In the golden era of Hollywood, directors were often artisans as much as they were artists.

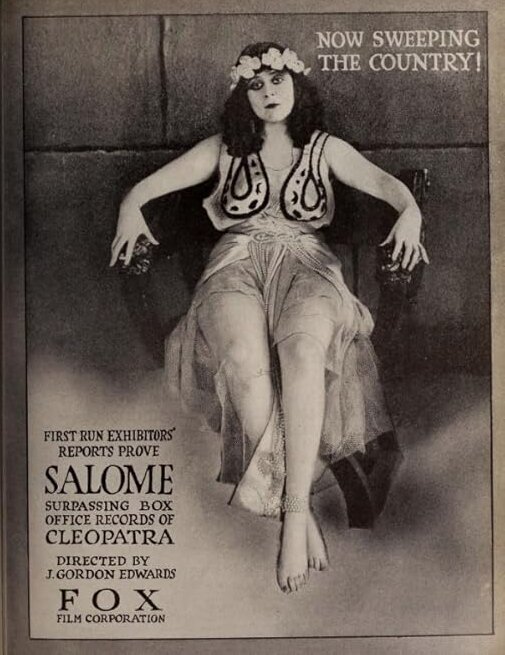

The studios were factories for storytelling, churning out endless variations in a few core styles—the Western, the crime film, the women’s picture, the musical—and bringing in directors to keep the trains running, oversee production and hopefully add a bit of visual pizzazz to the whole. One of these filmmakers was named J. Gordon Edwards, and he made his reputation in the silent era, overseeing most of famed femme fatale Theda Bara’s movies. He was one of countless filmmakers, some of them famous (“I’m ready for my close-up, Mr. DeMille!”) and many relatively anonymous, who helped to build the American film industry in its earliest years.

J. Gordon had a grandson who was enamored of the movies as well, and would eventually join the family business. But by the time Blake Edwards got his start as a director, having first worked as an actor in movies like 1946 Best Picture winner “The Best Years of Our Lives,” the dream factory was beginning to crumble. The rise of television and the antitrust ruling requiring studios to sell off their movie-theater holdings pushed Hollywood to pour its resources into lavish widescreen epics in the hopes of wooing back their audience, and the era of the quietly brilliant jack-of-all-trades director reached a halt.

Except for one man. Blake Edwards thrived as the industry stalled, demonstrating his ability to direct everything from the submarine comedy “Operation Petticoat” (1959) to the stark alcoholism drama “Days of Wine and Roses” (1962).

Edwards is the connector linking the remnants of Hollywood’s golden age to its auteurist future.

Perhaps you did not remember that Edwards directed Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961). Perhaps, too, you did not know that over the course of more than three decades as a filmmaker, he also directed “10” (1979), “Victor/Victoria” (1982), and six “Pink Panther” films. That is OK. Blake Edwards was a sterling example of what American moviemakers could do without requiring much in the way of acclaim or personal notoriety.

Holly Golightly remains the most beloved of Hepburn’s roles, as well as an instant icon of Manhattan’s wounded romanticism, inspiring countless visitors and seekers to gaze longingly into the Tiffany’s window in the hopes of finding themselves there. Holly is still a touchstone of aspirational elegance in adolescent bedrooms and dorm rooms, but “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” is surprisingly funny, as in the sequence where Holly and Paul (George Peppard) convince a stuffy Tiffany’s clerk to engrave a ring procured from a Cracker Jack box.

Edwards prospered in the overlapping Venn diagram of romance and comedy, but one of his most famous characters was also a demonstration of artistic flexibility. Considering all the sequels, prequels, reboots and returns that would follow, you would be forgiven for assuming that you know all about “The Pink Panther.” But the 1963 original does not star Peter Sellers. While Sellers appears in a supporting role as the dim-witted Inspector Clouseau, the movie features David Niven as a suspected jewel thief attempting to boost a precious jewel—called the Pink Panther—from Claudia Cardinale. The result is an attempt at pan-European romantic thrills that came out the same year as “Charade,” and is, at best, a pale imitation of that Cary Grant-Audrey Hepburn classic.

But then something interesting happened. Edwards realized that audiences preferred the bumbling to all the champagne and roses, and came back the next year with “A Shot in the Dark.” It had the familiar mincing Henry Mancini theme and the credit sequence featuring the now-iconic animated Pink Panther, but more than anything it had the ludicrous Clouseau, whom Edwards and Sellers had reimagined as the clown prince of what would become a small fleet of whimsically French detective farces, in which Clouseau would regularly step out of his car into a fountain or spray the ink from a fountain pen directly into his eye, all while unfurling an endless string of vaguely Gallic babble.

Edwards’ entire career resembled the shift from “The Pink Panther” to “A Shot in the Dark.” He was a craftsman and entertainer, the ideal representative of a transitional era in Hollywood from the golden age of the studios to the independent-minded American New Wave of the 1970s. In a series of collaborations with Sellers, Edwards gave the dazzlingly gifted British comedian the space to remake the American comedy after his own image: sneaky, whimsical, physically adept.

So much of contemporary comedy has emerged from under the star of Blake Edwards: the larger-than-life characters; the casual absurdism; the hijacking of familiar genres for the purposes of comedy; the pilfering of the warped costume trunk of stereotype to create something fresh.  Without the influence of Inspector Clouseau, it is nearly impossible to imagine the career of Mike Myers, he of the Scottish accents and wildly incompetent European secret agents. Will Ferrell borrowed liberally from the Sellers/Edwards playbook for many of his bombastic, narcissistic characters in films like “Zoolander” (2001) and “Talladega Nights” (2006). Steve Martin, himself the master of strategically wielded stupidity in films like “The Jerk” (1979), had a late-career renaissance playing Clouseau in a pair of updated “Pink Panther” films.

Without the influence of Inspector Clouseau, it is nearly impossible to imagine the career of Mike Myers, he of the Scottish accents and wildly incompetent European secret agents. Will Ferrell borrowed liberally from the Sellers/Edwards playbook for many of his bombastic, narcissistic characters in films like “Zoolander” (2001) and “Talladega Nights” (2006). Steve Martin, himself the master of strategically wielded stupidity in films like “The Jerk” (1979), had a late-career renaissance playing Clouseau in a pair of updated “Pink Panther” films.

Of all of Edwards’ collaborations with Sellers, though, the best might be the underrated “The Party” (1968), in which Sellers plays an Indian visitor named Hrundi V. Bakshi. The brownface makeup and fish-out-of-water stereotypes make for a high barrier to entry (and may remind some viewers of the racist depiction of Holly’s Japanese neighbor in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”), but the film’s crudity is counterbalanced by a remarkable comedic delicacy. [Editor’s Note: For more context about stereotyping and discrimination in film history, explore this collection.]

“The Party” is a messy masterpiece of American comedy, a homegrown equivalent of Jacques Tati’s dialogue-avoidant, physically ingenious Monsieur Hulot films. It is a comedy of near-total silence, the kind of film Edwards’ grandfather might have made if he had been assigned to work with Fatty Arbuckle or Harry Langdon. Sellers seeks to rescue his shoe from the pool, and accidentally flings it into a passing tray of hors d’oeuvres; in a well-meaning attempt at kindness, he seeks to scrub an elephant clean (just roll with it, OK?) and unleashes an avalanche of bubbles that fills the entire party. Bakshi is a cruder Clouseau, and “The Party” is the greatest of Edwards’ celebrations of comedic chaos. The film channeled the uncertainty of Hollywood in the 1960s, a genteel cocktail soiree suddenly drowned in soap and water.

But “The Party,” like Edwards’ career, was not a cautionary tale; it was comic anarchy delightfully loosed upon the world.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.