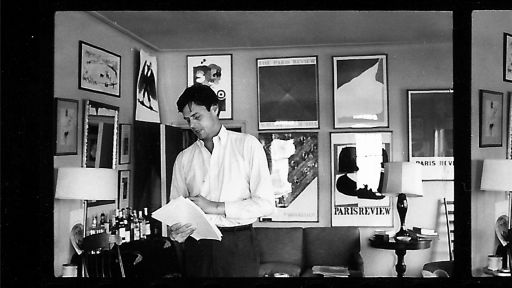

Nine years ago, Terry McDonell wrote an essay for The Paris Review about his friendship with the literary magazine’s co-founder, George Plimpton.

He recalled a story that Plimpton once told him about Ernest Hemingway. While visiting the adventurous novelist at his home in Havana, Cuba—where Hemingway wrote “The Old Man and the Sea” and much of “For Whom the Bell Tolls”—Plimpton agreed to be fitted in a safari jacket. During the fitting, the tailor adjusted the sleeves while Hemingway, who had an identical jacket made from antelope leather, fretted over the silhouette and tried to smooth the coat over Plimpton’s shoulders. “It went on too long and made me uncomfortable,” Plimpton told McDonell years later.

This was the nut of Plimpton’s relationship with style: he was not particular about clothes and didn’t like fussing over them. Yet, he radiated a kind of dashing deshabille that menswear writers have tried to dissect for generations.

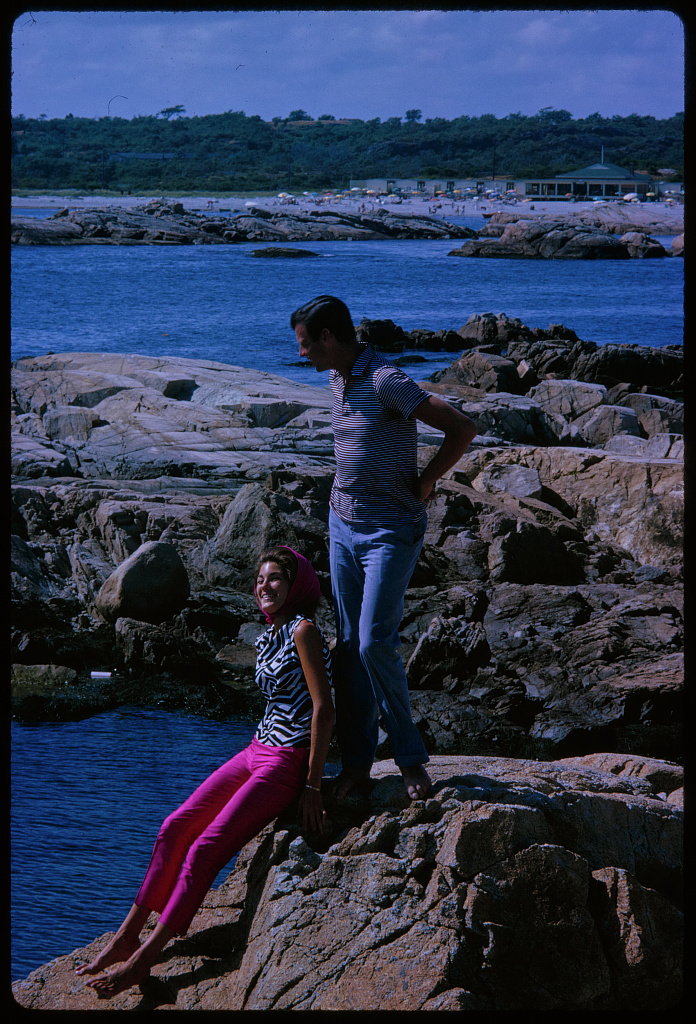

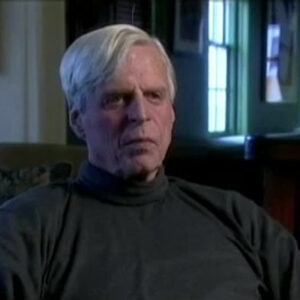

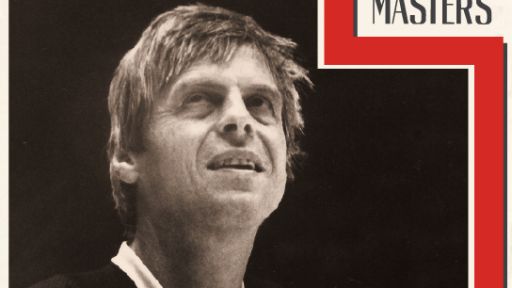

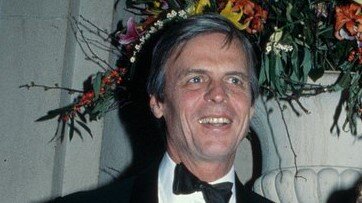

Although he was not particularly interested in clothes, Plimpton was the very glass of fashion and mold of form, at least when it comes to that elusive quality that has long defined classic American male dress. In 1985, photographer Susan Wood captured the writer at his summer home, where Plimpton can be seen wearing a lavender brushed Shetland knit (likely from J. Press), university striped oxford-cloth button-down shirt and brown five-pocket cords while sitting in his paper-strewn writing sanctum, his small children climbing all over him.

While attending the Alan King Tennis Classic games at Caesars Palace in 1978, the writer wore a navy blazer, white polo shirt, striped bucket hat, and shorts that were so short, they would make even fashionable men today blush. Most of all, Plimpton was known for his soft-shouldered suits and sport coats—made from hopsack, seersucker, tweed, gabardine and cotton—all cut with that natural shoulder line that made American style less stuffy than its British counterparts. Plimpton’s clothes never looked freshly pressed, only like he bought something of quality and then, each morning, accidentally tumbled into them while running out of the door. Women’s Wear Daily once accurately described the literary lion as a “wobbly WASP.”

I know it’s passe to post trad pics, but I still love the stuff. Here’s George Plimpton, an American style icon

1. Tennis game w short shorts, bucket hat, sport coat

2. Pink Shetland with cords, white socks, loafers

3. Tweed with leather buttons, OCBD, rep tie

4. ’68 SDS meeting pic.twitter.com/FKVlfwK8tV— derek guy (@dieworkwear) April 13, 2022

It’s hard to pinpoint what made Plimpton’s style so compelling, as men with similar attributes were not so similarly well-attired. Of course, it’s impossible to separate our judgment of his dress from his social class. Plimpton came from a privileged blue-blooded lineage where both of his parents descended from Mayflower passengers. People in his family helped lead the Union Army, build the Union Pacific portion of the transcontinental railroad, and shape American intellectual, political and economic life. Plimpton himself attended Phillips Exeter Academy, a distinguished prep school where his father was a trustee, but was expelled three months before his graduation for what he described as a “tremendous pileup of small crimes.”

“I just wasn’t a good citizen,” he admitted decades later. After being kicked out for pulling a prank on his headmaster, Plimpton got his diploma from Dayton Beach High School before going to Harvard, where he wrote for the Harvard Lampoon and joined the all-male Porcellian Club. While his social class certainly made him familiar with Good Taste—which Pierre Bourdieu correctly identified as the personal habits and preferences of the ruling class—not all men of his background exhibited such discernment.

george plimpton, tastefulness in abundance

brushed shetland sweaters (likely j press’ shaggy dog), oxford button-down shirts (full collar roll), camp mocs, sack suits, foulard ties, fun combos (campaign pins on dinner suit) pic.twitter.com/40MnP16YEr

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) January 18, 2023

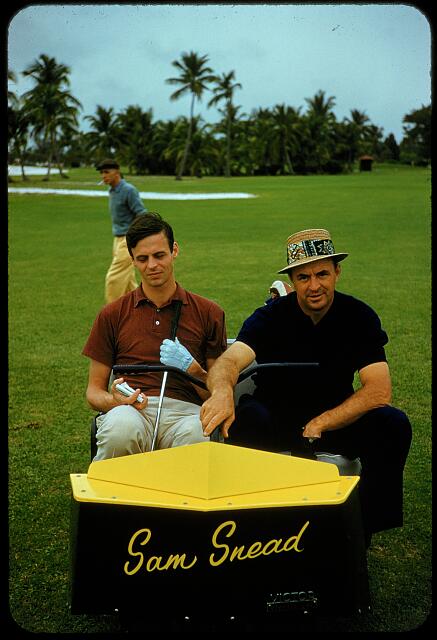

Perhaps Plimpton was stylish because he sat at the intersection of all things cultural. He was a literary critic, a “method” sports journalist, and an actor connected, if only as an escort, to people such as Jane Fonda, the Bouvier sisters and Queen Elizabeth II. The writer traveled and corresponded with Hemingway, pitched to Willie Mays, boxed three rounds with light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore, played quarterback for the Detroit Lions, and worked with Andrew Wyeth, Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol for Paris Review covers. He was also a raconteur, always quick with an amusing story.

Alfred Vanderbilt, Sam Snead & George Plimpton, 1959. Photography by Toni Frissell. Library of Congress.

“Many years ago, I met John Steinbeck at a party in Sag Harbor,” Plimpton once told PEN America, “and told him that I had writer’s block. And he said something which I’ve always remembered, and which works. He said, ‘Pretend that you’re writing not to your editor or to an audience or to a readership, but to someone close, like your sister, or your mother, or someone that you like.’ And at the time I was enamored of Jean Seberg, the actress, and I had to write an article about taking Marianne Moore to a baseball game, and I started it off, ‘Dear Jean…,’ and wrote this piece with some ease, I must say. And to my astonishment, that’s the way it appeared in Harper’s Magazine. ‘Dear Jean…’ Which surprised her, I think, and me, and very likely Marianne Moore.”

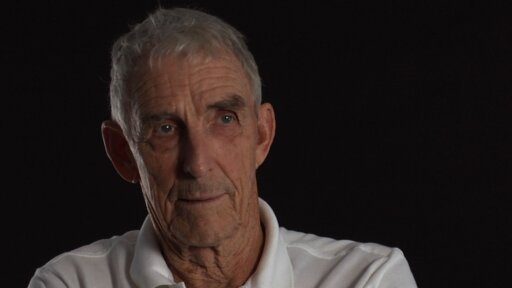

But again, only some culture writers are so well-remembered for their style. Perhaps Plimpton’s can be chalked up to his genial demeanor and gentle appearance, as he possessed watery blue eyes that crinkled at the corners and, by his admission, an avian build of the “stilt-like, wader variety—the avocets, limpkins and herons.” He spoke with a charming accent that his son Taylor once described as a mix of “old New England, old New York, tinged with a hint of King’s College King’s English.” Plimpton was a “patrician everyman,” as David Remnick once described him, who somehow seemed approachable despite having all the trappings of New York privilege: homes in the Upper East Side and Long Island; memberships to Century Association and Traveller Paris; and invites to every high-society soiree.

Whatever made Plimpton’s style so compelling, it has almost completely disappeared from modernity, preserved only as a fantasy through Ralph Lauren’s depictions of patrician life. Plimpton passed away in 2003, about a decade after Casual Friday swept through America and a year before the founding of Facebook. In the following years, Mark Zuckerberg’s hoodie and jeans uniform would become a new status symbol, representing the whiz-kid meritocracy of the New Economy that opposed the traditional coat-and-tie industries back East. As financial capital has shifted, so have the markers for cultural status.

“New money today dwarfs old money,” says David Marx, author of “Status and Culture,” a book about how our pursuit of status shapes our cultural consumption and production. “You could I.P.O. your tech start-up and make more money than any trust fund kid would see in their lifetime. Whereas cultural capital in the 1980s may have come from being able to wear a tweed jacket and talk about art and literature to George Plimpton at a Paris Review party, people such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg aren’t interested in that type of culture today. Cultural capital now comes from wearing sneakers and being able to talk about Danish restaurants with Chris Sacca on a private plane. Old Money’s influence on society today is incredibly weak, so the original set of aesthetics associated with that group has been detached from power and now exists as pure fashion.”

“New money today dwarfs old money,” says David Marx, author of “Status and Culture,” a book about how our pursuit of status shapes our cultural consumption and production. “You could I.P.O. your tech start-up and make more money than any trust fund kid would see in their lifetime. Whereas cultural capital in the 1980s may have come from being able to wear a tweed jacket and talk about art and literature to George Plimpton at a Paris Review party, people such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg aren’t interested in that type of culture today. Cultural capital now comes from wearing sneakers and being able to talk about Danish restaurants with Chris Sacca on a private plane. Old Money’s influence on society today is incredibly weak, so the original set of aesthetics associated with that group has been detached from power and now exists as pure fashion.”

Ironically, as tech billionaires dress down in sneakers, hoodies and T-shirts to seem more relatable to the middle class, income inequality has worsened every decade since the 1980s (arguably the last decade for the coat-and-tie aesthetic). Tech titans today only affect the kind of nonchalance that Plimpton naturally possessed, but their style—and those who follow them—is less remarkable. Plimpton was the last of his kind—a man whose crumpled style was natural and enviable, reflecting a uniquely American character that shaped the 20th century but seems less relevant in the 21st.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.