|

|

|

by Peter Tyson July 13, 1998 Now that the expedition's dreams have been realized - retrieving four black smoker chimneys from the seafloor - there's time to take a breather and tell you about life on board the ship. There's a sign in the R/V Thomas G. Thompson mess that reads, "Don't dump anything over the side." Well, I've dumped just about everything over the side. You'd do the same, believe me. You can't help it. Just about everything you're familiar with gets thrown off as soon as you board ship. Among them: ¤ Physical balance. This is the first thing you lose. You feel like a newborn fawn trying to get its legs—and look just as ridiculous. It's harder for tall people like me, whom the slightest tilt of the ship leaves grabbing frantically for support. For someone who likes solid ground under his feet, as I do, this comes as something of a shock, like a sudden return to gawky adolescence.

¤ Sense of time. Excuse me, I should have said 17:00. Ship time is on the 24-hour clock, which for me always requires an extra step, like calculating what a meter is in feet. But telling time is the least of one's worries. On a research cruise, your whole sense of time is tossed out the porthole. The workday is not 9 to 17:00; it's around the clock. In some ways, it's like vacation: days of the week become meaningless, the calendar date utterly forgotten. ¤ Sleep schedule. Need your full eight hours? Forget it. You're lucky to get four hours at a stretch on this ship. Each of us has been assigned a watch. Mine is 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. to 8 p.m., every day. At 2 a.m., you'll usually find more people up than not; at noon, you'll see bleary-eyed ROPOS guys coming off their midnight-to-noon shift. Like Farley Mowat studying his wolves, you learn to nap round-the-clock. ¤ Familiar sounds. Like silence when you sleep? Hah! My cabin is up in the bow, the Home of the Bow Thrusters. When ROPOS is on duty, these neo-propellers are, too, helping to keep the ship precisely positioned. In the first days, they kept me precisely awake. At their calmest, the thrusters resemble a New Age concerto, with an operational sound like a distant wood-chipper on a summer day, the percussive torque of the machine as it turns, and the mournful thrusting itself, culminating in a whoosh of water. At their busiest, you feel like you're stuck inside an outboard motor at full throttle.

¤ Sense of family. For the few weeks you're on the ship, you have a new family. John Delaney might as well be dad, Debbie Kelley mom, and the other 30-some members of the scientific party and the 21 crew your extended family. Minus the squabbles, of course. "This ship isn't big enough for the two of us" isn't an option when you're 200 miles out to sea, so best behavior is the order of the day. Friendships form that might last long after the cruise ends on Saturday, when, as Delaney wistfully put it to me today, "this group that will never again be together dissipates like smoke." ¤ Sense of place. Where you live is much deeper than where you reside. I live in a house in Arlington, which is outside of Boston, which is in Massachusetts, which is a day's drive from my wife's family in Buffalo and my folks in Philadelphia. Here, where we live is the Thompson. You can walk 270 feet from the bow to the stern, a hop and a skip from starboard to port, or up and down six flights of stairs between the laundry and the bridge. That's it. It's hard to feel a sense of place when you're in the middle of an ocean.

¤ Sense of reality. At home, the New York Times is like food: I gotta have it everyday. It's a cherished pleasure, and it satiates a daily need I have to know what's going on in the world. A friend at NOVA has been sending me news bits from the Times, but somehow the events they describe are as meaningless here as whether today's Monday or Thursday. Perhaps it's the knowledge that there's not a darn thing I can do about anything out here anyway. I miss caring, but I don't miss other artifacts of the real world: ringing telephones, snarled traffic, ants. ¤ Familiar nature. I like ants actually, but not the big black carpenter ants I discovered chewing up my foundation just before I left home. Here there are no bugs. I haven't seen a single insect since we left port. Nor a single green leaf. The only vaguely familiar wildlife has appeared off the stern: winging petrels, a frolicsome pod of dolphins, a seal darting after squid drawn to our deck lights at night. Otherwise it's waggly tubeworms, bacterial mats, and other outlandish creatures of the abyss. ¤ Sense of self. When you don't know anybody, you can be anybody you want. Generally I prefer being myself. But when you dump everything overboard, albeit unwittingly, you're in danger of dumping a solid sense of yourself over as well. My cure? Pull out photographs of my wife and children, who ground me stronger than any black smoker rooted to the seafloor. Check back soon to find out what scientists are learning about the black smoker chimneys pulled from the seafloor, and their bizarre attendant life forms. Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. The Tug of the Thompson (June 23) The ROPOS Guys (June 25) In the Juan de Fuca Strait (June 27) Special Report: A Visit To Atlantis (June 29) Dive 440 (July 1) Rescue at Sea (July 2) What's Your Position? (July 4) Phang! (July 5) 20,000 Pounds of Tension (July 8) Four for Four (July 11) Thrown Overboard (July 13) Was Grandma a Hyperthermophile? (July 15) Swing of the Yo-Yo (July 18) The Mission | Life in the Abyss | The Last Frontier | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Table of Contents | Abyss Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated October 2000 |

Sense of balance, sense of fear.

Sense of balance, sense of fear.

Through the far wall: the bow thrusters.

Through the far wall: the bow thrusters.

The view from the back porch.

The view from the back porch.

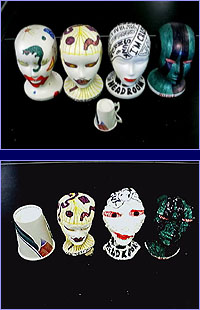

Styrofoam wigheads before and after diving to 7,000

feet. Note coffee cup in both pictures for scale.

Styrofoam wigheads before and after diving to 7,000

feet. Note coffee cup in both pictures for scale.