Marlee Matlin has won an Oscar, and she’s appeared in countless films and television shows. Yet she, too, has faced a common Deaf dilemma: how to claim equitable access to information, when one lives in a world that constantly prioritizes hearing and speech.

In Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore, director Shoshannah Stern chronicles Matlin’s life and experiences as a trailblazer in Hollywood and other majority-hearing spaces. The film contains many striking moments, but among the most powerful is one that arises near the end.

In the documentary’s distinctive style, Stern interviews Matlin on a cushy couch, both women sitting face-to-face and chatting in American Sign Language as the camera pans across their conversation. They are discussing various pieces of social knowledge that Matlin never gained direct exposure to, at least not until she faced adverse consequences. (Among them: what “domestic violence” is even called.)

As Matlin tells Stern, as English captions also appear onscreen: “Hearing people are lucky that they can overhear and have access to information anywhere they go, wherever they are, whoever they’re with.” She pauses for a second. “Deaf people only have their eyes to rely on for information.”

Right then, Stern responds gently: “That’s language deprivation.”

This scene reveals how even influential Deaf figures like Matlin are always playing catch-up, filling in knowledge gaps that hearing people have instant access to. Even with the many opportunities Matlin has had—from working with big-name directors to bringing a consistent designated interpreter along for professional engagements—she still acknowledges the impact that lack of accessible information has had on her personal life.

But what is language deprivation? Deaf communities have discussed this term for years, yet it still tends to be less familiar to general hearing audiences.

Researchers have proposed the term “language deprivation” to emphasize the importance of early language acquisition and accessible language exposure, particularly for children born deaf or hard of hearing (DHH). The critical early years of a child’s life are pivotal for shaping the communicative and socioemotional skills they will take with them into adulthood — including language development, which is foundational to numerous domains of personal and cognitive development.

Yet language development often looks different for DHH children than for their typically hearing peers. When a DHH child does not gain adequate exposure to language from an early age, they may experience lifelong consequences—from severe communication and developmental gaps to intermittent voids in social knowledge, such as Matlin experienced when she didn’t know what “domestic violence” was called. As Wyatte Hall and colleagues have suggested, language deprivation exists on a spectrum and can have assorted impacts, including syndromic language and mental health deficits as well as milder forms associated with ongoing lack of information exposure.

In essence, language deprivation stems from a mismatch between an individual child’s sensory and linguistic orientation and the prevailing communication practices of their home and school environments. Most DHH children are born to hearing families, and many of those hearing families do not learn sign language. Spoken language, on its own, is not fully accessible for DHH children.

But what about technological intervention? Although devices like hearing aids and cochlear implants can give a DHH child exposure to sound, auditory technology alone does not guarantee full language access, nor does it ensure language acquisition. DHH children are all individuals born into different circumstances, and outcomes can vary greatly. While some children may benefit from more audiological methods, others can (and do) struggle without access to a visual language.

Researchers highlight how DHH children’s (and adults’) lack of language exposure is tied to other ongoing issues, such as limited opportunities for “incidental learning,” the contextual knowledge that hearing people gain when they overhear the spoken conversations around them. Deaf children who grow up in predominantly hearing-and-speaking environments often miss out on such incidental information—not because they are incapable of learning, but because of this mismatch in language use and sensory modality.

Among the other impactful scenes in Stern’s documentary is one that shows what inaccessible language can look like, how challenging it can be for a Deaf person to learn anything incidentally in a nonsigning environment.

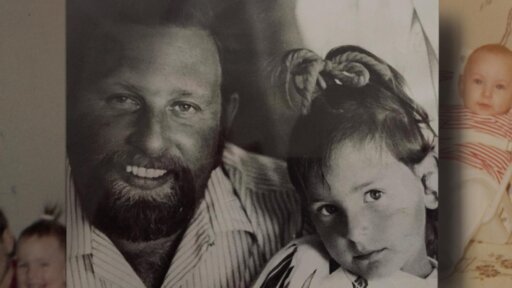

Marlee Matlin and her brothers in a scene from Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore (2025).

At one point earlier in the film, the filmmaking team accompanies Matlin into a social gathering with her hearing family members, none of whom sign fluently (or really very much). While everyone stands talking in the kitchen, we see Matlin ask “What?” Her family’s spoken conversation keeps stumbling forward, largely without her participation.

Suddenly, the film acquires an unusual hyperattention to sound. In old-school yellow closed captions—distinct from the style used for most other captions—disparate noises start to whirl across the screen. Laughter. Dishes clinking. The straight-up repeated caption [INDECIPHERABLE]. The cinematography emphasizes the hearing world’s attunement to auditory information, blended with tongue-in-cheek commentary about how absurd these sounds can feel.

Matlin’s eyes are darting back and forth onscreen. Soon, she is sitting on the couch as her hearing companions chatter, their [MUDDY VOICES] and [EMPTY VOWELS] still sweeping over her head.

When she briefly makes eye contact with the camera, the effect is undeniable: frustration, mixed with an utter lack of surprise. Matlin has been here before.

Many DHH people have been here, too, in their own ways. Among Stern’s gifts as a director is her ability to claim the language of film—from creative captioning to audiovisual design—to emphasize the inherent thorniness of communication.

In the documentary’s Deaf subjectivity, language deprivation and lack of language access are real and tangible challenges. They are phenomena that have shaped Matlin’s life. (In addition to language deprivation, Deaf people commonly discuss the consequences of “dinner table syndrome,” or the feeling of being left out around a rollicking table of spoken conversation.)

The film shows Matlin wrestling with her own upbringing and language access. She explains how she was the only Deaf person in her family, as well as the youngest. She constantly had to ask other family members what was happening. She brought comic books to read at the dinner table, trying to ward off boredom.

“But at that time, in their defense,” she says, “I didn’t know just how important communication was. I couldn’t pinpoint the problem.”

Stern’s film illustrates pieces of that problem. Through pulling the viewer into Matlin’s personal journey, and through prioritizing visual storytelling, this documentary emphasizes the importance of accessible communication.

As Matlin explains to the camera, she loves her hearing family. Her parents did the best they could. She just wishes they’d had more information—all of them, including herself.

Today, the research-based evidence keeps mounting: bilingual approaches to Deaf education have enormous benefits. Even if hearing parents do not become fluent in ASL, their efforts to incorporate signing into shared home life can still have positive impacts for their DHH children, regardless of which decisions they make about speech and technological intervention. And ensuring visually-rich schooling environments can also empower DHH children, whether they attend a Deaf school or a mainstreamed school with accommodations such as ASL interpreting.

Though Matlin is a singular figure, Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore also points to a more general history shared by many Deaf people: that of growing up alone, of feeling isolated by inaccessible communication. Yet life is better when we aren’t alone, when we can share our language with those closest to us. As mainstream knowledge about ASL continues to grow, more of us, both Deaf and hearing, stand to benefit from more multimodal and multilingual ways of communicating.

In sharing her own stories about language access, Matlin is continuing to open new paths for social change.