‘A Different Kind of Story’: Brad Lichtenstein and Yoruba Richen on Making ‘American Reckoning’

February 16, 2022

Share

For years, filmmaker Yoruba Richen had been fascinated by a largely overlooked chapter from the civil rights movement: that of the Deacons for Defense and Justice.

Members of the Black-led armed resistance and self-defense group had protected marchers and enforced a 1965 NAACP-led boycott in Natchez, Mississippi — a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity. The effort resulted in white business owners agreeing to hire Black workers, the city pledging to hire Black police officers and the desegregation of multiple public institutions.

Yet the Deacons “had been basically written out of our history books,” Richen said. “And of course, part of erasing their story serves to erase the history of white terror that they were fighting against.”

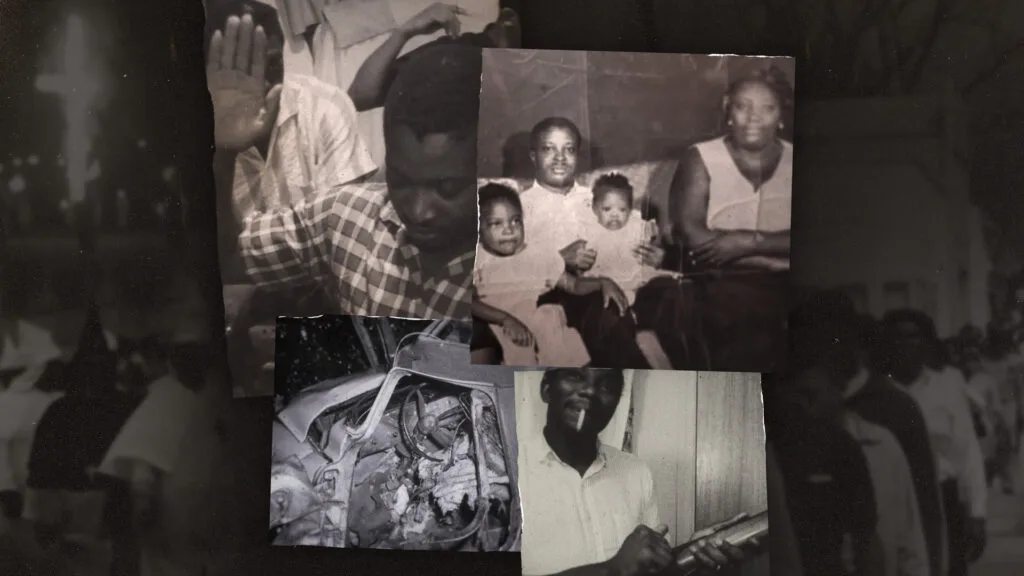

So when Richen’s friend and fellow filmmaker Brad Lichtenstein asked in 2016 if she’d be interested in partnering with him on a documentary he was working on, about the unsolved 1967 murder of a Black civil right activist, Wharlest Jackson Sr. — and said the film would involve rich archival footage from Natchez in the 1960s, as well as the Deacons — she jumped at the chance.

“Those two things are what sealed the deal, like, ‘Oh, this is going to be a different kind of story about a civil rights murder and the search for justice,’” Richen said.

That story, American Reckoning, premiered on PBS Feb. 15 from FRONTLINE and Retro Report, with support from The WNET Group’s Chasing the Dream initiative, and is now streaming online, in the PBS Video App and on FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel. It’s the documentary component of Un(re)solved, a multiplatform experience grappling with America’s legacy of racist killings.

The film team wanted to illuminate both the fatal car bombing of Jackson — the treasurer of the Natchez chapter of the NAACP, who had just become the first Black man in his new role at a local tire company — and the broader context of what was happening in Natchez at the time. To accomplish that, the documentary draws on rarely seen 1960s footage from filmmakers Ed Pincus and David Neuman, made available through the Amistad Research Center.

“We’re just so lucky to have had all that,” Lichtenstein said, adding that, as the film was taking shape, the executive producers of the Un(re)solved project, Dawn Porter and FRONTLINE executive producer Raney Aronson-Rath, encouraged him and Richen to lean into the archival footage.

The result is a unique, multilayered film about white terror and Black resistance. “We were able to bring out the Natchez story and what happened in Natchez, Wharlest’s role in it, the family’s experience of it, and have that balance,” Richen said.

Getting Started

The road to American Reckoning began with the late civil rights icon U.S. Rep. John Lewis, whom Lichtenstein had known since he was a 15-year-old high school student in Atlanta volunteering on Lewis’ 1986 Congressional campaign.

Decades later, Lewis’ staff pointed Lichtenstein toward the now more than 150 names associated with the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act, a federal effort the late U.S. representative sponsored to reinvestigate civil-rights-era killings that became law in 2008.

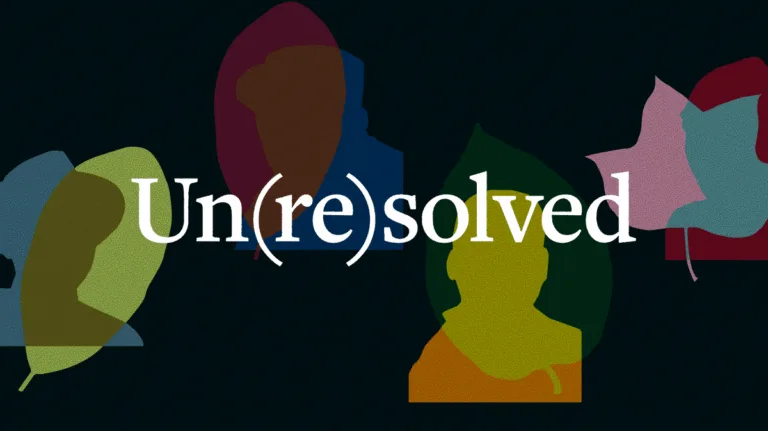

Lichtenstein zeroed in on Jackson’s case, in part due to the existing archival footage. He began talking with journalists and filmmakers involved with the Civil Rights Cold Case Project, including David Paperny, Jerry Mitchell, Robert Rosenthal, Peter Klein, David Ridgen — and Stanley Nelson. Nelson, until recently editor of the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday, Louisiana, across the border from Natchez, had investigated the Silver Dollar Group, a Ku Klux Klan offshoot whose members the FBI named as suspects in the murder of Jackson and five others in the 1960s.

When Lichtenstein first visited Natchez in 2014, his only official appointment was a meeting with Nelson, who eventually would end up working on the film. But during that visit, Lichtenstein took a chance: He dropped by the house of Jackson’s son, Wharlest Jackson Jr., knocked on the door and explained what he hoped to learn.

“I said, ‘just, you know, give it some thought,’ and I would just hang out at the park, and then he could come by if he was interested, and he did a few hours later,” Lichtenstein said. “And that was kind of the beginning.”

Over time, Lichtenstein, Richen and the film team spoke with additional members of the Jackson family; as well as Charles Evers, the late Mississippi NAACP leader whose brother Medgar Evers was assassinated by a white supremacist; Rep. Lewis; FBI and Department of Justice sources; former members of the Deacons; Natchez residents and others.

“We connected with a local activist and historian who’s in the film, Ser Clifford Boxley, and he was really key in introducing us to Deacons,” Richen said. “I find that, in the films that I make, people are eager to tell their story because their stories haven’t been told.”

Through archival footage and first-person accounts, the film sheds new light on how the Deacons gained the capacity to, in Boxley’s words, “hit the street” and “checkmate” the Klan. The Deacons provided armed security and protection for civil rights marchers. They also operated as enforcers within the Black community, as the NAACP led its boycott in Natchez.

Read more: “How Rarely Seen Archival Footage Brought a Civil-Rights-Era Story to Life”

“We have the right to discipline our own people,” Charles Evers, the NAACP leader, says in archival footage that appears in the film.

“It wasn’t just having a boycott, but it was enforcing the boycott, right?” Richen said. “You had to make sure that your own people did not break the boycott. That’s a part of it, too. And it’s not always pretty, in terms of how that enforcement works.”

Centering the Family

By the time production on American Reckoning began, Jackson’s wife, Exerlena, who had been a civil rights activist alongside her husband, had died. Yet she’s still a key voice in the documentary, thanks to personal footage shared by her family. Exerlena Jackson speaks extensively about her experiences on the front lines of the civil rights movement in Natchez — including being locked up in the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman — and her husband’s murder.

Filmed by a family member, the recordings of Exerlena Jackson provided “a way, just kind of internally, to memorialize the story and what she had been through,” Lichtenstein said.

Receiving the footage was a “game changer,” Richen said, allowing the film team to show that “Exerlena was also part of the movement” and was “out there marching,” even though “she, like so many women, doesn’t get the credit.”

Richen and Lichtenstein said they worked hard to build trust with the Jackson family. “I think, like so many of these relationships that get built in documentary filmmaking, it’s really about showing up, and it’s about trying to listen really carefully to the family,” Lichtenstein said — including navigating how to depict Jackson’s violent death.

The film team asked the family about using “a very gruesome photograph” from the FBI case file that had been taken after the car bombing and published in Jet magazine. “I thought that there might have been an interest in having that photo out there,” Lichtenstein said, recalling Emmett Till, the young victim of a brutal, racist murder whose mother insisted on an open coffin for his funeral.

But when he asked, he learned that the Jackson family was upset by the publication of the photo and that “for years, Exerlena and then [her daughter] had hid any copy of that photo, so Wharlest’s grandkids would never see it,” Lichtenstein said. “So, we ended up not using it.”

Ultimately, the film team’s conversations with Jackson’s family drove home the thin line between past and present.

“What struck me really emotionally was, I did the interview with [Jackson’s niece] Cheryl Glover, and we think, Oh, this was so long ago,” Lichtenstein said. “But [Jackson’s] sister was just upstairs. She’s in her 90s. She’s alive, you know? … This is only a generation [away].”

Connecting the Past and the Present

The original investigation of Jackson’s murder ended with no arrests or prosecutions. So did the reinvestigation, opened in 2007. In fact, of the more than 150 cases reopened under the Till Act, all but 21 have now been closed, without the Department of Justice bringing any new charges.

That means “there still are no official answers” in Jackson’s case, Richen said.

But as the documentary chronicles, Stanley Nelson’s reporting, which was done in collaboration with the Cold Case Justice Initiative at Syracuse University and relied heavily on FBI files from the 1960s, suggested the involvement of Red Glover, a now deceased Klan member and leader of a KKK offshoot called the Silver Dollar Group, who worked at the same tire company as Jackson.

American Reckoning explores the circumstances that allowed the Klan to operate in plain sight, including what Lichtenstein and Richen described as “white denial.” In the film, former Natchez alderman Tony Byrne describes having thought of Klan activity as “a bunch of people running around in sheets,” saying he “didn’t think it was that serious.”

Of Byrne’s comments in the film, Lichtenstein said, “He can walk away any day he wants and not be threatened. But Cheryl Glover can’t. [Jackson’s daughter] Denise Jackson Ford can’t. And that’s a significant difference in the way we live in America.”

In making the documentary, Richen and Lichtenstein grappled with many echoes of the past in the present.

“It’s so easy for people to dismiss these moments, like George Floyd: Well, that’s a bad police department,” Lichtenstein said. “Or Michael Brown: Well, you know, Ferguson was a suburb with a history of issues. Or Wharlest Jackson: Well, that was back at the time, with the Klan,” Lichtenstein said. “These things are not separate and isolated. They all come out of the fabric and system that was created here in America and that we have to reckon with.”

That’s why, he said, the film is called American Reckoning.

“As a white filmmaker, making this film is an exercise in trying to surface awareness that I might not have had before of my own privilege,” Lichtenstein said.

Both Lichtenstein and Richen said they hope the film will deepen public knowledge of nuances in the civil rights movement as America’s reckoning with racism continues.

“I hope people will have a new understanding of the different strategies of the Black freedom struggle,” Richen said. “It’s been sort of reduced to Martin Luther King and nonviolence, but it’s a longer movement and a movement with many different strategies, and the Deacons were a part of that.”

Lichtenstein and Richen said they also hope the film sheds light on the contributions and sacrifices of relatively unknown “foot soldiers” in the civil rights movement, including Jackson himself.

And, of course, his family.

As Richen said, they have been “looking for justice and searching for justice for so long.”

American Reckoning is available to stream in full below, as well as on the PBS Video App and FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel.

The film is the documentary component of FRONTLINE’s broader Un(re)solved initiative, which also includes a web-based interactive experience, a traveling augmented-reality installation and a podcast series. Taken together, the multimedia project tells the stories of more than 150 people, including Wharlest Jackson Sr., whose civil-rights-era killings have gone unsolved or unpunished, and it explores the limitations of a federal effort to reexamine these cold cases under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act. Explore Un(re)solved now.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.