Facing Eviction

July 26, 2022

54m

Families struggle to keep their homes during the pandemic, despite a federal ban on evictions

Facing Eviction

July 26, 2022

54m

Share

Why have some American families struggled to keep their homes during the COVID pandemic, despite a federal ban on evictions? With Retro Report, the documentary Facing Eviction offers an intimate look at the United States’ affordable housing crisis through the eyes of tenants, landlords, judges and law enforcement.

Produced by

Transcript

Credits

Journalistic Standards

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

‘Wherever I Am Is Her Home’: A Mother and Her Young Daughter Navigate Eviction

How Moratoriums & Rental Assistance Impacted Evictions in the U.S. During COVID-19

Poverty, Politics and Profit

Related Stories

Watch 2022’s 10 Most-Streamed New FRONTLINE Documentaries

How Moratoriums & Rental Assistance Impacted Evictions in the U.S. During COVID-19

‘Wherever I Am Is Her Home’: A Mother and Her Young Daughter Navigate Eviction

What Happened to Poverty in America in 2021

Burden of Richmond Evictions Weighs Heaviest in Black Neighborhoods

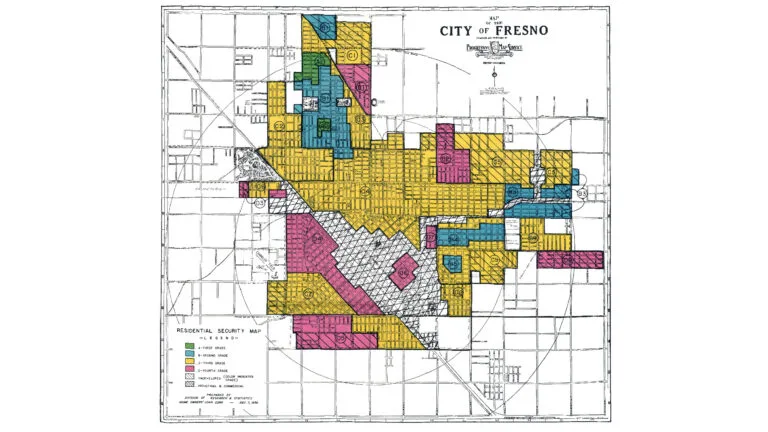

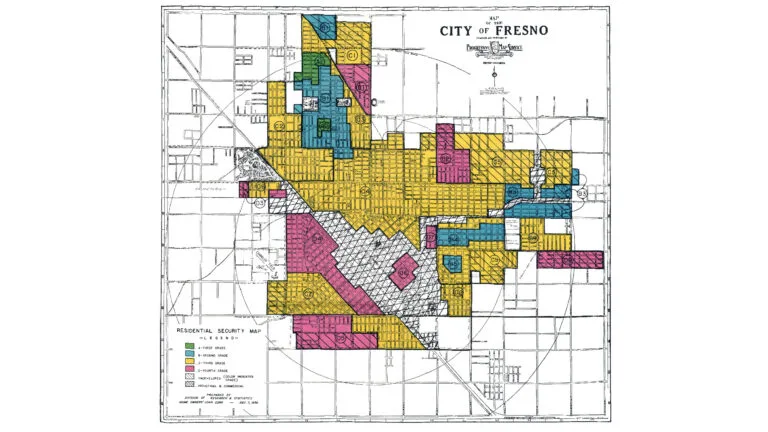

How Decades of Housing Discrimination Hurts Fresno in the Pandemic

New York Tenants Are Organizing Against Evictions, as They Did in the Great Depression

Tenants Facing Eviction Over Covid-19 Look to a 1970s Solution

5 Years Later, A Look Back at How the COVID-19 Pandemic Disrupted the World

Poverty, Politics and Profit

Evictions and the Pandemic

The Housing Fix

Related Stories

Watch 2022’s 10 Most-Streamed New FRONTLINE Documentaries

How Moratoriums & Rental Assistance Impacted Evictions in the U.S. During COVID-19

‘Wherever I Am Is Her Home’: A Mother and Her Young Daughter Navigate Eviction

What Happened to Poverty in America in 2021

Burden of Richmond Evictions Weighs Heaviest in Black Neighborhoods

How Decades of Housing Discrimination Hurts Fresno in the Pandemic

New York Tenants Are Organizing Against Evictions, as They Did in the Great Depression

Tenants Facing Eviction Over Covid-19 Look to a 1970s Solution

5 Years Later, A Look Back at How the COVID-19 Pandemic Disrupted the World

Poverty, Politics and Profit

Evictions and the Pandemic

The Housing Fix

Texas

April 2021

ALEXYS HATCHER, Arlington tenant:

Yesterday I came home with a 24-hour notice to vacate on my door. I have a 5-year-old, so just trying to understand how this is going to affect her, knowing the pandemic has already affected her a lot. So it’s just been hard.

It takes more than 24 hours to plan out your life. You begin to think about what’s most important to you, things that you can pack quickly and keep with you just in case you’re not with your things for an extended amount of time. Right now, our things are going to go to a storage.

FEMALE VOICE:

And where are you sleeping tonight?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

I haven’t figured that out.

NARRATOR:

The coronavirus pandemic put tens of millions of Americans at risk of being evicted. To protect them, the federal government ordered billions in rent relief and a temporary ban on evictions, first through the CARES Act, later through a moratorium issued by the CDC.

JUDY WOODRUFF, PBS NewsHour:

In an unprecedented move, the Trump administration announced a temporary national moratorium on evictions for tens of millions of renters who’ve lost work.

NARRATOR:

Over the course of a year, we went to states across the country to see how the protections were being carried out—

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

Time is running out to keep families from being kicked out of their homes.

NARRATOR:

—and how the effectiveness depended almost entirely on how local officials were enforcing it.

GAYLE KING, CBS Mornings:

And some states have put a short-term hold on all evictions, but protections are hodgepodge.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

There’s a patchwork of eviction policies that vary by state.

NARRATOR:

Tenants scrambled to understand what their rights were—like Alexys Hatcher in Texas, a state that already had limited protections for tenants.

MARK MELTON, Dallas Eviction Advocacy Center:

When the pandemic really started hitting strong in the United States and we started to see business closures and eviction moratoriums, I just started posting explainers on social media, just to help people understand exactly what was out there and how it would apply to them. Those posts started to be shared quite a lot. And so before I knew it, I was getting phone calls and emails and Facebook messages and tweets and everything else from people all over the county asking for advice on their particular situations.

NARRATOR:

Mark Melton, Hatcher’s attorney, created a network of lawyers to help people at risk of losing their homes.

MARK MELTON’S PARTNER:

This landlord is trying to evict her by email. That’s cute.

MARK MELTON:

By email, huh?

MARK MELTON’S PARTNER:

Yep.

MARK MELTON:

The government interventions that we’ve had to date have been helpful, certainly. But the problem with this protection is it’s not very effective because it doesn’t apply automatically. It only applies if those tenants know about the law well enough to sign an official declaration that they have to give to their landlord and the court for it to apply.

Hello, is this Jane? What’s going on? I saw your message today at 1 o’clock.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

Well, yes, I’m still behind on my rent, but the thing is, is my auntie was talking about some type of paper that don’t show us the late fees or something.

MARK MELTON:

Well, the late fees are still chargeable, but what city do you live in?

These are not deadbeats. These are people that had jobs, that felt secure, and then all of a sudden the business that they work for is closing or they’re furloughing people. It was taking months to get unemployment insurance to go through because there was such an over-log of applicants that the state just couldn’t process them quickly enough. And so people were really in a bad situation where they had no real options.

They can’t force you to leave your home until a court orders them to, or orders you to leave.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

Yes, I know, I know.

NARRATOR:

In February 2021, a federal judge in Texas cast doubt on the validity of the CDC moratorium, saying it had overstepped its authority.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

The CDC’s moratorium on evictions is unconstitutional. The judge ruled that while individual states have the power to put such restrictions in place, the federal government does not.

NARRATOR:

And then, separately, the Texas Supreme Court began allowing evictions to move forward, which left many people like Alexys Hatcher in a precarious situation. She became one of the first in the state to be evicted. She had been a manager of a shoe store, which closed during the pandemic. She lost her income and fell behind on her rent.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

Court documents for her eviction case show Hatcher filed the necessary CDC declaration, saying she faced homelessness. Still, this week a judge allowed for the eviction to move forward.

MARK MELTON:

Effectively, what happened with Alexys was the CDC moratorium was still there. It didn’t go away. But Texas courts decided that the CDC order no longer applied in Texas, as crazy as that is. They started allowing landlords to evict people at will.

EMILY BENFER, Eviction Lab:

In Texas you have one of the first states to challenge the CDC moratorium, and successfully so.

NARRATOR:

Throughout the pandemic, Emily Benfer was tracking how states were handling evictions.

EMILY BENFER:

Much of a tenant’s experience during the pandemic was completely dependent upon the ZIP code that they lived in. Whether or not you stayed in that home depended almost entirely upon whether or not your landlord was going to comply with the CDC moratorium—or a local moratorium, for that matter— what sheriff showed up at your door and what judge you appeared before.

NARRATOR:

There were some judges in Texas still willing to consider the CDC moratorium.

MALE COURT BAILIFF:

The county of Dallas, the state of Texas, the Honorable Judge Katina Whitfield presiding, is now in session.

JUDGE KATINA WHITFIELD, Dallas County Justice of the Peace:

Good morning, everybody. Let’s get started here.

Sir, can you hear me?

MALE VOICE [on video call]:

Yes, ma’am.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Oh, OK, great.

In Texas, a federal court judge did state that the CDC moratorium is not constitutional. I have mixed feelings about it because we had the tenants that we know were affected.

I see that there is going to be a lot of emotional cases that will be before me.

I have to visit the moral obligation a lot more because the legal obligation is in black and white. It does not take into account the gray areas, and that’s the reason why I listen to both sides, because once you do that, that gray area is going to be exposed.

Susanna, is the $2,219 the current amount owed?

FEMALE VOICE:

$1,921.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Have you tried to—OK, first, I don’t—you don’t have to go into your particular circumstances of what caused you to fall behind, but if you would like to explain what happened, you can do that.

MALE VOICE [on video call]:

Well, what happened was I was dealing with the COVID, then I got laid off about two, three weeks. And then once I come back to work, it was just like part-time gigs. And then I ended up losing my job.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

A lot of the people who were truly affected by COVID, they’re no better now than they were a year ago. We’re talking about them losing their homes, or their kids will have to be withdrawn from school, whatever. The stakes are high. So if we have that type of situation, number one, y’all need to understand it. Put yourself in their shoes.

NARRATOR:

Texas had started a new program that ordered judges to encourage landlords and tenants to work together to avoid evictions. Judge Whitfield spent time explaining to tenants that there were still protections available to them.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Right now, you’re not considered a covered person because you haven’t filled that declaration out and submitted it to your landlord. By what you testified to, it sounds like this would apply to you, but you would need to read each and every bullet point very carefully and sign it, because you have to qualify under each one of these, OK? You would sign it, you would submit a copy to your landlord and a copy to the court. As of today, you’re not a covered person, OK? So I would have to grant them judgment, but that doesn’t mean that it’s too late to fill this out. We’re also going to email you guys a list of resources. We have a packet of financial resources.

OK, judgment in favor of the plaintiff for thirty-three oh eight nineteen. Possession and court costs. Best of luck to you. Go down there, make the arrangements, pay off what you can and try to settle it, OK?

FEMALE VOICE [on video call]:

Yes, ma’am.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

All right. Thank you guys so much. You have a wonderful day.

FEMALE VOICE [on video call]:

You, too.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Thanks.

FEMALE VOICE [on video call]:

Good afternoon.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Same to you.

NARRATOR:

In making her decisions, Judge Whitfield said she also had to balance the financial concerns of small landlords, who were often more vulnerable than corporate property owners.

KATINA WHITFIELD:

Since COVID, the mom and pop—you know, this is not a business. I have one home that I’m renting out. I still have a mortgage, HOA fees, insurance and those type of things. I always stress the financial assistance and I remind the tenant that this person is still paying those things. You have to remember that just because it’s hard on you, remember that it’s just as hard on them.

NARRATOR:

Landlord Sandra Stanley quickly began feeling the impact of the pandemic.

SANDRA STANLEY, Dallas-Fort Worth landlord:

Hi, George. I’m here, I’m just checking on you to see if you need anything. How’s it going?

MALE TENANT:

How are you?

SANDRA STANLEY:

I’m good.

NARRATOR:

She and her family own eight rental properties around the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

SANDRA STANLEY:

Thank you for the partial payments, and just continue to communicate and talk to me.

Local landlords have up-close-and-personal relationships with their tenants. We know our tenants. We know their children. We know what’s going on with them, their situations. Over the course of the pandemic when I had to work with people with their rent, we did OK paying our mortgage that we had on it, but we did have struggle with paying our taxes.

Hey, Steve, this is Sandra.

MALE VOICE [on phone]:

Hey, Sandra, how are you?

SANDRA STANLEY:

I was wondering, did you get to find a solution to that AC problem at all?

We have to take care of the properties regardless of if we get paid or not. We had A/C repairs, we had a plumbing problem. All that money has to come out of my pocket, so I went into my retirement and got the money to pay the taxes. And my brother, he had a savings, he had to go in his savings.

In my lifetime of being a landlord, I’ve had to do at least three evictions, probably over 30 years. We really tried to work with people and charge low rent so they can pay their rent. I’d rather have somebody pay their rent than have eviction. I hate doing evictions.

NARRATOR:

Throughout the pandemic, the people on the front lines of carrying out evictions in Texas were deputies from the local constable offices.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

My name is Jacqueline Lundy. I work for the Dallas County Constable’s Office, Precinct 5.

I’m gonna put in my first address.

When I’m driving out to the location, I kind of try to run some scenarios in my head: OK, if they’re not at home, fine. But if they are at home, what is my next step? What am I going to do? How am I going to approach it? You don’t know what state of mind they’re in. We’re in a pandemic. People have lost their jobs, whatever home life that they have going on. Their emotions could be high.

Sometimes it’s—you kind of are sensitive to the situation. You just kind of have to compartmentalize the sad part of it. It is sad. For me, I would prefer if they were not home, but it’s a roll of the dice when they are at home. And if they are at home, it tugs at you if there’s kids involved, because it’s not their fault that they’re being displaced. But for the most part, it’s about safety. You don’t know who’s behind that closed door, so it’s an unknown, and an unknown is going to be a threat.

NARRATOR:

Deputy Lundy was on her way to evict a man who had been illegally occupying a vacant house for months.

Body camera footage

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Just open the door.

MALE CONSTABLE 1:

We need to speak with you out here.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Open the door, we’re going in.

MALE CONSTABLE 1:

Oh, he has it locked. He locked the door.

MALE CONSTABLE 2:

Listen, we don’t have time for all this. I got a court order.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Hey, hey!

MALE OCCUPANT:

That doesn’t have my name on it. [inaudible] paying attention.

MALE CONSTABLE 2:

You need to open the door.

MALE OCCUPANT:

He did not give me a read to writ. I have never met that man before in my life.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Get something to open the door.

MALE CONSTABLE 2:

Let’s discuss this outside. We need to get you out of the house.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Yeah, something to pull the door.

MALE CONSTABLE 2:

Come on.

MALE OCCUPANT:

What do you have a gun out for? I don’t have a weapon on me.

MALE CONSTABLE 2:

Because don’t know what you got inside the house.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Open the door.

MALE CONSTABLE 1:

Open the door.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Open it, open it. Get in there, get in there.

MALE OCCUPANT:

I ain’t worried about no five-oh. I’m packing my s—. You come in and help me. I’m packing my stuff.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

You need to step out.

MALE OCCUPANT:

I’m getting all my belongings.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

You need to step out!

MALE OCCUPANT:

I can’t get my clothes?

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Uh-uh. Step out. Let’s go. Step out.

MALE OCCUPANT:

Man, don’t touch me, man.

MALE CONSTABLE 3:

Taking everything out of the house! We’ll take everything out of the house. Saque todo de la casa.

JACQUELINE LUNDY:

Put everything over here in the front yard. All the furniture.

Alexys Hatcher’s grandmother’s house

ALEXYS HATCHER’S GRANDMOTHER:

Did you—you got to say grace? OK, say grace.

EMILY BENFER:

The greatest indicators of eviction are being Black, being a woman or having children. We know that Black people are two times as likely to be evicted as their white counterparts after controlling for education and other factors. We know that the single greatest predictor of an eviction is the presence of a child.

NARRATOR:

The day she was evicted, Alexys Hatcher and her daughter spent the night at her grandmother’s house. But she was worried about COVID and continued looking for somewhere else to stay.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Are you on the southern side of Arlington or on the northern side?

ALEXYS HATCHER’S GRANDMOTHER:

Southern.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

OK.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR [on phone]:

Good afternoon. How could I help you?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi. I was wondering if you guys have anything available for maybe a week.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR [on phone]:

For a week starting today?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Possibly, yes.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR [on phone]:

So if you come in tomorrow, I’ve got a king room available at $99 per night.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

OK.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR [on phone]:

That’s a week’s stay, Saturday through the following Saturday.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Saturday to Saturday?

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR [on phone]:

Yes, ma’am.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

They’re so expensive. [Laughs] God.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 2 [on phone]:

Good afternoon. Can I help you?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi. I just have a couple of questions. First, I was wondering if you guys have anything that’s available for maybe a week?

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 2 [on phone]:

No, we don’t have anything. We probably wouldn’t be able to get you till Sunday or Monday.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 3 [on phone]:

Yes, ma’am. How can I help you?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi. So we were talking about the one-week room. I couldn’t remember if you said it would be available today or tomorrow.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 3 [on phone]:

Hold on, I’ll check.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Just one adult and one child.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 3 [on phone]:

One adult and one kid. OK, I got you booked. I’ll see you tomorrow.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

OK, thank you so much.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 3 [on phone]:

This is $375, OK?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Yes, ma’am. Thank you.

FEMALE HOTEL OPERATOR 3 [on phone]:

I’ll see you, bye-bye. You’re welcome.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Bye-bye. [Sighs] I know! We got that done, right?

ALIYAH HATCHER, Alexys’ daughter:

Yay!

ALEXYS HATCHER:

I’m glad that I have the daughter that I have, because not all kids are so understanding and accepting. She feels my energies. She knew something wasn’t right. She was expecting something was going to happen, but one thing she knows is Mommy’s always there. Mommy’s still here, so it must be OK. Even though she knows her stuff is not at home. Even though she knows we’re not going back there, she doesn’t know we don’t have a home, because to her—I’m sorry. [Cries] But to her, wherever I am is her home.

New Jersey

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

More than 15,000 eviction notices have been sent out to New Jersey residents during the pandemic even though New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy issued an eviction moratorium preventing people from being locked out.

NARRATOR:

Even in states with strong tenant protections during the pandemic, people were facing eviction. In New Jersey, in addition to the CDC moratorium, they passed their own ban on evictions for failing to pay rent. But that didn’t cover everyone.

JUNE ROBINSON, Newark tenant:

I used to work at HelloFresh, but I stopped working there because someone on my line had corona. Now I’m a temp, so—and a floater. I was only back a month and a half and I found out the landlord said I was a squatter. I mean, now I just sit and worry for the simple fact I got an 11-year-old daughter.

NARRATOR:

In December 2020, June Robinson’s landlord went to court claiming that she wasn’t a legal tenant because her name wasn’t on the lease and he hadn’t received rent since before the pandemic—even though she said she’d paid until recently.

NICHOLAS BITTNER, June Robinson’s attorney:

Ms. Robinson explained that she’s behind on rent right now, like a lot of tenants are in New Jersey.

The New Jersey governor and the Supreme Court essentially said that eviction cases couldn’t go forward. But the landlord filed this ejectment action, which were still allowed to be filed, claiming that June was not a tenant here. You’re essentially filing a lawsuit against someone saying they’re a squatter. We’ve seen it happen a few times over the course of the pandemic where a landlord says, “I can’t file for eviction, so can we get them out with an ejectment?” It’s possible that this is an attempt to just get around the protections.

JUNE ROBINSON:

I spend the majority of my time now sitting outside in my car, trying to figure it out. Is this how I’m going to be living, in my car? [Cries]

NARRATOR:

Before she found an attorney, Robinson had an online court hearing.

JUNE ROBINSON:

See if that Zoom thing got downloaded.

Yes, good morning. I’m supposed to have had a Zoom court date today, and I don’t have a link or anything on my phone. I never got—someone called me like the fifth, I think, the fourth or the fifth, and said I would be getting an email so I can do the Zoom video or something. And I never got an email. That’s all that was told to me.

While you’re here on the phone, let me—I’m going to go—no, I’m on the—OK, say, Joanne? That’s it? Could you tell me how to go about setting it up, please? Oh, don’t click on it now? OK. Oh, you are such—thank you so, so much. Because I didn’t know what to do.

I have a banging headache. Like, my head is hurting really bad.

FEMALE FRIEND:

Mmm-hmm. From being overstressed.

NARRATOR:

On the day of her hearing, she was running an errand at a grocery store and was in her car when the proceedings began.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

Ms. Robinson, are you here?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Yes.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

So maybe you could, it would not be inappropriate for you to remove your mask? So we could hear you better?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Oh. Oh, maybe. OK.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

OK, that’s much better. Before we go any further, please raise your right hand. Do you swear or affirm the testimony you are about to give, as well as the testimony you’ve previously given, will be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Yes.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

OK, thank you. Now, on Jan. 6, I heard testimony and reviewed the documents. And I concluded that whoever was residing at Unit 2 was not there with the permission of the property owner, and that anyone who was in that unit needed to vacate the premises immediately. So explain to me now what it is that you’re asking.

JUNE ROBINSON:

How am I squatting when the apartment was rented to me since July 2019?

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

Have you been paying anybody any rent?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Yes, I have. And like I said, yeah, I didn’t—I was back a month and a half. And that’s because I was out of work, but I started getting unemployment. And I told them that I would take and, you know, catch up on my rent.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

Is your name on the lease?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Yes. Yes, it is. Yes, it is, Your Honor. Yes.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

Well, let’s see it.

JUNE ROBINSON:

I’m in the car. I went to the store, Your Honor, to get something to eat. I didn’t know that—I didn’t bring no lease right here in the car with me.

LANDLORD’S ATTORNEY [on video call]:

My client, who is the lawful and legal owner of this apartment complex, Your Honor. And now we’re in a position where this person is purported to be a lease—a lessee of this residential apartment building yet has never prepared or shown a lease agreement, has never presented that to a court.

MALE JUDGE [on video call]:

I’m still trying to understand what is different than what occurred when I had a hearing in early January. Nothing has been presented to me today either verbally or in the documents provided to the court to enable me to vacate the prior order of ejectment. So good luck and stay safe.

LANDLORD’S ATTORNEY [on video call]:

Thanks, Your Honor.

JUNE ROBINSON:

I’m not understanding nothing he said. Like, so what he just said—this is just over? My thing is just over? Like—hello?

Three weeks later

JUNE ROBINSON:

Who is it?

DETECTIVE TOONE:

How are you doing, ma’am? You’re aware of what’s going on today, right?

JUNE ROBINSON:

No.

DETECTIVE TOONE:

Your brother hasn’t been talking to you?

JUNE ROBINSON:

No.

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

We came by multiple times. I’ve talked to you personally multiple times.

JUNE ROBINSON:

I don’t know why they keep—why he keeps sending y’all out here. This is a tenant-landlord situation. He’s—I don’t know why he keep doing that.

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

We’re looking at a court order right here. So you went to court and they gave a ruling but they didn’t give you any paper before you left?

JUNE ROBINSON:

No. They did a Zoom thing. No.

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

Oh, you did a Zoom thing?

JUNE ROBINSON:

Yeah.

DETECTIVE TOONE:

The reason why we were trying to get in contact with you is to help you along with the process. Because we knew a certain date that was set, there’s nothing we can do at that time. We were trying to help you to try to see if you can go back down to the court or do anything, because once our hands are tied, there’s nothing we can do. And that’s why we came back here multiple times, putting multiple letters on your door with the number to contact us, because the only person that you need to speak with is a judge. If the judge signs an order, that’s all you have to do is go see the judge. We have no control of that. He signed the order.

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

I don’t have that power, OK? You have to talk to a judge. Someone over me that supersedes me, tells me what to do.

JUNE ROBINSON:

So you’re telling me I’m going to get locked out of my apartment?

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

Well, as of—

JUNE ROBINSON:

Me and my 11-year-old daughter?

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

I don’t—I don’t see—

DETECTIVE TOONE:

If we don’t do it today, we will be doing it next week. We will be doing it next week. So whatever affairs you need, have it in order by that date. Because we will be coming back. We will be posting it on the door.

JUNE ROBINSON:

I understand that.

DETECTIVE TOONE:

So the next time we come, there shouldn’t be an issue, right?

JUNE ROBINSON:

What’s your name?

DETECTIVE TOONE:

Detective Toone.

JUNE ROBINSON:

Wait, detective who?

DETECTIVE TOONE:

Toone, T-O-O-N-E. We still working with you.

JUNE ROBINSON:

And I appreciate that.

DETECTIVE TOONE:

We’re doing anything we can. But what I’m telling you, once I get another date, that is it. All right? So we’re going to call—they’re not here, so we’re going to have to move forward. But like I said, we will be back to talk to you, and I will call you and let you know if I’m going to post it and everything.

JUNE ROBINSON:

Thank you, thank you. Thank you, thank you. Thank God, [inaudible] blessing.

DETECTIVE BLAKE:

All right. Have a good day.

JUNE ROBINSON:

You, too.

EMILY BENFER:

Housing is foundational. It’s a pillar of resiliency in the same way that employment and education are. But if you knock out that one pillar, housing, where you live, your home, you can’t access any of the others.

California

MALE NEWSREADER:

Tenants are protected during the pandemic. They don’t have to pay the rent and their landlords can’t evict them.

NARRATOR:

While almost every state—and many cities—passed their own eviction moratoriums, California had the longest running ban.

MALE NEWSREADER:

Small landlords say they simply can’t afford to house people for free.

NARRATOR:

In Los Angeles, Dyan Golden said her upstairs tenant stopped paying rent.

DYAN GOLDEN, Los Angeles landlord:

When the pandemic first happened in March, I was like everybody else. Like, what does this mean? And as far as being a landlord, I didn’t project or see anything. I didn’t put anything together in terms of eviction moratorium. What is that? I mean, none of that came to mind.

And matter of fact, the first month that my tenant didn’t pay, I think it was in March. And I told him, I said, you know, if I were working, I wouldn’t either, because everything’s just so uncertain. Next month, he paid. And then he skipped again. No problem; I trusted him. I figured he’ll pay me back. I didn’t know if or when my tenant was going to pay rent. So it’s like having your hands tied behind your back and someone can just take and do whatever with your life, with your livelihood.

There’s so many people that think that landlords are bad. That landlords are rich. They have a lot of money. That landlords should not make a profit. That it’s not a business. And that’s why we’re the scapegoats. In the end, I lost 11 months’ rental income. I have to eat. I have to get my medicines. Plus, now I’ve got legal bills because I need an attorney to know, how do you evict somebody? What do I do?

NARRATOR:

As the pandemic stretched on, tenants were falling deeper and deeper into debt.

TERESA TRABUCCO, Riverside County tenant:

When the schools shut down, this is when it all started for me. My son was no longer to attend in-person schooling. And that’s where I was unable to work during the week because now I’m staying home and doing the home-schooling. And our restaurant went down to take-out only.

Since this, it’s been a journey. It’s been an emotional roller coaster. Since September, I have not paid my rent, so I’m looking at eviction if I don’t have 25% of my rent paid. But even if I do have that part paid, I’m still going to owe about $7,500. So where’s that going to come from?

Every couple months I get notices on my door from the apartment complex letting me know the balance of what I owe at that time, and every time that hits my door, it just brings me to another place. And I just—I cry because just seeing that rack up is just difficult, because I don’t know how I’m going to get out of it. [Cries]

This apartment means a lot to me. It’s our safe haven. It’s something that I’ve worked so hard to keep and provide for us. So it’s just not an apartment. It’s our home.

NARRATOR:

To help tenants like Teresa Trabucco who were behind on their rent, Congress had allocated billions of dollars—one of the largest such efforts in history.

EMILY BENFER:

Congress passed federal rental assistance and that ended up amounting to over $46 billion, which was the amount the landlord associations and apartment associations said they needed to make themselves whole.

NARRATOR:

The program was meant to provide rental relief payments to tenants and landlords and cover back rent, late fees and utility costs.

EMILY BENFER:

The same way that we’ve never had a moratorium before, we have never had the national infrastructure for rental assistance. So states were ill-equipped to actually disperse it to communities. In fact, by the end of June 2021, only $3 billion of $46.5 billion had been distributed to the landlords who needed it and to prevent the housing displacement of those millions of tenants.

RICH KISSEL, Los Angeles landlord:

See you, guys.

We had three tenants that stopped paying altogether, and it became quite a burden now, because we’re talking about 10 months, 11 months later now, and the tenants owe me $39,000 and change. And that’s a very large sum of money that affects everything about the building.

In California, although the governor has proclaimed that there’s rent relief and rent relief is coming, and we’ve had to apply, and we’ve applied for the three tenants, but unfortunately, due to some of the administrative difficulties in complying with the application process, the money still have not come through.

TERESA TRABUCCO:

I applied for several different rental assistance programs throughout Riverside County, and each program, I felt like it was just a dead end. They kept referring me to another place. And then the apartment manager submitted the paperwork for me to get started on the rental assistance program. And two weeks went by. No check. Third week, I’m like, OK, it’s been 15 business days, still no check. I was like, it’s one hurdle after another. I’m like, it’s not going to come through.

The options I’m thinking about would be possibly to move in with my sister and rent a room from her, or my parents. Move back in with them. But you know, at 43 years old, you shouldn’t have to be going back to live with your parents or struggling to find somewhere to live or if you’re going to live on the streets.

NARRATOR:

Alexys Hatcher had also applied for the rental assistance, but the money hadn’t come through before she was evicted.

Like many states, Texas had enlisted charitable groups such as the Salvation Army to help distribute the funds.

JANEEN SMITH, The Salvation Army:

I first met Alexys, my supervisor called me and said that she had watched a story on the news about a young lady who had been evicted from her home, and she was a single mom with a little girl.

I think I was mad and I was frustrated because I know that evictions weren’t supposed to be happening.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Yay!

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Yay!

JANEEN SMITH:

And how do you explain that to your child? So her story touched me on different forefronts: being a case manager, being a mom and just being a person.

My department handles court-ordered evictions. So we pay rent. Now we’re paying mortgages. We’re just trying to make sure that anyone who needs the assistance is able to stay in their home. I am preventing clients from entering into a shelter or sleeping in a car or having to go and couch surf or check into a hotel. So we are trying to divert them from being at risk of homelessness.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Do you like this one better?

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Yeah!

ALEXYS HATCHER:

OK, so guess what? We’re going to go buy groceries, because guess what?

JANEEN SMITH:

One thing that really sticks out was that she told me her daughter asked what was going on, and she told her that their house was broken and that they had to find a new house.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Nice and lovely!

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Nice and lovely.

JANEEN SMITH:

She didn’t want to tell her baby that they were being evicted and so she just told her that the house is broken, we’re going to find another house and it’s an adventure. And I just think the way she handled it with her daughter—I don’t think children should have to worry about where they’re going to sleep. Never. Or what they’re going to eat.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Spaghetti? No. Come on. We have to get veggies, too. Do you want corn or green beans?

Since I’ve been grocery shopping, it’s about maybe three weeks. But since all of my food ended up in black bags and I had to throw away a lot of it, this is exciting. So even though I’m in the hotel, the fact that I can go buy groceries, I can cook, there’s pots and pans, our dishwasher. It gives me a sense of just being normal. I don’t feel like I’m not in my home.

It makes me happy. I don’t feel like I’m just failing. I feel like I’m doing something that is normal. Here you go. Would you like to sit in the chair and have it? Or would you like to sit at the desk? OK.

NARRATOR:

Janeen Smith started working with Hatcher to find her a new place to live and to get the rental assistance money.

JANEEN SMITH:

I think with Alexys, the difference between her and a lot of clients, she is very organized, and anything that I asked her for, she had it. “Ms. Smith, I got records. Ms. Smith, do you want me to drop it off? You want me to email it to you?” She was on top of it.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi, Erin. I was wondering if y’all had any two-bedrooms available? Aw. Do you know when you will have something?

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

To leave a message for the office or leasing, please press one.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi, my name is Alexys Hatcher. I was looking to move into your two-bedroom townhome, kind of immediately.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

Thank you for calling [inaudible].

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Hi, I was wondering if you guys had any two-bedrooms available?

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

I will have something for—

JANEEN SMITH:

It was important that she picked a place that she wanted to be in. Don’t just get something and not want to be there. Take your time, look at it. There’s a lot of resources out there, but if you don’t know or have someone to tell you, then you don’t get the help.

TERESA TRABUCCO:

Hi, Randy, how are you? Good.

I don’t like to ask for help. So, I struggled with that. It wasn’t a good feeling. The management company, they really kept on top of everything with me, keeping me informed. I think they were rooting for me. Within I would say about 6-8 weeks, I heard back from them. On a Sunday night, I got that email, half-tired, and I’m reading it. And I just sat there and I’m like, what? What? Like, this is not—I’m seeing too many numbers there. It covered all of my past due rent and three months advanced rent. And my water and sewer and trash was paid. It just felt like a ton of bricks just came off of my shoulders. And it was like, I wasn’t losing my home and Liam and I had a place to stay. [Cries] So, it was such a good feeling.

NARRATOR:

Of all the states, California received the most federal rental relief—more than $5 billion.

Dyan Golden and many other landlords ended up receiving money for the rent they missed.

Across the country, the money was eventually distributed to millions of people.

EMILY BENFER:

It supported people at a time of extreme crisis. It made it possible for them to go back to work and prevented the poor health, the anxiety, the mental health breaks that are associated with eviction.

NARRATOR:

Emily Benfer went on to work for the White House, helping implement the rental relief plan.

EMILY BENFER:

The communities that were able to distribute rental assistance had lower displacement rates. They had lower filing rates in eviction courts. So all of these interventions, these measures, they’re important and they matter.

NARRATOR:

Alexys Hatcher’s rental assistance money came through and ended up helping her pay for a new apartment.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

That one was full of clothes.

Today is moving day, yes. It’s really exciting, even though I’m probably going to be really exhausted by the end of the day, it’ll be worth it because we’re not in a hotel or at my grandma’s house.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Mommy, look what I found!

ALEXYS HATCHER:

What’d you find?

ALIYAH HATCHER:

This is from my—

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Bubble blower?

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Yeah! And it’s on my Minnie Mouse one!

ALEXYS HATCHER:

It is? All right.

UNCLE:

Watch out, baby.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

We’ve started to kind of go through all of our stuff because those black bags, they were all mixed up. I couldn’t find everything. This is definitely not the way it should be done, especially the way the things are in the bag. It’s just like throwing all your things out like trash. I know it’s kind of funny, but—I mean, it’s funny now. It was not funny the day I thought about it.

Get some toys for me Liyah, please. This bag is full of Christmas decorations. And a Monopoly game.

I don’t know. Pulling my stuff out, it’s like some things have memories, so that’s just like a sense of comfort in itself, is that I’m back with my things.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Now somebody will play with me?

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Just a second. I’ll play with you as soon as I’m done.

MARK MELTON, Alexys Hatcher’s attorney:

To see someone with a support system versus someone without, you shouldn’t be surprised that those are two totally different outcomes. We’ve got other families that are right now living in their car with their two kids. We’ve got other families that we’ve had to put in shelters that are still in shelters. These are the more typical stories when we’re talking about eviction.

NARRATOR:

June Robinson was not able to provide rental receipts or a valid lease to prove she was a legal tenant and was forced to leave the apartment.

In August 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court blocked the federal moratorium on evictions.

FEMALE CONSTABLE:

Constable’s office!

MALE CONSTABLE:

Constable!

NARRATOR:

And state bans have since expired.

In the coming months, the last of the government’s rental relief money is expected to be paid out.

MALE CONSTABLE:

5-21. Go ahead and show me clear set out.

That was a good day. I didn’t have to encounter the tenant being there and seeing the look on their face or anger or whatever the case may have been. It’s kind of heartbreaking at times to do it, but it is part of the job that I signed up to do, so as much as I hate it, I have to do it.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Excuse me, Mommy. I got to make some room for my babies.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

Gracie, sit down and eat your food, please. It’s getting late.

If it was just me by myself, no pandemic, I just got behind on my rent and my landlord decided to evict me, I don’t think anyone would have thought twice about it. They probably would have made assumptions like, “Well, whatever she was doing, that’s her problem.” But I’m kind of glad that it did happen in a pandemic where everyone is thinking about it and talking about it because when this pandemic is over, evictions are not going to stop. There’s still going to be people that are going to need help, regardless of pandemic or not.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

Kiss me and tell me I will never be alone. Kiss me and hug me tight and say, “I love you.” I never will let you go.

ALEXYS HATCHER:

The end.

ALIYAH HATCHER:

I’m gonna let it stay right here so I can read it tomorrow.

WRITTEN AND PRODUCED BY Bonnie Bertram

CO-PRODUCED BY Anne Checler Erik German

SENIOR PRODUCERS Nina Chaudry Frank Koughan

EDITED BY Anne Checler

ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Emily Orr

FIELD PRODUCERS Daniel Casarez Brian Palmer

PRODUCTION MANAGER Victor Couto

CAMERA Alfredo Alcántara Harris Ansari Laura Bustillos Jáquez Ian Cook Liam Dalzell Mike Doyle Jeff Freeman April Kirby Qinling Li Luis Mendoza Hanna Miller Mark Montgomery Rafael Roy Chris Sinclair David Usui Scott Wilson

DRONE OPERATOR Bruno Federico

ONLINE EDITOR/COLORIST Jim Ferguson

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan

POST PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR Cullen Golden

POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Ryan Brown

MEDIA MANAGER Aaron Thomas

GRAPHICS Cullen Golden

ARCHIVAL PRODUCER Rebecca Losick

INTERNS Kirk Cohall Bryana Quintana Chris Vazquez

ENGAGEMENT PRODUCER Isadora Varejão

AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT MANAGER Caroline Watkins

ARCHIVAL MATERIALS Getty Images

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS CBS News KNBC-TV KVUE-TV KXAS-TV The New York TImes PBS NewsHour WBTS-TV WPIX-TV

FOR RETRO REPORT

HEAD OF STRATEGY AND PARTNERSHIPS Colleen McCarthy

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Kyra Darnton

FOUNDER Christopher Buck

Original funding for this program was provided by public television stations, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Abrams Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Park Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, FRONTLINE Journalism Fund with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler through the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen.

Support for Facing Eviction is from the WNET Group’s Chasing the Dream initiative on poverty and opportunity in America with major funding by The JPB Foundation. And additional funding by The Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III.

And additional support for Facing Eviction to Retro Report by: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Economic Hardship Reporting Project, Pulitzer Center.

FOR FRONTLINE

DIRECTOR OF POST PRODUCTION Megan McGough Christian

SENIOR EDITOR Barry Clegg

EDITOR Brenna Verre

EDITOR Joey Mullin

ASSISTANT EDITORS Alex LaGore Tim Meagher Christine Giordano

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Stevie Jones

FOR GBH OUTPOST EDITOR Deb Holland

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY Tim Mangini

INTERNS Joe Adams Naomi Birenbaum Haley Fuller Caroline Rangel Gomes Catherine Hurley Cara Stiegler

FRONTLINE / EMMA BOWEN FELLOW Sharon Boateng

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Will Farrell

DIRECTOR OF IMPACT AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS Erika Howard

DIGITAL WRITER & AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIST Patrice Taddonio

AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT EDITOR Ambika Kandasamy

ASSISTANT EDITOR, DIGITAL Tessa Maguire

MANAGER, PUBLIC RELATIONS AND COMMUNICATIONS Anne Husted

PODCAST PRODUCER Emily Pisacreta

ARCHIVE & RIGHTS CONSULTANT Kevina Tidwell

ARCHIVES & RIGHTS MANAGER John Campopiano

FOR GBH LEGAL Eric Brass Suzy Carrington Jay Fialkov

SENIOR CONTRACTS MANAGER Gianna DeGiulio

BUSINESS MANAGER Sue Tufts

BUSINESS DIRECTOR Mary Sullivan

SENIOR DEVELOPER Anthony DeLorenzo

LEAD DESIGNER FOR DIGITAL Dan Nolan

FRONTLINE/COLUMBIA JOURNALISM SCHOOL FELLOWSHIPS TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Chantelle Lee

ABRAMS JOURNALISM FELLOW Aasma Mojiz

FRONTLINE/NEWMARK JOURNALISM SCHOOL AT CUNY FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Bruce Gil

FRONTLINE/FIRELIGHT INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM FELLOWS Cristina Ibarra Ursula Liang

DIGITAL REPORTER Paula Moura

EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Lauren Prestileo Callie T. Wiser

DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Miles Alvord

HOLLYHOCK FILMMAKER IN RESIDENCE Marcia Robiou

SERIES PRODUCER AND EDITOR Michelle Mizner

INVESTIGATIVE PRODUCER Daffodil J. Altan

DEPUTY DIGITAL EDITOR Priyanka Boghani

DIGITAL EDITOR Jennifer Wehunt

EDITORIAL COORDINATING PRODUCER Katherine Griwert

POST COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITOR AT LARGE Louis Wiley Jr.

FOUNDER David Fanning

SPECIAL COUNSEL Dale Cohen

DIRECTOR OF AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT Maria Diokno

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Frank Koughan

SENIOR PRODUCER, SPECIAL PROJECTS & INNOVATION Carla Borrás

SENIOR EDITOR & DIRECTOR, LOCAL JOURNALISM Erin Texeira

SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER Nina Chaudry

SENIOR EDITOR INVESTIGATIONS Lauren Ezell Kinlaw

MANAGING DIRECTOR Janice Hui

MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Metz

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Raney Aronson-Rath

A FRONTLINE production with Retro Report

©2022 WGBH Educational Foundation and RetroReport, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

FRONTLINE is a production of GBH which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.