“Kissinger” – Part One

ARCHIVAL

WALTER CRONKITE: President-Elect Nixon today named Dr. Henry Kissinger, the German-born Harvard professor, as his White House policy advisor on defense and foreign affairs.

ROGER MORRIS, NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL STAFFER: In 1968, when Henry Kissinger was named National Security Advisor, he was not at all well-known, certainly not as famous or celebrated as he would become.

ARCHIVAL

HENRY KISSINGER: I enthusiastically accept this assignment and I shall serve the President-Elect with all my energy and dedication.

SAM HOSKINSON, NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL STAFFER: There was something about him that was different, like the way he talked.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I have tried to avoid labels like hard and soft.

HOSKINSON: Here’s this Harvard professor, kind of a nerd, a nerdish guy, that became one of the most powerful men in the world.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I believe that what America does is of great consequence to the peace of the world and to the progress of humanity.

NIALL FERGUSON, HISTORIAN: He entered the realm of power and bestrode it as a geopolitical colossus.

BEN RHODES, FMR. DEPUTY NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISOR: He had enormous power, more power than any unelected official probably in the history of this country.

JEREMI SURI, HISTORIAN: And the moments he lashes out most are the moments he feels powerless.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: We are not talking about an attack on a neutral country.

BARBARA KEYS, HISTORIAN: The secrecy, lying, the denial of reality, those are all Kissingerian.

GREG GRANDIN, HISTORIAN: I don’t think he had much concern for the human costs of his actions.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: The question about the relationship of morality to foreign policy is a very complex one.

RICHARD HAASS, DIPLOMAT: I don’t think he’d deny that he overlooked certain human rights, he would just say, “there were other factors at stake.”

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: Sometimes statesmen have to choose among evils.

ROHAM ALVANDI, HISTORIAN: He wasn’t trying to win a popularity contest, he was trying to implement his ideas.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I believe we have an obligation to prevent the totalitarians from taking over the world by force.

PETER KORNBLUH, NATIONAL SECURITY ARCHIVE: Yes, he was brilliant. But in the end his legacy is about the number of people, and we’re talking hundreds of thousands, have died because of the arrogance of his policies.

FERGUSON: Nobody, before or since, has played such an important role in American foreign policy. We've had to recognize it's Henry Kissinger's world.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Tonight, Henry Kissinger talks about war and peace and his decisions at the height of his powers.

TITLE CARD: KISSINGER

PART 1: The Necessity of Power

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I was brought up in a totalitarian society, and therefore I had perhaps a better sense for the fragility of institutions, and for the potential evil that can break forth when restraints disappear.

FERGUSON: One has to remember that Henry Kissinger was born at a time when Germany was in a state of near revolutionary upheaval.

ALVANDI: In the 1920s, the economic crisis of hyperinflation that engulfs Weimar Germany, combined with the sense of grievance about the terms imposed on Germany after the First World War, generates the rise of a very vicious right-wing fascist movement, for whom Jews are the scapegoats. And the Kissingers, like a lot of German Jews had no sense of what was going to come for them in the 1930s.

ARCHIVAL

NAZI CROWD: Heil! Heil! Heil!

CARD: A Lost World

FERGUSON: Fürth in Bavaria had a significant Jewish population in the 1920s. Heinz Kissinger is born into one of the Orthodox families in Fürth, and grows up in a middle-class Jewish household. Heinz had two distinctive features: a brilliant mind, an indefatigable energy. Well if he got the brilliance from his father Louis, he got that endless energy from his mother, Paula.

SURI: Their Jewishness is serious – they're Orthodox. They're kosher. But in terms of their work and education lives, they see themselves integrated in German culture.

ANGUS REILLY, WRITER: Despite Kissinger’s later reputation, he’s not a particularly studious child. His mother complains that him and Walter are always running away from kindergarten.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

PAULA KISSINGER: Henry was born in ‘23 and Walter was born in ‘24. And they were terribly naughty and hard to handle.

DAVID KISSINGER, SON OF HENRY KISSINGER: He always said that he was a gregarious, fairly frivolous young man. And he maintained that he had a rather happy childhood.

FERGUSON: But the childhood came to an abrupt end with the rise of the Nazis.

ALVANDI: The Jewish community, which had been very well integrated into a fairly liberal and cultured Germany, suddenly finds itself the target of the wrath of the German right. For people like the Kissingers, this is a shock. There is a deep reluctance to believe the depth that this depravity can reach.

THOMAS SCHWARTZ, HISTORIAN: Kissinger remembered that when he and his brother would take their bicycles to go visit their grandfather, he would see the signs saying “Jews are not wanted here.” And Kissinger commented later about how everything seemed changed.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: I was prohibited to go to German schools. All the German people with whom my parents associated more or less cut off all contact with us.

ARCHIVAL

HERMANN GÖRING: A citizen of the Reich can only be a person of German or related blood.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: A policy of segregation for Jewish people was created and my father lost his job.

ARCHIVAL

NAZI CROWD: Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!

REILLY: Because Louis is an employee of the German state he is sacked and it devastates him. He got so much fulfillment out of his job as a teacher, and then suddenly he was bereft, he was lost, and he withdraws in on himself, and Kissinger feels distanced from his father.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: My father was a teacher and not a practical man, and he was sort of paralyzed in the face of the evil the Nazis represented.

ALVANDI: I can't imagine how destabilizing and terrifying it must have been for Kissinger to see that world around him that he so admired turning against him, that a society that was seemingly so civilized, so refined could descend into this kind of madness.

REILLY: There is a sense of a lost world that he'll never be able to return to. His childhood featured that profound loss of innocence, of joy and prosperity and ease.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: That was a wrench in my life that had a deep impact on me. It was the possibility that what had given you security could disintegrate.

ARCHIVAL

NAZI CROWD: Heil Fuhrer!

CARD: Nuremberg 1937

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: My mother was extremely practical and she decided that they should leave Germany. My father didn’t object.

P. KISSINGER: I was mainly afraid for the children. You saw that they were so isolated.

REILLY: In 1938, they leave. They take a couple of trunks with a few precious personal items, and then they have to leave everything behind.

FERGUSON: The Kissingers left in the nick of time, just weeks before the huge pogrom that we know as Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass.

REILLY: Mobs across Germany torched Jewish homes, they attacked Jewish people in the streets, they destroy synagogues. And in Fürth they drag as many Jews as they can to the town center. And they have to stand there and watch as the synagogue burns to the ground.

ALVANDI: The Kissingers are not spared the Holocaust in Germany. Kissinger loses thirteen members of his family in the Holocaust, and I think for Kissinger, it generated a deep pessimism about the idea that norms and rules are gonna protect you. Really, at the end of the day, the only thing that's gonna protect you is power.

CARD: Frankfurt on the Hudson

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: There was this cousin of mine who brought us here, and when we arrived by boat, as we came down the gangplank, he said, “your name now is Henry.”

CARD: WASHINGTON HEIGHTS | 1938

REILLY: The Kissingers settle in Washington Heights, which has a large community of German Jews. It's known as Frankfurt on the Hudson, or the fourth Reich. And they try and build a life that to an extent mirrors the one they've left.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: We didn't have any money. My brother and I slept in the living room. We had no privacy. But I did not feel that I was suffering.

FERGUSON: The challenge, of course, was to arrive in the United States in the Depression. That was why Henry Kissinger had to get a job.

D. KISSINGER: He worked in a shaving brush factory. He went to night school. He didn't have the opportunity to have a lot of fun, but he also seems to have felt an enormous sense of relief because he didn't have to cross the street to get away from kids who would beat him up.

FERGUSON: He starts to study and he immerses himself in the very vital life of New York City in the late 1930s.

D. KISSINGER: I think he fell in love with New York, very quickly. He fell in love with baseball. And he fell in love with my mother.

My mother's name is Annalise Cohen. They very quickly started dating, and it became a very sweet, and dedicated relationship. They had been through the same kind of trauma, but they shared a desire to turn the disaster that they had experienced into a life of meaning.

But I think it was the army that truly gave him the confidence that he could be a true American.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: The attack was carried out by Jap torpedo planes together with dive bombers.

REILLY: Kissinger is at a football game, comes out and sees that newspaper boy with the headline saying “Pearl Harbor Attacks.” And he doesn't have any idea where Pearl Harbor is.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Immediate response from the Youth of America. Army, Navy, and Marine recruiting stations close to overflowing.

FERGUSON: Most teenagers pretty quickly figured out that they might not be interested in war, but war was likely gonna be interested in them.

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT: The second number which has just been drawn is 192.

MUSIC FROM IRVING BERLIN SONG: This is the army, Mr. Greene!

FERGUSON: The US army was not a tremendously discerning institution in the early phase of World War II. It took its young men from wherever it could and from wherever they’d come from.

REILLY: He is drafted in 1943 and he's sent to a rifle company in the 84th Infantry Division of the rail splitters.

CARD: Camp Claiborne, Louisiana | 1944

FERGUSON: Initially, the young Henry Kissinger found himself in this extraordinary melting pot of young men in training camps that were spartan to put it mildly.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: I thought it was a tremendous experience. Not every minute of which I enjoyed, but I now think it was one of the most important experiences of my life.

I had never met any really native-born Americans, and these people from the Midwest were very tolerant and friendly, and I got to know America as a result of serving in the army.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: These are the men who served in the 84th Infantry Division, a division that distinguished itself in a series of critical engagements during World War II.

REILLY: Kissinger lands in France five months after D-Day in November, 1944, and someone clearly recognizes his linguistic talents, and he's put into the counterintelligence part of the 84th Infantry Division.

FERGUSON: It’s not long after D-Day that Kissinger finds himself in one of the great battles of the war in Europe, the Battle of the Bulge. The fighting was hard. The Germans put up stiff resistance, the casualties were high.

REILLY: The 84th is trapped in a Belgian town, Marche-en-Famenne, and Kissinger works in the courthouse with the general and other staff monitoring everything and helping to organize the defense of the town.

FERGUSON: It was especially dangerous for Kissinger because as a German Jew by birth, he risked execution if he were captured.

REILLY: After the Battle of the Bulge, the 84th Infantry Division heads towards the city of Hanover, where they come across the Ahlem concentration camp, and it is a horrendous place.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Out of a thousand Polish men brought here ten months prior to April 1945, only two hundred remained. Prisoners who could walk were removed before American troops entered Hanover. The others were left to starve and die.

REILLY: Horrified, they radioed to the headquarters, which is where Kissinger is, and he drives up. And they come into this camp and Kissinger is just staggered by it.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: When questioned, most of these men could not remember when they'd last eaten a decent meal. Many had been beaten and tortured so long, their minds had failed.

D. KISSINGER: My father described his experience, liberating the Ahlem concentration camp as something that words could not entirely communicate.

VOICEOVER – WORDS OF HENRY KISSINGER: As our Jeep traveled down the street, skeletons in striped suits lined the road. Cloth seemed to fall from the bodies. The heads were held up by a stick that once might have been a throat. Poles hang from the sides where arms should be. I see my friend enter one of the huts and come out with tears in his eyes. “Don't go in there. We had to kick them to tell the dead from the living.”

REILLY: To him, it always was the most horrendous thing that he'd ever seen.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: The victims relate the atrocity stories and photographs are made for further documentation of the horrors committed at the Hanover camp.

REILLY: The power of knowing that it could have been him in that camp. That stays with Henry Kissinger.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: The deaths continue even after the liberation of the camp. Some are too far gone when the Americans took over.

D. KISSINGER: It was an illustration for him that strength was an unavoidable facet of resisting evil. That the attempt to deal with evil through compromise sometimes was not enough.

REILLY: After the war, Kissinger writes to the mother of an old friend of his from Fürth who had survived a concentration camp, he writes to warn her of what her son will now be like.

VOICEOVER – WORDS OF HENRY KISSINGER I feel it necessary to write to you because I think a completely erroneous picture exists in the United States of the former inmates of the concentration camps.

REILLY: Kissinger writes, he has not only suffered, but he has lived in an anarchic world in which is survival of the fittest in which there is no order, there is no structure or sense of society.

VOICEOVER – WORDS OF HENRY KISSINGER Concentration camps were not only mills of death, they were also testing grounds.

REILLY: It's a warning that morality has its limits. And that this was about power and strength and survival, above all else.

VOICEOVER – WORDS OF HENRY KISSINGER The intellectuals, the idealists, the men of high morals had no chance. It was a necessity to follow through with a singleness of purpose, inconceivable to you sheltered people in the States.

ARCHIVAL

ARMY NARRATOR: The problem now is future peace. That is your job in Germany. You'll see ruins, you'll see flowers, you'll see some mighty pretty scenery. Don't let it fool you. You are in enemy country. Be alert, suspicious of everyone, take no chances.

FERGUSON: Germany in 1945 was in a state of collapse.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Proven war criminals must answer for their crimes.

FERGUSON: As a member of the counterintelligence corps, Kissinger had to find out who were the Nazis? So Kissinger went from fighting Germans to trying to understand them.

ARCHIVAL

ARMY FILM NARRATOR: Somewhere in this Germany are stormtroopers by the thousands out of sight, part of the mob, but still watching you and hating you. Trust none of them.

D. KISSINGER: At a very young age, my father was given enormous authority over an area around Hanover to apprehend high-ranking Nazis.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

KISSINGER: My job was to arrest all Nazis above a certain level. And at that time, of course, every German claimed that he hadn't been a Nazi.

REILLY: For someone so young, it's a lot of responsibility, and he carries out the job effectively.

FERGUSON: It’s a rather extraordinary thought that the young twenty-two, twenty-three year-old Henry Kissinger is in this position of power over the very people who had been murdering his relatives, the very people who had driven his family across the Atlantic.

ALVANDI: There's no vengeance in Kissinger. He is not searching for some kind of feeling of righteous vindication. He's not a black and white person. He lives in the gray area in between.

CARD: The Meaning of History

ARCHIVAL

HARVARD SONG: There, Harvard, thy sons to thy jubilee throng, and with blessings, surrender thee o’er.

REILLY: Kissinger enters Harvard on the GI Bill, alongside millions of other new college students who had served in the military. And Kissinger is determined to take his own experiences and hit the ground running.

FERGUSON: He was the proverbial young man in a hurry.

D. KISSINGER: He tried many different subjects. For a while, he was on track to be a chemistry professor. He also flirted with going to law school, but ultimately, his fascination with history and government prevailed.

ARCHIVAL

PROFESSOR IN CLASS: The old regime in France was tyrannical, oppressive and…

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: Insofar as one could learn anything in preparation for a high governmental position, I think a study of history is the best preparation.

SCHWARTZ: He was definitely someone who was determined to conquer academia through sheer hard work and labor, not someone who joined college activities, joined college clubs.

D. KISSINGER: He was very rigorous about just using all of his time for his studies.

ALVANDI: He is the guy who's in the library 24/7, squirreled away in his dorm, reading from dawn to dusk, and so most of his Harvard contemporaries barely remember him. He manages to sneak in a dog, and I think that's pretty much his only friend there, by all accounts.

REILLY: And then Kissinger writes his undergraduate thesis: “The Meaning of History.”

ALVANDI: “The Meaning of History.”

FERGUSON: “The Meaning of History.”

SCHWARTZ: Yes, the famous “Meaning of History.” An extraordinarily detailed and philosophical thesis, which grapples with the big questions of human life, human meaning, meaning of history.

FERGUSON: It was the longest senior thesis in Harvard history.

ALVANDI: It was so long that Harvard had to introduce a rule that dissertations had to be, you know, within a certain word limit.

REILLY: “The Meaning of History” is extraordinary, but undisciplined, unedited and confusing.

SCHWARTZ: I have read it. If you ask me if I understand it, I would bet, wanna punt that question, but it produces a summa cum laude degree and admission to the graduate program in government and history.

ALVANDI: He spends many many years at Harvard and he’s just this very frustrated young PhD graduate who is kind of trying to find a place for himself, so what he does is kind of invents a place for himself.

REILLY: He studies the policies of European statesmen after the fall of Napoleon, and their attempts to bring about order and stability. He does see it as an analogy for the world of the Cold War and of nuclear weapons, in which states have to balance against each other undergirded by a fear of what war is like.

FERGUSON: The central problem of the Cold War was like a kind of chess game. There were two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. All the rest of the world was a chessboard. All the other pieces could be moved about that chessboard. Diplomacy showed a way in which at least temporary peace could be achieved.

ALVANDI: It was not just accepting the world as it is, but understanding realities of power and manipulating power in order to achieve the ultimate goal, which was peace and stability.

REILLY: It's about building the right balance of power so that war is impossible. Victory is impossible, because then only through that would you prevent another war.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Machine guns chatter a song of death, and rockets hissed down with terrifying accuracy onto the Reds below.

CARD: Korea | 1950

SCHWARTZ: Shortly after his graduation, the Korean War breaks out. The Korean War is really the Pearl Harbor of the Cold War.

FERGUSON: It was the moment when Americans could no longer ignore Stalin's ambitions to expand communism beyond the Soviet Union.

ARCHIVAL

ARMY FILM: The Democratic peoples must fight. And continue to fight until the grim red shadow that surrounds the world is dispelled.

SURI: We have a rising Cold War that now has become a hot war. And I think what the Korean War does is it creates for the next fifty years in the United States, an axiom that if you ever give the Communists a little bit of space, they will seize it and seize more. And so the United States has to be ever ready, has to be prepared for apocalypse at any moment.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Today every state, every city and town, is within striking range of a determined enemy…

FAREED ZAKARIA, WRITER: It's difficult for us, today, to understand how scared people were in the ‘50s and early ‘60s about the prospects of nuclear war.

Remember, these were the most powerful weapons ever designed in the world. And every military technology, every weapon that had ever been produced in human history had been used—and nuclear weapons had been used, twice.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Even the pigeons take part as New York holds its biggest civil defense drill.

ZAKARIA: The US strategy, which was called massive retaliation, was that if the Soviets use a single nuclear weapon against an American interest, the United States will hurl hundreds of nuclear missiles all the way to Moscow.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Times Square waits, millions wonder: suppose it were real?

ZAKARIA: But if the Soviet Union did something in a second-tier European country, would we really sacrifice New York and Washington, by retaliating against them? Kissinger's thought was no, and everybody knows it.

FERGUSON: Kissinger understood that there was something absurd about a strategy which gave you a choice between capitulation or Armageddon. And it was also true that there must be some limited use for nuclear weapons.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: What is the role of nuclear weapons? What is the significance of conventional forces?

FERGUSON: He talked to the experts, picked their brains, and then wrote his own book and that book became Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. It was the book that made him famous.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Henry Kissinger.

NEWSCASTER: Henry Kissinger.

NEWSCASTER: Henry Kissinger is the author of the bestseller Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy.

REILLY: Kissinger is offering the possibly radical argument that the United States should be willing to use nuclear weapons in smaller wars.

ARCHIVAL

MIKE WALLACE: You think American strategy should be reevaluated to restore war as a usable instrument of policy?

KISSINGER: American strategy has to face the fact that it may be confronted with war, and that if Soviet aggression confronts us with war and we are unwilling to resist, it will mean the end of our freedom.

REILLY: It suddenly makes him a hugely important public intellectual. He gets invited on television, he can write op-eds in the New York Times. He is now recognized as an important person in the conversations about the Cold War.

ARCHIVAL

INTERVIEWER: Dr. Kissinger, do you believe it’s true that we have no coherent strategy?

KISSINGER: I have no doubt that our military services have a plan for every conceivable contingency. But I have the uneasy feeling that these plans are not the same in each service.

ALVANDI: He's a very ambitious person, but he's also ambitious for his ideas. He wants to have an impact on history. And he realizes that in order to do that, he must cultivate relationships with power. So he begins to use the sort of cachet and prestige of Harvard to build relationships for himself beyond university.

FERGUSON: Now, if you are a policy intellectual, you are pretty stupid if you don't get expert about what's gonna become the dominant, divisive, foreign policy issue of the later 1960s. And that is, the war in Vietnam.

CARD: The Golden Moment

CARD: Vietnam | 1965

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT LYNDON JOHNSON: We do not want an expanding struggle with consequences that no one can perceive. Nor will we bluster, or bully or flaunt our power. But we will not surrender and we will not retreat.

FERGUSON: The United States had been getting steadily more involved in Vietnam during the Kennedy administration, but it was under Lyndon Johnson, after Kennedy's assassination, that US involvement escalated and large numbers of US troops began to be committed.

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT JOHNSON: Retreat does not bring safety, and weakness does not bring peace.

FERGUSON: The escalation really dates from ‘65, and that's the year that Kissinger first visits Vietnam. Why did he go? Well, I think Kissinger was genuinely interested in the problem that was evolving in Vietnam.

JOHN NEGROPONTE, FOREIGN SERVICE OFFICER: I first heard of him when we were all called into the political counselor's office in the embassy in Saigon, and he told us Dr. Kissinger was coming soon and I was asked to take him up to the northern part of the country. And so we took him to some remote places in Vietnam.

I wouldn't say he was exactly fearless. I can tell you one phobia he absolutely had, and that was flying. I remember one time he walks up to the pilot, and he says, “good morning pilots.” He says, “can this plane really get over those mountains?” Henry was holding onto the curtains of that airplane for dear life.

FERGUSON: The reports that he wrote from that and later trips to Vietnam in the mid-sixties are extraordinary, because he understood very quickly why the United States effort to prop up South Vietnam was failing.

SCHWARTZ: He recognizes that the United States is likely not able to prevail in the amount of time that public opinion would be supportive of the war effort. And he, from a very early point, believes that the United States has to find some type of negotiated solution.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I concluded then that there was no way of winning the war in the manner in which it was being conducted. So I felt from that moment on that we had to find a negotiated way out. But I also felt that having committed that many forces we couldn’t simply walk away.

NEWSCASTER: Professor Henry A. Kissinger of Harvard. He’s been an advisor to the United States Government under four presidents and has recently returned from Vietnam.

BRITISH STUDENT: Professor Kissinger, I find American intervention in Vietnam as immoral as Nazi and Italian intervention in Spain before the last war. Why don’t you?

KISSINGER: I don’t find the intervention in Vietnam immoral because our purpose is to give the people of South Vietnam a free choice. The Nazi intervention was to deprive the people of a free choice. And I would have thought that people in Britain should know the difference between American motivations and Fascist motivations.

PRESIDENT JOHNSON: I bring with me the love of your families, and the affection of your friends. I bring with me also the gratitude of the nation that you serve so honorable, and so loyally, and so well.

FERGUSON: By 1968, what Kissinger had spotted in 1965 was becoming obvious even to President Lyndon Johnson. The war in Vietnam was proving extremely hard to win.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: Americans risk, and sometimes give, all that they have half a world away from home.

FERGUSON: In order to try to figure out a graceful exit from Southeast Asia, a negotiation had to happen.

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT JOHNSON: Good Evening, my fellow Americans. Tonight I want to speak to you of peace in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

ELIZABETH BECKER: Then, in 1968…

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT JOHNSON: I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your president.

BECKER: President Johnson declared he would not run for reelection. He was gonna devote himself to finding a solution, and he was coming close.

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: The diplomatic deadlock over a site for the peace talks was finally broken. The North Vietnamese had revealed a willingness to talk, but only on their terms.

NEWSCASTER: In Paris, politics and diplomacy eventually assembled all parties to try to find peace in Vietnam.

ROBERT BRIGHAM, HISTORIAN: The Johnson administration opened secret negotiations in Paris.

The American public wanted to win, but they wanted to get out. And the clock is ticking.

JOHN FARRELL, HISTORIAN: Kissinger saw that there was a chance to claim power, and he went to Paris in September and he heard over there that there may be this bombing halt coming. This was the golden moment to say, “if I don't walk through that door now, and Nixon gets elected, it's going to be four years, or eight years, and I'm gonna be a Harvard professor again. No matter how smart I am, this is my shot.”

And this was despite the fact that Kissinger and Nixon did not know each other, and Kissinger had said throughout that summer that Nixon would be a disaster if he got elected president.

FERGUSON: Henry Kissinger had steered clear of Richard Nixon throughout his career as a policy intellectual, declining invitations to meet with Nixon because he really had a pretty low opinion of Nixon.

GREG GRANDIN, HISTORIAN: But Kissinger quickly made contact with the Nixon campaign, and he passed on the status of the talks through his contact Richard Allen.

ARCHIVAL [AUDIO ONLY]

RICHARD ALLEN: Henry Kissinger volunteered information to us through a spy he had, a former student, that he had in the Paris Peace Talks. He called me from pay phones and we spoke in German. And he offloaded mostly every night what had happened that day in Paris.

FARRELL: So he sends two different messages to Nixon on two different days in September, saying, “There’s this bombing halt coming. I just want you to know, think about what your position is going to be.”

GRANDIN: Kissinger told the Nixon campaign, you know, “they’re getting closer to a deal.” And Nixon’s people told the South Vietnamese government that it would get better terms if Nixon was in the White House.

This was the moment in which that distance between self-interest and national interest, at least in his mind, collapsed into each other. From that point forward, there was no daylight between the interests of Henry Kissinger and the interests of the United States—at least in Henry Kissinger’s mind.

ARCHIVAL

PRESIDENT-ELECT NIXON: Having lost a close one eight years ago, and having won a close one this year I can say this: winning is a lot more fun.

FARRELL: After the election, Nixon invites Kissinger to come to the Pierre Hotel in New York City.

FERGUSON: The Henry Kissinger who goes to the Pierre Hotel after Richard Nixon’s election victory is a player but a bit player.

MORRIS: Nixon had a general disdain for academics but he wanted and needed a kind of authority that Henry gave him in academic terms.

FERGUSON: Kissinger had met Nixon just once before, and they have one of those awkward conversations which were Richard Nixon's signature dish. And that’s why Nixon’s decision to offer Kissinger the job of National Security Advisor came as such a surprise to Kissinger that he didn’t realize Nixon had offered him the job.

FARRELL: Nixon is just so awkward with people that he had neglected to actually make the offer. So Kissinger comes away from the meeting with Nixon and he gets a phone call from John Mitchell, who is the campaign manager, and Mitchell says,

FARRELL - AS JOHN MITCHELL (PHONE EFFECT): So how do you like the new job?

FARRELL: And Kissinger says…

FARRELL - AS KISSINGER (PHONE EFFECT): Well, what job? No job was actually offered.

FARRELL: And Mitchell goes…

FARRELL - AS JOHN MITCHELL (PHONE EFFECT): Oh, for Christ's sake, he messed it up again.

CARD: A Bizarre Marriage

ARCHIVAL

NEWSCASTER: President-Elect Nixon made his first major foreign policy appointment today. He named Harvard professor Henry Kissinger to be his Special Assistant for National Security Affairs.

NIXON: Dr. Kissinger is a man who is known to all people who are interested in foreign policy as perhaps one of the major scholars in America and the world today in this area.

ALVANDI: The relationship between Nixon and Kissinger is fascinating and it becomes a bizarre marriage.

SURI: There's a wariness they have of each other early on, but I think they each see quite a bit of themselves in the other.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: The President-Elect and I have had many extensive conversations over the past week.

FERGUSON: It quickly became clear to Nixon that Kissinger was an asset. First of all, he understood Nixon.

ARCHIVAL

KISSINGER: I enthusiastically accept this assignment, and I shall serve the President-Elect with all my energy and dedication.

FERGUSON: Kissinger got inside his head super quickly and very quickly began to understand how to talk to this lonely, difficult, mistrustful man.

ARCHIVAL

NIXON: Dr. Kissinger is keenly aware of the necessity not to set himself up as a wall between the President and the Secretary of State, or the Secretary of Defense.

ZAKARIA: Nixon wants to bring foreign policy into the White House. In this, he finds a perfect partner in Henry Kissinger. I don't think one could have expected this, but Kissinger turned out to be a very savvy bureaucratic player. He was very good at maneuvering and counter-maneuvering, and he liked the secrecy, as well.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Kissinger meets alone with the President every day sometimes for as long as an hour and a half.

GRANDIN: Nixon and Kissinger turned the National Security Council into basically the main hub of foreign policy.

MORRIS: I had joined the NSC under the Johnson administration. It was a very loosely run operation, very small. There were only eleven or twelve of us. That was not true at all under Kissinger.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: These are the senior people from his National Security Council staff of about forty persons.

MORRIS: Kissinger's NSC staff was a much more concentrated power structure than anything that we had seen before.

WINSTON LORD: Kissinger made very clear that he did not want yes men. He wanted candid advice. Disagreement, if necessary. Argue your case, if you lose the battle, then faithfully carry out the policy.

TONY LAKE: He enjoyed thinking and arguing issues through.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: Find out whether it's possible on Thursday and then we'll make it depend on the other thing.

LAKE: I think he enjoyed having a few of us, maybe not too many, but a few of us who did not agree with him or the President politically. And I suspect he liked it because he won every argument, in part because he was very smart, and in part because–let me see, oh yes, I worked for him.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Kissinger admits to being a perfectionist, not an easy man to work for. He hires people…

HOSKINSON: He was a demanding perfectionist with his staff. Nothing could ever be right. There was also the joke that if Henry didn't yell at you, he didn't love you.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: He speaks of his staff with pride and a kind of affection. They call him Henry and regard him too with warmth, salted with a degree of apprehension, for he has a sharp temper.

MORRIS: We were graded. We were told we had done a B-plus or maybe an A-minus if we were really lucky, but always, of course, you had to go back because the only real A was Henry's own rendition.

LORD: Kissinger, he stretched my patience. He stretched my nerves.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: Will this meeting take very long?

ARC NEWSCASTEER SOT: He is regularly late to meetings. His staff despairs good-naturedly of that.

LORD: I would quit about once a week. He was a mentor. And a tormentor.

MORRIS: We worked murderous hours. We were often seven in the morning till eight or nine at night. And, uh, it took a toll on families. It took a toll on our physical stamina. But Kissinger demanded to be the guiding light, the north star, of the Nixon foreign policy, and that meant the policy in Vietnam.

CARD - Chapter Head: How To Get Out

Vietnam | 1969

ZAKARIA: Kissinger and Nixon enter the White House at a time when the United States is in a very, very difficult place in Vietnam.

LORD: In 1969, tens of thousands of Americans had already been lost. We were losing about two hundred a day. We were heading toward 535,000 troops in Vietnam. It was a hellish situation.

ARC NIXON SOT: We inherited a nightmare. It was shaking our domestic stability. It was the consuming concern of the intellectual community. We made up our mind in the very beginning that we were going to try to disengage from Vietnam.

MORRIS: That the war should end was unquestioned. The question was how? The question was when? The question was under what circumstances? With what honor or sense of honor?

ARC NIXON SOT: I want to end this war. The American people want to end this war. The people of South Vietnam want to end this war.

MORRIS: Very soon, the enormous sentiment against the war that had haunted and driven Lyndon Johnson out of power was going to be turned on Richard Nixon. They knew that.

ARC PROTESTORS SOT: What do we want? When do we get it? Now!

KEYS: What the Vietnam War did to many Americans was shake their faith that their country was decent and honorable. Because it seemed like the United States was fighting a war in a distant country in an extremely brutal way using chemical weapons like napalm, destroying villages, massacring civilians.

MORRIS: And Nixon understood that you had to change course.

ARC REPORTER SOT: How are you doing Mr. President in your efforts to end the Vietnam War?

ARC NIXON SOT: Once the enemy recognizes that it is not going to win its objectives by waiting us out, then the enemy will negotiate and we will end this war before the end of 1970. That is the objective that we have.

LAKE: Nixon had to show that there is hope, there's light at the end of the tunnel, and we're going to get out. But with honor.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: To me, ending the Vietnam War had been the principal goal of Nixon’s first term, not only in order to bring peace but in order to end our domestic divisions. And I wanted to create the conditions which would unify the country again by having an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.

D. KISSINGER: Foremost in my father's mind was finding a way to end the Vietnam War without a collapse of America's influence in the world, without a betrayal of millions of people who had relied on us, whose lives hung in the balance.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Melvin Laird, Secretary of Defense, arrived in Saigon today for a firsthand look at the progress of Vietnamization which he said was irreversible.

BRIGHAM: The secret plan that Nixon had to end the war—that wasn't so secret, or really a plan—was “Vietnamization.”

CAROLYN EISENBERG: Vietnamization is the brainchild of Melvin Laird, the Secretary of Defense.

ARC DEFENSE SECRETARY MELVIN LAIRD SOT: You cannot guarantee the will and the desire of any country, but you can give them the tools to do the job.

EISENBERG: The basic idea is that we should begin a policy as quickly as we can of pouring money and training into the military in South Vietnam, and that they'll be able to replace American troops.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Twenty percent of these young men are farmers’ sons, out of the rice paddies and flying solo in a matter of weeks. And that's what the three hundred South Vietnamese are doing here, learning to fly choppers for combat.

LORD: So over a period of time we felt that we could gradually withdraw American troops, which would maintain domestic support at home, and buy time for the other prong, which was secret negotiations.

CARD: Paris | 1969

LORD: The fact is that there were some public exchanges in Paris, but they were essentially propaganda battles, but the real negotiations were secret.

ARC REPORTER SOT: Avez-vous parlé de Vietnam?

ARC KISSINGER SOT: I won’t discuss any of the subjects…

LORD: Here’s the way it would work: we had to make a cover, pretending we’re still in Washington. So I would leave the office and say to my compatriots, I'm going to take the weekend off. And then I would join Kissinger. We fly into the middle of France. And we were met by a military attache who would sneak us into a safe house. In the safe house, we used code names so that the housekeeper wouldn't know who we were.

LAKE: I was “Major Larkin,” I remember. I couldn’t even be a lieutenant colonel, it was one humiliation after another.

If the negotiations were secret, then Henry would have much more flexibility in how to negotiate with them. So, first point was that they were secret not only from other governments, but from the State Department and the rest of the American government.

NEGROPONTE: We cut the State Department out of an awful lot of stuff and it was Henry versus them, and he just didn't want them to be involved or get any credit.

SCHWARTZ: Kissinger always feared, to a certain extent, that the State Department could undermine his control of foreign policy. And he made it a point of his role as National Security Advisor to try to gather in the authority of foreign policy to himself.

ALVANDI: And this gave Kissinger just tremendous power because really he was the only person that was fully in the loop.

SCHWARTZ: The North Vietnamese want the complete withdrawal of American forces. In effect, they want a type of American surrender and the North Vietnamese leaders were far more unified and determined to forcibly reunify their country at almost any cost than Nixon and Kissinger truly appreciated.

FERGUSON: Henry Kissinger always had considerable and usually quite well-placed faith in his ability to negotiate. So, his assumption was that if he could get in the room with a well-empowered North Vietnamese representative, he could find some room for maneuver. But they were also the hardest negotiations Kissinger ever experienced.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: It was our misfortune that Le Duc Tho’s assignment was to break the spirit of the American people for the war, and that he was engaged in a campaign of psychological warfare. So what he attempted to do to us was extremely painful.

ALVANDI: The North Vietnamese negotiators drive Kissinger insane because he tries to come up with every conceivable formula and variation of language that would be enough to achieve some kind of deal, but they just simply refuse.

LAKE: We would sit across the table and it would be Henry and an interpreter and me. And I would look at them very carefully, and they were not in the slightest cowed, as far as I could tell. But after all, they had defeated the French, they'd been holding off the Chinese for two thousand years, and it was hard to convince them.

FERGUSON: The problem was that his negotiating position was weakened by the fact that the US began withdrawing troops even before he began negotiating.

LAKE: We were going to San Clemente, the White House in California, and I wrote a memo to Kissinger saying, the problem here is that if we are Vietnamizing, then the first tranche of troops that come home are like salted peanuts. And the taste for further withdrawal of American forces is going to become overwhelming.

The North Vietnamese are not idiots, and they know that if they simply wait us out, then we're going to be withdrawing while they're not. So, we've got a problem, and therefore we need to cut the best deal we can now. Well, Henry took the conclusion off my memo, made it his own memo to Nixon, and then said that we have to threaten them all the more with measures of great force in order to make up for the weakness of our position on mutual withdrawal.

CARD - Chapter Head: Operation Menu

ARC GBH INTERVIEWER SOT: How would you characterize the Nixon administration’s policy towards Cambodia? The charges have been made that…

BECKER: What's important to know about Cambodia was that it was in the middle of the war. To the West was Thailand, which was the equivalent of the air base for the American war. To the North is Laos, and to the East, of course, is Vietnam. It's right in the middle, and it's neutral, run by a very charismatic leader named Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

ARC SIHANOUK SOT: I assure you we have given the Viet Cong no logistical or military aid of any kind.

SURI: Kissinger believes that Cambodia is a real problem for the United States in Vietnam, because even though the Cambodian king and others are trying to play neutral the North Vietnamese are sending supplies through Cambodia, that's just a fact.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: US bombing raids in North Vietnam force the creation of a primitive method for keeping supply lines open.

GRANDIN: Nixon and Kissinger came up with the idea, well, we’ll start bombing Cambodia.

FERGUSON: Kissinger thought if the North Vietnamese supply lines could be broken, if the flow of man and material could be disrupted, then the North Vietnamese would be greatly weakened.

LORD: The North Vietnamese were the ones who spread the war. They were sitting in Cambodia along the border for two years, coming across the border, killing Americans and South Vietnamese and returning to safe havens. And so the bombing was to not let them have safe havens.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: So we are not talking about an attack on a neutral country, we are talking about the attack on territory occupied by an enemy force, that is killing Americans from that territory.

GRANDIN: But the real reason for the bombing was to put into place what Nixon and Kissinger had come to call the “Madman Theory.” This was the idea that Nixon was so crazy, so unhinged that he might do anything. And it was supposed to project to North Vietnam a sense of fear and it was sort of gonna force them back to the bargaining table.

CARD: March 18 | 1969

SOPHAL EAR: So, Operation Menu is launched in which sorties secretly bomb the problematic area where the Ho Chi Minh trail is located.

MORRIS: Technically, there was no sanction for this in the U.S. Congress of any kind. And you're coming at a time when there's enormous pressure to wind down the war, enormous pressure to limit the war, not to extend it, not to expand it in any way.

EISENBERG: It was very clear to everybody, including Kissinger himself, that if the American public learned that they were bombing Cambodia, that there was going to be an explosion in the United States.

RICK SMITH: And so that's why they went secret. Because they knew damn well they couldn't get it any other way.

GRANDIN: Kissinger was intimately involved in choosing the bombing sites. He came up with basically a dual bookkeeping system in which bombs that were supposed to be dropped along the border within South Vietnam were actually dropped in Cambodia.

There's descriptions of him in an office within the basement of the White House with his maps picking out the bombing sites and working in this very clandestine manner.

This had the effect of really kind of pushing the White House deep into paranoia, into a sense that, that there were enemies all around.

ARC COLONEL RAY SITTON SOT: We were told that this is so sensitive that it must be done with the absolute minimum number of people being exposed to it. At one point Dr. Kissinger even suggested that why don't we do it using Skyspot radar? Even the crews won't know where they're dropping.

BRIGHAM: Mel Laird, Nixon's Secretary of Defense, was opposed to the secret bombing of Cambodia.

ARC LAIRD SOT: The manner in which they wanted to carry out that bombing, I thought would lead to trouble.

BRIGHAM: He thought there was no way that Congress wouldn't eventually find out.

ARC LAIRD SOT: And I told the National Security Council, the president, the presidential advisor for national security, and the Secretary of State that their proposal to keep it secret just would not work.

SURI: It was monumentally stupid to think that they could actually get away with doing this in secret. At some point, someone, some low-level Air Force official, would hand the books to a reporter—which is what happened.

EISENBERG: There's an article that appears in The New York Times by William Beecher. If you blinked, you might have missed it, but Kissinger and Nixon don't miss it. And that really sets Nixon and Kissinger off, enraged, like, how did he get that news? Who told him? And so that's the point at which they make a very fateful decision to start wiretapping people in the government, as well as wiretapping certain reporters.

SMITH: Nixon and Kissinger were paranoid about leaks. They wanted not only to control policy, but they wanted to control the narrative about policy. They wanted to decide when the public could find out, when the Congress could find out, when other members of the administration could find out.

SCHWARTZ: Kissinger had brought to Washington a large number of officials in his National Security Council staff who were known to politically lean more toward the Democrats. And this immediately raised the suspicion that they leaked this in order to undermine the policy of the administration.

SMITH: Kissinger was convinced there were people in his own staff, Mort Halperin, Tony Lake, Roger Morris, you name it, that were deliberately undermining their policy, that if they had an argument behind closed doors, that these guys were going public with it.

ARC NIXON SOT: That actually was a major subject for discussion, but uh..

SMITH: Nixon and Kissinger were both conspiratorial themselves, and if you're conspiratorial yourself, you tend to suspect everybody else of being conspiratorial, too.

SARAH SNYDER: I do think that Nixon and Kissinger, and I think it's important to think about them together, they fed on one another's paranoia, they fed on one another's need for secrecy, and they saw enemies in a very stark light. And so there was always a, sort of, us versus them.

LAKE: I was on vacation on Martha's Vineyard when Seymour Hersh called me and he said, “I'm running a story tomorrow that your phone was tapped. And they'd been listening to your telephone.” And I was really pissed. And I threw rocks at seagulls for a while.

SMITH: I don’t find out the wiretaps for four years, but my home was wiretapped, my family was wiretapped. The kids' conversations, my wife's conversations with her mother.

I've got the wiretapped logs now. “Neighbor talks to Mrs. Smith. Mrs. Smith said they would be leaving in 10 minutes for the weekend, destination not given, and wanted the neighbor to hold the papers for her. Mrs. Smith calls Hazel, the maid, and asks if she is coming over tomorrow. Hazel said she would be there.”

This is outrageous. I mean, what is the government doing? Listening to our phone calls and, even if they were looking for national security, not having the decency and the smarts to say, “We don't need this.” Unless they thought maybe we were passing secret signals to the neighbor…or Hazel.

EISENBERG: It's a fateful decision to wiretap because it begins a policy of distrust of your own people. You know, even if they're your friends, even if the people on your staff came on your staff, as many did for Kissinger, because they think that Henry Kissinger is going to bring peace and they’re there to help, they’re there to pitch in and to make that happen. And now, he is gonna start treating them like they’re enemies. And when that happens, sort of the level of paranoia begins to grow exponentially.

MORTON HALPERIN: There was secrecy, subterfuge, and confusion, and you learned that Kissinger's word could not be trusted. Whatever he told you, you knew something else was going on. He played off everybody against each other.

LAKE: The truth, as my Victorian grandmother used to say, was not always in him.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: Nice to see you.

LAKE: You could tell when the eyebrows would come together and he'd be like this, and he was being, perhaps, a little devious. But was very effective, mostly because of how smart he was, and because he had absolute certainty in his views.

HOSKINSON: He sought celebrity status, and he got celebrity status. There was something about him that was different.

CARD - Chapter Head: Secret Swinger

SALLY QUINN: The first time I met Henry Kissinger was at a party for Gloria Steinem, and about halfway through the dinner, I looked up and saw this little guy standing alone in a corner. So, I knew who he was, because I’d seen his picture, so I walked over to him, and I said, “Dr. Kissinger, how are you? I'm Sally Quinn from the Washington Post.” And I said, “why are you hiding over here in the corner?” And he looked at me, he said, “well, I'm really a secret swinger.”

ARC KISSINGER SOT: I said, I’m too busy to do any public swinging, and I don’t want you to think I don’t do any swinging, so why don’t you just assume I’m a secret swinger?

QUINN: The next day, he was inundated with calls from movie stars.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Kissinger is cutting quite a swath on Washington's social scene. He likes to spend well-publicized evenings in the company of such ladies as Jill St. John or Shirley MacLaine, who add luster to his image as the playboy of the Western wing.

QUINN: He was at Sans Souci Restaurant every night, every lunch, with some babe. It was incredible. He became this sex symbol in Washington.

FERGUSON: Others watched in bewilderment, trying to work out why this somewhat portly, overweight, bespectacled Harvard professor with a strong German accent could possibly be appealing to actresses.

ARC NIXON TAPE SOT: Where the hell do you think Kissinger was over the weekend when I was trying to call him?

ARC AIDE ROSE MARY WOODS TAPE SOT: Probably out with some babe.

D. KISSINGER: Why did he encourage the secret swinger reputation? I think he truly was just having fun.

I mean, you know, when Marlo Thomas, and Candice Bergen, are interested in going on a date with you, and you're a 46-year-old single man, who wouldn't?

QUINN: Well, listen, I was not in the bedroom with them, but I don't think that it was real romance. But then, he met Nancy, and they were inseparable from then on.

D. KISSINGER: She's a very brilliant, warm, and charismatic person, very confident in her own right, and her energy, her ability to live a big life, matched his. And she also doesn't lack for self-confidence. So, they just made for a very fulfilling pair. Nancy was the love of his life.

You know, my parents divorced in 1962, shortly after my birth, and he had met Nancy in 1968, I think he was ready to marry her from the moment they met. So, all these other detours were really just that.

FERGUSON: The reality was Henry Kissinger was more a workaholic and a control freak than he was a secret swinger. But Kissinger understood that this gave him not only stardom, but more importantly, some real influence. Being popular with the journalists can matter a lot, particularly when, as invariably happens, Washington politics turns nasty.

KEYS: Kissinger was a master manipulator of the press. This was at a time when diplomatic correspondents needed official sources of information, and Kissinger knew how to feed information to them, pretend to share secrets, flatter them.

MORRIS: He lied to them. He deceived them. He rewarded them. He paid attention to them ceaselessly. He curried the press as no foreign policy figure before him.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: When he signed on Henry Kissinger, the President had no idea how effective he would turn out to be with the press corps.

FERGUSON: His backgrounders, the background briefings, became the most popular events for the Washington press corps that there had been in years.

ARC REPORTER SOT: How do you like the reporting on the backgrounders?

ARC KISSINGER SOT: I like the way my anonymity is maintained.

HEDRICK SMITH: Kissinger was a charmer, and he knew how to turn on the charm.

QUINN: But Henry was always using everybody. That was his thing. That's what he did. So, of course, he was using the press. I mean, he was very cynical about the press. I mean, there are plenty of people in Washington who use people all the time. But Henry took it to such another level of expertise.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: You can’t come back there with us…

QUINN: So when you’re with Henry Kissinger you always had to weigh two things. Your own morals, values, and ethics, and the fact that there's a really brilliant guy who was fun to be around, had a good sense of humor.

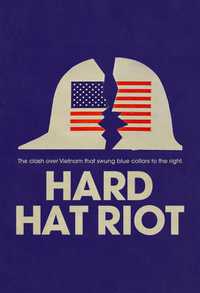

CARD - Chapter Head: The Silent Majority

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: On October 15, the first moratorium against the war turned out huge crowds in cities all across the nation.

SCHWARTZ: In 1969, there are massive demonstrations throughout the United States calling for an end to the war in Vietnam.

ARC PROTESTORS SOT: [chanting]

MORRIS: We were seeing those protests from the outside and the inside. Tony Lake and I had at one point stood outside on the south lawn of the White House and watched our wives and children demonstrating down Pennsylvania Avenue against the war.

ARC PROTESTORS SOT: Peace now, peace now!

LAKE: I can remember in the old Executive Office Building when I went up to the fifth or sixth floor, there were American troops sitting there with their backs to the walls and weapons in case the White House was attacked by the demonstrations outside. And I agreed with the demonstrators, but there I was.

SCHWARTZ: This has an enormous effect on Nixon, who does not want to admit it has an effect. What he does do in response is give the Silent Majority speech.

ARC NIXON SOT: Good evening, my fellow Americans. Tonight I want to talk to you on a subject of deep concern to all Americans and to many people in all parts of the world, the war in Vietnam.

FERGUSON: He has the kind of epiphany that everybody else has missed. If there is an educated minority implacably opposed to the war, doesn't that mean that there's a majority that doesn't feel that way?

ARC NIXON SOT: To you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support. I pledged in my campaign for the presidency to end the war in a way that we could win the peace.

FERGUSON: Nixon had his own innate disabilities as a politician. What he also had though was this ability to read the public and to sense what the moment called for.

ARC NIXON SOT: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Public reaction to the address was prompt, and some of those regarded as a silent majority broke their silence.

FERGUSON: He’s deluged with positive feedback to that speech. And it helped him in the polls, which he, of course, obsessively tracked. And it helped him in the kind of feedback that he got from telegrams and calls to the White House.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: The White House says it received thousands of letters and postcards, the vast majority supporting the President on Vietnam. In addition…

FERGUSON: It gave him time. It gave him the time he desperately needed to find some way out. And Kissinger had a plan.

CARD: Anything That Moves

KHATHARYA UM: The bombing campaign in Cambodia was a secret maybe to the Americans, but certainly not to the Cambodians.

EAR: Cambodia was never in the foreground of the Vietnam War. Cambodia’s suffering was not in the public eye, and therefore allowed to continue because nobody knew about it.

American B-52s ultimately dropped 539,000 tons of bombs. That is more than Japan during World War 2. The bombing eviscerates the country and two million people end up in Phnom Penh as basically internally displaced persons.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Some families manage to cling together. Somehow they survive and find a sort of peace.

EISENBERG: The secret bombing of Cambodia sets in motion a set of events which result in the overthrow of Prince Sihanouk, and almost within a year a relatively stable place has been turned into a hellhole.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: We could not permit the Communists to act in Cambodia with total impunity, which they had occupied before we did anything.

EISENBERG: The situation that is confronting both Nixon and Kissinger in April of 1970 was that Cambodia was disintegrating politically.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Many children still go to school, but many others carry guns. The war in Cambodia touches everyone and knows no age limits.

EISENBERG: What they were now confronting was not only are you going to have Communist troops right on the border of South Vietnam, but the whole country is going to go Communist, and then any possibility of an acceptable deal in South Vietnam, you know, would really begin to evaporate.

FERGUSON: Kissinger argued that there was an opportunity here decisively to impact the course of the war. The case he made to Nixon and to others was air power has its limits. There's only so much you can do with a B-52. You need to go in on the ground.

MORRIS: He managed, I think, to make his view, Nixon's view, in a very skillful way, while leaving Nixon with the impression that Nixon had made the policy, that it was Nixon's brilliance and not Henry's.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: From CBS News in Washington, this special report.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States.

ARC NIXON SOT: Good evening, my fellow Americans.

CARD: APRIL 30, 1970

BECKER: President Nixon went on air. He stands in front of the map and he says, “We are going into Cambodia, and we are going to go after the North Vietnamese who they don't want in their country and sending North Vietnamese back to their country.”

ARC NIXON SOT: If North Vietnam also occupied this whole band in Cambodia, or the entire country, it would mean that South Vietnam was completely outflanked.

BRIGHAM: He explains, you know, there are North Vietnamese troops clearly inside of Cambodia, violating Cambodia's neutrality, and that those troops and supplies pose a direct threat to the United States.

ARC NIXON SOT: We will be patient in working for peace. We will be conciliatory at the conference table. But we will not be humiliated.

KISSINGER VOICEOVER TK: The President wants a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia. He doesn’t want to hear anything. It’s an order, it’s to be done. Anything that flies on anything that moves. You got that?

LAKE: In April of 1970, Kissinger called in me and Roger Morris and then three others, I believe. At the meeting, Kissinger said that we are going to go into Cambodia. And, what do you think? And then we argued that this was bad strategically because Cambodia is now in play, et cetera, and domestically, it’s going to be a firestorm of some sort.

MORRIS: I remember banging my fist on the desk to the point that some of the papers actually rose. So, I said, “if there's one goddamn trooper across that line, I'm out of here.” Because I felt it was just, it was the last straw of escalation. We were working very hard, night and day, literally, on a peace settlement. The notion that we would, at that point, escalate very decidedly with an armed invasion of American forces? No, I mean, I just, I thought it was intolerable.

LAKE: I bore the brunt of the argument, and at the end of it, Kissinger said, and I can still hear his voice, “well, Tony, I knew what you were going to say.” And I thought to myself, “I can leave now.” I can send him a subscription to the New Republic or something, and I can go. And afterwards I said to Roger, “okay, this is it, I’ve had it,” and he agreed. And so we wrote a joint letter to him, and handed it to Al Haig, and said “please give it to him on the day the invasion takes place.” Which he did—and Kissinger was not pleased.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: There are several thousand American troops moving into Cambodia tonight. The dimensions of the war have certainly widened.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: It’s certainly a gamble, both in terms of the reaction of the enemy, and the reaction of the American public.

FERGUSON: As usual, when the United States escalates, in any way, in the Vietnam War, the anti-war movement goes into action.

BRIGHAM: College campuses erupted.

BECKER: What in the hell were we doing invading Cambodia? Everybody was angry. They were waiting for peace. And Congress was furious because this was done without their consent. The student population went insane.

SCHWARTZ: It led to an explosion of unrest at universities across the country, leading to the tragic killing of students at Kent State.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: National Guardsmen opened fire with semi-automatic weapons.

EISENBERG: Suddenly you have the National Guard shooting at students, I mean this is absolutely stunning.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: After the shooting, one young man dipped a black flag of revolution in the blood and waved it about.

EISENBERG: You know and then you have thousands and thousands of students coming to Washington.

ARC CRONKITE SOT: Mr. Nixon bore heavily his decision to send US troops into Cambodia and the awesome explosive impact of that decision here at home.

BECKER: It’s hard to exaggerate the anger.

ARC NEWSCASTER SOT: A few of the demonstrators confronted a cordon of buses in Lafayette Square protecting the White House, and from the other side police eventually responded with tear gas.

ARC PROTESTOR SOT: It was a peaceful rally, peaceful until it was attacked in a vicious and brutal manner…

SCHWARTZ: Nixon came close to a nervous breakdown in the wake of Kent State.

ARC PROTESTOR SOT: This was the price we paid for opposing Nixon and his genocidal policies…

SCHWARTZ: And Kissinger felt himself surrounded by protesters in his office.

ARC PROTESTOR SOT: …over and over again in the blood of our young people.

SCHWARTZ: They certainly felt very much under siege.

ARC KISSINGER SOT: The biggest problem domestically was whether we could finally unite the country, in which those who wanted peace would have peace, and those who wanted honor could live with themselves.

MORRIS: I think Kissinger harbored the notion that he could somehow pull off what Nixon wanted, which was peace with honor.

But, I think the quest for an end with honor was really a prolongation of the senseless waste and casualties. That he did not pursue ending the war in Vietnam, as he might have, with all of his gifts; that he did not use his genius in that way, I think is his, his ultimate indictment.

Kissinger

Kissinger