Early in Blake Edwards’ dizzying musical farce “Victor/Victoria,” would-be superstar Victoria (Julie Andrews) attempts to explain to faded nightclub mainstay Toddy (Robert Preston) just why their scheme is doomed.

Toddy has proposed that Victoria make a splash in Paris’s nightclub scene by pretending to be a man who performs as a woman, creating a truly head-spinning amount of drag for Victoria to navigate. Toddy insists it will not be difficult. “I am personally acquainted with at least a dozen men who act exactly like women – and vice versa,” he says.

Toddy has proposed that Victoria make a splash in Paris’s nightclub scene by pretending to be a man who performs as a woman, creating a truly head-spinning amount of drag for Victoria to navigate. Toddy insists it will not be difficult. “I am personally acquainted with at least a dozen men who act exactly like women – and vice versa,” he says.

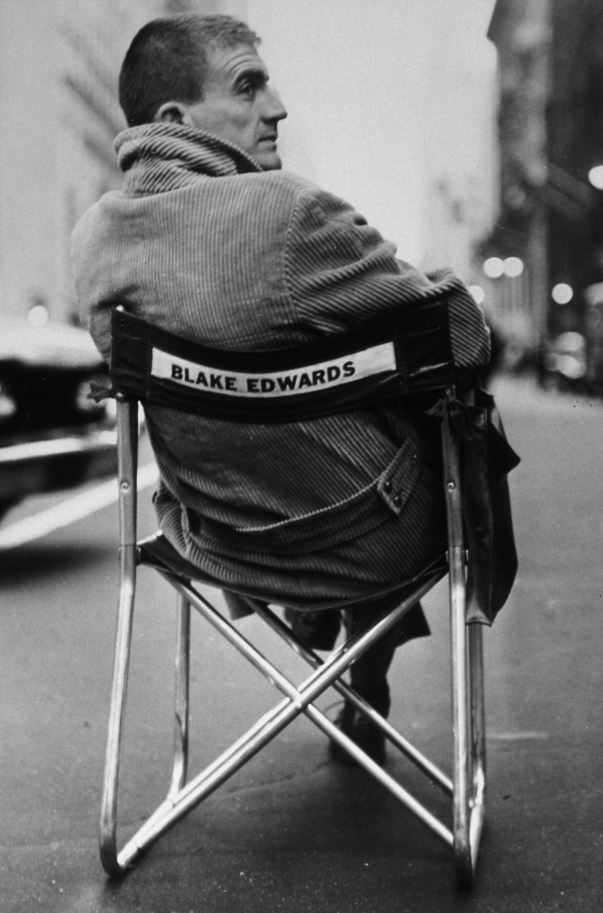

Across his career, Edwards was fascinated by the odd, restrictive, utterly made-up rules society has placed around the idea of gender.

His characters dressed in drag or flouted contemporary sexual mores. Women wound up in spaces traditionally occupied by men and vice versa. And yet also across his career, Edwards would let himself pursue these ideas only so far, as both “Victor/Victoria” and his less-seen 1991 gender comedy “Switch” display. To be sure, Edwards’ playfulness around queerness and gender play stood out in a time when both were treated as objects for cruel mockery, whether via lampooning overly dramatic and feminine gay men, deep-voiced and barrel-chested trans women, or ostentatiously butch lesbians. Edwards leaves room for the humanity of his characters in a way other directors at the time did not. At the same time, his work reflects the limitations in viewpoint common at the time.

“Victor/Victoria,” released in 1982, served as one of Edwards’s critical and commercial high watermarks. The film was not the first time he would work with Andrews, to whom he was married from 1969 until his death in 2010, but it was the film where his talents for giddy farce and her talents as a musical performer meshed most wonderfully. The 1980s were a dismal time for onscreen musicals, meaning “Victor/Victoria,” which is stacked to the brim with great numbers, stood out as a rare gem.

“Victor/Victoria” is also surprisingly, forthrightly queer for its era. Thanks to the deceptions around Victoria’s gender, the film allowed Edwards to explore ideas about what it means to be a man or a woman, especially in a showbiz context where everybody is playing somebody else. What’s more, it allowed him to craft a love letter to the LGBTQIA+ performers who’ve always been present in the arts – even in 1930s Paris. Toddy is one of the most loving depictions of an aging gay man in the cinema, all warmth, affection and lonely melancholy.

“Victor/Victoria” is also surprisingly, forthrightly queer for its era. Thanks to the deceptions around Victoria’s gender, the film allowed Edwards to explore ideas about what it means to be a man or a woman, especially in a showbiz context where everybody is playing somebody else. What’s more, it allowed him to craft a love letter to the LGBTQIA+ performers who’ve always been present in the arts – even in 1930s Paris. Toddy is one of the most loving depictions of an aging gay man in the cinema, all warmth, affection and lonely melancholy.

In “Switch,” the deception that is core to “Victor/Victoria” smashes its way into the literal. A womanizer is murdered, and in the afterlife, God – who bears both a man’s and a woman’s voice – offers him the opportunity to return to Earth and find one woman who truly loves him. Yet when he returns, the devil ensures he returns as a woman named Amanda. And so for most of the film, the protagonist is played by Ellen Barkin in a wonderful comedic performance.

Here, the queerness of “Victor/Victoria” is thrown in a new, harsher light, one that underscores how ultimately rigid Edwards’ ideas about sexuality and gender could be.

If a man really did return from the afterlife as a cis woman (as Amanda seems to be), would her best friend falling for her make that best friend gay? If Amanda tried to date a lesbian, would that relationship somehow be straight? Of course not, but “Switch” often seems terrified of the notion that if gender is mutable – even in a strictly fantastical context – then so many of the “rules” we’ve built up for society will be revealed to be completely arbitrary as well. And so, Amanda’s new feminine existence is primarily defined by endless sight gags about how she can’t walk in heels – even after weeks in her new life. A man, after all, would struggle to walk in heels!

In an even darker reflection of this idea, the film’s third act begins with Amanda experiencing a sexual assault by her friend while she is drunk. To its credit, “Switch” understands what happened is a rape in a way few other projects of the time would have, but it then follows Amanda’s decision to keep the pregnancy that results from this assault, vaguely equating “womanhood” with “motherhood.” If womanhood is all about outside signifiers, then it is about being oppressed by an often uncaring patriarchy – and later serving mostly as a vessel for the next generation.

Edwards’ interest in the idea of gender mutability in both films ultimately crashes up against the idea that one’s genitalia determines most of what is true about a person. “Victor/Victoria” occasionally nods to the idea that gender is not strictly about what’s between your legs, but Victoria’s love interest, King (James Garner), spends a significant part of the movie trying to reassure himself that she has a vagina, so as to explain his deep attraction to someone he believes to be a man for much of the picture. Yes, King’s predicament makes for a very fun sex farce, but it also underlines how “Victor/Victoria” can only go so far in its ideas about gender performance. Sooner or later, you are “really” a man or a woman.

“Switch” goes even further, ending with Amanda – now having been admitted to Heaven – being offered the choice of whether to spend eternity as a man or a woman. Both sides have their advantages, she muses, but she can’t yet quite make up her mind. God assures her she has an eternity to do so, yet the implication is that once she picks, that will be that. The gender binary might be a plaything to the forces of good and evil but for us mere mortals, it is a forever prison, holding us in place. “Switch” cannot conceive of a life outside of that binary.

Both “Victor/Victoria” and “Switch” were adapted from earlier works – the German film “Victor and Victoria” for the former, the play and film “Goodbye Charlie” for the latter. In neither case were the source texts so revered that a new version simply had to be made, yet Edwards shepherded the material to the screen all the same. Across his career, he was drawn to stories about the ways in which traditional gender roles act as a straitjacket to men and women, to cis people and trans people, to gays and straights. Yet his stories never look for an escape from the straitjacket. They smile – delightfully – and say, “Ah, that’s just the way it is.”

Both “Victor/Victoria” and “Switch” were adapted from earlier works – the German film “Victor and Victoria” for the former, the play and film “Goodbye Charlie” for the latter. In neither case were the source texts so revered that a new version simply had to be made, yet Edwards shepherded the material to the screen all the same. Across his career, he was drawn to stories about the ways in which traditional gender roles act as a straitjacket to men and women, to cis people and trans people, to gays and straights. Yet his stories never look for an escape from the straitjacket. They smile – delightfully – and say, “Ah, that’s just the way it is.”

Writing in the year 2024, I would like to say that we are more thoughtful about many of these ideas. The enormously beloved pop star Chappell Roan, for instance, is a cis woman who essentially performs as a drag queen – as though Victoria Grant literally cut out the middle man, and the rise of understanding around trans and non-binary identities has helped so many people conceptualize of a gendered existence outside of an easy binary.

And yet to watch both of these films is to realize how tiny the baby steps our society has taken outside of the gender binary truly are. We are still wrestling with the questions Edwards posed in his films – and still terrified of the idea that any answer other than a binary one will unleash chaos.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.