Read more of our interview with Dr. Robert Franklin, President of the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta:

Q: What do you think Howard Thurman’s theological legacy is?

A: Thurman I think connected activism and agency for social change to spiritual renewal. I think he was really a genius at holding together in thought and in his own practical existence a focus on social and personal transformation.

Q: Was that unusual in the African-American experience at that time?

A: To some extent, because I think that so much energy had been focused on the civil rights movement and the work for racial and economic justice in this country. A lot of clergy were focused on changing laws, changing institutions, changing government policy, and externalities. And Thurman began to challenge these clergy never to lose their rooting in spiritual practices such as meditation, prayer, singing, celebration and worship, and silence — the important discipline of listening and listening deeply and carefully. That was an unusual note to have sounded during the rancor of the civil rights movement.

Q: And was that a controversial note to sound?

Q: And was that a controversial note to sound?

A: It was. In many respects, Thurman was marginalized by many church activists and certainly secular political activists who felt: “Well, that’s fine, that’s private stuff, but that’s not a resource for transforming our society.” And Thurman interrupted: “No, but it is. In fact, if we press onward with the activist social agenda and lose touch with our deepest values and our practices of renewal, our rhetoric in public will simply become bitter and shrill.” So he had, I think, real insight into how the movement could continue to be guided by the core values of the love ethic of Jesus.

Q: What were some of his key themes that he seemed to come back to over and over again?

A: The interdependence of all of life, that sense of profound connection between all faith traditions, between all peoples and all cultures was one of the big themes in Thurman’s life, and it certainly had a profound impact on all those who read and followed [him]. The sense that life is a journey, and that as we travel we meet people who assist us on our journeys, and we are assisting others in arriving at their destinations. So that metaphor of journey and having strength for the journey is an important one in Thurman’s thought. Clearly, the practical spiritual disciplines that have always been central in Christian traditions, I think, had begun to fade a bit, and he refocused attention on the importance of time alone, of quiet. He has a wonderful metaphor that he used, the notion of centering down, of finding and reconnecting with one’s own center. And one can almost hear the hints of both Hindu and Buddhist accents in forming his own very vital Christian theology. It was a wonderful openness to other traditions. For Thurman there were not strangers in the world. He really took [seriously] the notion of the human family as a single family — as one family, but there are simply family members we have not yet met.

Q: Were some of those themes, especially being open to others, revolutionary for the time? Is that why his message didn’t seem at the time to be distributed as widely as it may have been?

A: I think so. I mean, let’s face it, this was an African-American clergy-person and theologian in the 1950s articulating this message at a time when many black church leaders and many progressive white church leaders and Jewish sympathizers were very active in the civil rights movement, but [they] had a very narrow focus on external social change. And here was Dr. Thurman, a Southern, black, Baptist clergy-person talking about openness to insights from other faith traditions and working with all kinds of people. It really upset the equilibrium of a lot of his audiences. And they didn’t quite follow Thurman as far as he wanted to take them. But the benefit was that this Southern, Baptist, African-American clergy-person found himself in the rather extraordinary locale of Boston University, a place where I think some of his maturest thought was developed during those years. His opportunity to interact with that extraordinary and cosmopolitan, diverse community in New England, I think, was an important opportunity for him to expand even further. And we see the fruition of all of that intellectual growth in the ministry he led and developed in San Francisco.

Q: He seems to have touched so many people, and yet there’s a sense in which he is not that well known, especially today. Why do you think that is?

A: Well, I think the academy has not been very generous to Dr. Thurman, unfortunately. Only now are we finding Thurman’s voluminous writings in the seminary curriculum throughout the country, and that’s refreshing after a long period of neglect. In times to come, I think younger clergy will be very attentive to the distinctive voice that Dr. Thurman brings to the academic theological enterprise. Thurman was really reaching beyond the boundaries of narrowly circumscribed academic theology and was in touch with practices like mediation and prayer, in touch with non-Christian traditions; a more holistic, comprehensive enterprise is at work in his thinking. We will see future generations of clergy and the general public discover this wonderful resource, this Christian mystic, this activist, this man who taught us to listen more carefully and more deeply to important resources in our lives, and to discover and respect nature. I think those who are ecologically sensitive and sophisticated will find in Thurman wonderful tropes and poetic imagery and insights that we need to integrate into today’s theology.

Q: Do you think there’s more resonance today for some of the things that he touched on than there was when he was writing?

A: I think there is greater resonance today for many of the things in his thought, which only goes to show us that Dr. Thurman was way out ahead of his generation, and in fact he was a 21st-century theologian working in the middle of the 20th century.

Q: Why do you think he was bypassed by the academy?

A: I think he was eclipsed, to some extent, by younger, more vocal leaders. I mean, there was Martin Luther King, Jr. after all. And Dr. King’s voice really dominated the movement of the ’50s and ’60s. Dr. Thurman didn’t spend a lot of time marching and in the streets, but was focused on building a congregation, writing books, engaging in meditation and prayer and leading smaller groups of people through spiritual disciplines, through personal change and renewal. He never really aspired to become a great pulpit theologian and one of the better-known preachers of this country. Generally, Americans don’t have a lot of patience for or interest in academic theologians, and I think he was more comfortable in that zone, as he often put it, thinking long thoughts and uttering long prayers.

Q: What about his relationship with Dr. King? How influential were Thurman and his writings on King’s theology and his activism?

A: There is clearly a direct line of connection and influence — in Dr. Thurman’s own personal journey, his writings and his preaching, and in the chapel of Morehouse College, where Dr. King encountered Dr. Thurman as a public voice, a public theologian. But of course, Dr. King, through his father, Daddy King, knew Dr. Thurman, and there were those familial connections and conversations. And then, of course, later, moving to Boston University, again Dr. King was able to follow in that stream that Thurman was developing there. There were a lot of influences, particularly this notion of the interdependence of human existence — that all of life is characterized as a network of interdependence and connection and, again, the openness to Eastern forms of theology and religious practice. The openness to Mahatma Gandhi, the travels to India — I think Dr. King was directly influenced by Dr. Thurman’s having paved that path in advance.

Q: For seminarians and other people from a new generation, what would you like them to learn from Dr. Thurman’s writings?

A: That God embraces all of God’s creation. And while it sounds simple at first blush, it has rather profound ethical implications — that we are to work hard at reconciliation and overcoming the estrangement between nations, groups, peoples. That was [Thurman’s] life — overcoming differences, building bridges, scaling the walls that humans have so effectively created. I would like for my students to be more attentive to the fact that they are called not simply to be sectarian theologians who mouth the truths of particular traditions, but to apprehend that large reality that Dr. Thurman was so tuned in to, to be responsive to it, to try to guide and shape it. And I think Dr. King proved in his life that ultimately that’s what all clergy-persons are called to. Rather than limiting our focus to an immediate, specific context, we should see its connection to the larger struggle. I love the bumper sticker that says, “think globally but act locally.” That was in part Thurman’s genius.

Q: You told me that after September 11th you found yourself turning again to Thurman’s book, “Meditations of the Heart.” Why was that? What did you find there that particularly connected [you] to the events of September and afterward?

A: In the post-9/11 era, I think that America has been grappling with four major agendas: We are healing. We are fighting back against opponents. We are reckoning with why this happened. And we’re rebuilding and projecting a better future, not only for our nation but for the world. I find all four of those themes addressed in “Meditations of the Heart.” Dr. Thurman simply thinks about the rhythms of a life, of a year, and really speaks to every moment in the human life cycle, from childhood to old age and death, through the rhythms of the Christian calendar year, and names those times when healing is the order of the day, or when readying ourselves to oppose evil and to thwart the efforts of those who mean us harm or those who are enemies of democracy, when the focus is on reckoning, discerning and listening carefully and understanding why things occur as they do in our world. And then, of course, [there is] the whole agenda of building a better world, a better future. “Meditations of the Heart” is, for me, really the book for this season as we engage in those processes.

Q: You talked about overcoming evil. There’s also a sense that suffering is part of that rhythm of life as well. That’s something that we don’t always hear about in America.

A: Indeed. Thurman really understood the goal of suffering in human existence — the purifying, focusing impact that suffering has. And he also understood very profoundly this concept that Dr. King later articulated but Thurman wrote about first — that unmerited suffering could be redemptive for other people; that the suffering of the innocent, of Jesus on the cross, this innocent victim, of King and other civil rights workers who were innocent but who lost their lives and were given as sacrifices in the struggle for a better world. That’s powerfully redemptive, both for those who are the immediate beneficiaries of their sacrifices, but even, Thurman argued, to so-called opponents and enemies who observe the witness of that sacrifice. That’s a controversial theological claim, but Thurman felt that suffering could speak very powerfully to all kinds of people.

Q: What about life or healing coming out of that as well? How did Thurman weave that into the whole rhythm?

A: Well, I think he saw that suffering is like a seed that, in its time, opens and unravels and evolves and yields new life and new-found strength and new-found hope and courage to go on, with the memory of past suffering as a resource for the journey ahead, with the sense that we must never, never again go back there or experience that kind of tragedy and evil. We must learn from it. We must alter our own action today and try to organize a world such that past tragedy is never again called for. Suffering had this evolutionary and educative power to guide us and push us outward into a better future. In all sorts of ways, Thurman’s insight about the nature of human failing, human limitation, human tragedy is a resource for those of us who are trying to reckon with the evil in the world, with war, with violence against innocent people, and trying to learn from that, but as best we can and as rapidly as we can [trying to] bring an end to such violence.

Q: In December, Ebony Magazine republished a Christmas poem by Thurman. Johnny Cochran’s new biography mentions Thurman, and [there are] many others. Do you think that would surprise him, that he’s getting this new attention in popular culture?

A: I think it would. I think he would chuckle to discover that a crusty old theologian who had his own immediate devotees and loyal followers, but never expected to become a pop icon, is now being embraced and discovered by all sorts of people– and younger people. It’s a wonderful thing to see. I just hope more people will pause and visit a library or book store and pick up “Meditations of the Heart” — a good one to start with because it’s a sampling of the wit and wisdom of Howard Thurman and offers a real feast in bite-sized segments of the kind of profound insight into life that one of our great 20th-century theologians possessed.

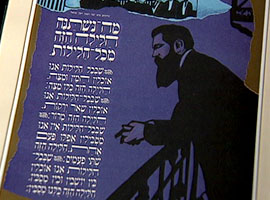

DAVID WACHTEL (Jewish Theological Seminary): It’s the quintessential tale of the Jewish people, it’s their foundation document; it’s how Jews know they’re Jews, even those who don’t believe it happened. In countries where Jews were not permitted to practice their religion, [they] risked death by baking matzot, having Haggadot, and participating in Passover rituals.

DAVID WACHTEL (Jewish Theological Seminary): It’s the quintessential tale of the Jewish people, it’s their foundation document; it’s how Jews know they’re Jews, even those who don’t believe it happened. In countries where Jews were not permitted to practice their religion, [they] risked death by baking matzot, having Haggadot, and participating in Passover rituals. Haggadot reflect the different customs and traditions of the different communities they served and of course they reflect the different languages. My favorite title of one is the “Haggadah for a Liberated Lamb,” which is a vegetarian Haggadah.

Haggadot reflect the different customs and traditions of the different communities they served and of course they reflect the different languages. My favorite title of one is the “Haggadah for a Liberated Lamb,” which is a vegetarian Haggadah.

A conversation now on Enron ethics. Reverend Jim Wallis is the editor-in-chief of SOJOURNERS magazine in Washington. In New York, Larry Zicklin is a former managing partner at the brokerage firm of Neuberger Berman, and a professor of business ethics at New York University. In California, Kirk Hanson is executive director of the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University and was formerly a professor at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford.

A conversation now on Enron ethics. Reverend Jim Wallis is the editor-in-chief of SOJOURNERS magazine in Washington. In New York, Larry Zicklin is a former managing partner at the brokerage firm of Neuberger Berman, and a professor of business ethics at New York University. In California, Kirk Hanson is executive director of the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University and was formerly a professor at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford. Professor KIRK HANSON (Markkula Center for Applied Ethics): I see this as a case of the ethics of new economy companies. This is an issue where in the new economy we have released many of the regulatory constraints, we’ve permitted a lot of experimentation. And unfortunately, in the process of doing that, executives have taken advantage of some of their newfound freedom. And I think the untruthfulness and stretching the bounds of acceptable behavior has resulted.

Professor KIRK HANSON (Markkula Center for Applied Ethics): I see this as a case of the ethics of new economy companies. This is an issue where in the new economy we have released many of the regulatory constraints, we’ve permitted a lot of experimentation. And unfortunately, in the process of doing that, executives have taken advantage of some of their newfound freedom. And I think the untruthfulness and stretching the bounds of acceptable behavior has resulted. Prof. ZICKLIN: I think it is a national problem. I think Enron may be the most egregious case. But when you look at this management, who for the last few years were taking great responsibility for what was happening at the company, the great success they enjoyed — being on the cover of every magazine, in the newspapers, being interviewed on television — suddenly now appearing before Congress and saying, “We didn’t know, we didn’t see, we weren’t part of it, we didn’t understand.” I mean, that’s a lack of responsibility. That is total irresponsibility.

Prof. ZICKLIN: I think it is a national problem. I think Enron may be the most egregious case. But when you look at this management, who for the last few years were taking great responsibility for what was happening at the company, the great success they enjoyed — being on the cover of every magazine, in the newspapers, being interviewed on television — suddenly now appearing before Congress and saying, “We didn’t know, we didn’t see, we weren’t part of it, we didn’t understand.” I mean, that’s a lack of responsibility. That is total irresponsibility. Rev. WALLIS: By saying that this is not just a business scandal or even a political one, but it is a cultural issue here. I hope it is a seminal event. My question is: Where do Enron executives go to church? And are they hearing on Sunday mornings or Saturdays in their houses of worship, are they hearing preaching and teaching that talk about moral issues of economy? When this moves from a Sunday morning issue to a Monday morning question and back and forth, that’s when it becomes, I think, a serious conversation.

Rev. WALLIS: By saying that this is not just a business scandal or even a political one, but it is a cultural issue here. I hope it is a seminal event. My question is: Where do Enron executives go to church? And are they hearing on Sunday mornings or Saturdays in their houses of worship, are they hearing preaching and teaching that talk about moral issues of economy? When this moves from a Sunday morning issue to a Monday morning question and back and forth, that’s when it becomes, I think, a serious conversation.

Q: What did he say to you to prompt that change?

Q: What did he say to you to prompt that change? Q: And was that a controversial note to sound?

Q: And was that a controversial note to sound? Dr. RICHARD SCHWARTZ (Pediatrician and Researcher): There are a lot of medicines out there that have never been tested on children so it leaves the doctors high and dry in a legal quagmire, using them without FDA approval because they have evidence above 12, above 18, but not for younger children.

Dr. RICHARD SCHWARTZ (Pediatrician and Researcher): There are a lot of medicines out there that have never been tested on children so it leaves the doctors high and dry in a legal quagmire, using them without FDA approval because they have evidence above 12, above 18, but not for younger children. Dr. MURPHY: We are finding out so many important things in products, some of which have been used on children for years. So we think it is very vigorous and healthy as long as we’re careful.

Dr. MURPHY: We are finding out so many important things in products, some of which have been used on children for years. So we think it is very vigorous and healthy as long as we’re careful. Professor ADIL SHAMOO (University of Maryland School of Medicine): By definition, research is non-therapeutic it means you are testing something brand new and you don’t know its outcome regardless of what they claim in their advertisement that this medicine is better than the existing medicine.

Professor ADIL SHAMOO (University of Maryland School of Medicine): By definition, research is non-therapeutic it means you are testing something brand new and you don’t know its outcome regardless of what they claim in their advertisement that this medicine is better than the existing medicine. But there were serious problems. Some families brought suit against the NIH — one for a wrongful death. At one point, Linda’s son almost died.

But there were serious problems. Some families brought suit against the NIH — one for a wrongful death. At one point, Linda’s son almost died. Generally, the more classical dances are devoted toward the gods, and on this occasion probably more toward Rama.

Generally, the more classical dances are devoted toward the gods, and on this occasion probably more toward Rama.