Under the leadership of President Michael Crow, Arizona State University is encouraging more students to get college degrees by preparing students for higher education as early as pre-school, and by making college more affordable. Crow hopes more schools across the country follow ASU’s example. “I think public universities have got to step up and say we’re going to figure this out,” he suggests. “We’re going to figure out how to serve the nation.”

Author Archives: Fred Yi

Parliament of the World’s Religions

The 2015 Parliament of the World’s Religions, the oldest and largest interfaith gathering in the world, was held October 15-19th in Salt Lake City. Some 10,000 participants from 50 spiritual traditions participated. The event was first held in Chicago in 1893. This year’s gathering focused on peace, climate change, and women in leadership. Imam Malik Mujahid, who chairs the Parliament’s board of trustees, described the event and why he believes it is important for people of faith to gather in solidarity and believe in “the humanity of the other.”

Nostra Aetate 50th Anniversary

The 1965 Second Vatican Council declaration on the relation of the church to non-Christian religions transformed church doctrine about Jews and other faiths. Nostra Aetate had its roots “in the shame and realizations of Christians after the Holocaust for what has been done to Jews,” according to Rev. Dennis McManus, a consultant for Jewish affairs at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and a member of the faculty of the program for Jewish civilization in Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service.

Rev. Dennis McManus on Nostra Aetate

Watch additional video clips of Kim Lawton’s interview with Rev. Dennis McManus of Georgetown University about the relationship of Catholics and Jews after Nostra Aetate.

Rev. McManus tells how, after a visit to Auschwitz, the late Cardinal James Hickey was moved to set up joint Catholic-Jewish projects.

Nostra Aetate paved the way for the Catholic Church to enter into dialogue with other religions.

What was the pre-Nostra Aetate Catholic “teaching of contempt” about Jews?

How did Pope John Paul II’s childhood in Poland help to improve Catholic-Jewish relations after Nostra Aetate?

Rev. MacManus says Christians still owe Jews a debt for centuries of anti-Semitism.

Rabbi Noam Marans on Nostra Aetate

Watch additional video clips of Kim Lawton’s interview with Rabbi Noam Marans of the American Jewish Committee about the legacy of Nostra Aetate.

Rabbi Marans describes pre-Vatican II animosity of Christians toward Jews.

After the Holocaust, Christians began to rethink their relationship with Jews.

How were the principles of Nostra Aetate implemented by several popes?

Nostra Aetate “enabled Jews to look at Christianity on its own merits.”

What was Nostra Aetate’s impact on Christianity?

John Garvey: Extraordinary Yet Ordinary Nostra Aetate

The impact of Nostra Aetate over the last five decades has been extraordinary. Perhaps the greatest sign of this is that to young people, like undergraduates at my university, Nostra Aetate doesn’t seem extraordinary at all.

These young men and women find nothing strange in the idea that “God holds the Jews most dear for the sake of their fathers,” as Nostra Aetate teaches. Before they were born, St. John Paul II had already visited the Roman synagogue to pray with the Jewish community. In their lifetime Pope Benedict XVI developed the scriptural interpretation that underlies Nostra Aetate’s teaching on Jewish–Christian relations. Pope Francis co-authored an interfaith reflection on faith and family with a Jewish rabbi and close friend before his election to the papacy. Young people today have never known a church that does not recognize the Jews as the “root of that well-cultivated olive tree onto which have been grafted the wild shoots, the Gentiles.”

Nostra Aetate is not a fait accompli. “In our time,” the declaration begins, “the Church examines more closely her relationship to non-Christian religions.” In our own time, we must continue the interfaith conversation that Nostra Aetate began. The particular challenge of our own time, I think, is to remember that the goal of this dialogue is not simply tolerance but truth. In the search for common ground that Nostra Aetate calls for, there can be a temptation to give ground, to allow that one vision of reality is as good as another.Nostra Aetate exhorts us to recognize in other faiths what is true and holy. This is not tribalism. The purpose of interfaith dialogue is to strengthen unity and love among men. But it is the truth that allows us to live in unity and harmony. It is our pursuit of truth, with confidence that it will be found, that unites us in interfaith dialogue.

John Garvey is president of the Catholic University of America.

Jonathan A. Greenblatt: How Nostra Aetate Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations

The promulgation, on October 28, 1965, of Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on the Church’s Relations with Non-Christian Religions, may be the most important moment in post-Holocaust Jewish-Christian relations and interfaith relations writ large.

In its fourth chapter, Nostra Aetate effectively overturned centuries of what the noted French Jewish historian Jules Isaac termed “the teaching of contempt,” namely, that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus and therefore they had been rejected by God and their covenant revoked. The devastating effect this theological teaching had on Jewish communities through the centuries has been well documented by historians, and while it is essential to differentiate between Christian anti-Judaism and Nazi anti-Semitism, without the former the latter would not have been possible.

In light of this history, the Church’s unequivocal declaration that the Jews should not be held accountable for the death of Jesus and its repudiation of anti-Semitism were truly revolutionary. The affirmation that “God holds the Jews most dear” and the call for mutual understanding and dialogue inaugurated a new era of positive relationship and engagement that, mere decades before, was inconceivable. In the past 50 years, the Church has continued the process that began with Nostra Aetate. It has developed a sophisticated theology of Jews and Judaism expressed in documents like “We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah” (1998) and “The Jewish People and the Sacred Scriptures in the Christian Bible” (2001).

Another important moment was the Vatican’s recognition of the state of Israel and the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1993. While some details of the formal agreement between the two sovereign nations remain to be worked out, the forging of bonds between Israel and the Holy See is deeply meaningful for the Jewish people.

In the years since 1965 there have been moments of tension and conflict. All relationships require hard work, and misunderstandings are inevitable. The commitment of both Jews and Catholics to overcoming the past, and especially the warm personal relationships that have developed at the highest levels as well as locally, have made constructive engagement and honest exchange possible, even about difficult subjects. The relationship is strong enough that it has continued despite unresolved issues, such as the opening of the Vatican archives from the Second World War and the proposed canonization of Pius XII.

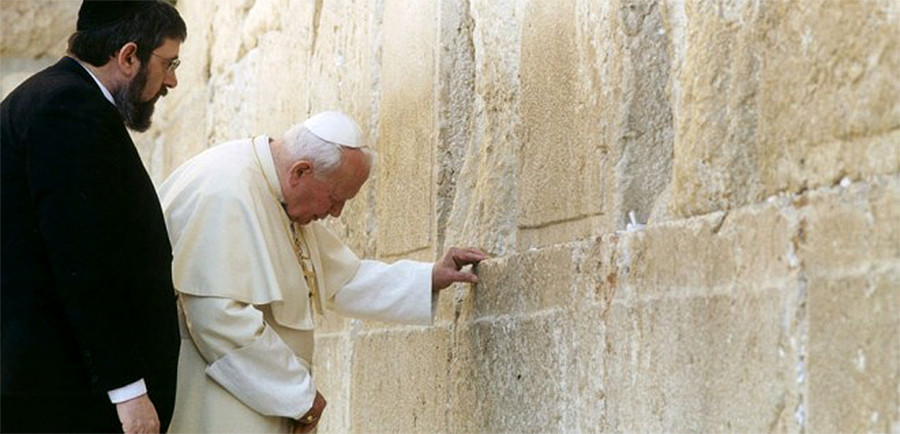

We are now in the fifth papacy since the promulgation of Nostra Aetate. Each pope has, in his own way, added to the structure that has been built over the years. John Paul II’s visit to Israel in 2000, including his moving meeting with Holocaust survivors at Yad Vashem and his placing a prayer of apology for past wrongs committed by Catholics against Jews in the Western Wall in Jerusalem are emblematic of the essential role of the popes in Catholic-Jewish reconciliation. The friendship of Pope Francis with Rabbi Abraham Skorka is itself one of the fruits of Nostra Aetate and a model for Jews and Catholics around the world.

We live in a world in which religion is often seen as the cause of discord and violence. Nostra Aetate and the new relationship between Jews and Catholics prove that, even after two millennia, religious hatred can be overcome.

Jonathan A. Greenblatt is CEO and national director of the Anti-Defamation League.

Mexico Migrant Center; Novelist Geraldine Brooks

Casa del Migrante offers safe harbor to those fleeing violence and poverty in Central America; and a new novel focuses on the flawed biblical figure of King David.

Mexico Migrant Center

Approximately 200 miles south of the U.S. border, in the city of Saltillo, is Casa del Migrante, a shelter for migrants run by Father Pedro Pantoja, a 72-year-old Jesuit priest. The shelter is one of the few safe harbors for refugees crossing Mexico on their perilous journey fleeing violence and poverty in Central America.

Novelist Geraldine Brooks

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Geraldine Brooks has written a new historical novel, The Secret Chord, which focuses on the biblical King David. Managing editor Kim Lawton visited Brooks at her home on Martha’s Vineyard to talk about the writer’s conversion to Judaism, her sense of Jewish spirituality, and what she learned while researching the Hebrew prophets and the story of David, whose life, she says, embodies “the dark and the light of the human condition.”

Excerpt from The Secret Chord by Geraldine Brooks:

Being a father, having an heir, seemed to add an extra dimension to David. He had always been a vivid, animating presence in any room he entered. But now he would come from visiting the boy, whom he had named Amnon, crackling with even greater energy and force. He had been an engaged listener, ready to learn what any man might have to offer in discussion, but now there was an additional depth to his questions, a more far-reaching vision behind his decisions. He thought now beyond the span of years and into a future that glittered ahead into centuries. It’s one thing, I suppose to have a prophet tell you that you will found a dynasty. Now, it seemed, he allowed himself to truly believe it.

…

As the wars dwindled to skirmishes and our strength grew, David as able to spend less time with military commanders and more with the engineers and overseers who were fanning out through the land, digging cisterns, making roads, fortifying, connecting and generally making a nation out of our scattered people.

It was a time when any man could seek and find justice. I think that David’s own experiences as an outlaw, a falsely accused man, had made him resolve to deal justly with his subject now that he had the power to do so. In those years, he never tired of hearing suits, and would listen for hours to all sides of a grievance, taking pleasure in teasing out the threads of a dispute and weighing all the evidence laid before him. Any who felt dissatisfied by the decisions of the elders at their own town gates could appeal their matters to David himself, and know they would be fairly heard.

He composed some of his best music at this time, training choirs to praise the Name in musical rites that drew great crowds to worship. He would join with the choirs at such times, his soaring voice carrying the melody, enriching the harmony, his face lifted up to the heavens and lit by the ecstasy of his ever-renewing bond with the divine.

…

David would wear no purple cloth, no symbols of his kingship, when he went to greet the ark. In its presence, we were all of us servants.

We waited at the city gates as the ark approached. It was sohorhim, the hour of light, when the outriders came into view, cresting the Mount of Olives. The olive trees had turned their leaves so that the bright undersides shimmered. David gave a great sigh of longing, almost a groan. And then, in a wincing flash of brightness, the sunlight caught the gilded wingtips of the cherubim atop the ark itself. The people cheered. David gave the sign, and the choirs he had assembled burst into song. Cymbals, systrums, flutes, lyres, drums—every musician the city possessed—and there were hundreds—had been called to raise a joyful noise to the heavens. Soon, the procession was in the valley, the curtain that shielded the ark rippling in the warm wind. We could hear the voices of the singing men and women, chanting the words David had composed for the occasion: Give praise, proclaim his Name/Proclaim his marvels to the nations/Sing to him, sing praise to him…

David, standing just in front of me, could not keep still. He held his arms out from his sides, his fingers stretching down to the earth, quivering as if some great energy were passing up and through them. He was breathing fast and deep. Suddenly, he raised his chin, and gave a cry—like a paean, but higher, sweeter—rich notes that filled every heart with gladness. The he was loping down the hill, as wild as a boy, as ardent as a lover, his arms outstretched, sprinting toward the ark. When he reached it, he cast himself down in full prostration, his arms stretched out as if in the widest embrace. It was a lover’s moment, between him and the Name, the great One who had blessed him, kept him, and brought him to this moment. I knew how he prayed: I had felt its ardency. Now all his people felt it. I could hear the sighs and the cries all around me, as the power of it moved and stirred the crowd. When David rose to his feet, he did so as if lifted by strong and tenders arms. Then he began to dance.