|

|

|

|

Lighting technician Cecilia Krigge spotlights for

leopard in the African night.

Lighting technician Cecilia Krigge spotlights for

leopard in the African night.

|

Behind the Scenes

by Peter Tyson

If you think filming leopards at night is difficult, you're

right. At the same time, you have no idea. Amanda Barrett and

Owen Newman, producers of

Leopards of the Night,

and their team spent more than 3,300 hours over the course of

three years shooting the film on location in Zambia and

Namibia. It was the hardest film either has ever made, they

say. Here's why:

The workday began around four o'clock in the afternoon. That's

when the film crew headed out into the bush in two cars. (One

held Barrett and Newman with the cameras, the other bore the

infrared lights and lighting technicians Vernon Bailie and

Cecilia Krigge.) The going was extremely rough. Foot- and

hoofprints that elephants and other large animals leave in the

wet mud of the rainy season dry out, forming concrete-hard

holes during the June to October dry season, when the team

filmed. "Leopards just glided over those holes, but it was

very bumpy for the cars," says Owen Newman, who was cameraman

as well.

The film crew's lighting car sticks to the heels of a

roaming leopard.

The film crew's lighting car sticks to the heels of a

roaming leopard.

|

|

The first order of business was to find a leopard. That often

meant hours of searching for eyeshine with white spotlights

and listening for the alarm calls of impala and other prey.

Many nights passed when they never even laid eyes on a

leopard. When they did, they had to bring the cars close

without disturbing either the leopard or its prey. Once in

position, hours might pass before something filmable happened.

And it was cold: while the days were scorching, nights were

chilly enough to require scarves, hats, even mittens.

Typically the team stayed out all night, only turning back

about four in the morning. Sometimes it was longer. Once they

spent 56 hours straight in the car, waiting for a leopard to

return to a kill it had placed up a tree. "For all that

effort, sitting in the sun all day and no sleep, we used about

two shots," Barrett chuckles. In the end, they averaged one

good filming night every three weeks.

|

Night goggles offer lighting technician Vernon Bailie

a window into the night.

Night goggles offer lighting technician Vernon Bailie

a window into the night.

|

Filming at night also engendered many technical challenges.

The team brought along a Sony 7000 film camera for shooting in

low-light conditions, such as moonlight. But they had

discovered during an earlier film project that leopards

typically only hunt in pitch dark; if the moon is out, the

cats will wait for it to slip behind clouds before they make

their move. So, in a first in natural-history filmmaking in

Africa, Newman turned to infrared cameras. He used either a

Baxall or Cohu standard night security camera. Sensitive to

infrared light, which the team provided via special infrared

lights that Bailie aimed off the back of the lighting car,

these cameras can film in total darkness (see

The Camera That Caught a Leopard).

Since they were working with technology that no one had ever

used in that kind of situation before, they had to learn as

they went along, Barrett says. For one thing, neither infrared

camera had a viewfinder. So Newman, perched in the back of the

camera car, had to fly by the seat of his pants, as it were.

First, he took cues from Barrett, who sat up front wearing a

pair of night-vision goggles. While these devices, which

provide a grainy, bright-green view and are "a bit like

looking through very bad eyeglasses," Barrett says, they

allowed her to pick out leopards and other wildlife in the

darkness. She then described to Newman where to aim his

camera. "I would say something like, 'The leopard is at three

o'clock, about 25 meters away, crouched down by a patch of

grass,'" Barrett says.

Focusing a long-focal-length lens on a moving leopard

was a daunting challenge.

Focusing a long-focal-length lens on a moving leopard

was a daunting challenge.

|

|

Newman then aimed his camera in that direction and watched a

nine-inch, black-and-white monitor to see what he was picking

up. But whenever he used a large lens, such as a 300 mm, the

depth of field was so shallow that he often missed his target

even when he was looking right at it. "I could be looking at

blades of grass, and the leopard could be six inches behind or

in front of that and I wouldn't see it on the monitor because

it was so out of focus," Newman recalls. "I would be swinging

the lens around and changing focus all the time. It was very

frustrating, especially when the leopards were stalking."

As if filming weren't challenging enough, Newman constantly

had to switch between the low-light and infrared cameras and

their respective lighting systems, depending on what the

leopard was up to. He did that in the pitch dark, up to 12

times in a night. "He got it down to seconds," Barrett says,

"but you'd only need one thing to go wrong, and you'd have

lost a filming opportunity that might have taken three weeks

to present itself." And things went wrong a lot, because

traveling over the uneven ground meant that cables and other

connections were regularly shaken loose.

|

Even a pestering insect cannot disturb the exquisite

concentration of a stalking leopard.

Even a pestering insect cannot disturb the exquisite

concentration of a stalking leopard.

View

clip of leopard stalking:

RealVideo:

dialup

|

broadband

Quicktime:

757K

AVI:

757K

You'll need either the free

RealPlayer software, or free

QuickTime software

to be able to view this clip. If you already have

the software, choose the appropriate connection

speed/file size to view a clip.

|

Even when Newman had successfully zeroed in on a leopard, he

was at the mercy of the leopard's own unpredictable behavior.

"Compared to cheetahs and lions, leopards are very, very smart

hunters," Barrett says. "They'll try one way, then they'll

change their minds, double back, go all the way around the

target animal in a big detour, and try it from the other side.

We would have to move with the leopard, without upsetting

either the prey or the leopard." She laughs. "We'd get all the

way there, and then she'd change her mind again and try

another angle."

They also had to be on their guard against the leopards

themselves. While the cats largely ignored them, the film crew

could never forget that these were wild animals. "Once we were

just below a male leopard that had killed a baboon and was

eating it in a tree," Newman recalls. "He got a bone stuck in

his cheek and couldn't get it out. After that he became quite

aggressive, thrashing his tail from side to side and getting

angry with himself. We decided to back away from that."

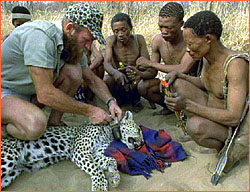

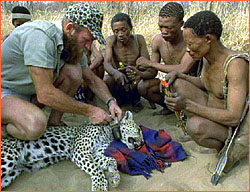

Leopard researcher Philip Stander and his Bushmen

colleagues adjust the radio collar of a tranquilized

leopard in Namibia.

Leopard researcher Philip Stander and his Bushmen

colleagues adjust the radio collar of a tranquilized

leopard in Namibia.

|

|

Leopards were not the only creatures to be wary of. Once,

while filming a pride of lions vying with crocodiles over an

antelope kill, the team lost track of the lions in the pitch

darkness. "We had five lions behind the car, about three in

front, and one by the side," Barrett remembers. "Then a couple

started mating. Bear in mind we were in a completely open

vehicle. We didn't know if one by accident might jump into the

car to get away from a crocodile or another lion. That made us

sit up and concentrate." Most dangerous of all, it turns out,

was the mosquito. During the filming, both Barrett and Newman

came down with cerebral malaria. In fact, the disease caused

Newman, who suffered two debilitating bouts, to sit out the

only night he missed in ten solid months of filming.

Despite the myriad difficulties associated with making the

film, there were substantial rewards. For Newman, it was the

chance to be out all night in the African bush, with myriad

insect and bird sounds and various plants coming into flower.

("As you moved through the park," he says, "you could

sometimes tell where you were just by the flower smell.")

Barrett particularly appreciated working with the Bushmen.

"They were so much in their element in the desert, whereas we

were staggering around hot, sweaty, clutching water bottles,"

she recalls. "We wouldn't have lasted a second if they had

left us."

|

"His sleek fur reflected different shades of apricot

and chestnut in the sunlight."

"His sleek fur reflected different shades of apricot

and chestnut in the sunlight."

|

Most rewarding, of course, were the leopards. The team filmed

leopard behavior never before seen, including the supreme

concentration the cats hold while stalking prey in the pitch

dark, and the surprising fact that a leopard—usually the

most silent of stalkers—will sometimes deliberately

stamp the ground with its foot to disorient prey. For Barrett,

the most fulfilling moment of all came one afternoon when a

male leopard they'd been working with for three days and

nights sauntered over to sleep in the shade of the car. "He

had just killed and was full of food, and he was very relaxed

with us because we hadn't done anything to upset him," she

says. "We could hear him snoring. He was in the peak of

condition, with a thick, muscular neck and his sleek fur

reflecting different shades of apricot and chestnut in the

sunlight. Beautiful animal."

Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA.

Night Vision

|

Camera that Caught a Leopard

Behind the Scenes

|

Seeing through Camouflage

Resources |

Transcript

| Site Map |

Leopards Home

Editor's Picks

|

Previous Sites

|

Join Us/E-mail

|

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated November 2000

|

|

|

Lighting technician Cecilia Krigge spotlights for

leopard in the African night.

Lighting technician Cecilia Krigge spotlights for

leopard in the African night.

The film crew's lighting car sticks to the heels of a

roaming leopard.

The film crew's lighting car sticks to the heels of a

roaming leopard.

Night goggles offer lighting technician Vernon Bailie

a window into the night.

Night goggles offer lighting technician Vernon Bailie

a window into the night.

Focusing a long-focal-length lens on a moving leopard

was a daunting challenge.

Focusing a long-focal-length lens on a moving leopard

was a daunting challenge.

Even a pestering insect cannot disturb the exquisite

concentration of a stalking leopard.

Even a pestering insect cannot disturb the exquisite

concentration of a stalking leopard.  Leopard researcher Philip Stander and his Bushmen

colleagues adjust the radio collar of a tranquilized

leopard in Namibia.

Leopard researcher Philip Stander and his Bushmen

colleagues adjust the radio collar of a tranquilized

leopard in Namibia.

"His sleek fur reflected different shades of apricot

and chestnut in the sunlight."

"His sleek fur reflected different shades of apricot

and chestnut in the sunlight."