At the heart of Cambridge University, there’s a modestly sized room with buff-colored walls and a wood beam ceiling.

It’s here where Cambridge Union—the world’s oldest and most prestigious debating society—hosts debates, which typically take place after dinner. The room comfortably seats 300 along two floors, but on a cold February night in 1965, more than 700 guests crowded into this chamber, with an additional 500 filling the nearby rooms. They arrived to watch one of the most important events in the organization’s then-150-year history: a debate between ten people on whether the American dream had been built at the expense of African Americans. Speaking in proposition was James Baldwin; in opposition, William F. Buckley.

Baldwin’s speech that night wasn’t the typical Union address; it was more of a searing sermon on the perils of white supremacy for both the oppressor and the oppressed. “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you,” Baldwin said of the country’s moral crisis. “It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians and, although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

Baldwin’s speech that night wasn’t the typical Union address; it was more of a searing sermon on the perils of white supremacy for both the oppressor and the oppressed. “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you,” Baldwin said of the country’s moral crisis. “It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians and, although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

By the end, Baldwin received a standing ovation lasting over a minute from gathered members and the majority of the votes, earning his team a landslide victory. Rhetoricians consider it one of Baldwin’s greatest speeches, as he demonstrated an unmatched ability to cut through intellectual pretense with moral clarity, exposing the contradictions of America’s racial history and its stated ideals.

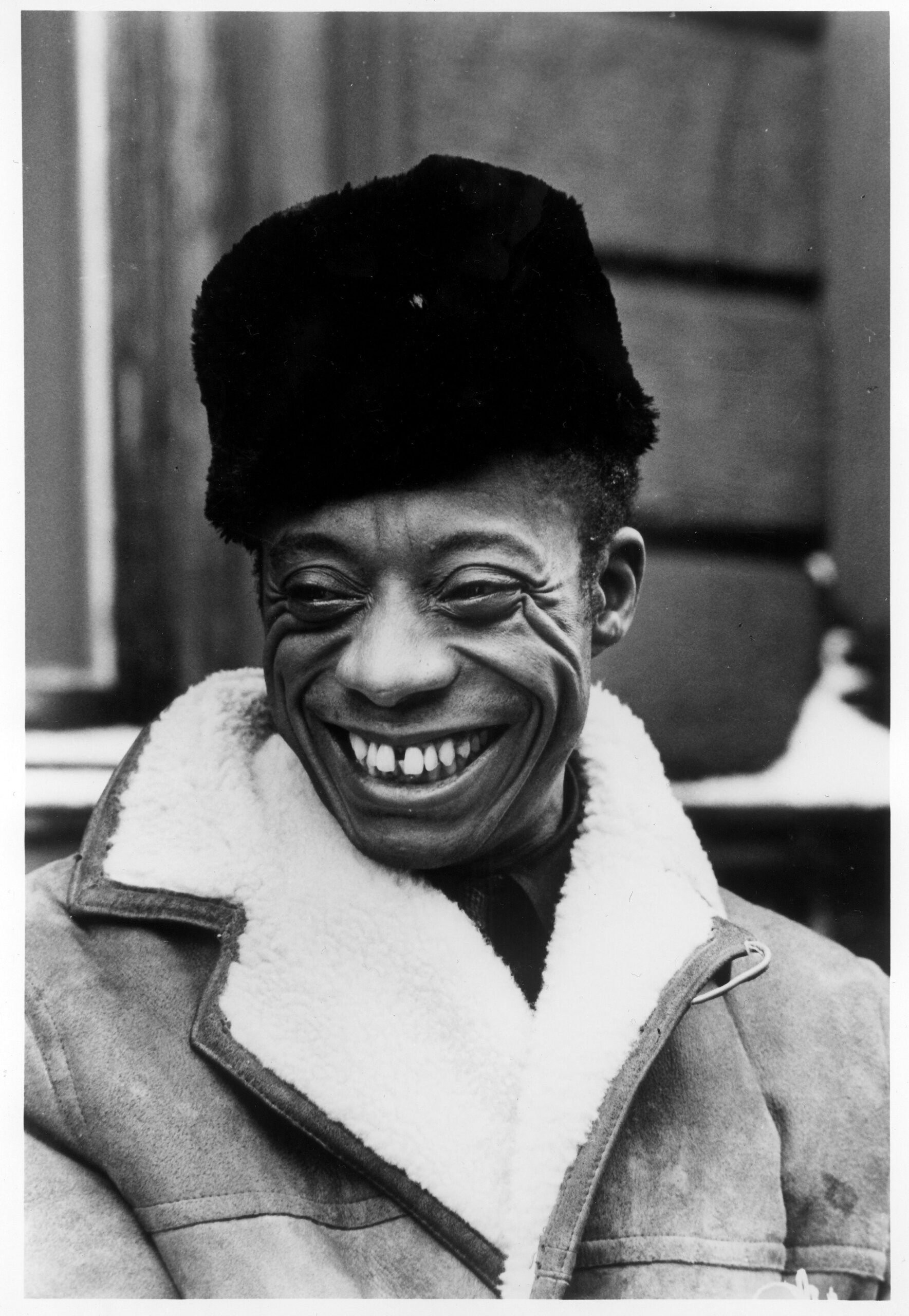

Born in Harlem in 1924, Baldwin was one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, renowned for his profound exploration of race, identity and social justice.

His writing was lyrical and incisive; his fearless candor allowed him to speak about his experiences as a gay Black man in America with unflinching honesty. He’s best known for his books: the semi-autobiographical “Go Tell It on the Mountain” (1953), the gay love story “Giovanni’s Room” (1956) and the soul-rattling “The Fire Next Time” (1963), among the many. Speaking to The Paris Review, Hilton Als once said: “One thing I learned from Baldwin, as a writer, was to use singing—the sound of singing—as prose. To make prose sound like an aria, to bring a chorus in, to take actual lyrics and expand on them.”

Baldwin’s music wasn’t confined to pages; he also knew how to sing through a less well-recognized but nonetheless important medium: clothes. Baldwin dressed with a natural sense of style that both ignored and rose above the fleeting trends of his day, allowing him to express something deeper about himself, which is why photos of him still inspire.

When he showed up at Cambridge University for that famous debate in 1965, he was in the middle of his book tour, promoting his third novel, “Another Country,” which explored taboo themes such as homosexuality and interracial love. He arrived at the chamber that night dressed as he did for his book events: wearing a sober, dark suit with moderate lapels, a pressed white poplin shirt, and a narrow dark tie finished with a well-placed dimple. The conservative, buttoned-up aesthetic conveyed a seriousness that gave his words weight. And yet, his tie was perched on top of a collar pin, which gave it a firm, beautiful arch that flowed like water from a fountain spout. This subtle bit of dash marked him as a more creative spirit than his upper-crust counterpart, the bow-tied Buckley.

When he wasn’t addressing academic audiences, Baldwin dressed with the stately flamboyance of the Duke of Windsor, somehow carried with a sense of cool. The Harlemite writer delighted in wearing oversized, distinctive eyewear and boldly patterned silk neckerchiefs jauntily tied around the neck. He was fond of lush textures, such as his velvety ribbed corduroy suit, shearling overcoat (worn with the collar popped), astrakhan hat, and fuzzy, slightly tattered terrycloth polo shirt that he sported with a knowing smirk. Even in something as simple as a short-sleeved summer shirt and flat front chinos—a matter of comfort in hot weather—Baldwin still wore chunky gold, turquoise jewelry and beautifully aged leather side-zip boots made with a Cuban heel.

In his book “Distinction,” French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that our collective notions of Good Taste are often nothing more than the preferences and habits of the ruling class. This simple theory helps explain the cultural hegemony and stability of classic men’s tailoring, as it derives its forms and practices from the English aristocracy and American bourgeoisie, whose lifestyles and dress mostly remained unchanged for much of the 20th century. Dark worsted suits will always look right with black leather oxfords because that’s what British men of a certain social class wore while doing business in London, just as Shetland tweeds and brown brogues were worn together on Scottish countryside estates, or how oxford cloth button-downs were paired with sack suits on Ivy League campuses.

Baldwin knew how to speak in the language of bourgeoisie respectability, so he dressed as needed when presenting in front of certain audiences. But as a critic of white supremacy and bourgeoisie sensibilities, he also knew how to modify his attire along the edges so that he could express his unique identity. The acclaimed writer had a checked tweed sport coat made with a single button front, hacking pockets, and wide peak lapels, which was more daring than the traditional notch variety. He wore boardroom pinstripes with holiday collars and mufflers tied with a four-in-hand; his double-breasted blazer was made with a square 4×1 configuration rather than the more typical 6×2 keystone seen on Savile Row.

Even with these flourishes, some things about Baldwin’s style marked him as unmistakably American. He often wore button-down collars, which was a style Brooks Brothers introduced at their Manhattan flagship during the early 20th century. Like the Brooks Brothers version, Baldwin’s shirts were made with unlined collar bands, which allowed his collar to rumple and shift as he moved, giving his style a natural, lived-in look that has always been a hallmark of American dress. The long collar points also formed a gentle curve like the outer edges of an ascending angel’s wings, flattering his long face and trim build. At the 1963 March on Washington, Baldwin wore a suit with two buttons neatly spaced apart on the jacket cuff—a mark of highly educated men at the time.

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Author James Baldwin with actors Marlon Brando and Charlton Heston.], NARA.

Clothing is more than adornment; it’s a social script we perform daily. While the fashion press fixates on fleeting trends, runway theatrics, and the latest creative director’s vision, the real narrative of dress unfolds in the subtle ways we signal who we are—or who we need to be.

James Baldwin understood this implicitly. His wardrobe was a form of code-switching, a sartorial dialect he adapted to navigate different worlds. In spaces dominated by polite white society, his dark tailored jackets, crisp white shirts and sober neckties softened the friction of racial bias. Elsewhere, liberated from those constraints, his style relaxed, reflecting a man who dressed as thoughtfully as he wrote—always intentional, always eloquent.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.