404 Not Found

On Aug. 12, FRONTLINE producer Martin Smith, his co-producer Marcela Gaviria, and cameraman Scott Anger set out on a two-month journey that will take them from London to the Persian Gulf to Pakistan and Afghanistan in an effort to find out what has become of Osama bin Laden's terrorist network, Al Qaeda, since the U.S. launched its war on terrorism. In the weeks ahead, we'll be posting regular email dispatches from Smith and Gaviria as they report back to us on their progress, offering an unprecedented behind-the-scenes perspective on a FRONTLINE documentary in the making. Smith's report will air in mid-November.

"Don't Go to Timargarha."

1-2 September, Drosh to Timargarha

from Marcela

Gaviria

| |||

For over a decade Gaviria has field produced documentaries for PBS, BBC, National Geographic, and CBS News. Currently working with Martin Smith on FRONTLINE programs, they co-produced "Medicating Kids" and she field produced two post-9/11 reports: "Looking for Answers" and "Saudi Time Bomb?" | |||

The road from Chitral to Drosh swings east hugging the Shi Shi River on its way. About twenty miles south of Drosh, the river is cut in two by a tiny island that holds a beautiful old fort built in 1919 by the British. Martin has found one footnote about this place in some book, and is determined to make it there by nightfall.

After three nights sleeping in grim guesthouses, we hope to take a break from the sewage canals, soiled sheets and malodorous bathrooms. We cross a rickety bridge and pound on the door of the Nagahor Forte hoping it is still a guesthouse for weary trekkers and journalists.

It takes a good long time before someone opens the door. The place has not seen many visitors since Sept. 11. There is no running water and electricity. The place is practically abandoned, but the grand wrap-around views of the valley and the stark mountains fill the place with magic.

We sit on the side of the fort and watch the powerful waters of the Shi Shi well up hundreds of feet below. The river winds past the terraced layers of corn fields and cuts through the mountains, which stack up against each other like cutouts. It is the most breathtaking view of our journey.

Without water or electricity, dinner takes four hours to prepare. We haven't had a bite to eat since 7 a.m., and we wait impatiently, counting stars. Martin sees three falling stars. I spot the Milky Way and the Northern Star. Scott is more fixated on filming the lights of cars crossing the Hindu Kush at a distance. At midnight, after countless cries for food, Martin calls it a day and heads for bed on an empty stomach. The rest of us figure we've made enough of a fuss and wait for another hour until a feast of stir-fried vegetables (sabzi), lentil stew (dhal), grilled chicken (tabak), and bread (chappatis) is served to us in the garden. Pakistani food is much like Indian food, except much oilier and less varied. I am tired of it by now, but at this hour it tastes great.

Our break from work lasts only one evening. In the early morning hours we head back to Dir, where we hope to shower and get back on our beat. Again, we camp out at the Al-Manzer hotel while Shameem brings possible interviews -- a school teacher, a doctor, a religious scholar -- to our roof-deck studio. It seems that today, we are again stuck listening to the usual: Islam means peace, Al Qaeda is an invention of America, Sept. 11 was orchestrated by the CIA to create an excuse to kill all Muslims.

The doctor turns out to be the most candid of the bunch. He tells us that George Bush is a dog. When he hears we plan to head to Timargarha after lunch he balks.

"Whatever you do, don't stop at Timargarha."

So, of course, that is exactly what we do.

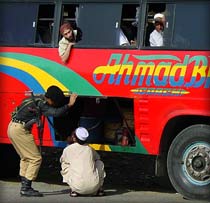

A few miles before we reach Timargarha we hit the first checkpoint. An anxious border guard pulls us aside and checks our papers. He tells us there is trouble up ahead and says that it is unsafe to stop and unsafe to continue. It's a confusing Catch-22. Shameem isn't translating, either. The guard talks rapidly and most anxiously. Scott is rolling as Martin asks what is happening in the town.

| |

Frontier Corps search vehicles at a checkpoint in the Northwest Frontier Province near Dir. (Photo by Marcela Gaviria) | |

"It is too dangerous," the guard says. "There are demonstrations on the street. You might get hurt. There is much hatred for Americans. You must get out of here. "

Shameem is so worked up he only translates every 20th word. Our nerves are starting to fray. Martin, Scott and Shameem get out of the van to sus out the situation. As usual, I am forced to stay inside.

Faizal, our driver, is close to panicking. His lip actually trembles as he implores me to convince Martin to continue on to Peshawar without stopping at Timargarha. For the first time, I am scared.

Faizal riles off a million questions, "What will happen if they beat you up? Why are you doing this? There is no point risking your life. Who will pay for my car if they vandalize it?"

I explain that we don't have much of a choice but to head onwards. Dir is unsafe, and we have to cross Timargarha if we are to make it back to Peshawar.

The van falls silent as we get closer and closer to the town. I have my finger on the speed dial of my satellite phone, hoping to make a quick call to a resourceful contact in Islamabad if anything should go wrong. The phone is useless in the car -- it only works if you point it at the satellite up in the sky -- but I hold on to it like a little security blanket.

We are all vigilant. It seems that every man squatting on the street might be holding a hand grenade and that every carload that passes us might be a group of jihadists hoping to shoot us down. It's this kind of fear that breeds blind prejudice.

We have our usual escort. Six armed guards in front, six behind. But this is rarely of any consolation. The guns make all of us nervous.

Funny enough, the minute we reach Timargarha, we are back at ease. Martin believes that the best way to know if you are in hostile territory is to look people in the eye, nod, and see what kind of response you get. If they stare blankly back, you may have to wonder. But people in this town are responding to our overtures, and some even smile as we pass by. The town is bustling about like it would on any old Monday. There are no signs of demonstrations. We are perplexed.

We are whisked off into a back courtyard of the Continental Hotel, a walled fortress in the middle of town where we can call some of the local contacts in our Rolodex. Soon a few facts, however confusing, start trickling in. The demonstrations were not organized by angry locals demanding to know what happened to the 7,000 jihadists that went to Afghanistan never to return, but by a handful of family men protesting the imposition of electricity meters in their houses. What else is new.

The cops insist that there is a different story. Once source tells us over the phone, "Listen to the cops." It's a hard one to read.

We don't overstay our welcome. In truth, we never really knew if we were in danger or not. It's hard to get a straight answer about the simplest things in this country. Especially when Shameem is too nervous to translate.

It's late by the time we leave Timargarha and we still have four hours to go on the road. The road to Peshawar seems far less carefree and beautiful than it did a few days back. It is also hard to doze off since the van jerks at every twist in the road.

|

· My Baffling Question/An Obedient Dissident · The Wedding Party · Arriving in Yemen · Inside the Kingdom · Indomitable · A Circle of Trust · The Next Big Get · The Madrassa · A Little Noticed Gun Battle · The Plight of Women · Frustrations · Faisal Town · Road to Nowhere · An American Informer · Don't Go to Timargarha · Border Town · In the Northwest Frontier · Prisoners' Dilemma · On the Road to Chitral · Rumors and Half Truths · Bombs or Dust Devils · Paranoid in Peshawar · We Believe in God · Nuclear Neighbors · Old Hash · A Firehose of Information · Dubai to Karachi · Like an Elephant Chasing a Mouse · On Board the Algonquin · HMCS Algonquin · Faces at a Dubai Mall · Armchair Jihadists · Zubaydah Is Dead · Preparations |

We soon bump into another cricket game on the roadside. Were it not the most evocative image for miles perhaps we'd move on. But it's dusk, magic hour, and the day has been pretty much of a lost cause. It would be nice to secure one little sequence.

Scott jumps out and sets up his tripod. I get rebellious and abandon my van confinement so that I can point my sat phone to the sky in hopes of making a call. Martin sits against a tree and watches the sun set over the kids and their wickets below. The bliss doesn't last long, however. The police escort have caught up with us ... again.

"You cannot shoot the cricket game. We have orders. You cannot get out of the car," says one officer.

We try to explain that we cannot make a film unless we are allowed to shoot images along the way. We ask why we are not allowed to shoot. We see no danger. We tell him that high-ranking officials in Islamabad have given us permission to shoot in this region. But the guards are getting more rigid by the second, and I am close to throwing a strop. The light is dropping quickly and soon it will be too dark to film.

"Do you understand me? We have permission to film here. Look at this letter." I'm fuming. "Do you want me to call up Brigadier Cheema or General Musharref and have them explain?" Nothing seems to work and I am now turning into an ugly American.

I wish I could explain. I have deadlines and a budget and we've come such a long way. We may never see another cricket game at magic hour.

A couple dozen people have now gathered around us to witness the exchange. An American woman is giving orders to a man in uniform. Martin takes advantage of the situation to record a standup. That really irks the guards, who move in and pull Martin back into the van by one arm.

By that time, we are all too tired to protest.

< (previous dispatch) · (next dispatch) >

web site copyright 1995-2014 WGBH educational foundation