Author Archives: Christina Knight

Who Were the African Americans in the Kennedy Administration?

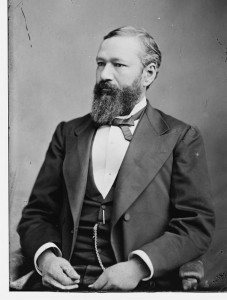

Andrew T. Hatcher, associate White House press secretary, the first black man to hold the No. 2 communications spot in the White House, behind his longtime political compatriot, Pierre Salinger. Photo by Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library And Museum, Boston.

“I regard the death of President Kennedy as the greatest tragedy that has befallen America since the assassination of Civil War President Abraham Lincoln,” declared a grief-stricken John H. Sengstacke, publisher of the Chicago Defender, hours after the 35th president was gunned down at 46 while riding in an open limousine beside the first lady. John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas happened 50 years ago this Friday. Speaking to his black readership, Sengstacke added, “Kennedy’s tragic ending is [also] the greatest blow that the Negro people has sustained since the demise of the great Emancipator.”

Jackie Robinson, the first black major-leaguer and a proud Republican who had supported Richard Nixon for president in 1960, contributed to the outpouring. “It’s hard for any of us to imagine even the tragedy that has hit,” he was quoted in the Defender. Drawing a parallel to black civil rights leader Medgar Evers, who had only been shot and killed outside his Mississippi home the previous June, Robinson noted, “Each of these gentlemen … desired a better America,” and even if Kennedy had “needed prodding” in advancing civil rights, “we all admired and respected him.”

Striking to me in going back to the immediate coverage of the Kennedy assassination is how quickly African Americans elevated him to sainthood. Just a few months prior, he had been lukewarm on the March on Washington (worried as he was about a backlash against the civil rights bill he had, at last, proposed in a televised address from the Oval Office on June 11 after sending in the National Guard to carry out a federal court-order desegregating the University of Alabama). Perhaps that sense of nuance—of distinctions among events so close in time—is what comes with the advance of years between my hearing the devastating news as a 13-year-old student in Mrs. Houchins’ geography class in Piedmont, W.V., and reflecting on it as a professor of 63 who has just completed a six-hour series for PBS on the 500-year history of the African American people, (Much of that history was spent making do while waiting for lawmakers to act, as you will see in Episode 5, covering the civil rights movement. It airs tomorrow night and is fittingly titled “Rise!”)

Don’t get me wrong: JFK is one of my favorite presidents. Yet I, like many, am aware of how much he evolved on civil rights, at least when it came to confronting the Southern Democrats in his party in the House and Senate.

“To some, he was slow to begin on his promise when he took office,” George Barbour wrote in the Pittsburgh Courier five days after the slain president had been buried in Arlington National Cemetery, the same cemetery in which Medgar Evers was buried. “However, to this reporter,” Barbour added, “he [JFK] never wavered and in appointments, speeches, application of presidential power, secured direct benefits for the Negro unparalleled in modern history, and this strengthened the character of a great country.” JFK was, if anything, a Cold Warrior aware of America’s standing in the world, of the need to lead “a new generation of Americans” toward what he famously called “the New Frontier.” But another Lincoln?

Indeed, Enoc Waters wrote in the Philadelphia Tribune on Nov. 26, 1963, “In spite of occasional criticism of his civil rights actions and legislative proposals, the thirty-fifth President of the United States was held in warm affection by all Negroes” (despite the fact that, on the day of his assassination, black Republicans were gathered in Cleveland for a political strategy session) so that the only presidents who could be fairly be compared to him were “Lincoln” and that other monogrammed man, “FDR.” The great civil rights attorney Constance Baker Motley agreed, telling the National Council of Women of the United States on Dec. 1, 1963, according to the Atlanta Daily World: JFK was “the greatest presidential advocate of equal rights this century has heard,” and there was only a century exactly separating his murder and the original Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln had issued before his assassination at the climax of the Civil War.

The mourning rites of those four November days in 1963—the shock, the arrival of the body in Washington, the lying in state, the Oswald murder, the funeral procession—certainly etched this image of Kennedy as the second coming of Lincoln in American minds. Whereas the late president had complained about the lack of black faces in the U.S. Coast Guard Academy honor guard at his inaugural parade, at his funeral, there were, Dan Day noted in a column appearing in the Philadelphia Tribune on Nov. 26, two “dark-skinned” military personnel in the eight-man detail “clearly in view at all times about the coffin.”

“Clearly in view”—that was the point, I’ve come to realize, the brilliance of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s stagecraft. A noted devotee of Broadway musicals, including Camelot, of course, JFK personally may have opposed discrimination as a moral matter; but, when it came to politics, he was a pragmatist who balanced his cautious legislative approach with a commitment to advance the symbols of desegregation and diversity in and around the White House, his Camelot. Stagecraft was something he, like FDR before him, made part of the modern presidency, and it’s something we take for granted today. On one hand, to keep Southern Democrats like Sen. Richard Russell of Georgia in the fold, he gave in on appointing their judges in the South. At the same time, to keep black voters in the North on his side, he went out of his way to see that talented black professionals, especially black newspapermen, were hired to get the message out to their readers that they—and the message—would be “clearly in view.”

“But the Cake Was Already Made”

The success of JFK’s public relations strategy rested on the abilities of his advisors. They included a few prominent blacks, who charted his segmented outreach efforts. While top Kennedy surrogates soft-pedaled his civil rights record in the South (there were few blacks who could vote there anyway in 1960), these black strategists targeted specific messages to black voters. It was a “strategy of association,” Nicholas Andrew Bryant writes in his valuable 2006 book, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality. The key to their strategy: black talent and a black press committed to showcasing it.

The man the Kennedy team recruited to lead the charge was the long-time former editor of the Chicago Defender, Louis E. Martin, whom the Washington Post once called “ ‘the godfather of black politics.’ ” He was the eventual advisor of three sitting presidents, and a “well-versed representative of the black protest tradition,” with strong ties to labor, as Alex Poinsett writes in his 1997 biography, Walking With the Presidents: Louis Martin and the Rise of Black Political Power.

Back in the 1930s and ‘40s, Martin had helped turn Detroit Democratic in support of FDR’s New Deal as editor of the Michigan Chronicle. In joining the Kennedy campaign, he, along with black Washington attorneys Frank Reeves and Marjorie Lawson, customized JFK’s image for their friends at leading black newspapers across the country. After all, Martin had helped found the National Newspaper Publishers Association in 1940.

It was a two-pronged attack far more sophisticated than the Nixon people had calculated. While Kennedy toned down his message in the mainstream white papers (and had Lyndon Johnson campaign for him in the South), Martin and company amplified JFK’s support of the Democrats’ strong civil rights plank in a series of brilliant advertisements. The campaigns included a Martin favorite, “A Leader in the Tradition of Roosevelt,” as well as a set of side-by-side pictures of JFK and famous black heroes, from Rep. William Dawson of Chicago (his support was vital) to Virginia Battle, the African-American secretary Kennedy had recruited to his Senate campaign in 1952.

In other words, Bryant’s work suggests: Long before the assassination of JFK catapulted him into the pantheon of civil rights leaders, Louis Martin et al. planted the idea in black newspapermen’s minds.

Along the way, Louis Martin (with others) had a hand in persuading candidate Kennedy to place a timely call to Coretta Scott King when her husband Martin was in jail and got New York’s black powerbroker, Rep. Adam Clayton Powell of Harlem, to accept $50,000 in exchange for making pro-Kennedy speeches. The call to Mrs. King was “ ‘the icing on the cake,’ ” Bryant quotes Louis Martin as saying. “‘But the cake was already made.’”

And when it came out of the oven …

Kennedy, in a tight election, won 78 percent of the black vote. Soon after, Martin became deputy chairman of the Democratic National Committee; but really, Bryant writes, Martin was, with his “great savvy in public relations,” Kennedy’s “personal point man on civil rights” (the stage manager of the black Camelot, if you will).

On the eve of the inauguration in Jan. 1961, Martin, with Kennedy’s other point man on civil rights, Harris Wofford (chairman of the subcabinet group on civil rights), lobbied the president-elect to at least include a nod to “human rights … at home and around the world” in the sterling speech Ted Sorenson more famously helped draft. All through the campaign, Kennedy had stressed that his approach to civil rights would flow from executive—more than legislative—action, and now, with Martin’s counsel in casting the players, he was ready to deliver.

The Black New Frontiersman

“ ‘I am not going to promise a Cabinet post to any race or ethnic group,’ ” JFK announced before the election, Bryant writes. “ ‘That is racism at its worse.’ ” Yet that is exactly what his “strategy of association” called for, except that the black men Kennedy hired were (to borrow from the late David Halberstam) “the best and brightest,” finally being given their shot to shine like Jackie Robinson had in a different “major league” 13 years before. In Kennedy’s first six months in office, the New York Amsterdam News reminded readers after the assassination, the Kennedy White House appointed some 50 black men (and women) to executive branch jobs.

But Louis Martin had already pushed those talking points out over a year before to Democratic party field workers (conveniently, those same talking points found their way to the Chicago Defender on April 21, 1962). In them, Martin emphasized the ceilings JFK had helped black professionals shatter in the federal government. He also reminded them that, unlike previous presidents, the positions Kennedy offered weren’t merely “advisory,” but were, as the headline ran, for “Negro Decision-Makers.” Their names, though largely forgotten to us now, were illustrious and continued being added to the rolls throughout JFK’s 1,000 days.

A Few of the African Americans in the Kennedy Administration

Andrew T. Hatcher, associate White House press secretary, the first black man to hold the No. 2 communications spot in the White House, behind his longtime political compatriot, Pierre Salinger. In fact, according to a profile in Ebony in October 1963, Hatcher pinch-hit for Salinger “200 days … as the official White House spokesmen at press briefings, on the mikes and on the job,” including during “the Mississippi Meredith case.” “The appointment was enough to jar ‘the old pros’ who had long become accustomed to Negroes serving only as porters, messengers, maids, clerks and valets at the White House,” Simeon Booker of Ebony wrote.

Dr. Robert Weaver, administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, “the highest appointive federal office ever held by an American Negro,” the Chicago Defender noted in its coverage of Weaver receiving the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal on June 5, 1962. (JFK tried to elevate Weaver to a full Cabinet member but was rebuffed by Southern Democrats around the same time he pushed to open up federal housing for blacks. Lyndon Baines Johnson, the legislator’s legislator, eventually made it happen, naming Weaver his first H.U.D. secretary in 1966.)

George L.P. Weaver, assistant aecretary of labor for Internal Affairs

Carl Rowan, deputy assistant secretary of state for Public Affairs (later LBJ’s director of the U.S. Information Agency, after Edward R. Murrow, and a nationally syndicated columnist)

Dr. Grace Hewell, program coordination officer, Department of Health, Education and Welfare

Christopher C. Scott, deputy assistant postmaster general for transportation

Lt. Commander Samuel Gravely, of the U.S.S. Falgout, the first black Navy commander to lead a combat ship, according to Martin

Dr. Mabel Murphy Smythe, member, U.S. Advisory Commission on Educational Exchange, Department of State

John P. Duncan, commissioner of the District of Columbia

Clifford Alexander Jr., national security council (later secretary of the army under President Carter)

A. Leon Higginbotham, a member of the five-man Federal Trade Commission, which, in September 1962, made him the first African American ever to be appointed to a federal regulatory agency—and only at age 35. (Higginbotham was a distinguished Philadelphia attorney who had graduated from Yale Law School and served as the city’s NAACP chapter president and former assistant district attorney; I was proud to recruit him and his wife Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham to teach at Harvard after I arrived in 1991.)

Plus:

The ambassadors: Carl Rowan, to Finland; Clifton Wharton, to Norway; and Mercer Cook, to Niger

U.S. attorneys: Cecil Poole, Northern California; and Merle McCurdy, Northern Ohio

President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity: Alice Dunnigan; John Hope; Azie Taylor (later, U.S. treasurer under President Carter); Hobart Taylor; John Wheeler; and Howard Woods.

Federal judges: James Benton Parsons, Northern District of Illinois, the first black federal district judge to serve inside the continental U.S.; Wade McCree, Eastern District of Michigan; Marjorie Lawson, Juvenile Court of the District of Columbia; and, “Mr. Civil Rights” himself (as Louis Martin referred to him), Thurgood Marshall, the Second Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals. A. Leon Higginbotham would have made No. 5 when JFK nominated him for a district court judgeship in October 1963, but after the assassination, he was held over until LBJ submitted his name again in January 1964.

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Madam Walker, the First Black American Woman to Be a Self-Made Millionaire

As I explained in my memoir, Colored People, “So many black people still get their hair straightened that it’s a wonder we don’t have a national holiday for Madame C.J. Walker, who invented the process for straightening kinky hair, rather than for Dr. King.” I was joking, of course, but mostly about the holiday; the history and politics of African-American hair have been as charged as any “do” in our culture, and somewhere in the story, Madam C.J. Walker usually makes an appearance.

Most people who’ve heard of her will tell you one or two things: She was the first black millionairess, and she invented the world’s first hair-straightening formula and/or the hot comb. Only one is factual, sort of, but the amazing story behind it and how Madam Walker used that accomplishment to help others as a job creator and philanthropist might be jarring — and surprisingly empowering — even to the skeptics. I know it was for me in revisiting her life for this column.

Thanks to the work of numerous historians, among them Madam Walker’s prolific great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, as well as Nancy Koehn and my colleagues at Harvard Business School, I no longer see one straight line from “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower” to current menus of extensions, braids and weaves; nor do I see a single line connecting this brilliant, determined person — who struggled doggedly for a life out of poverty, and for black beauty, pride and her own legitimacy (in the face of black male resistance) as a black business woman during the worst of the Jim Crow era — to the most successful black women on the stage today.

“Up From” Sarah Breedlove

On December 23, 1867, Sarah Breedlove was born to two former slaves on a plantation in Delta, La., just a few months after the second Juneteenth was celebrated one state over in Texas. While the rest of her siblings had been born on the other side of emancipation, Sarah was free. But by 7, she was an orphan toiling in those same cotton fields. To escape her abusive brother-in-law’s household, Sarah married at 14, and together she and Moses McWilliams had one daughter, Lelia (later “A’Lelia Walker”), before Moses mysteriously died.

Now that Reconstruction, too, was dead in the South, Sarah moved north to St. Louis, where a few of her brothers had taken up as barbers, themselves having left the Delta as “exodusters” some years before. Living on $1.50 a day as a laundress and cook, Sarah struggled to send Lelia to school — and did — while joining the A.M.E. church, where she networked with other city dwellers, including those in the fledgling National Association of Colored Women.

In 1894, Sarah tried marrying again, but her second husband, John Davis, was less than reliable, and he was unfaithful. At 35, her life remained anything but certain. “I was at my tubs one morning with a heavy wash before me,” she later told the New York Times. “As I bent over the washboard and looked at my arms buried in soapsuds, I said to myself: ‘What are you going to do when you grow old and your back gets stiff? Who is going to take care of your little girl?’ ”

Adding to Sarah’s woes was the fact that she was losing her hair. As her great-granddaughter A’Lelia Bundles explains in an essay she posted on America.gov’s Archive: “During the early 1900s, when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing and electricity, bathing was a luxury. As a result, Sarah and many other women were going bald because they washed their hair so infrequently, leaving it vulnerable to environmental hazards such as pollution, bacteria and lice.”

In the lead-up to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Sarah’s personal and professional fortune began to turn when she discovered the “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” of Annie Turnbo(later Malone), an Illinois native with a background in chemistry who’d relocated her hair-straightening business to St. Louis. It more than worked, and within a year Sarah went from using Turnbo’s products to selling them as a local agent. Perhaps not coincidentally, around the same time, she began dating Charles Joseph (“C.J.”) Walker, a savvy salesman for the St. Louis Clarion.

A little context and review: Along the indelible color line that court cases like Plessy v. Ferguson drew, blacks in turn-of-the-century America were excluded from most trade unions and denied bank capital, resulting in trapped lives as sharecroppers or menial, low-wage earners. One of the only ways out, as my colleague Nancy Koehn and others reveal in their2007 study of Walker, was to start a business in a market segmented by Jim Crow. Hair care and cosmetics fit the bill. The start-up costs were low. Unlike today’s big multinationals, white businesses were slow to respond to blacks’ specific needs. And there was a slew of remedies to improve upon from well before slavery. Turnbo saw this opportunity and, in creating her “Poro” brand, seized it as part of a larger movement that witnessed the launch of some 10,000 to 40,000 black-owned businesses between 1883 and 1913. Now it was Sarah’s turn.

The Walker System

While still a Turnbo agent, Sarah stepped out of her boss’ shadow in 1905 by relocating to Denver, where her sister-in-law’s family resided (apparently, she’d heard black women’s hair suffered in the Rocky Mountains’ high but dry air). C.J. soon followed, and in 1906 the two made it official — marriage No. 3 and a new business start — with Sarah officially changing her name to “Madam C.J. Walker.”

Around the same time, she awoke from a dream, in which, in her words: “A big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix up for my hair. Some of the remedy was grown in Africa, but I sent for it, put it on my scalp, and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.” It was to be called “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” Her initial investment: $1.25.

Sarah’s industry had its critics, among them the leading black institution-builder of the day, Booker T. Washington, who worried (to his credit) that hair-straighteners (and, worse, skin-bleaching creams) would lead to the internalization of white concepts of beauty. Perhaps she was mindful of this, for she was deft in communicating that her dream was not emulative of whites, but divinely inspired, and, like Turnbo’s “Poro Method,” African in origin.

However, Walker went a step further. You see, the name Poro “came from a West African term for a devotional society, reflecting Turnbo’s concern for the welfare and the roots of the women she served,” according to a 2007 Harvard Business School case study. Whereas Turnbo took her product’s name from an African word, Madame C.J. claimed that the crucial ingredients for her product were African in origin. (And on top of that, she gave it a name uncomfortably close to Turnbo’s “Wonderful Hair Grower.”)

It wouldn’t be the only permanent sticking point between the two: Some claim it was Turnbo, not Walker, who became the first black woman to reach a million bucks. One thing about her startup was different, however: Walker’s brand, with the “Madam” in front, had the advantage of French cache, while defying many white people’s tendency to refer to black women by their first names, or, worse, as “Auntie.”

Of course, many would-be entrepreneurs start off with a dream. The reason we’re still talking about Walker’s is her prescience, and her success in the span of just a dozen years. In pumping her “Wonderful Hair Grower” door-to-door, at churches and club gatherings, then through a mail-order catalog, Walker proved to be a marketing magician, and she sold her customers more than mere hair products. She offered them a lifestyle, a concept of total hygiene and beauty that in her mind would bolster them with pride for advancement.

To get the word out, Walker also was masterful in leveraging the power of America’s burgeoning independent black newspapers (in some cases, her ads kept them afloat). It was hard to miss Madam Walker whenever reading up on the latest news, and in her placements, she was a pioneer at using black women — actually, herself — as the faces in both her beforeand after shots, when others had typically reserved the latter for white women only (That was the dream, wasn’t it? the photos implied).

At the same time, Walker had the foresight to incorporate in 1910, and even when she couldn’t attract big-name backers, she invested $10,000 of her own money, making herself sole shareholder of the new Walker Manufacturing Company, headquartered at a state-of-the-art factory and school in Indianapolis, itself a major distribution hub.

Perhaps most important, Madam Walker transformed her customers into evangelical agents, who, for a handsome commission, multiplied her ability to reach new markets while providing them with avenues up out of poverty, much like Turnbo had provided her. In short order, Walker’s company had trained some 40,000 “Walker Agents” at an ever-expanding number of hair-culture colleges she founded or set up through already established black institutions. And there was a whole “Walker System” for them to learn, from vegetable shampoos to cold creams, witch hazel, diets and those controversial hot combs.

Contrary to legend, Madam Walker didn’t invent the hot comb. According to A’Lelia Bundles’ biography of Walker in Black Women in America, a Frenchman, Marcel Grateau, popularized it in Europe in the 1870s, and even Sears and Bloomingdale’s advertised the hair-straightening styling tool in their catalogs in the 1880s. But Walker did improve the hot comb with wider teeth, and as a result of its popularity, sales sizzled.

Careful to position herself as a “hair culturalist,” Walker was building a vast social network of consumer-agents united by their dreams of looking — and thus feeling — different, from the heartland of America to the Caribbean and parts of Central America. Whether it stimulated emulation or empowerment was the debate — and in many ways it still is. One thing, though, was for sure: It was big business. No — huge! “Open your own shop; secure prosperity and freedom,” one of Madam Walker’s brochures announced. Those who enrolled in “Lelia College” even received a diploma.

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, Walker had the Mona Lisa of black-beauty brands. Among the most ridiculous knockoffs was the white-owned “Madam Mamie Hightower” company. To keep others at bay, Walker insisted on placing a special seal with her likeness on every package. So successful, so quickly, was Walker in solidifying her presence in the consumer’s mind that when her marriage to C.J. fell apart in 1912, she insisted on keeping his name. After all, she’d already made it more famous.

To keep her agents more loyal, Walker organized them into a national association and offered cash incentives to those who promoted her values. In the same way, she organized the National Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers Association in 1917. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself,” Walker said in 1914. “I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race.” And for her it wasn’t just about pay; Walker wanted to train her fellow black women to be refined. As she explained in her 1915 manual, Hints to Agents, “Open your windows — air it well … Keep your teeth clean in order that [your] breath might be sweet … See that your fingernails are kept clean, as that is a mark of refinement.”

Reading this, I instantly thought of Booker T. Washington, “the wizard of Tuskegee,” who, while troubled by the black beauty industry, shared Walker’s obsession with cleanliness. In fact, Washington made it critical to his school’s curriculum, preaching “the gospel of the toothbrush,” writes Suellen Hoy in her interesting history, Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness. “I never see … an unpainted or unwhitewashed house that I do not want to paint or whitewash it,” Washington himself wrote in his memoir, Up From Slavery.

I have no doubt this topic would’ve made for interesting conversation between Washington and Walker (after all, having come from similar places, weren’t they after similar things with not dissimilar risks?). Yet, try as Walker did to curry Washington’s favor, her initial forays only met his grudging acknowledgment, even though many of the wives Washington knew, including his own — the wives of the very ministers denouncing products like Walker’s — were dreaming of the same straight styles.

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Who Were the Harlem Hellfighters?

Harlem Hellfighters Homecoming Parade

“Up the wide avenue they swung. Their smiles outshone the golden sunlight. In every line proud chests expanded beneath the medals valor had won. The impassioned cheering of the crowds massed along the way drowned the blaring cadence of their former jazz band. The old 15th was on parade and New York turned out to tender its dark-skinned heroes a New York welcome.”

So began the three-page spread the New York Tribune ran Feb. 18, 1919, a day after 3,000 veterans of the 369th Infantry (formerly the 15th New York (Colored) Regiment) paraded up from Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street to 145th and Lenox. One of the few black combat regiments in World War I, they’d earned the prestigious Croix de Guerre from the French army under which they’d served for six months of “brave and bitter fighting.” Their nickname they’d received from their German foes: “Hellfighters,” the Harlem Hellfighters.

In their ranks was one of the Great War’s greatest heroes, Pvt. Henry Johnson of Albany, N.Y., who, though riding in a car for the wounded, was so moved by the outpouring he stood up waving the bouquet of flowers he’d been handed. It would take another 77 years for Johnson to receive an official Purple Heart from his own government, but on this day, not even the steel plate in his foot could weigh him down.

It was, the newspapers noted, the first opportunity the City of New York had to greet a full regiment of returning doughboys, black or white. The Chicago Defender put the crowd at 2 million, the New York Tribune at 5 million, with even the New York Times conservatively estimating it at “hundreds of thousands.”

“Never have white Americans accorded so heartfelt and hearty a reception to a contingent of their black country-men,” the Tribune continued. And “the ebony warriors” felt it, literally, beneath a hail of chocolate candy, cigarettes and coins raining down on them from open windows up and down the avenues. It would have been hard to miss them, at least according to the New York Times, to whom all the men appeared 7 feet tall.

Yet as rousing as those well-wishers were, the Tribune pointed out, “the greeting the regiment received along Fifth Avenue was to the tumult which greeted it in Harlem as the west wind to a tornado.” After all, 70 percent of the 369th called Harlem home, and their families, friends and neighbors had turned out in full force to thank and welcome those who’d made it back. Eight hundred hadn’t, an absence recalled in the number of handkerchiefs drying wet eyes.

That morning, it had taken four trains and two ferries to transport the black veterans and their white officers from Camp Upton on Long Island to Manhattan, and the parade, kicking off at 11:00 a.m.—an echo of the armistice that had halted the fighting three months before—stretched seven miles long. In his 1845 slave narrative, Frederick Douglass had likened his master to a snake; now a rattlesnake adorned the black veterans’ uniforms—their insignia. On hand to greet them was a host of dignitaries, including the African-American leader Emmett Scott, special adjutant to the secretary of war; William Randolph Hearst; and New York’s popular Irish Catholic governor, Al Smith, who reviewed his Hellfighters from a pair of stands on 60th and 133rd Streets.

In Harlem, the Chicago Defender observed, Feb. 17, 1919, was an unofficial holiday, with black school children granted dismissal by the board of education. A similar greeting—on the same day, in fact—met the returning black veterans of the 370th Infantry (the old Eighth Illinois) in Chicago, Chad L. Williams writes in his 2010 book, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. And in the coming months, there would be other celebrations, even in the Jim Crow South, most notably Savannah, Ga., the state that in 1917 and 1918 led the nation in lynchings, according to statistics published by the Tuskegee Institute. It was, to be sure, a singular season, a pause between the end of hostilities abroad and the resumption of hostilities at home in a nation still divided so starkly, so violently, by the color line.

Congress would not make Armistice Day an official U.S. holiday until 1938, and it would not be called Veterans Day until 1954. But the people of New York didn’t need Congress to tell them what to do when their black fighting men returned home, and so you might say, the first “veterans day parade” in New York associated with “Armistice Day” was held for black soldiers on Feb. 17, 1919, during the month that would eventually be set aside for black history.

Blacks Debate the War Effort

Two years before, on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war in order to enter a conflict between European powers that had started over the assassination of an archduke in 1914. “The World must be made safe for democracy,” the president said. The nation’s allies: the British, French and Russians. Its enemies: Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, the so-called Central Powers.

For some African Americans, Wilson’s rhetoric smacked of hypocrisy. After all, he was the president who had screened Birth of a Nation (a film glorifying the Ku Klux Klan) at the White House and refused to support a federal anti-lynching bill, even though each year averaged more than one lynching a week, predominantly in former Confederate states that had effectively stripped black men of their voting rights. “Will some one tell us just how long Mr. Wilson has been a convert to TRUE DEMOCRACY?” the Baltimore Afro-American editorialized on April 28, 1917 (quoted in Williams). “Patriotism has no appeal for us; justice has,” the Messenger, a Socialist publication launched by editors Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph (of March on Washington fame), declared on Nov. 1, 1917—a sentiment that would land both men in jail under the Espionage Act in 1918 (quoted in Adriane Lentz-Smith’s 2009 book, Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I).

Many more blacks viewed the war as an opportunity for victory at home and abroad. W.E.B. Du Bois, a founder of the NAACP in 1909, urged his fellow African Americans to “Close Ranks” in a (now infamous) piece he wrote for the Crisis in July 1918, despite the persistent segregation of black officers at training camp. “Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy,” Du Bois advised—a stance, Williams notes, that would stir controversy when Du Bois was exposed for making simultaneous “efforts to secure a captaincy” for himself.

In all, Williams writes, “2.3 million blacks registered [for the draft]” during World War I. Although the Marines would not accept them, and the Navy enlisted few and only in menial positions, large numbers served in the army. Some 375,000 blacks served overall, including “639 men [who] received commissions, a historical first,” Williams adds in his essay “African Americans and World War I.”

Wartime Violence

The U.S. Army segregated its black troops into two combat divisions, the 92nd and the 93rd, because, as Williams explains, “War planners deemed racial segregation, just as in civilian life, the most logical and efficient way of managing the presence of African Americans in the army.”

But a different kind of violence soon spread—at home, most notably in East St. Louis, where, on July 2, 1917, the rumor that a black man had killed a white man resulted in the murder of nine whites and hundreds of blacks, not to mention half a million dollars in property damage. Things weren’t much better in the South. On August 23, 1917, black soldiers in the 24th Infantry garrisoned in Houston revolted when one of their comrades was beaten and arrested by two white police officers after he tried to stop them from arresting a black woman. Quickly, rumors flew that a white mob was approaching the camp, which, whether true or not, prompted the black troops to scour the camp for ammunition under the notion that the best defense is a good offense.

Marching through the rain to Houston, they killed 15 people, including four policemen and a member of the Illinois National Guard. Two of the black soldiers died in the fighting, one shooting himself in the head rather than risking capture. “Ten men probably ‘could not begin to tell the complete story of what took place that night,’ ” Lentz-Smith quotes “Army prosecutor Colonel Hull,” yet in the fallout, “[t]hey charged 63 members of the battalion with mutiny,” and hanged 13 in “their army khakis.”

‘Over There!’

Of the 375,000 blacks who served in World War I, 200,000 shipped out overseas, but even in the theater of war, few saw combat. Most suffered through backbreaking labor in noncombat service units as part of the Services of Supply. Lentz-Smith puts the number of combat troops at 42,000, only 11 percent of all blacks in the army.

For the first of the two black combat divisions, the 92nd, the Great War was a nightmare. Not only were they segregated, their leaders scapegoated them for the American Expeditionary Forces’ failure at Meuse-Argonne in 1918, even though troops from both races struggled during the campaign. In the aftermath, five black officers were court-martialed on trumped-up charges, with white Major J. N. Merrill of the 368th’s First Battalion writing his superior officer, “Without my presence or that of any other white officer right on the firing line I am absolutely positive that not a single colored officer would have advanced with his men. The cowardice showed by the men was abject” (quoted in Williams, Torchbearers). Even though Secretary of War Newton Baker eventually commuted the officers’ sentences, the damage was done: The 92nd was off the line.

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

The Black Governor Who Was Almost a Senator

Why didn’t more than one black person serve in the Senate during the Reconstruction era — a condition that persisted until this year, when Sen. Tim Scott served, first with William “Mo” Cowan, and now with Cory Booker?

We know, from the vantage of history, that Reconstruction in the United States lasted little more than a decade, from the dawn of emancipation at the midpoint of the Civil War until the politically expedient withdrawal of federal troops from the conquered former Confederate States of America in 1877. Yet it is important to remember that no one who lived through those fitful years of promise, experimentation and gathering clouds knew how it would turn out, or when. And with former slaves and free blacks being a fledgling but still strong voting presence in the deepest parts of the South, Mississippi sent its second black U.S. senator-elect to Washington in 1875. It was four years after the first, Hiram Revels (whom we met last week), left office. Already waiting there — but still unsworn after two years — was the first black senator Louisiana had sent forth: the state’s former acting governor, P.B.S. Pinchback.

Throughout Reconstruction, white Northern carpetbaggers vied with Southern scalawags for the elephant’s share of Republican Party spoils, but the most ambitious black men in the country were also determined to cash in. The two who almost joined each other in the Senate on March 5, 1875, were no exception. This is their story and that of the glass ceiling (actually a cast-iron dome) they would have smashed by serving together 138 years before Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and William “Mo” Cowan (D-Mass.) pulled off the feat this year, followed by Cory Booker (D-N.J.).

Blanche K. Bruce (R-Miss., 1875-1881)

The first was Blanche Kelso Bruce, a 34-year-old former slave born in Virginia to a black enslaved mother and a white plantation owner. Educated alongside the master’s son, Bruce left home (which by then was Missouri) when the Civil War began and his former study-mate joined the Confederate Army. At the midpoint of the war, Bruce narrowly escaped Quantrill’s Raiders, who, in the course of terrorizing Lawrence, Kansas in August 1863, “shot and hung over 150 defenseless people, as well as every black military man … stationed” there, writes Bruce biographer Lawrence Otis Graham, in his 2006 book, The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America’s First Black Dynasty. Fleeing for safety in Missouri, Bruce eventually opened the state’s first black school in Hannibal. After a year of study at Oberlin College, he worked as a steamship porter in St. Louis before catching wind of the opportunities Reconstruction was about to bring black men with prospects willing to relocate to black-majority states in the Deep South.

Bruce soon established his base of power in Bolivar County, Miss., Graham writes. At one time he served in three roles simultaneously: as tax assessor, sheriff and county superintendent of education. They were positions that earned him white men’s trust and, in the process, generated handsome fees in support of a lifestyle that included purchasing a white man’s sprawling cotton plantation. Bruce’s early sponsor in the Magnolia state was a former Confederate-brigadier-turned-Republican, James Alcorn, who would go on to become governor and U.S. senator. Despite the fact that Alcorn dangled promises of higher office, in the election of 1874 Bruce backed Alcorn’s rival for governor, Adelbert Ames, a Northern carpetbagger, who had offered Bruce something more specific: a ticket to the U.S. Senate. (No wonder Alcorn, then in the Senate himself, refused to escort Bruce to his swearing-in). White Republicans like Alcorn and Ames knew how to count votes, and in black-majority states like Mississippi, it was vital to cut deals with powerbrokers like Bruce who could deliver them.

P.B.S. Pinchback (R-La.)

The other black man walking up the Capitol steps at the start of the 43rd Congress was Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, a member of New Orleans’ black social elite. Like Bruce, Pinchback was the son of a white plantation owner and black slave mother, though apparently his father had emancipated his mother before she gave birth to him in Georgia in 1837. (Let’s just say Pinchback wasn’t their first.) Pinchback moved to Cincinnati with his brother, Napoleon, in 1847. By the time he was 12, he was supporting his family as a cabin boy after his father had died and the white side of the family left the black side penniless and in fear of being re-enslaved.

As a ship steward on the Mississippi, Pinchback learned the gambling arts from watching the more seasoned players onboard. With the hand he’d been dealt, he could’ve fooled most into thinking he was as white as any king in a deck of cards. Really, it wasn’t until the outbreak of the Civil War that Pinchback embraced being “a race man,” when, after a stint with the all-white First Louisiana Volunteers, he recruited black soldiers for the Corps d’Afrique and joined the Second Louisiana Native Guard (later, the 74th U.S. Colored Infantry). Once there, he eventually rose to captain before resigning over discriminatory promotional practices and unequal pay. After lobbying for black schools in Alabama, Pinchback returned to Louisiana in time for the state’s 1868 constitutional convention (a pre-condition for rejoining the Union). As a delegate, he “worked to create a state-supported public school system and wrote the provision guaranteeing racial equality in public transportation and licensed businesses,” as Carolyn Neumann writes in the Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895.

Pinchback was serving as president pro tem of the Louisiana senate when, in 1871, the state’s first black lieutenant governor, Oliver Dunn, died. This left Pinchback to take his place. So far, timing seemed to be Pinchback’s strong suit, and it was again a year later when his nemesis, Louisiana’s white governor, Henry C. Warmouth, was impeached after a bitter election (more on that in a bit). In the fallout, Pinchback stepped in as acting governor from Dec. 9, 1872, to Jan. 13, 1873. It was just a blink of an eye, but as W.E.B. Du Bois noted in his towering 1935 study, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, Pinchback was the only black governor of any state during Reconstruction and remained the only one until Douglas Wilder’s election in Virginia in 1989.

“To all intents and purposes,” Du Bois wrote, Pinchback “was an educated, well-to-do, congenial white man, with but a few drops of Negro blood.” (If anything, he looked more like the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, a native of Scotland, than his famous black contemporary Frederick Douglass.) To Du Bois, it counted for a lot that Pinchback “did not stoop to deny” he had a black mother, “as so many of his fellow whites did.”

Pinchback’s grandson, Jean Toomer, one of the Harlem Renaissance’s most brilliant writers (you might know him as the author of the 1923 novel Cane), had a different take on his grandfather’s decision not to pass for white. “Did he believe he had some Negro blood? Did he not? I do not know,” Toomer (born Nathan Pinchback Toomer) wrote in his essay, “The Cane Years” (contained in the book The Wayward and the Seeking, edited by Darwin Turner). “What I do know is this — his belief or disbelief would have had no necessary relation to the facts.” Pinchback “claimed he had Negro blood, linked himself with the cause of the Negro and rose to power.”

That is, until he got to the Senate.

Pinchback might have assumed he was making the right (pragmatic) choice to back President Grant’s Republican slate in 1872, but when it came to verifying the returns, Pinchback’s old enemy, Gov. Warmouth (before his impeachment), insisted his preferred candidate, the Democrat John McEnery, had won. Warmouth used the machinery of government to try to make it so, even though when Reconstruction began, according to Du Bois, blacks in Louisiana accounted for 82,907 of the state’s 127,639 registered voters. For months — really, years — Louisiana was caught up in a bloody mess, as we saw most gruesomely in my column on theColfax Courthouse Massacre. There were even two inaugurations. “Practically,” Du Bois wrote, “so-called Reconstruction in Louisiana was a continuation of the Civil War.”

As a result, even though President Grant certified William Pitt Kellogg as the state’s duly elected governor, backing him up with military force, the U.S. Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections in Washington threw up a roadblock in front of the black man the Kellogg legislature chose to represent them. You guessed it: P.B.S. Pinchback. (Incidentally, he had also been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives but opted for the Senate.) If all had gone according to plan, Pinchback would have been sworn in March 4, 1873, two years before Blanche K. Bruce. Instead, as the opposition mounted, Pinchback soon found himself the poster child for an entire era of greed and corruption that Mark Twain famously coined “The Gilded Age.”

This is not to exonerate Pinchback, who, according to Eric Foner, in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, as governor, had profited from a public land deal, speculated on insider information and otherwise fed off the patronage system. The point is that during “the Gilded Age,” senators in Washington suddenly seemed to get religion when it came to accepting this politician as one of their own. (To show just what a wheeler-and-dealer Pinchback was, in a posthumous article on Nov. 21, 1925, the Chicago Defender recalled how he was once asked, “Governor, how much do you think the delegates I told you about yesterday would sell out for?” To which “Pinchback, high-spirited, proud and unbending soul that he was, answered, ‘Senator, I cannot tell you that. I am used to buying votes, not selling them.’ “)

The Long Senate Debate

By the time Sen.-elect Bruce of Mississippi arrived for his swearing-in at the Capitol on March 5, 1875, Sen.-elect Pinchback of Louisiana had been awaiting his for two years, without satisfaction. Amazingly, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 had become law just four days before, and it affected all Americans by guaranteeing their right to “full and equal enjoyment of” public “accommodations,” “conveyances” and “other places of public amusement,” even “inns” and “theaters,” without regard to “race and color” or “previous condition of servitude.” Had Pinchback been sworn in on time, he might have been the one black senator to vote for it. (It did, however, receive seven black votes in the House — unfortunately not enough to prevent the law from being watered down through the sinking of its call for integrated schools.)

On swearing-in day, the New York Times reporter on the scene commented that “Mr. Bruce … a colored man of fine physique, intelligent features and gentlemanly bearing, next to [former President Andrew] Johnson commanded most attention from the galleries.” If anything, the Times reporter added, he “bears a striking resemblance to King Kalakaua,” the last king of Hawaii. (It was the heyday of color elitism in the U.S., and the paper of record had to find some way to signal to its readership that Bruce was less than white but a few steps up from black.)

As it turned out, what should have only been a ceremonial day in the Senate ended with an extra session to debate, among other things, what to do with the “other” black senator-elect in the wings. To indicate just how high the stakes were, the Chicago Tribune reporter on the scene noted that in addition to his supporters on the floor, “Pinchback himself sa[id] the Senate should not reject him now that a sure-enough nigger is seated [meaning Bruce].” His case was anything but under the noses of those in attendance, the Tribune made clear; for when Pinchback made his way into “the chamber at a side door, the whole gallery sent up a round of applause.” But this vote wasn’t about making history or garnering applause. When the extra session was over, Pinchback saw his potential Senate colleagues postpone his confirmation in a close 33-30 vote, curiously, with Blanche K. Bruce voting with the majority, perhaps because it seemed like the only available option to stave off an outright rejection on his first day as a Senate freshman.

Believe it or not, the curious case of P.B.S. Pinchback dragged on for another whole year in the Senate — three in all — until Sen. George Edmunds of Vermont, a fellow Republican, pushed through an amendment that inserted the word “no” in the pro-Pinchback resolution. On March 8, 1876, the full Senate approved it, 32 to 29. That five Republicans went along with the Democrats was a clear signal Reconstruction was losing steam, and as I said earlier, politicians always know how to count votes. With President Grant set to leave office after two terms in office, the Rutherford Hayes-Samuel Tilden election eight months later would be among the closest — and most controversial — in the nation’s history. This was until a deal was struck in the House to inaugurate the Republican Hayes in exchange for pulling federal troops out of the South — and with them hope for the recently emancipated slaves until the civil rights movement a century later.

Gov. Pinchback “represented the colored race; he was a representative colored man,” Sen. Alcorn of Mississippi argued just days after Sen. Bruce had joined him in the Mississippi delegation, according to the New York Times on March 17, 1875. But with the wheel quickly turning against such men, what had been almost a blessing at the start of Reconstruction was now a curse. Just before Pinchback went down in defeat, his friend Sen. Olivia Morton of Indiana, “intimat[ed] that if he had not been a colored man he would have been admitted long ago,” according to the New York Times on March 9, 1876. As Neumann writes, it was, Frederick Douglass lamented, “a mean and malignant prejudice of race.” “While the vote was being taken,” the Atlanta Constitution reported on March 9, 1876, “Mr. Pinchback was on the floor of the Senate and stood near the entrance at one of the cloak rooms. As the roll was called he manifested some nervousness, and, soon after the vote was announced, left the chamber.”

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Cory Booker and the First Black Senators

When the brilliant Newark Mayor Cory Booker, a Stanford honors student, Yale Law School graduate and a former Rhodes Scholar, is sworn in as New Jersey’s next U.S. senator on Oct. 31 (a historical event that should be widely heralded as a triumph of vision and one candidate’s unwavering and consistent moral commitment to public service), it will mark only the second time in history that two African Americans will be serving in the Senate at the same time. This milestone, remarkably, was only reached earlier this year after Gov. Nikki Haley of South Carolina elevated Rep. Tim Scott to Jim DeMint’s old seat and Gov. Deval Patrick of Massachusetts appointed his former chief of staff, William “Mo” Cowan, to fill the vacancy left by current Secretary of State John Kerry until a special election could be held in June.

While Sens. Cowan and Scott only had a few months together in office, Booker and Scott will share the same chamber (at least) through 2014 when both must run again — Scott, for the first time, statewide. In both cases, Scott, a Tea Party favorite and the first black senator from the South since Reconstruction, has been matched up with a Northeastern Democrat, one who has already officiated same-sex weddings in his state. What a gesture it would be for them to sit together at President Obama’s next State of the Union address in January. While their respective parties may continue to be divided over how best to represent the “1 percent” and the “99 percent,” the Senate is now 2 percent black. In a nation that has twice elected a black man to its highest office, it is news at least worth noting — and, yes, for many, celebrating.

When Eric Foner of Columbia University, our leading historian on Reconstruction and an advisor on my current PBS series, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, emailed me about these amazing facts the morning after Booker’s victory, I knew I wanted to find out more about our early black senators. From working on the series, I was aware of the nearly 90-year gap separating the nation’s first two, Hiram R. Revels (1870-1871) and Blanche K. Bruce (1875-1881), and the third, Edward W. Brooke (1967-1979), but I had no idea I would discover through research that Revels’ swearing in would be delayed by the dead hand of the worst decision in Supreme Court history, or that before “Jim Crow” — in fact, just a decade after the Civil War — two other black men would almost achieve what Scott and Cowan and Scott and Booker have this year.

That’s right! It could — and, as we’ll see in next week’s column, should — have happened 138 years ago on March 5, 1875, two years before Reconstruction ended. This was when the Senate moved to swear in the (second) black man whom Mississippi had sent to Washington, Blanche K. Bruce, even as it continued refusing to seat the first from Louisiana, P.S.B. Pinchback, a Civil War veteran and former state governor who’d been haunting the halls of Congress for two long years waiting for an answer.

Before deciding on the fate of these two individual black men, however, the senators in power after the Civil War had to settle an even more fundamental question when it came to seating Revels in 1870: Was it too soon, according to the Constitution, for any black man to be legally entitled to serve?

Please join me this week and next as I journey back to Reconstruction days in search of Cory Booker’s oldest “ancestor” in the Senate and of the true — and fullest — significance of the 2 percent glass ceiling he has helped Sen. Tim Scott break for the second time this year. With Election Day on deck, a week from Tuesday, it’s the perfect time for us to recall how precious a right voting is, and how much those who went before sacrificed for us to exercise it.

Hiram R. Revels

Jefferson Davis looking over his shoulder at Hiram Revels in U.S. Senate (Thomas Nast, 1870; loc.gov)

Article I, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution spells out the qualifications for becoming a senator by telling us who can’t: “No Person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty Years, and been nine Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State for which he shall be chosen.”

In late February 1870, there was no question whether the first black senator-elect in American history — and one of the first Mississippi had sent to Washington since the Civil War — was old enough or resided in the Magnolia State. Hiram Rhodes Revels, 42 (at a time when the life expectancy of an average American man was mid-40s), had been born free to mixed-race parents in North Carolina in 1827, before even Andrew Jackson was president. After receiving seminary training in Indiana and Ohio, Revels had traveled the country as an ordained minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and eventually pastored churches in St. Louis and Baltimore. He had studied at Knox College in Illinois. He had helped organize and minister to black troops during the late rebellion. Following the emancipation, he had opened churches and schools for the freed people of Mississippi and served as an alderman and state senator. He impressed many political observers with his oratorical gifts and moderate temperament.

So, no, there was no question about Sen.-elect Revel’s age or his residency — or about the powerful new voting bloc behind him. As W.E.B. Du Bois detailed in his classic 1935 study,Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, Mississippi already had a majority-black population before the Civil War; and, with its slaves now free and under the protection of federal troops, 60,137 blacks registered for the vote in 1867 compared to 46,636 whites.

Blacks also comprised the majority in 32 of Mississippi’s counties, and in the state’s first Reconstruction legislature, convened in 1870, they netted 40 seats, though, as Du Bois points out, based on their numbers, it should have been more. (Until the 17th Amendment was ratified in 1913, state legislatures, not voters, decided who would represent them in the U.S. Senate.) What Eric Foner has called “America’s Unfinished Revolution” was just beginning, and the former slaves of the Deep South were on the verge of reinventing government — they thought, forever.

‘Dred Scott’ Redux

This was raw political power that the Republican Party was eager to embrace and Southern Democrats feared. (Remember, Abraham Lincoln had only been dead five years.) So by the time Revels reached the senate on Feb. 23, 1870 — and so soon after Appomattox — he was showered by applause from the gallery, but met resistance from the Democrats on the floor. Particularly galling to them was the fact that Revels was about to inhabit a seat like the one that their former colleague, Jefferson Davis, had resigned en route to becoming president of the Confederacy in 1861. When Davis was still in the Senate, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) had still been good law, they knew, and it had gone out of its way to reject blacks’ claims to U.S. citizenship — the critical third test any incoming senator had to pass.

In staring down Revels, the Democrats’ strategy wasn’t to rake over his birth certificate (an absurd tactic left to our own time) but to proceed as though nothing had happened in between 1857 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868. (Both of those measures had clarified blacks’ status as citizens, blunting Dred Scott’s force as precedent — the 14th Amendment as a matter of constitutional law.) As a result, by the Democrats’ calculus, Revels, despite having been born a free man in the South and having voted years before in Ohio, could only claim to have been a U.S. citizen for two — and at most four — years, well short of the Constitutional command of nine. It was a rule-based argument, as rigid as it was reactionary. It twisted the founders’ original concerns over allowing foreign agents into the Senate into a bar on all native-born blacks until 1875 or 1877, thus buying the Democrats more time to regain their historical advantages in the South.

So, instead of Sen.-elect Revels taking the oath of office upon his arrival in Washington, he had to suffer two more days of debate among his potential colleagues over his credentials and the reach of Dred Scott. While the Democrats’ defense was constitutionally based, as Richard Primus brilliantly recounts in his April 2006 Harvard Law Review article, “The Riddle of Hiram Revels” (pdf), there were occasional slips that indicated just what animus — at least for some — lurked behind it. “Outside the chamber,” Primus writes, “Democratic newspapers set a vicious tone: the New York World decried the arrival of a ‘lineal descendant of an ourang-otang in Congress’ and added that Revels had ‘hands resembling claws.’ The discourse inside the chamber was almost equally pointed.”

Primus continues, “Senator [Garrett] Davis [of Kentucky] asked rhetorically whether any of the Republicans present who claimed willingness to accept Revels as a colleague ‘has made sedulous court to any one fair black swan, and offered to take her singing to the altar of Hymen.’ ” Can you imagine a senator using such suggestive sexual language on the Senate floor today? (OK, maybe on Twitter.)

Foolishly drawn into the debate, some of Revels’ own supporters contorted themselves trying to work within the Democrats’ framework. Notably, one Republican senator, George Williams of Oregon, staked his vote on Revels’ mixed-race heritage (as Primus indicates, Revels was “called a quadroon, an octoroon, and a Croatan Indian as well as a negro” throughout his life). It was a material fact to Williams, perhaps because, as President Lincoln’s former attorney general Edward Bates had signaled in an opinion during the Civil War, just one drop of European blood was technically enough to exempt a black man from Dred Scott’s citizenship ban against African pure-bloods.

Fortunately for all future black elected officials (just think of the pernicious effects of such a rule, however short-lived, on those who could not claim any obvious white heritage), other Republicans in the caucus refused to play along. As Primus recalls, “Senator Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania [asked his colleagues,] ‘What do I care which pre-ponderates? He [Revels] is a man [and] his race, when the country was in its peril, came to the rescue … I admit that it somewhat shocks my old prejudices, as it probably does the prejudices of many more here, that one of the despised race should come here to be my equal; but I look upon it as the act of God.’ ”

The more decisive act for Republicans, as Cameron’s backhanded comments indicated, was the Civil War, which (hello!) in four years had claimed the lives of 750,000 Americans, rewriting the Constitution in blood. To Republicans, before the country had spoken through the Civil Rights Act or Reconstruction Amendments, Dred Scott had, effectively, been overturned by what Sen. James Nye of Nevada called “the mightiest uprising which the world has ever witnessed.”

Charles Sumner, the radical Republican senator from Massachusetts, understood the costs of that uprising, having shed his own blood beneath the cane of Preston Brooks in one of the most violent episodes in the lead-up to the war — right at his own Senate desk. And Sumner wasn’t about to concede any ground to Dred Scott, which, to him, had been “[b]orn a putrid corpse” as soon as it had left the late Chief Justice Taney’s pen. “The time has passed for argument,” Sumner thundered, as quoted in my book, Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History, 1513-2008 . “Nothing more need be said … ‘All men are created equal’ says the great Declaration; and now a great act attests this verity. Today we make the Declaration a reality. For a long time in word only, it now becomes a deed. For a long time a promise only, it now becomes a consummated achievement.”

The Vote

Whatever the merits — or genuineness — of their various arguments (Primus gives most the benefit of doubt, arguing they were “sufficiently principled to qualify as an exercise in interpreting the Constitution” with a view to larger historical stakes), the Senate nevertheless ended up voting on Revels along strict party lines: 48 Republicans for swearing him in, eight Democrats opposed. At 4:40 p.m. on Feb. 25, 1870, some 56 years before the first Black History Week was celebrated, black history was made in America when Sen. Revels pledged before Vice President Schuyler Colfax to uphold the Constitution.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

’12 Years a Slave’: Trek From Slave to Screen

‘Utter Darkness’

The cast of “12 Years a Slave” and director Steve McQueen (at far right) at the New York Film Festival in October 2013. Photo by Risa Korris.

As a literary scholar and cultural historian who has spent a lifetime searching out African Americans’ lost, forgotten and otherwise unheralded tales, I was honored to serve as a historical consultant on Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, most certainly one of the most vivid and authentic portrayals of slavery ever captured in a feature film. In its blend of tactile, sensory realism with superb modernistic cinematic techniques, this film is 180 degrees away from Quentin Tarantino’s postmodern spaghetti Western-slave narrative, Django Unchained, occupying the opposite pole on what we might think of as “the scale of representation.”

No story tells itself on its own; even “true” stories have to be recreated within the confines and various formal possibilities for expression offered by a given medium, and that includes both feature films and documentaries, as well. Both of these films offer compelling interpretations of the horrific experience of human bondage, even if their modes of storytelling are diametrically opposed, offering viewers — and especially teachers and students — a rare opportunity to consider how the ways that an artist chooses to tell a story — the forms, points of view and aesthetic stances she or he selects — affects our understanding of its subject matter.

One hundred and sixty years before Steve McQueen made any artistic choices, Solomon Northup, the narrator and protagonist of 12 Years a Slave, was eager just to get his story out to the public — and have them believe that what had happened to him was authentic. Think of what it must have been like for Solomon during those first disorienting hours in the pitch black, when, in “the dungeon” of Williams’ Slave Pen off Seventh Avenue in Washington, D.C., he had to reckon with the betrayal that had lured him out of a lifetime of freedom into a nightmare of bondage. “I found myself alone, in utter darkness, and in chains,” Northup wrote, and “nothing broke the oppressive silence, save the clinking of my chains, whenever I chanced to move. I spoke aloud, but the sound of my own voice startled me.”

Not only was Northup suddenly a stranger to himself, in an even stranger place, but with his money and the papers proving his status as a free black man stolen and a beating awaiting every insistence on the truth, Northup was forced into a horrifying new role, that of the paradoxical “free slave,” under the false name “Platt Hamilton,” a supposed “runaway” from Georgia. That all this happened in the shadows of the U.S. Capitol — that in cuffs Northup was shuffled down the same Pennsylvania Avenue where just over a century later Dr. King would be heard delivering his “Dream” speech, a few decades before President Barack Obama and his wife Michelle would parade in hopes of fulfilling it — must have made Northup’s imposed odyssey taste all the more bitter. “My sufferings,” he recalled of the first whipping he received, “I can compare to nothing else than the burning agonies of hell!”

But unlike Dante’s Inferno, the outpost to which Solomon Northup was forced to descend was no metaphorical space replete with various circles housing the damned, but the swamps, forests and cotton fields in the Deep South. “I never knew a slave to escape with his life from Bayou Boeuf,” Northup wrote. After that, the driving force of his life — and story — could be summed up in one question: Would he be the exception?

Here are the facts.

Who Was Solomon Northup?

Spoiler alert: This section of the column — and only this section — contains some information also covered in the film.

Solomon Northup spent his first 33 years as a free man in upstate New York. He was born in the Adirondack town of Schroon (later Minerva) July 10, 1807 (his memoir says 1808, but the evidence suggests otherwise). As a child, he learned to read and write while assisting his father Mintus, a former slave who eventually bought enough farm land in Fort Edward to qualify for the vote (a right that in many states, during the early days of the Republic, was reserved for landowners). Solomon’s mother, Susannah, was a “quadroon,” who may have been born free herself. Solomon’s “ruling passion,” he said, was “playing on the violin.”

Married at 21, Northup and his wife Anne Hampton (the daughter of a free black man who was also part white and Native American) had three children: Elizabeth, Margaret and Alonzo. In 1834, they settled in Saratoga Springs, where Solomon toiled at various seasonal jobs, including rafting, woodcutting, railroad construction, canal maintenance and repairs, farming and, in resort season, staffing area hotels (for a time, he and his wife both lived and worked at the United States Hotel). His “ruling passion,” the violin, also became a way of earning money, and his reputation grew.

In March 1841, Northup was lured from his home by two white men, using the aliases Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, who claimed to be members of a Washington, D.C.-based circus in need of musicians for their sightseeing tour. While in New York City, Brown and Hamilton convinced Northup to journey further South with them, and arriving in Washington, D.C., on April 6, 1841, the trio lodged at Gadsby’s Hotel. The next day, the two men got Northup so drunk (he implied they drugged him) that, in the middle of the night, he was roused from his room by several men urging him to follow them to a doctor. Instead, when Northup came to, he found himself “in chains,” he said, at Williams’ Slave Pen with his money and free papers nowhere to be found. Attempting to plead his case to the notorious slave trader James H. Birch (also spelled “Burch”), Northup was beaten and told he was really a runaway slave from Georgia. The price Birch paid Brown and Hamilton for their catch: $250.

Shipped by Birch on the Orleans under the name “Plat Hamilton” (also spelled “Platt”), Northup arrived in New Orleans on May 24, 1841, and after a bout of smallpox, was sold by Birch’s associate, Theophilus Freeman, for $900. Northup was to spend his 12 years in slavery (actually it was 11 years, 8 months and 26 days) in Louisiana’s Bayou Boeuf region. He had three principal owners: the paternal planter William Prince Ford (1841-1842), the belligerent carpenter John Tibaut (also spelled “Tibeats”) (1842-1843) and the former overseer-turned-small cotton planter Edwin Epps (1843-1853).

Ford gave Northup the widest latitude, working at his mills. Twice Northup and Tibaut came to blows over work, the second time Northup coming so close to choking Tibaut to death (Tibaut had come at him with an ax) that Northup fled into the Great Cocodrie Swamp. Though prone to drink, Edwin Epps was brutally efficient with the lash whenever Northup was late getting to the fields, inexact in his work (Northup had many skills; picking cotton wasn’t one of them), unwilling to whip the other slaves as Epps’ driver or too high on his own talents as a fiddler after Epps purchased him a violin to placate his wife, Mary Epps.

In 1852, Epps hired a Canadian carpenter named Samuel Bass to work on his house. An opponent of slavery, Bass agreed to help Northup by mailing three letters on his behalf to various contacts in New York. Upon receiving theirs, the Saratoga shopkeepers William Perry and Cephas Parker notified Solomon’s wife and attorney Henry Bliss Northup, a relative of Solomon’s father’s former master. With bipartisan support, including a petition and six affidavits, Henry Northup successfully petitioned New York Gov. Washington Hunt to appoint him an agent of rescue. On Jan. 3, 1853, Henry Northup arrived at Epps’ plantation with the sheriff of Avoyelles Parish, La. There was no need for questioning. A local attorney, John Pamplin Waddill, had connected Henry Northup to Bass, and Bass had led him to the slave “Platt.” The proof was in their embrace.

Traveling home, Henry and Solomon Northup stopped in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 17, 1853, to have the slave trader James Birch arrested on kidnapping charges, but because Solomon had no right to testify against a white man, Birch went free. Solomon Northup was reunited with his family in Glens Falls, New York on Jan. 21, 1853.

Over the next three months, he and his white editor, David Wilson, an attorney from Whitehall, N.Y., wrote Northup’s memoir, 12 Years a Slave. It was published July 15, 1853, and sold 17,000 copies in the first four months (almost 30,000 by January 1855). “While abolitionist journals had previously warned of slavery’s dangers to free African-American citizens and published brief accounts of kidnappings, Northup’s narrative was the first to document such a case in book-length detail,” Brad S. Born writes in The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature. With its emphasis on authenticity, 12 Years a Slave gave contemporary readers an up-close account of slavery in the South, including the violent tactics owners and overseers used to force slaves to work, and the sexual advances and jealous cruelties slave women faced from their masters and masters’ wives.

Since then, it has been “authentic[ated]” by “[a] number of scholars [who] have investigated judicial proceedings, manuscript census returns, diaries and letters of whites, local records, newspapers and city directories,” wrote the ultimate authority on the authenticity of the slave narratives, the late Yale historian John W. Blassingame, in his definitive 1975 essay, “Using the Testimony of Ex-Slaves: Approaches and Problems,” in The Journal of Southern History.

In 1854, Northup’s book led to the arrest of his original kidnappers, Brown and Hamilton. Their real names, respectively, were Alexander Merrill and James Russell, both New Yorkers. Though Solomon was able to testify at their trial in Saratoga County, the case dragged on for three years and was eventually dropped by the prosecution in 1857, the same year the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford, which, in part, denied black people were citizens of the United States (and thus they could not sue in federal court).

A free man returned from slavery, Solomon Northup remained active in the abolitionist movement; lectured throughout the Northeast; staged, and performed in, two plays based on his story (the second, in 1855, was titled “A Free Slave”); and was known to aid fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad. To this day, the date, location and circumstances of his death remain a mystery. Northup’s last public appearance was in August 1857 in Streetsville, Ontario, Canada. The last recollected contact with him was a visit to the Rev. John L. Smith, a Methodist minister and fellow Underground Railroad conductor, in Vermont sometime after the Emancipation Proclamation, likely in 1863.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media