How a SC Riverkeeper’s Detective Work Reveals a Deeper Tale About the Carpet Industry’s PFAS Legacy

Congaree Riverkeeper Bill Stangler traced PFAS "forever chemicals" to a specific carpet plant on the Lower Saluda River in Irmo.

February 2, 2026

Share

1. A surprising result

One day in May 2022, Bill Stangler eased his green canoe into the cool current of the Lower Saluda River, a ribbon of water that springs from the depths of Lake Murray and is so cold that rainbow trout swim here even in Columbia’s sweatbox summers.

Stangler is the Congaree Riverkeeper, a watchdog for South Carolina’s largest Midland rivers, including the Lower Saluda. He carried water sample kits that day and made sure not to wear sunscreen and clothes that might contain PFAS chemicals.

At the time, Stangler only had a vague idea about PFAS. He knew they were called “forever chemicals” because they took decades or longer to naturally break down. He knew they were linked to serious health conditions, even in minuscule amounts. And he knew they were in everything from cosmetics to firefighting foam to nonstick cooking pans. But that was about it.

Then he’d gone to a conference where he’d learned that North Carolina’s Cape Fear River was a PFAS hotspot from factories that made the stuff. He told an expert at the conference: Good thing I don’t have any PFAS sources in my watershed.

“No, you do have them,” the guy answered. “You just don’t realize it yet.”

Back on the river, Stangler paddled closer toward Shaw Industries’ plant. The complex made nylon fibers and resins for carpets. It sprawled across 470 acres: pipes, stacks and beige warehouses barely visible behind a screen of trees.

Stangler chose this stretch of river because he’d read that carpet makers used PFAS to produce stain-resistant carpets. Muskrats swam by as he collected samples. He paddled back to the boat ramp. He sent the kits to a lab and waited.

Less than four months later, he found himself on a conference call with riverkeepers from all over the country. They’d also taken samples, and the results were in — “the big unveil,” Stangler said. The worst readings for one forever chemical was on North Carolina’s Cape Fear River — downstream from those PFAS factories. No surprise.

“Being the jerk that I am, I came off mute and said, ‘Number 1, way to go!’ ” Stangler recalled.

He’d spoken too soon. South Carolina’s Lower Saluda clocked in with the third worst reading of another type of PFAS. “I knew I had more work to do.”

That uh-oh moment would soon open a window into a much larger and deeper story: How one of the South’s most important industries wove itself into one of the world’s most pervasive pollution crises.

It’s a story about how leading U.S. carpet makers benefited from PFAS chemicals but also contaminated waterways near their plants. It’s about how state and federal regulators were slow to protect the public. And yet, it’s also about how Shaw Industries discovered clues in South Carolina that may help other companies deal with their tainted pasts.

It’s a tale rooted in thousands of pages of court documents, interviews in four states, environmental records and emails uncovered by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and a partnership of journalists across the South, including The Post and Courier, FRONTLINE (PBS), AL.com and The Associated Press. Many of these documents have not been made public until now.

For Stangler, it was a detective story that led to a lawsuit and a possible path in South Carolina toward reducing some of this pollution.

The story goes back generations and starts with one word, and it’s not carpet.

2. Dalton’s carpet barons

It’s bedspreads.

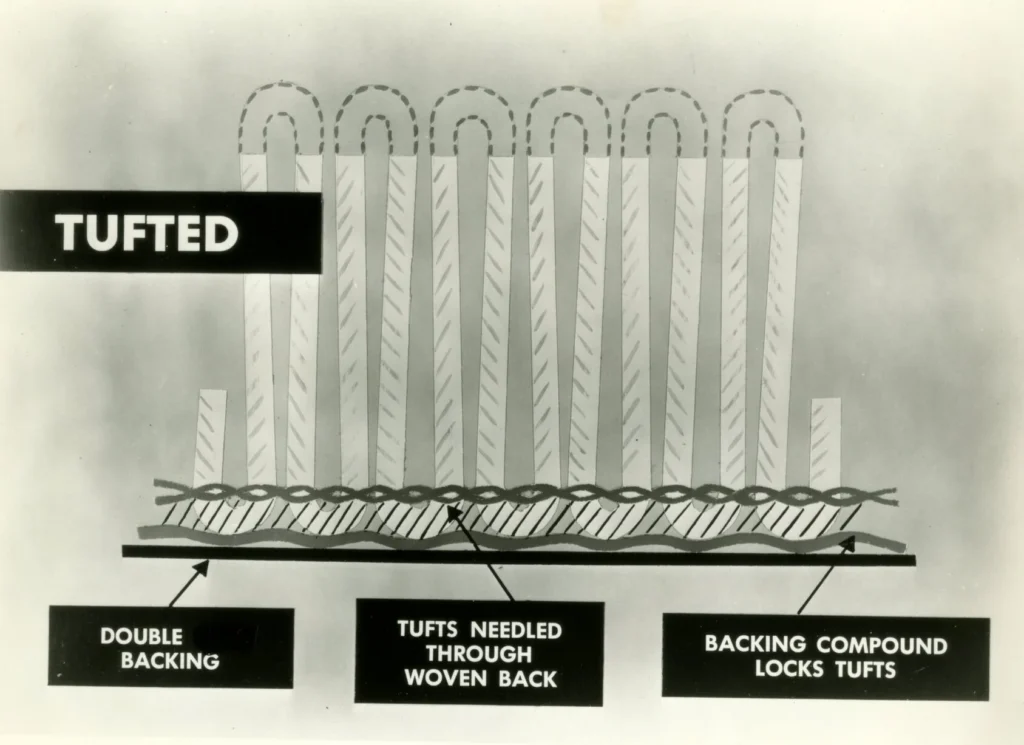

A teenager in Dalton, Ga., named Catherine Evans Whitener was said to have made a bedspread as a wedding gift for her brother roughly around the year 1900. Her work was creative: She stitched a series of yarn loops and then clipped them to make soft tufts in an intricate design. The effect created tufts with the texture of fur from a caterpillar.

The French word for caterpillar is chenille. Soon women across northern Georgia stitched “chenille spreads” at home. The women’s handiwork dried on clotheslines along a highway through Dalton. Peacocks were a popular design element and, over time, tourists nicknamed the highway “Peacock Alley” for the colorful peacock bedspreads hanging in the breeze.

By the 1930s, mechanization transformed this folk art into mass production. Entrepreneurs in Dalton adapted sewing machines to speed the tufting work. Tufted strands also created rugs with a soft and springy feel, and some tufting mills moved into carpet manufacturing.

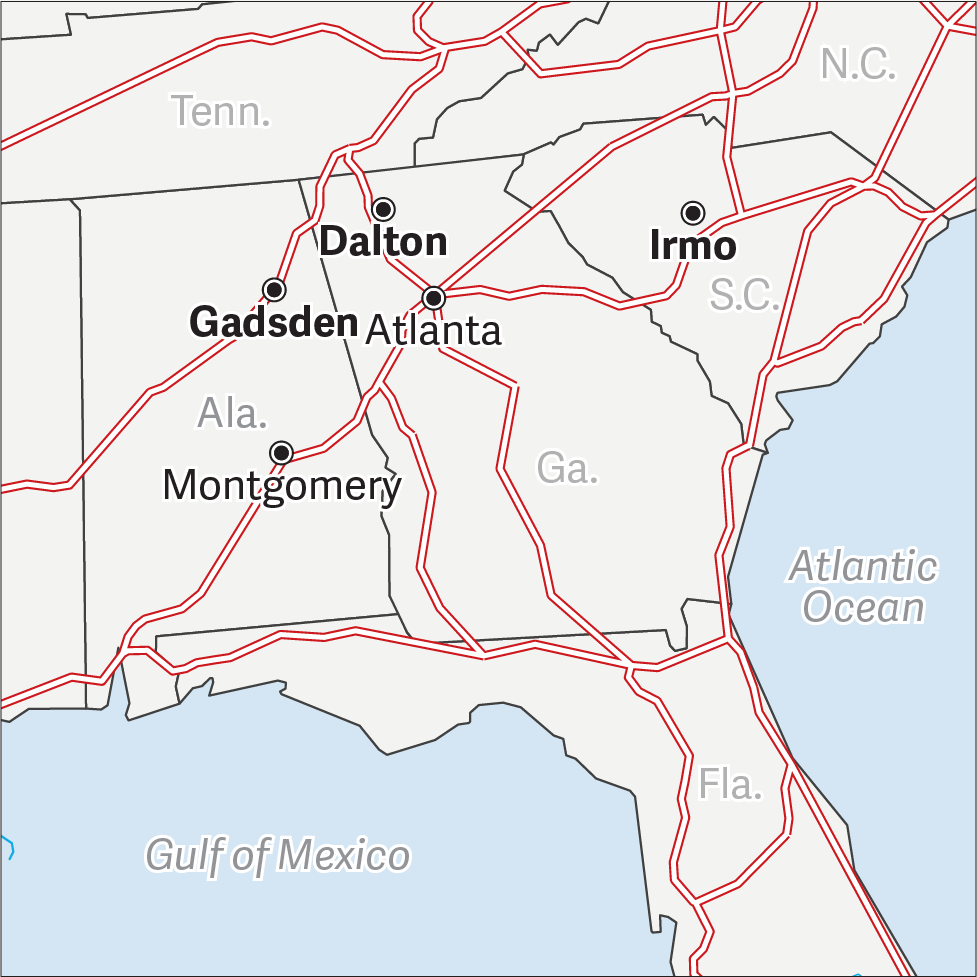

One of Dalton’s leading textile makers was Clarence Shaw’s Star Dye Company, which served the tufted bedspread trade in the 1940s and 1950s. His sons, Bob and Bud, later moved into carpet manufacturing and changed the name to Shaw Industries. By 1977, roughly 400 mills produced tufted carpet in America, most within 50 miles of Dalton, which became known as the “Carpet Capital of the World.”

So many carpet mills were in Dalton that it was known to snow blue from all the dye particles floating in the air. Employees worked ankle-deep in carpet dyes, and dyehouse spills turned rivers purple and killed fish. Rival executives were neighbors. Carpet company insiders sat on city council and the board of Dalton’s water system. “Everybody’s got lint in their hair,” a former resident told a reporter in 1987.

In 1995, the FBI and EPA raided Dalton Utilities’ offices. The Justice Department later charged the utility with falsifying wastewater reports, leading to a $6 million fine. Federal antitrust investigators also arrived in Dalton to take a hard look at the wall-to-wall carpet businesses. One price-fixing case yielded a guilty plea from an executive with Sunrise Carpet Industries, a one-year prison sentence and a $750,000 fine. A separate class action lawsuit also was filed against Dalton carpet manufacturers, which led to a $49.7 million settlement but no admission of wrongdoing. During this time, a federal judge said: “I don’t know another industry where the competitors are so (physically) close together.”

By 2000, Shaw Industries was a market leader but also bucking financial headwinds. Consumers moved away from carpet to hard flooring options. A recession hit, slowing sales. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway pounced, purchasing a majority stake for $2 billion. Buffett kept Shaw Industries’ longtime executives, including its silver-haired co-founder, Bob Shaw.

It was during this tumultuous period that another problem suddenly made headlines.

3. Early warnings

One May morning in 2000, Bob Shaw’s secretary had a television tuned to a news report. She phoned her boss: 3M Company was phasing out a certain PFAS in Scotchgard, the well-known water and stain blocker. In a press release, the EPA thanked 3M for “identifying this problem and coming forward voluntarily.”

Shaw was furious, according to a sworn deposition from Carey Mitchell, then Shaw’s technical services director. Shaw’s company was one of 3M’s largest customers. Scotchgard and DuPont’s Stainmaster helped create the modern carpet industry. The industry’s fortunes hung in the balance. Why hadn’t he been given a heads up?

Soon after, Shaw met with 3M executives in Dalton. “Bob Shaw walked over to the side and picked up a carpet sample,” Mitchell said in the deposition. Shaw “pointed to the Scotchgard logo and said, ‘That’s not a logo. That’s a target. And I got 15 million of these out in the marketplace. What am I supposed to do about that?’ ”

A top 3M executive reportedly answered: I guess you’ve got a problem.

Shaw “glared at him for a couple of minutes and threw the sample across the table at him and walked out,” Mitchell said.

3M’s announcement in 2000 may have caught Dalton’s carpet barons off guard. But the carpet industry already had warning signs that something about those PFAS chemicals wasn’t right.

***

As far back as the 1960s, 3M and DuPont had evidence that their miracle chemicals had a dark side, according to documents that later surfaced in lawsuits. One study in 1965 attributed an “epidemic of polymer-fume fever” to workers exposed to Teflon. In 1978, 3M tested PFAS on monkeys, but researchers stopped the experiment after 20 days because the monkeys died. In 1980, 3M’s medical director found high levels of PFAS in the blood of plant workers. During that time, DuPont had animal studies that showed PFAS damaged the liver and adrenal glands.

By the late 1990s, 3M had begun sharing internal findings with Shaw and Mohawk executives, but not the public, court records show. In one meeting, 3M revealed how their workers had PFAS chemicals in their blood. A Mohawk vice president seemed “somewhat uninterested and hurried,” a Shaw official recalled in a deposition. Shaw executives looked “concerned but quiet.” 3M also began inspecting Dalton’s mills under the guise of “industrial hygiene,” court records show. The visits revealed that carpet workers routinely were exposed to the chemicals. 3M urged Shaw executives to make sure workers didn’t eat sandwiches near the chemicals.

In 1999, a scientist at 3M named Richard Purdy resigned, calling a PFAS chemical in Scotchgard “the most insidious pollutant since PCB.”

In a letter to his bosses, Purdy wrote that his research showed a 100 percent probability that PFAS chemicals harmed sea mammals. He and his colleagues also found a type of PFAS in eaglets in remote areas, suggesting contamination was widespread. Forever chemicals were “more stable than many rocks,” he said. He warned that the chemicals 3M was considering as replacements were just as stable. He said 3M superiors told him not to write things down, and that the company waited too long to tell customers. “I felt guilty about this,” he wrote.

Purdy also sent his letter to the EPA. The long-held secrets about PFAS were out. Negotiations with the EPA led to 3M’s sudden announcement in 2000 that it would phase out the key PFAS in Scotchgard – and Bob Shaw’s outburst.

Now, the carpet industry had a big decision: The companies could stop using PFAS – and potentially lose the stain blocking that consumers expected.

Or they could switch to new PFAS chemicals, substitutes with tweaks in their chemical structures – and less data on their risks to the environment and human health.

4. Decision time

The industry’s leading carpet makers chose the substitutes.

Early PFAS chemicals had eight or more carbon atoms on their molecular chains. Chemists referred to them as “long chain” and “C8” compounds.

The new versions had six carbon atoms. These “short chain” products had soil- and water-busting traits but were supposed to be less toxic and break down more quickly.

The carpet mills kept running, and Shaw Industries continued to grow under Berkshire Hathaway’s umbrella. In the early and mid-2000s, Shaw moved aggressively into South Carolina. It bought Honeywell’s nylon plants in Clemson, Anderson — and the factory on the Lower Saluda River in Irmo. By 2005, Shaw Industries and Mohawk each had more than $5 billion in sales.

Then, in 2008, another crisis: A team led by University of Georgia researchers published a study about PFAS contamination on the Conasauga River. The Conasauga flows through Dalton into rivers that supply drinking water in Georgia and Alabama. Researchers found plenty of PFAS in the Conasauga. Some levels were among the highest ever recorded outside an industrial spill.

As the years passed, researchers found evidence that the short-chain replacements may also have similar environmental and health risks. Scientists began calling the short-chain replacements “regrettable substitutes.”

But it wasn’t until 2019 — nearly two decades after 3M’s announcement — that Shaw and Mohawk stopped using PFAS chemicals altogether, according to the companies. Soon, the industry’s PFAS legacy moved into another arena — the courts.

In 2024, Mohawk sued PFAS manufacturers, alleging they’d assured Mohawk “in no uncertain terms, that their products were safe.”

Mohawk declined an interview request for this story, referring to its lawsuit. But in a statement to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a Mohawk attorney reiterated that the company switched to products that “Mohawk was repeatedly assured were safer and more environmentally friendly than prior iterations,” and noted that “even to this day, no regulator has limited PFAS in industrial wastewater.”

In a statement, Shaw officials also said that its soil-blocking chemical suppliers consistently told them their products were safe. “Shaw acts in good faith to minimize the environmental impact of its manufacturing facilities,” its statement said.

While lawyers fought over who was responsible, the scope of the problem was undeniable: The invisible chemicals the carpet industry had used to make its products so popular also contributed to a massive public health and environmental crisis, especially in the Carolinas and Georgia.

In some parts of the country, such as Minnesota, Maine and New York, state officials took aggressive action to hold polluters to account.

But regulators in South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama mostly sat on their hands. In the absence of clear regulations, fed-up municipalities and citizens groups turned to the courts to recover costs of removing PFAS from their drinking water systems and waterways.

One of those lawsuits was in South Carolina and had begun with Bill Stangler’s canoe trip on the Lower Saluda, 280 miles from Dalton.

5. The South Carolina connection

Bill Stangler is 39 years old with a thin brown beard and a roguish look. When he was younger, he was a river guide on the Congaree when a big sewer spill made his fellow guides sick. That spill led to the formation of the Congaree Riverkeeperwatchdog group.

“Our agencies and local governments weren’t doing enough, and we needed a strong voice to stand up and protect the rivers,” Stangler recalled.

He eventually took over when the first riverkeeper left for a better paying teaching job. Soon after, Stangler discovered new sewer spills, including one that led to a multi-year lawsuit against a private sewer company. He’d seen firsthand how people and institutions do better when people are watching.

Stangler’s new focus on PFAS was a different kind of mystery. These forever chemicals didn’t have the stink of a sewer spill. No belly-up fish, no rainbow sheen of an oil release. They were invisible, which made them more difficult to identify and trace.

So that conference call in 2022 with the other riverkeepers had been a jolt — the one where he learned the Lower Saluda by the Shaw plant had some of the highest levels of a particular PFAS. Forever chemicals were a national problem and a local one.

Stangler dug into what the state of South Carolina had done to identify and solve the PFAS problem. He found a mixed bag.

In 2020, the state Department of Health and Environmental Control began testing public water systems for PFAS, then expanded testing to rivers and lakes and private wells. The agency focused on areas most likely to have PFAS contamination — from military bases and airports that used firefighting foam to waterbodies near fields that received sludge from sewer plants.

In 2023, DHEC revealed that virtually every water body they sampled had forever chemicals.

South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson then sued multiple PFAS manufacturers, citing the study and its conclusion that PFAS contamination in the Palmetto State was “ubiquitous.”

The scale of the problem was numbing. Researchers found PFAS in dolphins in Charleston Harbor and in hotspots near Sumter. The State newspaper revealed how PFAS-laden fertilizer sludge was spread on 80,000 acres of South Carolina farmland. These were forever chemicals and everywhere chemicals.

In Stangler’s mind, polluters had created the problem incrementally. Solutions likely would work the same way. He set out to find more evidence that the Shaw plant was a source of the PFAS readings in the cold, trout-filled water he’d spent years trying to protect.

Stangler studied permitting documents and satellite images. They showed how wastewater from Shaw’s plant went to sludge ponds and the Lower Saluda. He learned that in 2013, Shaw received a federal permit to release certain pollutants into the river, but not any PFAS chemicals. Stangler wondered: Did the company violate the Clean Water Act?

He needed more tests, ones more precise than those he collected in his first sampling round — a chemical match that might hold up in court.

He returned to the river in late 2023, paddling back to Shaw’s wastewater outfall. He took even greater precautions to avoid wearing PFAS-containing clothes, such as Gore-Tex raingear, or PFAS-containing sunscreen.

The results came back a few weeks later: The Lower Saluda by Shaw Industries contained at least 15 types of PFAS. Some were the “regrettable substitutes” that had replaced earlier PFAS variants.

Stangler called the Southern Environmental Law Center with the news. Together, they sued Shaw Industries in federal court, alleging the company had violated the federal Clean Water Act. The suit noted how West Columbia and Cayce drew its drinking water downstream.

“What it comes down to is this,” Stangler said of his thinking then, “does everyone have to play by the rules? Or do some folks get a free pass to shift the burden of their pollution to the rest of us?”

Now, Shaw Industries had another decision to make — fight the lawsuit or do something to clean up its mess.

6. Downstream

Kellie Ballew, Shaw’s vice president of environmental affairs, saw Stangler’s findings as another clue in a mystery the company’s engineers already were trying to solve. Ballew lived outside of Dalton in a mountain town with her wife, 50 chickens and 800,000 honeybees. An industrial engineer, Ballew had been with Shaw for more than 25 years. She’d played key parts in the company’s environmental sustainability efforts, including ones to manage PFAS chemicals. But on the surface, Stangler’s findings didn’t make sense.

Yes, Shaw’s plants in Dalton had used PFAS chemicals, mainly by applying them to carpet fibers near the end of the manufacturing process. But Shaw had stopped using PFAS chemicals in 2019, she said in a recent interview. And as far as she knew, the company’s plant in Irmo hadn’t used PFAS chemicals at all. (In a statement, the company said it didn’t use PFAS-based soil resistant materials in any of its South Carolina plants.) Where were they coming from?

She and her colleagues had been analyzing water flowing into Dalton’s mills and the mills’ wastewater. Their tests in some cases showed higher levels of PFAS in wastewater than the intake water, she said. This meant that somewhere in those plants, forever chemicals were still being released. This was so even though the company had stopped using PFAS, she said. Now, they saw a similar pattern in Irmo.

They looked at oils and liquids at their plants, including Irmo’s, along with materials from their suppliers. Nothing.

“You’d send it to the lab and you’d get back a whole bunch of non-detects,” she said.

Then a scientist on her team realized they weren’t testing the substances in real-life factory scenarios, with chemistry-altering heat and pH changes that typically happen in industrial facilities. Shaw engineers invented new tests, and there they were: PFAS chemicals in heat transfer fluids, in reactions to make nylon — PFAS chemicals in more than 60 materials the company used in all of their plants, including Irmo.

“I remember I was driving home from work, and my colleague that works on this with me called me,” Ballew said, “and he teared up because we had that moment of all this frustration culminating with this amazing discovery, and that if we can simulate it in the lab, we can see it and do something about it.”

Stangler’s findings came during this detective work, Ballew said. Instead of fighting Stangler and the Southern Environmental Law Center in court, Shaw officials proposed a solution: They would install a granular activated carbon system in Irmo at a cost to Shaw of more than $500,000.

The filtration technology was a cousin to what you might find in a Brita water filter, but on an industrial scale. If the system worked, it could remove PFAS that otherwise would drain into the Lower Saluda. Stangler and the attorneys withdrew their lawsuit as Shaw’s engineers ran tests.

The filters have a varied track record. The city of Gadsden, Ala., sits downstream from Dalton’s carpet companies. It installed a carbon system to lower PFAS levels to what the EPA deemed safe. But it didn’t do the job, and the city is switching to a more expensive reverse osmosis technology.

The Irmo project has a different goal, Ballew said. The company isn’t trying to get to zero PFAS. Instead, Shaw wants to reduce PFAS levels in wastewater to the same levels it sees in water piped to the plant. In other words, she said, “We’re just trying to not add to those background levels.”

So far, the technology seems to be working, she said. In the meantime, Shaw applied for a patent for its PFAS testing process. In some cases, Shaw’s suppliers didn’t know their materials had forever chemicals, she said. Now, those companies might be able to reduce PFAS in their products — for Shaw and others.

“It’s really a cathartic moment where you see a path to a solution, a path to helping our company, and a discovery we could share with the world,” Ballew said.

***

Last fall, Stangler was back on the Lower Saluda on a warm afternoon. About three years had passed since Stangler’s sampling trip opened a door to the PFAS mystery in his watershed. The air was still. Leaves fell gently into the cinnamon-colored current; their tips were curled so they looked like tiny orange sailboats. They bobbed as Stangler guided his jetboat toward the place where Shaw’s wastewater met the river.

Stopping for a moment, he began talking about how not every environmental fight has to end up in court, how what happened behind the screen of trees could be a model for the rest of the state and beyond.

He said that South Carolina regulators could require other industrial PFAS users to install filtering systems. The state didn’t need any new regulations to make progress on PFAS, he said. Federal clean water laws already are powerful levers. “They could do it today.” All it would take, he said, is the guts to tell polluters that they need to stop polluting the state with PFAS and shifting those costs to the public.

It’s unclear whether Departmental of Environmental Services, the successor to DHEC, has the stomach for that. Top officials with DES declined interview requests from The Post and Courier about how the state could be more aggressive in enforcing existing pollution laws.

The agency instead sent a statement that pointed toward the lack of enforceable federal standards.

“Until PFAS are regulated by all relevant agencies,” the statement said, “these contaminants will continue to be prevalent in our environment and people will continue to ingest or otherwise be exposed to them on a routine basis.”

In the meantime, Stangler and the lawyers at the Southern Environmental Law Center are waiting for Shaw’s final filter results, though they know waiting carries risks, too.

They know that 97 percent of Americans have PFAS in their blood, and how by one estimate upwards of 172 million people across the United States have PFAS in their drinking water.

And they know that PFAS helped create better products, but that its dark side shouldn’t be ignored — that if polluters aren’t held to account, the leaves will continue to fall, the cold river will flow, but the chemicals will remain forever.

Glenn Smith and Marilyn W. Thompson of The Post and Courier contributed to this report.

This story is part of an investigative collaboration with AL.com, The Associated Press, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and The Post and Courier that includes the upcoming FRONTLINE documentary Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy. It is supported through AP’s Local Investigative Reporting Program and FRONTLINE’s Local Journalism Initiative, which is funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Watch the documentary Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy at pbs.org/frontline and in the PBS App starting Feb. 3, 2026, at 7 p.m. EST or on PBS stations (check local listings) and on FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel at 10 p.m. EST. It will also be available on the PBS Documentaries Prime Video Channel.

Watch the full documentary

Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy

How did PFAS chemicals once used in popular stain-resistant carpets end up in the water and environment in parts of Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina?

Keep Our Journalism Strong. Donate Today.

Your support makes it possible for FRONTLINE to produce bold investigative documentaries on the issues that matter most. Donate today to help sustain this work through the months and years ahead.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.