How the Press Reported on the Atomic Bomb

Inside the headlines and propaganda that shaped America’s view of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - and how the truth finally got out

The first draft of the atomic bomb’s history wasn’t journalism—it was public relations. In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Americans first learned about the bomb not through unfiltered reporting, but through government-managed press releases and tightly controlled coverage. The U.S. government shaped public understanding of the bomb’s power by celebrating scientific triumph, while concealing its devastating human cost.

Central to that effort was William Leonard Laurence, the New York Times’ celebrated science writer who secretly worked for the Manhattan Project. Tasked with drafting official press releases and front-page stories, Laurence helped craft a narrative of technological wonder and moral righteousness—his words defining the nation’s first impressions of the atomic age.

From triumphant headlines and propaganda posters to the suppressed stories of journalists who saw the bombs’ aftermath firsthand, these articles trace how truth itself became one of the earliest casualties of the atomic era.

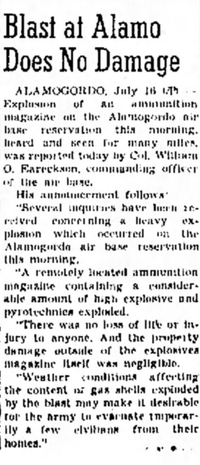

Manhattan Project Press Release

Scientists were unsure what the impact of the Trinity test would be, so in advance of the test, Laurence prepared four possible cover stories, framing the blast with varying levels of severity from a minor accident to a disastrous explosion. The War Department planned to issue whichever version would go over best based on what the public observed. This is the version that ended up being run in dozens of newspapers across the country. “Several inquiries have been received concerning a heavy explosion which occurred on the Almogordo Air Base Reservation this morning,” Laurence wrote, concluding that “the property damage outside of the explosives magazine itself was negligible."

Las Cruces Sun News, July 16, 1945

The Trinity test explosion was much larger than expected, and people noticed. They called their local newspapers demanding an explanation, and Laurence’s press release fed them a cover story explaining away the blast. The media ran with the story, including this New Mexico paper. “There was no loss of life or injury to anyone,” the paper said, repeating the press release verbatim.

The Boston Daily Globe, August 7, 1945

In the first 24 hours after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the War Department disseminated a number of ready-made articles authored by Laurence. Many newspapers didn’t question the official story. Here, The Boston Daily Globe reproduced Laurence’s triumphant account of the Trinity test in its entirety, as did many other news outlets.

The New York Times, August 7, 1945

The New York Times’ frontpage coverage of the atom bomb echoed President Truman’s statement that the bomb was dropped on an “important Japanese army base.” In truth, the bomb was aimed at Hiroshima city center for maximum psychological effect; the army base on the city’s outskirts escaped much damage.

Daily Express, September 5, 1945

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, was determined to keep American reporters away from both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. MacArthur enacted a strict press code that required American journalists to file their articles through his office and censored any stories that contained true on-the-ground reports. As a result, the first published account of radiation sickness from Hiroshima was written by Australian reporter Wilfred Burchett and didn’t reach American media.

Daily Telegraph, September 6, 1945

Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett continued to report on the nuclear fallout, not sparing readers from its human effects. “Their flesh began rotting away from their bones, and in every case the victim died,” he wrote, in a story that appeared in the UK’s Daily Telegraph. “Nearly every scientist in Japan has visited the city to try to relieve the people’s sufferings, but they themselves became victims.” Burchett’s reporting brought the truth to an international audience even as American media stayed silent about the bombs’ impact.

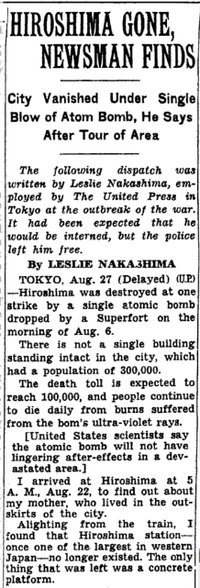

Nevada State Journal, August 31, 1945

Japanese American journalist Leslie Nakashima wrote an eyewitness report of Hiroshima for the United Press, an international news agency. Some U.S. papers carried that story, but in highly censored or editorialized forms. Nakashima’s piece ran here in the Nevada State Journal, but an editor’s note early in the story adds that “U.S. scientists say the atomic bomb will not have lingering after-effects in a devastated area.”

New York Times, August 31, 1945

Here is how Nakashima’s story appeared in the New York Times, highly edited and buried several pages into the newspaper.

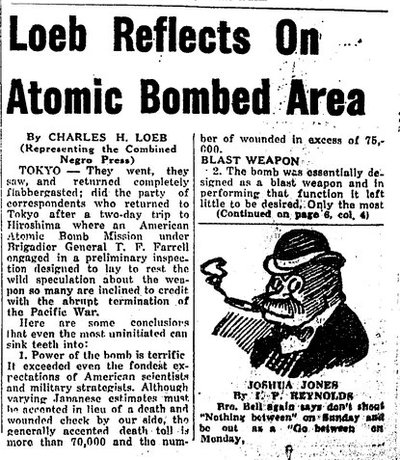

Atlanta Daily World, October 5, 1945

One of the earliest U.S. articles to acknowledge radiation effects, by journalist Charles Loeb, was published first in the Black press. “They went, they saw, and returned completely flabbergasted,” Loeb wrote of the journalists who were finally ushered into Hiroshima on a chaperoned visit.

The New Yorker, August 31, 1946

New Yorker Journalist John Hersey’s groundbreaking article about Hiroshima, published for the bomb’s one-year anniversary, was dedicated to survivors’ stories, breaking through a year of censorship and official spin. Taking up an entire issue of the magazine, this marked the first major crack in the U.S. government’s narrative. “The crux of the matter,” Hershey wrote, “is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good might result?”

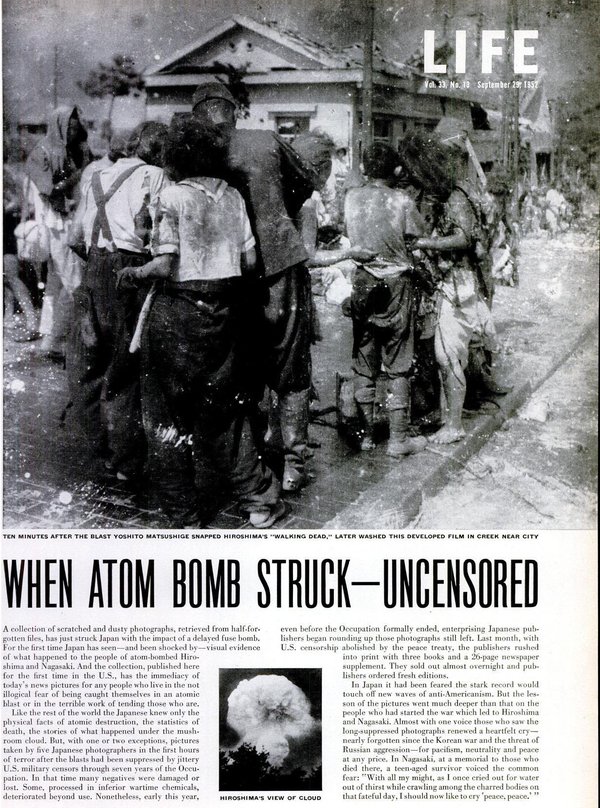

LIFE Magazine, September 29, 1952

After years of suppression, LIFE published photographer Yoshito Matsushige’s haunting on-the-ground images in Hiroshima, the only photographs taken in the bombing’s immediate aftermath. Americans were finally able to somewhat see the human cost beneath the mushroom cloud. See his photographs in the full documentary, Bombshell.