Read more of Kim Lawton’s March 12, 2008 interview with the Reverend Victoria Sirota, Canon Pastor and Vicar of the Congregation at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York City:

Q: How important is Easter on the Christian calendar?

A: Easter is the pivotal feast day. It is the most important day of the year for a Christian. The awesome thing about Easter is the way in which it takes what would have been a tremendous tragedy, the death of Jesus on Good Friday, and turns it into the great triumph of God over death, and that changes everything for us. We wouldn’t be Christian if it wasn’t for that … It was what turned the disciples into Christians, when they realized that Jesus was raised from the dead, that he really was the Messiah that they were waiting for and that somehow the world changed in that magnificent sacrifice. That was what gave them the energy, the joy to go out and to preach the Gospel to all people, and many of them were martyred because of it. So that deep, profound faith in themselves and the deepness of who they were was what sustained them in times of their struggles and their trials. A theology or a philosophy that doesn’t deal with death is not going to be helpful to you when you’re in times of suffering and trial. I often find that people talk very nonchalantly about God and religion, and I sometimes think to myself, well, wait until you have difficulties. What will sustain you? The power of the crucifixion is the fact that it was a horrible way to die. That Jesus allowed himself to be killed that way — he could have avoided it if he wanted to. There are other times in the Bible where it talks about the leaders and authorities and people trying to stone him, but he went back to Jerusalem knowing that he had so stirred up the people and the authorities that they were so angry at him that they wanted to crucify him, and he knew that was what he needed to do, so he did it out of his own free will. The pain of that, the sorrow, the struggle, the conflict of that horrible day all turn into joy with the knowledge that he was resurrected from the dead. So suddenly what had been a great failure — the greatest tragedy, the worst thing that could have happened — became the greatest joy, the most wondrous thing, the great triumph of God over death.

Q: How important is music to this season?

A: We know that Jesus, when he met with his disciples on what we call Maundy Thursday — it comes from the Latin mandatum, a mandate, and the mandate actually was to wash each other’s feet. The mandate was to serve each other, to love each other as Christ loves us. At this Passover meal that Jesus was sharing with his disciples, he picked up the bread that he had and broke it and gave it to them and said, “This is my body,” and he picked up the cup of wine and thanked God and said, “This is my blood,” and passed it around. Little did they know that this was going to be the last meal with him. What they knew was that he was very emotional and that he seemed to be telling them things that they knew they needed to remember. One of the last things they did in this celebration of the Passover meal was to sing a hymn. We don’t know what hymn it was, but it would have been a Hebrew chant that would have been sung at the Passover table, and knowing that Jesus was a singer and that he sang with his disciples makes you realize how ancient this form is and how deeply it is engrained in the soul.

Hymns are one of the oldest things we human beings do together communally. What’s wonderful about singing is that you actually breathe together. You say it in the same tempo. It’s the difference between saying a creed together in church, where ir might not be exactly the same tempo, or actually singing it, where everyone has the same tempo. You’re breathing at the end of the phrase together. It is a wonderful moment where we become one. In Christianity we talk about being one body in Christ, and to be able to breathe together and sing together as one is one of the most profound ways to experience that.

The wonderful thing about hymns is that they are encoded with different memories of singing them in different places. I imagine that the disciples remembered that hymn hauntingly the next two days, that they remembered him singing with them, and it probably made them cry as they remembered. And then, when Jesus was resurrected from the dead, then that singing with him became something else. Probably for the rest of their lives they could always see him and hear him singing with them whenever they sang that hymn. That’s the power of music.

The other thing that happened at this Passover meal is that Jesus surprised them by getting down on his knees in front of them, by taking a towel and actually washing their feet. Peter, one of the disciples, immediately said, “No, No, you shouldn’t be washing my feet.” And Jesus said, “If I don’t wash you then you are not part of this whole thing,” and then he said, of course, “Well, then wash everything.” And Jesus said, “No, only the feet.” But this simple, very powerful act of not being the kind of leader one would expect, not being the kind of person who would lord it over them — “Yes, I am God” — Jesus never did that, and that was the most amazing thing, that he of his own free will gave up his life, knowing that was the only way to break the power of death, to be the one who did not deserve to die, but who died in our stead.

Q: What does knowing that Jesus sang with the disciples do for you, and how does that make the importance of music central to this season in the church year?

A: Knowing that Jesus sang meant that he was like me, that I sing, he sang, that he was a fully human being, and that he enjoyed being with people and singing together. One of the greatest things about singing is the way in which it immediately creates community. If you’re breathing together with each other, if you’re singing the same words, you’re experiencing the same feeling. There’s a way in which different hymns give us a different sense of emotion. So, for example, with “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” it is a very personal piety: “Sometimes it causes me to tremble.” Well, if you’ve been in profound grief, you know what that is. That hymn may sound silly to you when you’re in a good mood, and everything’s going fine. But when someone close to you dies suddenly, lingering on the words “Sometimes it causes me to tremble, tremble, tremble” will be exactly where you are. So the hymn picks up an emotion and carries it to a place where we can share it with others in a way we don’t do otherwise. Some of the great moments of hymn singing have been at the funeral of some great, tragic figure. When we sing together “O God Our Help in Ages Past,” there’s something comforting about singing a hymn that has gone through many, many, many different tragedies and carries us together at that moment … We seek to be in community with each other, and singing is one of the greatest ways to allow us to do that, where we can feel the same emotion, and we can say the same words at the same time, and we can truly be one body.

Q: There is special music for this season that most Christians don’t usually sing at other times of the year.

A: One of the great hymns, “Jesus Christ is Risen Today,” was actually a Latin hymn. I believe it dates back to the 14th century. It started in Bohemia. It became very popular, and there’s version of it that came in 1708 in English translation, and we’re still using that hymn and that melody. It is ecstatic in the way that you have “Alleluia,” which is “praise to God,” and that alleluia repeats after every phrase, so it gets the sense of total joy. If you’ve ever been with somebody you thought was dying, and then they make it through the night, and the doctors refer to it as a miracle, that’s the kind of joy which was, “We thought he was dead, but now he is alive. Hallelujah!”

Q: Much Easter music uses alleluia or hallelujah. Why is that?

A: “Alleluia” is the Latin form of “praise to God.” “Hallelujah” is the Hebrew form of “praise to God.” They’re both ecstatic, and I think the sound of it is why we haven’t translated them, because “Alleluia,” the way it falls off the ear, and “Hallelujah” — just that sense of almost moving into the non-verbal, not a translation of “praise to God” but “Hallelujah,” that sheer joy, sheer ecstasy.

Q: And why are those words used especially at Easter?

A: Not only do we use them especially at Easter, but we don’t say them in the Christian Church during Lent. We bury the alleluias and return them on Easter Sunday because we are walking with Jesus through this Lenten period. One of the earliest services in the Christian Church is the Easter Vigil, waiting through the night, being reminded of the great story and waiting for dawn to come, waiting for that moment when Christ is risen. And the early church then began to precede that with two fast days, so you’re having a Paschal fast before the Paschal feast, and eventually, within a number of centuries it became a whole week, what we now term Holy Week … During Lent we work on our relationship with God and prepare ourselves to get to the point each year so that we can walk with Jesus during these final three days. The gift of the Triduum Sacrum, these three holy days, is that we walk in real time with Jesus, and we meditate on everything that happened to him during those times.

Q: How does the music of the season reflect that journey, those moods?

A: The songs and the hymns, especially for Good Friday, reflect the pain, the conflict, the torture, the incredible sadness and mourning around the death of someone you love. Any of us who have had that kind of experience know that it’s like having the rug pulled out from underneath you. You can’t imagine the world without this person. You can’t imagine going on. Your life has totally changed.

In “O Sacred Head Now Wounded” we have a wonderful hymn. It started as a Latin hymn. It got translated into German and then into English. One of the early English translations was “O head so full of bruises,” which I don’t think we’d still be singing today. But the translation, the music, the harmonization — what’s so wonderful about it is the way it holds complex theological issues together. There are moments in major keys, moments in minor keys, there are dissonances and consonances, there is tension that gets resolved. It takes you on a journey, takes you on a long journey through the text. It’s a meditation on Christ and on his body, specifically his head and on the gift of his sacrifice, so encoded in the music, in the sonorities, in the choice of chords, in the way in which the melody moves, in the way in which the harmony flows. We hear the anguish and that suffering, and we linger with it. “O Sacred Head Now Wounded,” if you sing all the verses, takes a long time, and in general the songs we sing on Good Friday are longer. They are slow, they may be in a minor key, they have a sense of suffering, of sorrow, of mourning, and that is a great gift. To be able to stand together in that emotion and do it together as a body is the gift to us. If you’ve been to a funeral, where suddenly everyone is singing together, there’s something very comforting about that, that you’re not alone. Death happens to all of us. That is one of the great tragedies of being human.

Q: And then there is a big contrast from the emotion of Good Friday to Easter.

A: I don’t think anyone can tell you that you must believe Jesus rose from the dead. I think that we all struggle with that in our own time … I’ve been through all the doubt, so I understand why people can’t just say, “Yes, this is for me.” But I also know in my heart that my Redeemer lives, that I’ve seen miracles surrounding the deaths of good friends of mine, and I know that there’s something more than what we see. I know somehow that the invisible is louder than the visible, that there are saints and angels that sing their praises. So on the Sunday morning of Easter, the cathedral is totally changed from Good Friday. On Good Friday, it’s been stark. We’ve cleared off the altar; there is little there. We have the cross, the starkness of the cross, and the sadness — no flowers, no incense. And then on Easter Sunday the church is filled with lilies and spring flowers. The smells are overwhelming, the incense comes back, the lights are up high and bright, the music is loud and joyous and fast and fills us with such happiness to know that our God lives, that love has triumphed over evil.

Q: How does the music convey the Easter message?

A: The theology of Easter is one of joy, triumph, resurrection, rebirth, surprise. The joy of Easter is in the triumph of the resurrection. It’s an incredible and profound joy knowing that God has broken through and that love has triumphed, and so the music tends to be more straightforward, less lingering on harmonies and dissonance, very straightforward, a joyous, faster tempo … One of the things people love about Easter hymns is the incredible joy and happiness of singing them. The tempi are faster. The organ plays loud. We can let ourselves sing at the top of our lungs, and no one is going to yell at us for singing loudly. We have ecstatic moments and hallelujahs. We have just the sheer joy of knowing that love has triumphed. The message of Easter is encoded in the music. We hear the joy, we hear the triumph. We sing fast music, we sing it joyously, it’s in a major key, and it helps us to feel that this is the day the Lord has made.

Q: How is the message expressed differently in different cultural and theological traditions?

A: Every hymn is the result of someone’s spirituality. What’s so interesting about hymn writing and hymn composing is that we take together a text, sometimes it’s a Latin text from the 12th, 13th century, it’s connected with a translation, it might be translated into German and then into English. We have the piety of all those people who are working on that. We have a tune. We have someone else who might harmonize it. All of these pieces fall into place. It is always a miracle as to which hymn people decide is the one they want to sing. “Jesus Christ Is Risen Today” was a hit tune the moment it appeared in 1708 in its current form, and we have been singing it every Easter since. This wonderful hymn “Because He Lives I Can Face Tomorrow”: Being able to have that as your core theology, singing it so that you remember it, so that it’s in your mind the rest of the week, waiting to sing it until Easter Sunday, and that is a profound theology. That’s absolutely helpful to you, and so as you have that tune going through your head the rest of the week, you’re thinking about the Easter message, the core message, which is Jesus lives, Jesus was resurrected, therefore my life has a new meaning. Death is not the end of me.

Q: At Easter time, there are traditional hymns that are sung pretty universally, but there are lots of new songs as well, much more so than Christmas. What does this say theologically?

A: It actually is terribly theologically important that we keep composing and writing new music. If we stick with all the old music, then somehow there lingers this idea that God is dead. The Holy Spirit in my theology is still moving in the world and is still encouraging us to write new songs, to write new texts, to write new poetry, and the gift of a living faith is rediscovering again what that means for you … What we love about something new is that we see an old idea or an old truth with new eyes, and that’s a great gift to the world. So we absolutely need new Easter hymns, new Easter songs, and it’s lovely that these different traditions all have their own hymns that pop up.

Q: So many of the Easter songs have the image of Jesus as a lamb.

A: Jesus and his disciples had that Passover meal, and at that they would have had lamb. The sacrificial lamb is deep in Jewish theology — the idea of one sacrifice representing the sins of all. And so that was an obvious thing for the early church to come to, the idea of Jesus being the paschal lamb, being the lamb of Pesach, of Passover, and because of him our sins are passed over. In the early church, the idea of crucifixion was so horrendous; it was such a horrible way to die that they couldn’t imagine using that as a symbol. Constantine saw a vision of the cross in the sky before he overcame his enemies, and two years after that he decided crucifixions should be banned. There is no symbolism of crucifixions or crosses in the fourth century or the fifth, and it’s only later that people began to portray that, when it’s not a form of death, a form of execution that’s being used all the time.

Q: And the Hallelujah Chorus. Why is that such a common staple of Easter music?

A: I think the Hallelujah Chorus, which comes from Handel’s Messiah, somehow represents the sheer ecstasy of the joy of knowing that our life has meaning, of knowing that love has triumphed, of knowing that God is and that there is more to life than just the dreariness of the day — that Christ has triumphed over death, that we can hope for greater things, that there is life after death. There are some hymns and songs that seem fine on paper, but when you sing them they don’t resonate, and then there are other hymns and songs that the first time they are sung, somehow everybody knows this speaks an eternal truth. “Jesus Christ is Risen Today” is one of those hymns.

Q: Many of the Good Friday and Easter songs emphasize blood.

A: The truth of the reality is that we are dealing with life and death issues. The idea of blood, which is so horrifying — when you bleed you are terrified that you are going to die — but to use that as a symbol, then, of new life is the gift of it as symbol. There is much poetry that is written that seems sort of gory, but the best of it transcends that and calls us to a different place. It reminds us that yes, we are human and that we die: Dust to dust, ashes to ashes. And yet it reminds us that there is another side to that, that the story doesn’t end there, that we end in resurrection.

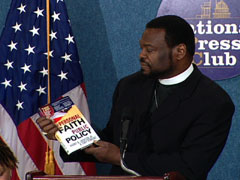

LAWTON: As president of a group called the Hip-Hop Caucus, Yearwood focuses on getting young people involved in advocacy. There was this hip-hop concert, cosponsored by Amnesty International, to raise awareness about people displaced both by Katrina and by the war in Iraq.

LAWTON: As president of a group called the Hip-Hop Caucus, Yearwood focuses on getting young people involved in advocacy. There was this hip-hop concert, cosponsored by Amnesty International, to raise awareness about people displaced both by Katrina and by the war in Iraq.

CHOIR #1 (singing): And He shall reign forever and ever.

CHOIR #1 (singing): And He shall reign forever and ever. Mr. TYLER: We want to skip over the sorrow. We want to skip over the abandonment and go get our praise on. But, if you don’t remember what he went through, then I feel your appreciation for the significance of that resurrection is marginalized.

Mr. TYLER: We want to skip over the sorrow. We want to skip over the abandonment and go get our praise on. But, if you don’t remember what he went through, then I feel your appreciation for the significance of that resurrection is marginalized. LAWTON: Another widely sung hymn is “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” — an old African-American spiritual.

LAWTON: Another widely sung hymn is “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” — an old African-American spiritual. LAWTON: And so comes the great transition to Easter Sunday, from mourning to resurrection.

LAWTON: And so comes the great transition to Easter Sunday, from mourning to resurrection. Canon SIROTA: Because He lives, I can face tomorrow”. And that is a profound theology.

Canon SIROTA: Because He lives, I can face tomorrow”. And that is a profound theology.