What the O.J. Verdict & Its Aftermath Revealed About Race in America

On the 30th anniversary of a verdict that shook the U.S., this seminal documentary on the O.J. Simpson trial offers lasting insights.

October 1, 2025

Share

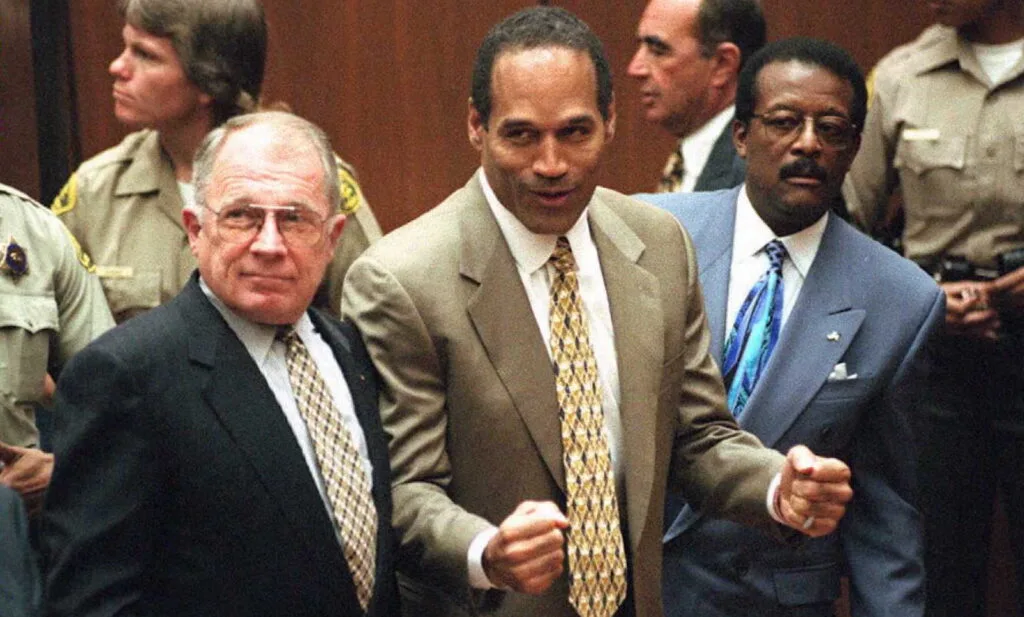

It had been more than a year since proceedings in what was being called “the trial of the century” began, and America was on edge.

Millions of households across the U.S. had tuned in to wall-to-wall coverage of onetime American icon O.J. Simpson’s trial for the brutal double murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman.

Then, on Oct. 3, 1995, came a televised verdict, watched by more than 150 million people, that shook the country along racial lines — sparking both consternation and celebration, and raising profound questions about the criminal justice system, fairness and America’s racial divide.

“Do I think that O.J. murdered those two people? Yes. Do I think he got off for it? Yes. Do I think he’s the first person to get away with murder in America? No,” Prof. Todd Boyd of the Univ. of Southern California told FRONTLINE in the acclaimed documentary The O.J. Verdict. “He got the same breaks that a rich white man would get, because he could buy them, and that’s the bottom line.”

Initially released in 2005, 10 years after the not-guilty verdict was handed down, The O.J. Verdict is now available to stream on FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel for the first time. It’s also available to watch at pbs.org/frontline and in the PBS App. Through extensive interviews with both the prosecution and defense teams, as well as journalists who covered the proceedings, the film offers an in-depth look at how the trial played out and the stark truths it revealed.

The documentary was directed by Ofra Bikel, an award-winning FRONTLINE filmmaker whose body of work exposed flaws in the U.S. criminal justice system and helped bring about the exonerations of at least 13 people.

“There was something about the O.J. case that got to the deepest parts of people,” Bikel, who died last year, said in an interview in 2005 when the film was released. She added, “People who usually believe in the system thought it could not have worked in this case because they did not agree with the verdict. It reached a point where they found the whole trial an unacceptable sham. And I don’t know what can explain it except race …”

Watch the Documentary

The O.J. Verdict

An in-depth look at how the O.J. Simpson trial played out and what it revealed about the United States

The trial, which took place in Los Angeles, came at a volatile time for race relations in the city. Just a few years earlier, a convenience shop clerk had been sentenced to a $500 fine, probation and community service for fatally shooting Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl. Then, the four Los Angeles Police Department officers who had been filmed beating Rodney King were acquitted of assault, sparking outrage and riots across the city.

Against the backdrop of that history, Simpson’s defense team highlighted examples of racism and alleged misconduct by the LAPD, including recorded uses of the N-word by the detective, Mark Fuhrman, who said he’d found a bloody glove on Simpson’s property. The team also stressed that the glove was obtained in a search conducted without a warrant, and made the case that the prosecution couldn’t be trusted.

It was a strategy that infuriated Ron Goldman’s father, Fred. When defense attorney Johnnie Cochran urged the jury to consider Fuhrman’s racism in making their decision, the distraught father cried at a press conference, “He suggests that racism ought to be the most important thing that any one of us ought to listen to in this court, that any one of us in this nation should be listening to, and it’s because of racism we should put aside all other thought, all other reason, and set his murdering client free.”

Attempting to prove Simpson’s guilt, the prosecution highlighted the infamous bloody glove and the former football star’s history of domestic abuse.

“Strategically, we led with the history of domestic violence, the history of O.J. Simpson battering Nicole Brown,” Simpson prosecution team member William Hodgman, then a Los Angeles deputy district attorney, said in the film. “And part of that strategy was to attempt to knock O.J. Simpson off that pedestal, that celebrated pedestal where so many people had placed him and had such a positive public image of him.”

The defense’s strategy was ultimately more successful with the jury, which found that the prosecution had failed to prove Simpson’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Bikel’s documentary explored how the not-guilty verdict served as something of a Rorschach test for the American public, with scenes of Black men and women celebrating victory in the streets, while outraged white Americans decried what they saw as a miscarriage of justice.

“This was taken personally by whites in America in a way that no other case ever affected them,” Simpson defense team member Alan Dershowitz said in the film. He added, “I got letters from people on every part of the political spectrum saying this was the worst verdict in American history, forgetting about the fact that they all grew up with the notion, ‘Better 10 guilty go free than one innocent be wrongly convicted.’ This case somehow became personal.”

It was personal for Black Americans, too. The late Prof. Charles Ogletree of Harvard Law School said in the documentary that the celebration of the verdict was “not in any way a reflection of lack of concern about these victims who were viciously murdered.” Rather, he said, it was in recognition of “the many Black men who had gone through that justice system, who didn’t have good lawyers, who found themselves going to jail, rather than going home.”

Simpson was held liable for the deaths of Brown Simpson and Goldman in 1997 in a civil suit their families filed. He would later be convicted of armed robbery in a separate incident and serve nine years in prison. He died in 2024.

On the 30th anniversary of the double-murder verdict, revisit Bikel’s documentary memorializing the heartache, confusion and tension it unleashed, and probing some of its lasting impact.

As Jeffrey Toobin, then of The New Yorker, said in the documentary, “The only reason that we will care about O.J. Simpson 10 years after, 20 years after, is what it told us about race in this country.”

The O.J. Verdict is now available to stream at pbs.org/frontline, in the PBS App, and on FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.