|

|

|

by Peter Tyson Japan's akoya oysters have been preëminent among cultured pearls ever since Kokichi Mikimoto first established the industry in the early part of this century. But since 1994, something has been killing off the akoyas of Ago Bay, the heart of Japan's cultured-pearl business, and elsewhere in the country. Experts attribute the initial oyster deaths in 1994 to "red tide," a bloom of microscopic, toxin-producing animals in the ocean that proved deadly to the oysters. Named for the discolored water created by the presence of the minute creatures, red tides are short-lived events. Yet the oyster deaths continued long after the 1994 tide had dissipated; in fact, they increased. In 1996, the most recent year for which figures are available, 150 million akoya oysters perished, according to Devin Macnow, executive director of the Cultured Pearl Information Center, a trade group in New York City financed by the Japan Pearl Exporters Association.

A Gem of an Enigma Even after several years of scientific investigation, the specific cause of the disease remains a mystery. The illness first makes itself known when the abductor muscle, which holds the two parts of the oyster shell together, turns a reddish-brown. Ultimately, eight out of ten affected oysters die from the affliction, which so far has only affected akoya oysters. Even isolating apparently healthy oysters has had no effect: the disease seems to ferret them out.

Many remain skeptical of the virus theory, however. "To me, the problem has always been extraordinarily simple: it's pollution," says Fred Ward, a gemologist and author of a book on pearls (see History of Pearls and Culture of Freshwater Pearls). "I would never attribute it to an unidentified mystery disease. It's a multitude of pollution-related problems." When Kokichi Mikimoto first began growing oysters in Ago Bay early in this century, he says, the bay was close to pristine, with few people living around it and no industry. Today, however, the heavily populated bay faces a continuous assault, he says, from industrial and automobile pollution, pesticides and herbicides, household detergents and other chemicals, even raw sewage. "Until you eliminate those and give it a chance to recover, there's no hope," Ward concludes.

Macnow, for one, takes issue with the idea that pollution is to blame. For one thing, he notes, akoya oysters share the same waters with other Japanese aquaculture products, including shrimp, other oysters, and fugu, or blowfish, which is highly sought after for sashimi, the Japanese dish of thinly sliced raw fish. "If there was a significant amount of pollution," he says, "this would have hit the other industries, which so far have not been affected." He also notes that 20 percent of those oysters that get the disease survive and go on to produce a decent pearl.

Whether the cause is a natural virus, a pollution-caused disease, or something entirely different, the Japanese have to come up with something fast to save the akoya oyster. According to Torrey, Japanese scientists claim that they recently isolated the virus. They believe it cannot travel more than 330 feet underwater, and so to combat its spread, they plan to thin the densities of akoya oysters in afflicted areas. Eventually, they maintain, akoya oyster populations should return to health, probably by the year 2002. Thinning may solve the problem, Müller says, because lower shell density usually results in a higher quality pearl. "In effect, the farmers will be getting more with less," he says. Others feel more radical solutions are required. Ward advocates moving oyster farmers out of the hardest-hit areas, such as Ago Bay, even as he concedes that few clean bays remain in Japan in which to relocate the farmers. Even without the disease, he says, the estimated 130 pearl farmers currently vying for space within the bay would represent an enormous strain on the system.

If so, it is conceivable that the preëminence of akoyas is over. Indeed, Torrey says it's possible the Japanese akoya industry may never recover to what it was in Mikimoto's heyday. "Many people believe the Japanese will become more processors and marketers of pearls than producers," he says, "while concentrating only on producing higher-quality, large-sized akoyas." Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. What's Killing the Oysters | Culture of Freshwater Pearls How Many Pearls? | History of Pearls | Resources Teacher's Guide | Transcript | Site Map | Pearl Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

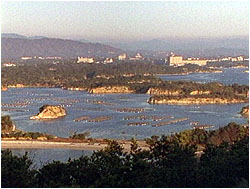

For decades, oyster farmers in Ago Bay, Japan, had

everything to smile about, but recently the tide has

turned.

For decades, oyster farmers in Ago Bay, Japan, had

everything to smile about, but recently the tide has

turned.

The harvest of akoya pearls such as these raised in

Ago Bay has mysteriously plummeted in recent years.

The harvest of akoya pearls such as these raised in

Ago Bay has mysteriously plummeted in recent years.

Pearl farmers haul out their oyster cages in Ago Bay.

Pearl farmers haul out their oyster cages in Ago Bay.

Ago Bay alone harbors an estimated 130 akoya-oyster

farmers.

Ago Bay alone harbors an estimated 130 akoya-oyster

farmers.

In the wake of falling harvests, akoya oysters may

get a bit of breathing room.

In the wake of falling harvests, akoya oysters may

get a bit of breathing room.

Will Japan become a nation of pearl processors and

marketers rather than producers? Only time will tell.

Will Japan become a nation of pearl processors and

marketers rather than producers? Only time will tell.