designer has shaped a wheel-like bookcase from bent plywood and a curved lounge chair from rolled steel. His Sinmi stool—named for the Yoruba word meaning “to relax”—is a rocking horse made from bentwood, a seat that invites both play and stillness. For his 2024 exhibit, A Love Supreme, he used John Coltrane’s seminal jazz suite as an emotional framework, reimagining a home by modernist pioneer Mies van der Rohe through a Black lens. Teague brought together more than 35 Black artists for the show, filling it with oblong, functional forms practically begging to be dissected and understood.

Black artists work by exposing the absences—identifying the stories that design history has missed. Teague sees his projects as opportunities to correct a field shaped by a predominantly white gaze. In subverting van der Rohe’s classic minimalist eye, he adheres to Black artistic tradition where form evolves organically. Spontaneity in his work then becomes a form of critique in contrast to the rigidity of Eurocentric designs.

Every artist featured in these four short films from Season 3 of In the Making shares this impulse: to archive and remix stories about Black liberation across disciplines. They tell these stories through furniture (Norman Teague: Love Reigns Supreme), photography (Gioncarlo Valentine: Exposures), mixed media (Danielle Scott: Ancestral Call) and fashion (House of Aama: Threads of Legacy), treating history less as a static timeline and more a constantly expanding record, revised through personal and collective memory.

Excavation is part of the practice. Danielle Scott, a Jersey City-born mixed-media artist, creates portraits, oil paintings and assemblages from found objects.

She sees herself as a vessel for the voices of formerly enslaved Black people who never got to share their stories. “I’m an artist, but I’m also loving that I’m becoming a historian,” she says. For her visual series, Ancestral Call, she used materials like fabric, paper and stained wood frames to recreate portraits of families, incorporating names and genealogies as artistic elements. By adding factual details, figures and color to their narratives, she brings out her subjects’ humanity and gives them permanence.

Her work draws partly from personal lineage—like the rose-embellished portrait of her Polish-Jewish grandmother, disowned for loving an Afro-Cuban man. A trip to Cuba helped Scott further lean into creative risk. A later visit to a Mississippi plantation, where she picked cotton by hand, led to a long-running exploration of her ancestry. The experience inspired her to create nine-foot-long cotton-picking bags to symbolize the enslaved children forced to pick their weight in cotton as young as age six. The discomfort she evokes in her art is intentional; her investigations into her subjects’ backgrounds keep it from feeling like spectacle.

Images can be enhanced or, in other cases, distorted. After Freddie Gray’s murder in 2015, Baltimore-based queer photographer Gioncarlo Valentine noticed how mainstream news depicted Black life with detachment.

In response, he started photographing his community: friends, family, strangers, himself. In one of his photo series, he challenges the stigma around facial tattoos. In another, he photographed inmates at Dillwyn and Buckingham Correctional Centers in Virginia, pushing back against the idea that Black men have to be perfect to be worthy. His portraits have a quiet interiority meant to counter the flood of media images that flatten Black masculinity. His subjects appear to instead look inward through the camera, reflecting a softness often tucked away. He calls his process “breathing with the camera,” allowing his subjects to lead with intimacy instead of masculine performance.

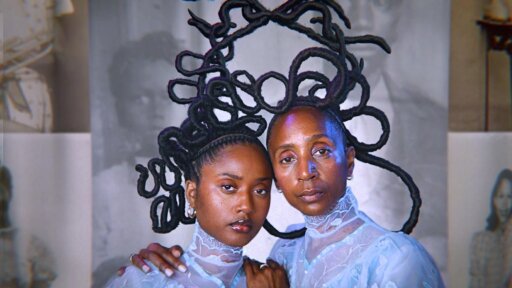

Of course, gaps in history aren’t just absences but results of systemic exclusion, which changes the stakes of these artists’ work from decorative to reparative. Rebecca Henry and Akua Shabaka, the mother-daughter team behind House of Aama, honor their source material by actively embedding it into their clothing.

Their designs reflect their West African, Southern American and Cuban Jamaican roots. In Threads of Legacy, Henry recalls her mother’s tradition of sewing handmade summer dresses; Akua discovered her own love of homespun fashions as a teenager, upcycling vintage finds.

Henry looks at fashion “as a way to tell mythological and archival stories of the Black experience,” she says. Their approach as a design duo is almost archaeological. They’re constantly digging into their lineage and stitching that history into their garments with intricate embroidery, beading and appliqué. House of Aama’s fall 2023 line centered on Anansi the Spider, the beloved folk hero who journeyed with enslaved African families across the Atlantic. The fall/winter 2024 collection, a nod to LA’s Free Jazz movement, honored Akua’s late father, a musician who played alongside renowned acts like Sun Ra and Alice Coltrane. The designs are deeply researched and story-driven, making their garments feel like a wearable archive. It’s clothing meant to be appreciated, displayed and reborn in a way.

The artists in these films are like time travelers who venture to the past to help us imagine what the future could be like. They bring their family history and healthy skepticism about the world to the table. It’s what happens when Black aesthetics enter canonical spaces and disrupt them through storytelling.