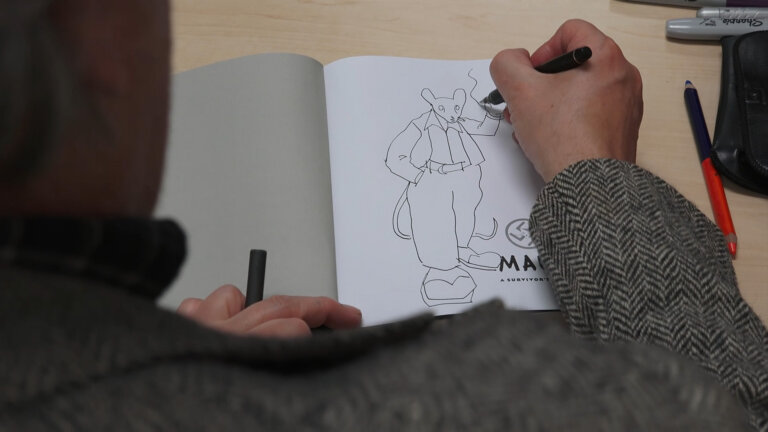

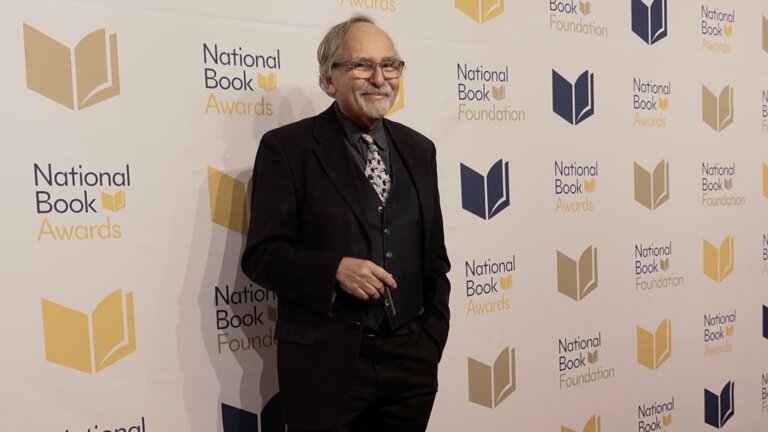

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman, best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus, about his parents’ survival of the Holocaust, has had an immense impact on the world of comics throughout his career. A gifted artist since he was a young child in Queens, New York, Spiegelman started his career at Topps Chewing Gum at just 18 years old. In the early 1970s, he relocated to San Francisco, where he became involved in the underground comix movement and contributed to several comics, including an early version of Maus in Funny Aminals. Upon moving back to New York, he met his wife and collaborator, and art editor for the New Yorker, Françoise Mouly, who he worked with on Breakdowns and several New Yorker covers. When Maus was published in 1991 to great critical acclaim, it became the first, and remains the only, graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. Art continues to create thought-provoking work that reflects his defense of free speech, and proves that comics are “as valid as anything that happened in literature, or in painting or in cinema.”

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman, best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus, about his parents’ survival of the Holocaust, has had an immense impact on the world of comics throughout his career. A gifted artist since he was a young child in Queens, New York, Spiegelman started his career at Topps Chewing Gum at just 18 years old. In the early 1970s, he relocated to San Francisco, where he became involved in the underground comix movement and contributed to several comics, including an early version of Maus in Funny Aminals. Upon moving back to New York, he met his wife and collaborator, and art editor for the New Yorker, Françoise Mouly, who he worked with on Breakdowns and several New Yorker covers. When Maus was published in 1991 to great critical acclaim, it became the first, and remains the only, graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. Art continues to create thought-provoking work that reflects his defense of free speech, and proves that comics are “as valid as anything that happened in literature, or in painting or in cinema.”

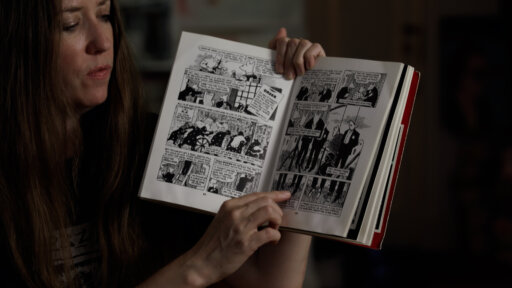

“Art Spiegelman is the guy that reinvented comics as a medium that people took seriously. He showed that comics could express the darkest, most tragic, most complicated, most true things about history, about our relationships, about family,” said artist and writer Molly Crabapple on Spiegelman’s influence.

This timeline explores Art Spiegelman’s life and the major milestones in his career.

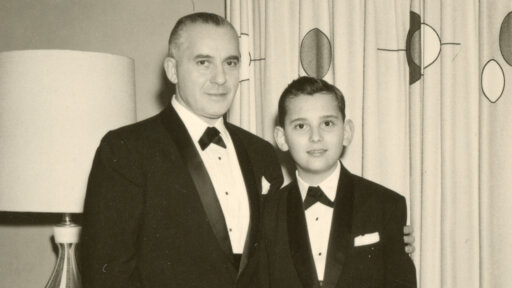

Art Spiegelman is born in Sweden to Vladek and Anja Spiegelman.

The Spiegelman family immigrates to the U.S., settling in Rego Park, Queens in 1955.

Art attends the High School of Art and Design in New York City. During his time there, he creates his fanzine “Blasé” in 1964, and makes money selling his drawings to the Long Island Post.

Art begins working at Topps Chewing Gum under art director Woody Gelman. During his tenure, he illustrates the Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids trading cards.

Art studies at Harpur College of Arts and Sciences at Binghamton University in New York, where he meets and befriends filmmakers and his future collaborators Ken Jacobs and J. Hoberman.

Following a nervous breakdown, Art spends one month at the Binghamton State Mental Hospital. Shortly after his exit, his mother Anja dies by suicide.

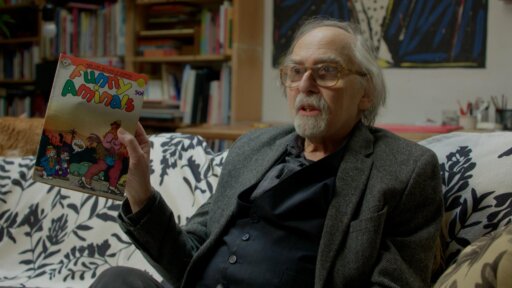

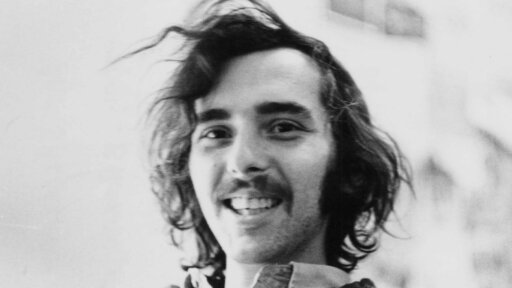

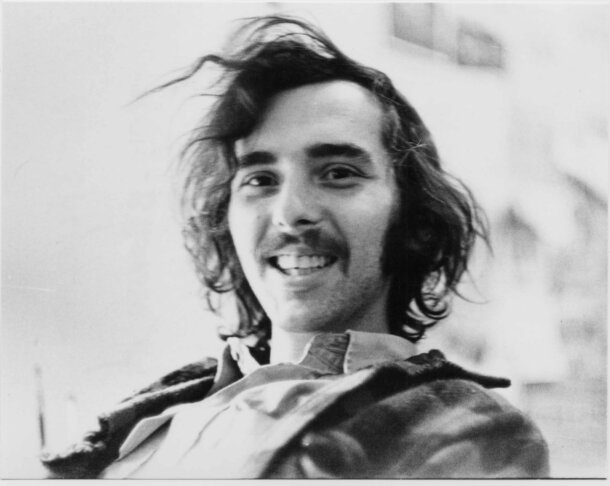

Art moves to San Francisco and becomes involved in the underground comix scene there. He contributes to underground mags “Young Lust,” “Bijou Funnies,” “Real Pulp,” “Bizarre Sex” and more.

Art conducts his first interview with his father Vladek. At this time, “Maus” also makes its first appearance as a comic strip in “Funny Aminals.”

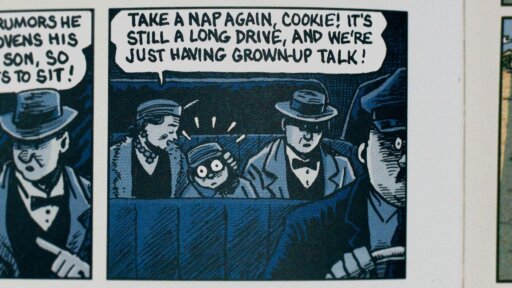

Art edits “Short Order Comics” with Bill Griffith. His comic “Prisoner on Hell Planet” is published in the first issue of “Short Order.”

Art moves back to New York City and meets his future wife and collaborator Françoise Mouly. He contributes drawings to the New York Times Op-Ed page.

Art and Françoise marry. Art publishes “Breakdowns.”

Art starts working on “Maus.” Art and Françoise also start Raw Books & Graphics, a publishing company specializing in comics and graphic novels.

Art and Françoise launch the first issue of “Raw Magazine,” which runs until 1991. The first chapter of “Maus” runs as an insert in the second issue of “Raw,” and a new chapter appears in every issue until the magazine’s end.

Art’s father Vladek dies.

“Maus” becomes the first comic to be reviewed in The New York Times Book Review in an essay titled “Cats, Mice and History: The Avant-Garde of the Comic Strip” by Ken Tucker.

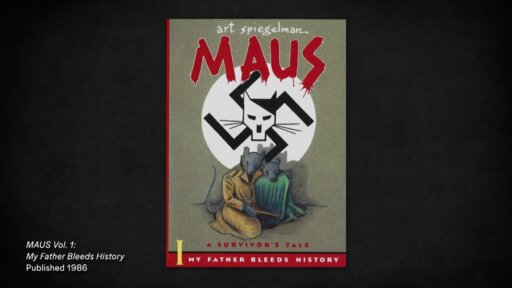

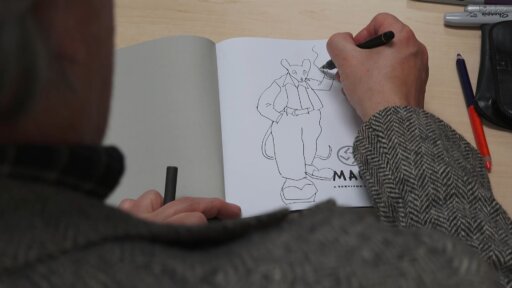

Pantheon Books publishes “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale,” which contains the first six chapters of “Maus.”

Art and Françoise welcome their first child, daughter Nadja on May 13.

In November, Pantheon Books publishes “Maus II,” the second volume containing the last five chapters of “Maus.” Françoise later gives birth to their son Dash on December 29.

“Maus” is awarded a Special Pulitzer Prize, making it the first and only graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. “Maus” also wins the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Fiction.

Art illustrates a then-controversial cover for the Valentine’s Day issue of the New Yorker, depicting a Hasidic Jewish man kissing a Black woman, as a comment on the violence occurring in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

Art receives an Honorary Doctorate degree from Binghamton University. The New York Public Library Centennial Exhibition also includes “Maus” in their list, 100 Best Books of the Century.

For the 10th anniversary of “Maus,” Pantheon Books releases “Complete Maus” as one book, which is honored with a Cultural Achievement Award from the National Foundation for Jewish Culture.

Art serves as the Comix Editor for Details Magazine.

Art is inducted in the Will Eisner Hall of Fame.

Just days after 9/11, Art and Françoise, who was now serving as the art editor for the New Yorker, worked together on the cover for the September 24 issue of the magazine. The cover depicted a black silhouette of the Twin Towers over an all black background.

Art publishes “In the Shadow of No Towers” about his family’s experience on 9/11.

Art is included in Time Magazine’s Time 100 list, as one of the top 100 most influential people in the world.

Art is included in an episode of “The Simpsons,” in an episode titled “Husbands and Knives.”

A new edition of “Breakdowns” is published, including a new essay by Art titled “Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!.”

Art receives an Honorary Doctorate at the Rhode Island School of Design.

“MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus” is published, that includes an interview of Art conducted by scholar Hillary Chute. The book receives the National Jewish Book Award for Best Biography, Autobiography, and Memoir.

In response to the election of Donald Trump, Nadja and Françoise create a comic called “RESIST!,” to which Art contributes.

“Maus” receives a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Book Awards, as McMinn County in Tennessee ban the book from their schools.

McSweeney’s releases its 25th Anniversary Issue, which contains a collectable lunchbox illustrated by Art.

Art publishes a comic about Gaza with Joe Sacco in the New York Review of Books, titled “Never Again and Again.”