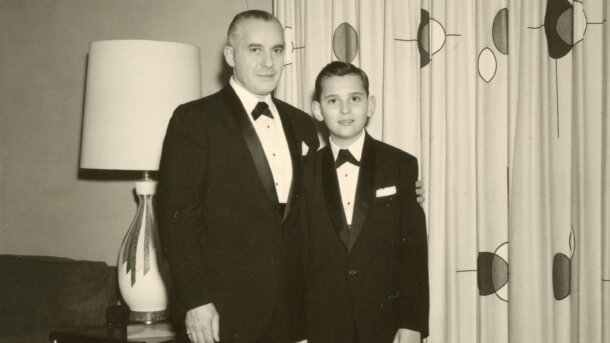

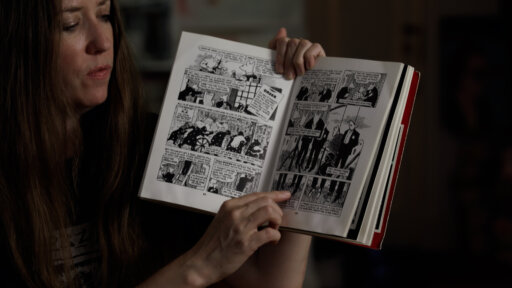

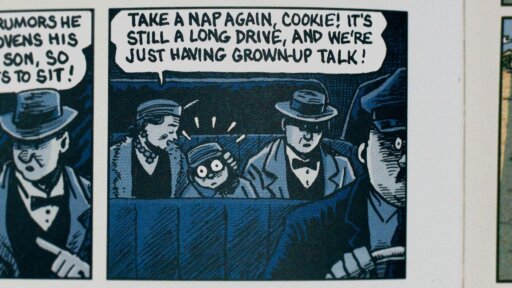

From the first spread of Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir “Maus,” one can already glean his signature mix of the autobiographical, the fictional and the poetic. “It was summer, I remember I was ten or eleven,” “Maus” begins. Three mice roller skate through a neighborhood, rendered in simple, scratchy pen strokes. A dog in a collared shirt and pants, a toothpick sticking out of his teeth, mows the lawn. One of the mice shouts back to the group: “Last one to the schoolyard is a rotten egg!” The narrator—Artie, one of the mice—breaks a roller skate and his friends roll away without him. He finds his father sawing a piece of wood outside of their garage. He explains how his friends skated away without him, and his father stops what he’s doing: “Friends? If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week… THEN you could see what it is, friends…”

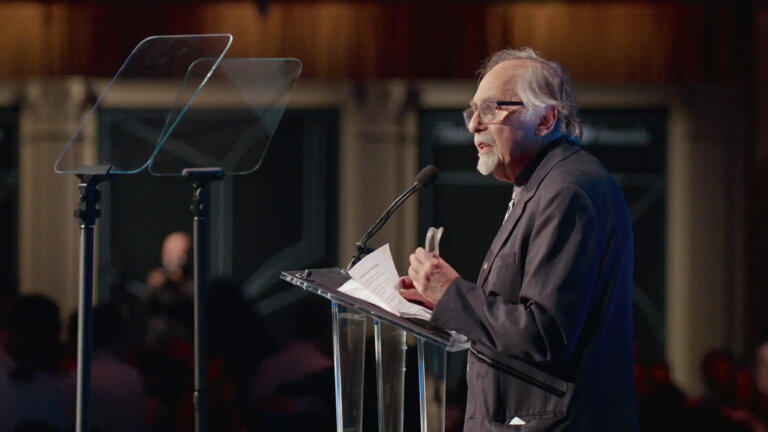

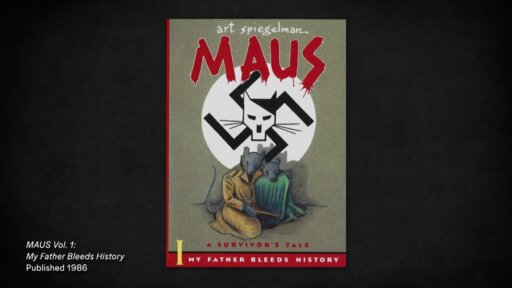

The childhood scene, almost cliché in its mundanity (“a rotten egg”), is pierced by his father’s haunting comment. And so we have the ingredients for Spiegelman’s exploration of memory, history and intergenerational trauma in just two spreads. Across his career—from the experimental underground comix of the 1970s to his boundary-pushing work in RAW magazine and his later reflexive essays and illustrated covers—Spiegelman has consistently interrogated the possibilities and limits of the comics form with those of autobiography and memoir. “Maus” weaves the experience of Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, in Poland during the war, with the experience of trying to retrieve that story. The comic form is integral to this probing of the past. Neither resolutely fiction or nonfiction, film or novel, the comic is a special genre in itself, one that Spiegelman once called “time turned into space, a perfect container for memory.” The same pen that writes the dialogue and narration also constructs the images that we see, as if word and image were flipsides of the same wobbly, inky line.

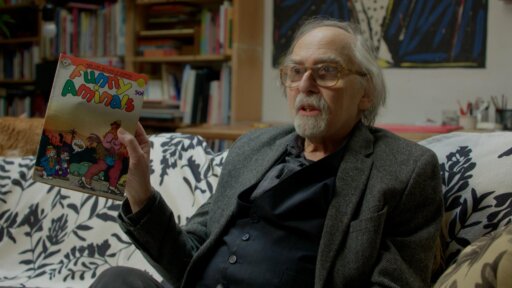

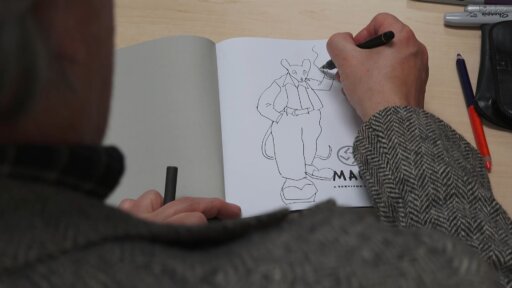

One of Spiegelman’s most notable stylistic choices is his use of animal allegory: Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Americans as dogs, and Poles as pigs. On one hand, this may seem to reduce these figures to species stereotypes. On the other, it gives historical—and personal—memories a sheen of abstraction. We aren’t allowed to rest in the fact that this is not a story; we are constantly made aware that Spiegelman is in the process of shaping this artifice. The characters’ faces are masks, literally and figuratively. In some scenes set in the postwar period, the mask slips: characters wear mouse masks tied with string. The allegory is unstable, provisional. It does not explain or resolve history, but creates a space where history is mediated.

This commitment to mediation and formal play runs throughout Spiegelman’s career. In his earlier underground works—such as “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” which appears within “Maus” itself—Spiegelman experiments with raw, expressionistic drawing and harrowing autobiographical material. RAW, the influential comics anthology he co-edited with Françoise Mouly in the 1980s, became a showcase for avant-garde comics that questioned narrative coherence, aesthetic polish and conventional storytelling. Even in later projects like “In the Shadow of No Towers” (2004), Spiegelman uses collage, fragmentation and juxtaposition to explore trauma—this time, his own response to 9/11—in ways that resist closure or easy interpretation.

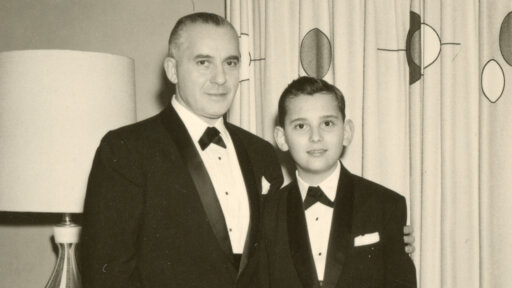

This mediation becomes even more pronounced in “Maus”’s recursive, interwoven structure. The book frequently shifts between past and present, interweaving his father’s wartime narrative with scenes of Art interviewing him in Rego Park, New York. These present-day sequences are deliberately claustrophobic and emotionally fraught, just as in the first scene with the roller skates. Art and Vladek bicker. Telephones, exercise bikes, pill bottles clutter each panel. They misunderstand each other, they fail to connect. Spiegelman draws himself and his father in small, cramped rooms, the architecture and nature often crowding into them.

In Spiegelman’s comics, the past does not pass smoothly into the present. Instead, it arrives broken, tumbling into small rooms and childhood memories. Sometimes, the act of plundering that memory comes with its own consequences: in “Maus II,” Art famously depicts himself in a mouse mask atop a mountain of corpses, agonizing over the commercial and cultural success of “Maus I.” Autobiography in his work is not only about self-knowledge, but about how tortured, futile and doubtful that desire may be. He does not cast himself as heroic or fully understanding, instead, he often draws himself as depressed, confused, resentful and often guilty. Spiegelman’s work can’t help but cannibalize the events of his life. Sometimes it leads to more pain. But other times, that metabolizing helps construct a way forward.

In Spiegelman’s comics, the past does not pass smoothly into the present. Instead, it arrives broken, tumbling into small rooms and childhood memories. Sometimes, the act of plundering that memory comes with its own consequences: in “Maus II,” Art famously depicts himself in a mouse mask atop a mountain of corpses, agonizing over the commercial and cultural success of “Maus I.” Autobiography in his work is not only about self-knowledge, but about how tortured, futile and doubtful that desire may be. He does not cast himself as heroic or fully understanding, instead, he often draws himself as depressed, confused, resentful and often guilty. Spiegelman’s work can’t help but cannibalize the events of his life. Sometimes it leads to more pain. But other times, that metabolizing helps construct a way forward.

Spiegelman’s autobiographical comics map the past’s incursion on our present, and they give us a roadmap for how we may process paths towards the future. “Maus” ends as Artie learns that his father, in a depressed state, burned his mother’s diaries. He walks away, angry. He calls his father a “murderer” for destroying them, and by proxy, the memories inside. In Spiegelman’s own work, he attempts to do the opposite. Not to murder the past but to embrace it and its pain. The work of comics is the work of making life.