|

|

|

After the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz killed more than 23,000 people in Colombia in 1985, the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance asked the U.S. Geological Survey to design a program to help foreign governments cope with volcano crises. The result was the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program, or VDAP. Based at the Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington, this crack unit is standing by at all times, ready to lend a hand at the next volcano showing signs of blowing up. NOVA asked VDAP's chief, volcanologist Dan Miller, what it's like to be on the team. NOVA: What do you consider VDAP's greatest success?

Miller: Without a doubt the 1991 eruption of Mt.

Pinatubo in the Philippines, which was the third-largest

eruption of this century. When unrest began, VDAP's little

team of eight people, augmented by other scientists from the

U.S. Geological Survey and using funding and support from

the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, were invited

to join scientists from the Philippine Institute of

Volcanology and Seismology. We worked together to install

VDAP monitoring equipment to build a volcano observatory on

very short notice. Data from the instruments were

telemetered back to a location on Clark Air Base, which is

very close to Pinatubo.

In the end, Philippine officials evacuated about a million people from around the volcano. About 70,000 of those people lived in villages that were totally destroyed a few days after they left. So literally tens of thousands of lives were saved, not to mention hundreds of millions of dollars worth of military equipment, which was moved out of harm's way. NOVA: When an eruption occurs, do you custom design a team and the equipment you'll send?

Miller: Absolutely. When unrest begins at a volcano,

we always wait for an official invitation, which usually

comes through the State Department or the U.S. Agency for

International Development. We think about the volcano and

what kind of eruptions have occurred there in the past. Then

we select a team of scientists with the kind of expertise

that is requested and required, and we take the kinds of

equipment with us that will help out.

NOVA: You just returned from a crisis in Ecuador. What was that like? Miller: There's an explosive volcano by the name of Guagua Pichincha that lies about six miles west of Quito, the Ecuadoran capital. Now, Quito has a population of 1.8 million, and this 15,800-foot volcano has had several periods of restlessness involving steam explosions and earthquakes. The most recent one began with a series of steam explosions on August 7th. More than 50 explosions have occurred since, and there has also been seismicity. The local scientific team, which has been monitoring volcanos in Ecuador for about two decades, requested assistance from VDAP. About a month ago we sent a team of four scientists to Ecuador to provide assistance. Our purpose is to maintain a low profile, to provide assistance to the local scientific team, and to help them to understand what's happening so that they can communicate that information to public officials and civil defense organizations. After we arrived, we spent time in the field with our colleagues, installing new equipment and getting the data telemetered back to their observatory. The restlessness is continuing as we speak. There are daily explosions at the summit and various types of seismic activity. It's too early to tell whether or not it will erupt.

NOVA: Would you go back down if they called you back?

NOVA: What equipment do you bring along? Miller: We have three complete volcano observatories sitting on the shelf ready to go right now—two for international use and one for domestic use. They include three primary tools with which to forecast volcanic eruptions. First, a telemetered volcanic seismic monitoring network to detect the earthquakes that often precede eruptions. Second, tiltmeters and electronic distance measuring networks to monitor bulging or deformation that results from magma pushing up against the solid rock of the volcano. Finally, devices to measure sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide. These two diagnostic gases associated with magma are fairly easy to detect. When the flux of these gases at the surface increases with time, we become concerned about magma rising close to the surface and about the increased likelihood of an eruption. (For more details on techniques and equipment, see Can We Predict Eruptions?)

NOVA: How much equipment do you bring?

The equipment is modular, and so each of these trunks weighed less than 70 pounds, which is the maximum amount that you can ship as excess baggage. But each had a solar panel, batteries, and either a tiltmeter or a seismometer as well as all of the cabling and radios. All 38 trunks were flown on commercial airliners to Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, where they were put on a military C-130 and flown into a little airstrip near Rabaul. From there they were carried by truck to the Rabaul Volcano Observatory, then flown out by helicopter in modules to the field sites and installed.

NOVA: The VDAP team was right on the volcano during

the eruption?

NOVA: How soon after the team left did it erupt? Miller: Four days. Actually, the big eruption occurred then. There were dangerous eruptions occurring everyday, even when that decision was made. So we try to do things in as safe a way as possible. But it's always difficult to anticipate what a volcano will do. Each is different, each has a unique plumbing system. NOVA: Eruption prediction is an inexact science. How soon might it approach an exact one? Miller: It's very frustrating that, even with equipment installed and the most experienced team members that we can assemble, it's extremely difficult to accurately forecast exactly what the volcano is going to do, when it's going to do it, and how big an eruption there will be. Part of the frustration is that scientists don't make decisions about land use, or how to respond to the unrest, or whether or not to evacuate. That's the reponsibility of civil defense and elected officials. But these are life-and-death decisions, and they have huge political and economic consequences.

When will forecasting get better? It's improving year by year. Every time we work on a volcano crisis, we learn more about how to interpret the subtle and sometimes very sophisticated signals that volcanoes give as magma moves around. There are a whole suite of different kinds of earthquakes, for instance: volcano tectonic earthquakes, long-period earthquakes, volcanic tremor. It's a very, very complicated business. However, compared to earthquake predictions, we're extremely lucky; no one has any ability to forecast earthquakes. NOVA: I've read that you don't think of yourselves as "cowboys," despite the risks you're taking.

NOVA: Ever had any close calls yourself?

Miller: I'm a pretty cautious person. I worked at Mt.

St. Helens for years before the 1980 eruption, for seven or

eight months during that year, and off and on ever since.

But when the volcano was erupting, and when it was restless

between eruptions, I was pretty darn careful. I spent very,

very little time up in the crater, because it was quite a

dangerous place because of rock falls off the crater rim and

explosions on the dome. When I worked all over the blast

zone in the summer of 1980, I and my colleagues were always

pretty close to the helicopter, ready to start it up and

leave at a moment's notice.

Planning for Disaster | Resources | Teacher's Guide Transcript | Printable page | Site Map | Vesuvius Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

VDAP personnel unload volcano monitoring equipment at

Mt. Pinatubo, Philippines, June 1991.

VDAP personnel unload volcano monitoring equipment at

Mt. Pinatubo, Philippines, June 1991.

Damage from lahars, or volcanic mudflows, at

Pinatubo.

Damage from lahars, or volcanic mudflows, at

Pinatubo.

Installing volcano monitoring equipment at Mt.

Pinatubo.

Installing volcano monitoring equipment at Mt.

Pinatubo.

VDAP team member Andy Lockhart in action at Mt.

Pinatubo, June 1991.

VDAP team member Andy Lockhart in action at Mt.

Pinatubo, June 1991.

Loading VDAP equipment onto a C-130 in Port Moresby,

Papua New Guinea, September 1994.

Loading VDAP equipment onto a C-130 in Port Moresby,

Papua New Guinea, September 1994.

Phreatic or explosive steam venting high on Mt.

Pinatubo after the June 1991 eruption.

Phreatic or explosive steam venting high on Mt.

Pinatubo after the June 1991 eruption.

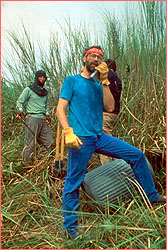

VDAP and local scientists install a tiltmeter at

Soufriere Hills volcano, Montserrat, August 1995.

VDAP and local scientists install a tiltmeter at

Soufriere Hills volcano, Montserrat, August 1995.

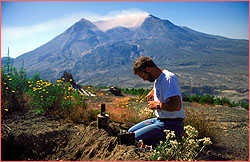

VDAP staffer Andy Lockhart sets up a seismometer

within sight of Mt. St. Helens, September 1992.

VDAP staffer Andy Lockhart sets up a seismometer

within sight of Mt. St. Helens, September 1992.