How Rarely Seen Archival Footage Brought a Civil-Rights-Era Story to Life

February 15, 2022

Share

In the summer of 1965, filmmakers Ed Pincus and David Neuman traveled to Natchez, Mississippi, to make a documentary about the civil rights movement’s impact on a community.

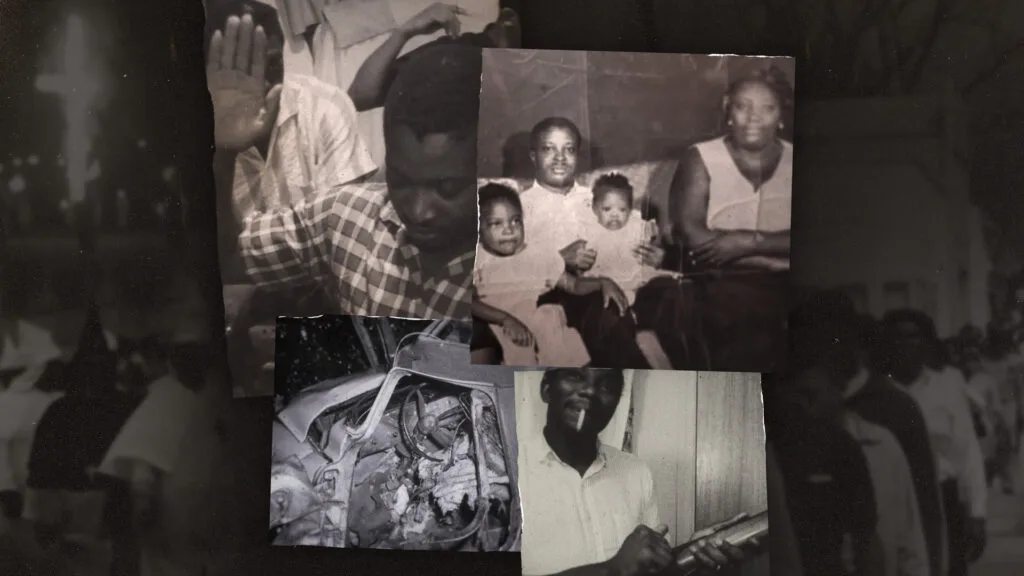

While they were filming that August, a car bomb targeting Natchez NAACP president George Metcalfe left him critically injured and outraged the city’s Black community. Metcalfe survived, but the incident would reshape the documentary Pincus and Neuman went on to produce: Black Natchez.

Nearly 60 years later, the footage the filmmakers captured that summer, as well as when they returned in 1967, would become a cornerstone for a different documentary about another Natchez family’s search for justice.

Premiering this month, American Reckoning, produced and directed by Brad Lichtenstein and Yoruba Richen for FRONTLINE and Retro Report, examines another targeted bombing two years later in the same community: the killing of Wharlest Jackson Sr., treasurer of the local branch of the NAACP. The documentary draws heavily on archival material, including rarely before seen footage shot by Pincus and Neuman decades earlier, and also explores an ongoing federal effort to investigate civil-rights-era cold cases.

“Filmmaking is a visual medium,” Lichtenstein said. “You’ve got to have footage if you’re going to tell the story.”

FRONTLINE talked to Lichtenstein and Richen, experts in African American history and film studies, and Pincus’ widow about Black Natchez and additional footage shot by Pincus and Neuman.

Finding the Footage

The hour-long documentary Black Natchez premiered in 1967 on National Educational Television (NET), the predecessor to the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). In cinéma vérité style, the filmmakers documented the Black community’s response to the 1965 bombing of Metcalfe’s car and the civil rights organizing that followed.

With intimate access, Pincus and Neuman filmed inside barber shops and church meetings, capturing the debates that took place as Black residents discussed how to get the city’s leadership to respond to demands submitted after Metcalfe’s bombing. And they captured the tension between the NAACP, led by Mississippi field director Charles Evers, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, as well as between Black residents of different economic classes.

Pincus and Neuman filmed more than what made it into their documentary, both on their original trip to Natchez and when they returned after Wharlest Jackson Sr.’s killing. Outtakes include the NAACP-led boycott of local white-owned businesses and behind-the-scenes organizing by the Deacons for Defense and Justice, a group of armed Black residents who sought to protect the community from acts of violence.

Although Lichtenstein and Richen said Pincus and Neuman’s archive of footage had a significant influence on their work, their documentary started elsewhere — with the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis.

Lichtenstein, who had known Lewis for a long time, had talked to the civil rights icon about making a film on forgiveness — an idea born out of an incident in which a man who had beaten up Lewis and other civil rights workers in the 1960s later asked Lewis for forgiveness.

In discussing the idea with Lewis, Lichtenstein said they came “to the conclusion that a film about forgiveness leaves out a big part of the story, which is the terror and the accountability.”

That’s when Lichtenstein began to learn more about a federal effort championed by Lewis: the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act. The 2008 law was designed to re-examine civil-rights-era cold cases. “Every single one of these lives deserves some kind of public memorial,” Lichtenstein said.

Explore: The “Un(re)solved” Interactive

While researching the names of victims on the Till Act list, he came across the 1967 killing of Wharlest Jackson Sr. and discovered Black Natchez, which was released that same year. “I was struck by what an immersive kind of film it is,” Lichtenstein said.

In 2016, Lichtenstein asked Richen to partner with him in making American Reckoning. Richen recalled that when, on Lichtenstein’s recommendation, she first watched Black Natchez and the additional footage, she was struck by its distinctiveness. “It was just this incredible document of the terrorism that was going on in the town and the Black resistance to it,” she said.

The two began working on a short film with Retro Report, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on adding historical context to current events. Soon the collaboration expanded to FRONTLINE. Richen said everyone was excited about the opportunity to draw on the archival footage. “We were all, I think, on the same page of, [the more] we can tell this story of this man, this family, this murder, this terrorism, as much through the archive as possible, the better.”

The team was especially enthusiastic about including some of Pincus and Neuman’s footage that had never been shown publicly. “We’re trying to say that our history is important to scrutinize and investigate, as much as our present,” said Raney Aronson-Rath, FRONTLINE’s executive producer who, along with filmmaker Dawn Porter, served as executive producer on American Reckoning. “And you don’t understand the present without understanding what actually happened in this trauma that has now gone on now, for generations upon generations. It’s important for us to report on, investigate and show to the world.”

Lichtenstein had connected with the Amistad Research Center, an independent archive and library housed on the campus of Tulane University in New Orleans, and met Brenda Flora, Amistad’s curator of moving images and recorded sound.

She told Lichtenstein that Pincus, who passed away in 2013, had donated Black Natchez and dozens more hours of footage to Amistad in 2002 for long-term preservation. For years, most of the footage was only viewable in-person, with the assistance of an archivist. With the support of the Council on Library and Information Resources, Amistad digitized 85 hours of original material, including outtakes from Black Natchez, a short 1970 documentary called Panola, and additional footage Pincus and Neuman shot in 1967 for a follow-up documentary that was never finished. Lichtenstein and Richen estimated they used around four minutes of Black Natchez in American Reckoning, with the balance of footage shot by Pincus and Neuman coming from Amistad’s archives.

When Lichtenstein first approached Amistad, the documentary and related footage had not yet been digitized, but Flora said his interest in the material helped the center acquire funding. “He was really instrumental,” she said. “We kind of supported each other to get our projects completed.” The entire collection is now available to view online.

Documenting a Civil Rights Moment

Black Natchez was the first full-length documentary from Pincus and Neuman, both young Harvard University graduates living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ed Pincus’ widow, Jane Kates Pincus, told FRONTLINE: “Ed asked David [Neuman] if he’d like to go down South and make a film. Neither of them had ever done anything like that before.”

Pincus operated the camera, while Neuman captured sound. They hadn’t set out to make a film about a bombing and the community’s response. Jane Kates Pincus said their plan was to cover “freedom schools” — launched as part of the 1964 Freedom Summer, with the goal of providing educational opportunities for Black children at a time when much in the South remained racially segregated.

“We wanted to find a quiet town where civil rights activity was just beginning, in such a way that we could sort of see what impact the civil rights movement would make on a community …,” Pincus said in a 1967 interview with WGBH. At the time, the Ku Klux Klan was active and violent in Natchez, with both the United Klans of America and White Knights of the KKK operating in Mississippi.

Listen: The “Un(re)solved” Podcast

The tactics civil rights activists employed in Natchez starting in 1965 were “very important, particularly for the state of Mississippi,” according to Akinyele Umoja, a professor of African American studies at Georgia State University and the author of We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance and the Mississippi Freedom Movement, who appears in American Reckoning.

“You see debates in the Black community about what strategies should be used,” he said, referring to scenes where residents discussed picketing, marching and taking up arms for protection. Those conversations were important not just to Natchez, he said, but to “Mississippi, which is a key Southern state — in terms of, particularly, the numbers of Black people, and the level of violence, and the level of segregation.”

The Natchez boycott of white-owned businesses was one of the first to combine economic pressure with armed protection and enforcement, according to Umoja. Other towns in Mississippi replicated that model, he said, using local resources to bring about change on a local level.

According to Umoja, six white businesses closed within weeks of the Natchez boycott. Once residents reached an agreement with city leadership, 23 white-owned businesses agreed to hire Black employees, the city hired six Black police officers, and several public institutions were desegregated.

Umoja, who came across Black Natchez in his own research, said he was “shocked” when he saw Pincus and Neuman were allowed to film a swearing-in ceremony for a Black armed self-defense group. “I think that’s a rare moment for them to be able to capture that,” he said. “It shows they had built up a certain level of trust, to even have access to people on that level.”

Umoja said it was common for civil-rights-era documentaries to capture meetings, demonstrations and speeches, but much less common for filmmakers to be invited to record a community’s internal debates. Remarking on the access Pincus and Neuman — two white Natchez outsiders — were able to obtain, Umoja asked, “How could they be in that type of intimate space, where debates were going on and people were really telling how they feel about other people in the room, in the Black community?”

In his 1967 interview with WGBH, Pincus said he and Neuman lived within the Black community while filming, “in great part, trying to become members of that community, in such a way that we could film freely and have access to people without great difficulty.” Jane Kates Pincus said the filmmakers remained in places long enough that they became “invisible.”

Black Natchez “records a particular moment in time, in a place, by two people who were not of that place, who managed to make such a — I think of it as both active and filled with drama and events, and yet a very pure film,” she said. “It just makes me very grateful that their work, which was unusual and inspiring, is being recognized.”

Documentaries Across Decades

When Black Natchez aired on NET in 1967, the NAACP’s executive director at the time, Roy Wilkins, took exception. He wrote to the president of an NET-affiliated station in New York, saying the documentary depicted the NAACP in a way that was “grossly unfair” and “bordering on the libelous.” (Wilkins took issue in part with narration by James Jackson, who, as a founding Deacon, helped protect local NAACP leaders and the Black community. In NET’s broadcast of Black Natchez, James Jackson complained about the pace of change: “We almost just about right where we started.”)

NET’s then vice president, Edwin Bayley, apologized to Wilkins but stood by the filmmakers, saying Black Natchez did “present a true picture of the Natchez experience as seen through local eyes.” Although Wilkins called the filmmakers’ effort “commendable,” he insisted the NAACP was shown as “willing to accept anything and even nothing offered by the white city officials.”

Allison Perlman, an associate professor of history and film and media studies at the University of California, Irvine, shared the above exchange from the Papers of the NAACP archive. She said NET’s documentaries of the 1960s differed from what was seen on TV elsewhere. While commercial networks spotlighted nonviolent civil rights efforts, she said, NET didn’t shy away from showing armed resistance or Black radicalism, not as “something for audiences to be afraid of, but something to understand and contend with.” According to Perlman, NET often prioritized “Black voices and Black perspectives,” compared to some other broadcast programming that used a “voice of white authority.”

In his 1967 interview with WGBH, Pincus defended Black Natchez, saying he and Neuman spent a year editing the film and had many discussions about how to present events and perspectives. “I think that, ultimately, the criterion that we used most for deciding what was to be in the film was what was most honest, what was most typical of the community,” he said.

The American Reckoning film team said Pincus and Neuman’s material — both Black Natchez and the additional footage — ended up being “central” (Lichtenstein) and “foundational” (Richen) to their own documentary, providing a valuable historical record of the civil rights movement in Natchez.

But when Richen first watched it, she said she wondered, “If Black people had made this film, what would it have looked like? How would it have been different, if it would have been different? We weren’t given access, obviously, at that time to tell our own stories.”

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.