|

|

|

(back to Life on a Submarine) I would recommend that anybody who wanted to try the submarine service do so. If it's not suited for you, you'll find out long before you go to sea on a submarine. In the first place, they give you a serious battery of tests to see if you are suited for the submarine service, and I can say without any qualms that the Navy has excellent psychological exams. They will weed you out in a big hurry. If they think you're suited, they'll send you to submarine school in New London, Connecticut. That school might run for 12 to 14 weeks, every day from 5 a.m. to late at night, and they'll teach you submarines inside and out. Now, say there are 50 guys in your class. Before that 12 or 14 weeks are up, maybe 50 percent of those people will be gone. They'll find that it's just not for them. I graduated in Class Number 116, and we had 22 graduates.

To qualify in my day, you would have to learn every job on that ship. [Editor's note: The same holds true today.] I don't care whose job it was: the diving officer's, the electrician's, the radioman's, the engineman's, the torpedoman's job—you would have to learn every single system. Let's say I went into the engine room. There's a distilling plant there that converts saltwater into freshwater. I would have to learn how that device works, what each valve did. When I thought I had that memorized pretty well and could draw that system on a piece of paper, I would go to a qualified submariner, an enlisted man, and tell him I wanted to get checked off on that item. We had a qualification card that had to be signed off by four people. The first person to sign you off was an enlisted man who was qualified. (Qualified personnel are the only ones who can sign the card off; even officers who are qualifying have to be qualified first by an enlisted man.) Once I could operate and draw that system to the satisfaction of the qualified submariner, he would sign me off. Then I would go to the division officer, and he would take me through everything. He would say, "I want you to draw the freshwater system. I want you to draw the high-pressure accumulated air system. How do you start the engine? How do you do this, how do you do that?" When he was satisfied that I knew it well enough, he would sign me off. On your final qualification, the Captain and Executive Officer would take you through the boat. Once they signed you off, you were qualified, you received your coveted Dolphins, and immediately after you were dismissed from quarters, somebody would grab you, and you'd be duly tossed overboard as a rite of passage. You were now a Submariner. —Tippy "Salty" D'Auria was an electrician aboard the USS Trumpetfish (SS-425), a diesel-electric attack submarine, from 1954 to 1958. He lives in Miami, Florida. Continue: Paul Benton

See Inside a Submarine | Can I Borrow Your Sub? Sounds Underwater | Life on a Submarine Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Submarines Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule | About NOVA Watch NOVAs online | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Search | To Print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated May 2002 |

Tippy D'Auria

Tippy D'Auria

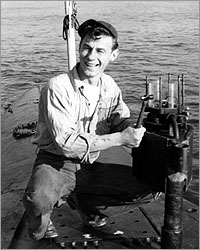

Tippy D'Auria working on the stern light of the USS

Trumpetfish in 1956.

Tippy D'Auria working on the stern light of the USS

Trumpetfish in 1956.