Professor Ingrid Anderson reflects on studying under and later teaching the work of Elie Wiesel, and his lessons that trauma can transform into “a valuable tool in the fight for justice.”

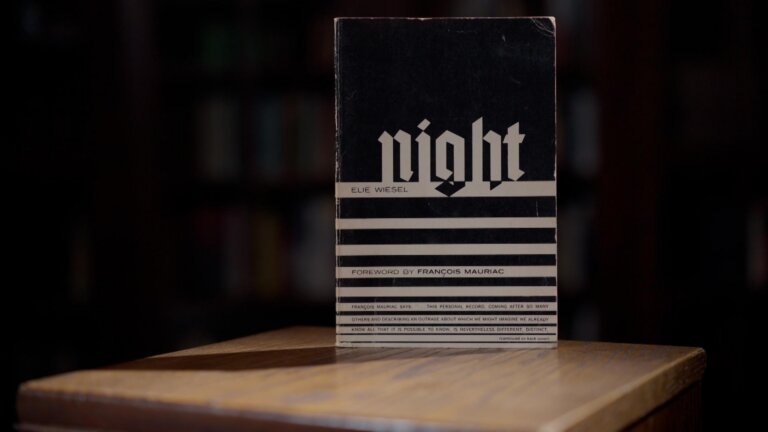

When I teach a course on the work of Elie Wiesel, I don’t teach “Night.” It is not even on the syllabus. “Night” is a beautiful text, even as it demands that its readers bear witness to hell on earth. It is devastating, even when its final pages foretell Wiesel’s phoenix-like unfolding into the man he became—a man known for Nobel Prize-winning prose and the audacity of a vigilante, but whose most treasured task was teaching in the university classroom.

I cannot teach his work to my own students without remembering what it was like to discover it myself. When I registered for one of Wiesel’s classes for the first time, I did so at the insistence of my academic advisor, who stated, “Take whatever he teaches.” Not only had I never read “Night” before, but I had never even heard of it. I simply knew Elie Wiesel was an important figure in neo-Hasidism and was eager to learn about the Baal Shem Tov and his disciples from him. Nothing could have prepared me for how working with Professor Wiesel for the next five years would change my life.

The books we read that first semester were not about genocide or undeserved suffering—or at least not exclusively about those things. They were primarily about Jewish joy, unextinguishable even in the face of loss and despair.

For Wiesel, Hasidic thought explored the intricacies of Jewish history and theology and declared from the rooftops that Judaism does not survive to spite its enemies. Judaism survives because it delights in creation, despite its challenges and mysteries. It chooses life because life is worth living. Therefore, survival is not a destination. It is the beginning of a much longer journey—back to the land of the living, toward the possibility of happiness, and as he would sometimes say about his own experience, toward making survival mean something.

The Hasidic masters featured in “Souls on Fire,” Wiesel’s first book-length project on Hasidut, were unsung heroes—his unsung heroes. They were brilliant human beings, full of love for God and humanity. They were righteous men; they were irreverent misanthropes; they were defiant on behalf of mankind, and sometimes even on behalf of God Himself. They made mistakes and delivered miracles. Some suffered losses beyond words; some hid away from humanity for years on end, only to re-emerge battered and heartbroken, but undefeated. They taught by doing. They taught by loving. They taught by failing spectacularly. They taught by admitting their mistakes and learning from them.

Wiesel’s Hasidic masters were representative of what, for me, became the most salient of his many lessons: If you survive significant trauma, your experience will change you forever, and become a part of who you are. It does not define you. And it can become a valuable tool in the fight for justice and make you strong in the face of great adversity. Reaching this place, this place that goes beyond the trauma, requires both profound acceptance—that you cannot undo what has been done to you—and unbreakable defiance—of the lie that we are helpless to prevent undeserved suffering. It takes effort. It is a journey that we do not take alone.

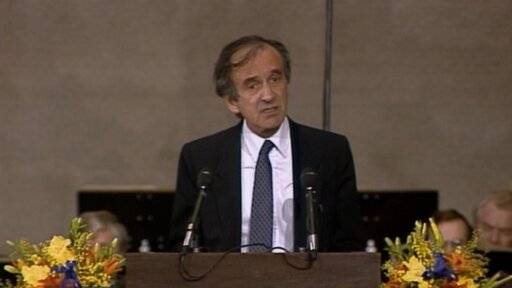

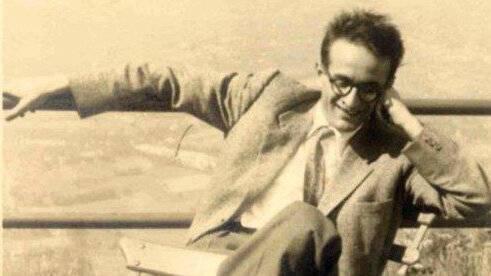

Often, the students who study Wiesel’s work with me have already read “Night.” Therefore, when they try to imagine who he was as an artist and a human being, he is some version of the teenage boy who watched his father die in the snow, who broke the first looking glass he gazed into since before his community was forcibly displaced, with a grief-stricken but defiant fist. He is a teenage boy at the beginning of this sojourn toward a life committed simultaneously to acceptance and defiance. The Wiesel I knew, though, was no longer that boy. Yet his body of work, which includes memoirs, essays, plays, sonnets, biblical and Talmudic commentaries, Hasidic tales, speeches, syllabi, and even the traditional melodies, or niggunim, he sometimes sang to us, remains animated by Wiesel’s timeless invocation of the human condition.

As Wiesel aged, the tenor of his work did, too. When I asked some of my students how we might account for this, they stated with calm certainty that works like “Sages and Dreamers” and “Open Heart” were written when Wiesel was in a different stage of recovery than when he wrote “Night,” “Dawn,” and “Day.” He had married and had a child, gone beyond surviving to bear witness.

All I could do as they offered this astute analysis was smile. I recalled the Tractate Shabbat of the Babylonian Talmud, which recounts the story of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai and his son’s emigration from Jerusalem after the Temple fell to Roman forces around 70CE. After hiding in a cave for 12 years to avoid execution at the hands of the Romans, they emerge at the behest of the prophet Elijah, who tells them that, after the emperor’s death, the decree of execution is now void. After seeing a farmer working his fields, they both exclaim, “They forsake life eternal and engage in life temporal!” The text then states that “whatever they cast their eyes upon was immediately burnt up,” and a “Heavenly Echo” cried, “Have you emerged to destroy My world: Return to your cave!” After another year in the cave, they were commanded to return to the world, and “wherever [one of them] wounded, [the other] healed.”

This story was one of Professor Wiesel’s favorites. In “Sages and Dreamers,” Wiesel writes that Rabbi Shimon had to “go beyond suffering…in order to rediscover compassion and understanding.” The last year in the cave was “a year beyond: beyond suffering, beyond fear, beyond solitude. For suffering confers no privilege on anyone; it all depends on what one does with it. If it leads to resentment and revenge, it is doomed to remain weak and sterile; if it becomes an opening toward man, then it may turn into strength… When Shimon left his prison cave for the first time, he felt what our generation’s survivors felt when they saw what happened—or that nothing happened—while they were away. Only then were they confronted with the real problem: what to do with their anger, their pain, and their despair…any person can save the world or destroy it. The ability, nay, the necessity, to transform curses into blessings, darkness into light.”