Explainer: Understanding Auctions vs. Private Sales

ROADSHOW talked to a cross-section of our experts to learn more about the detailed differences between selling your item through a private dealer versus at public auction.

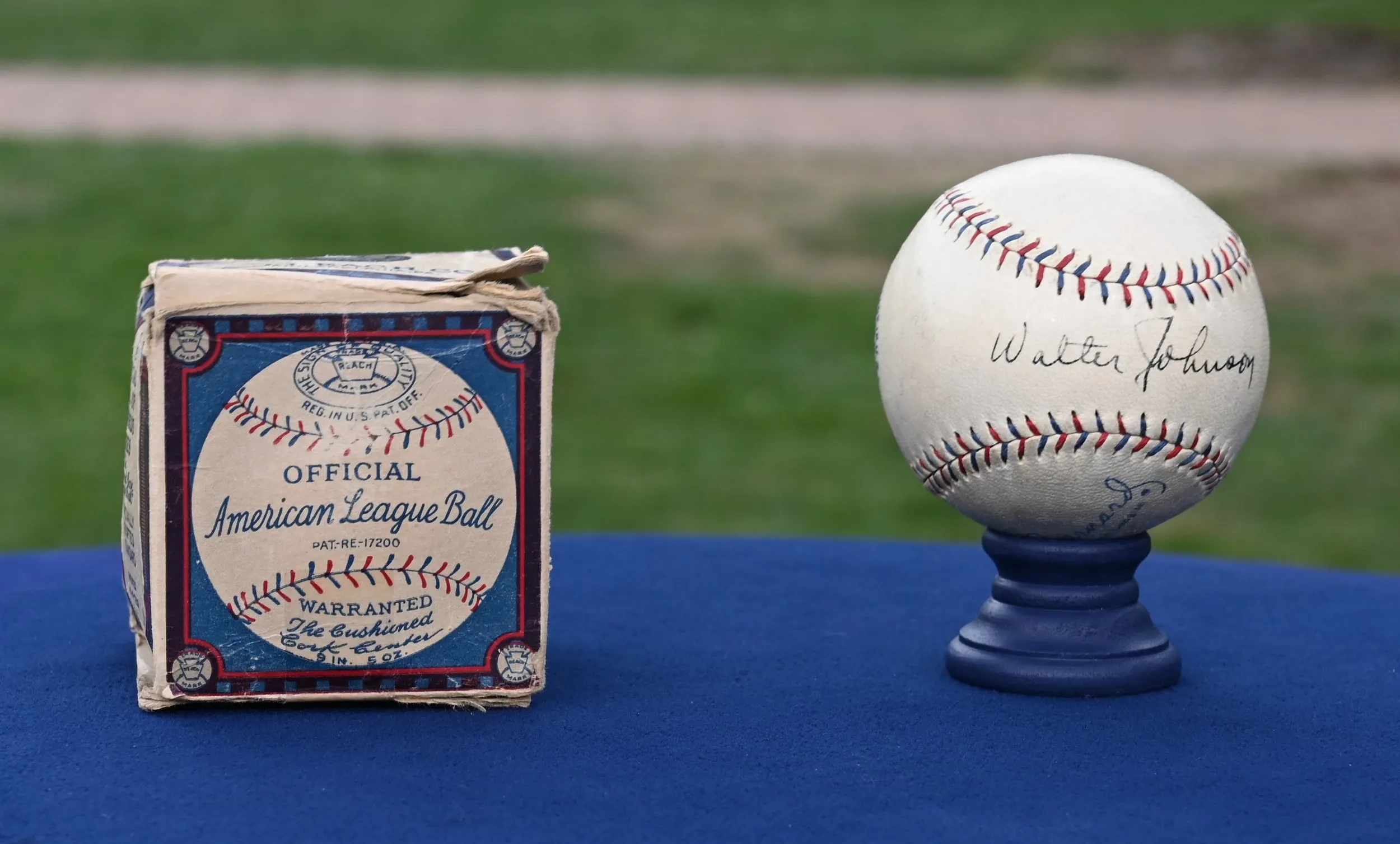

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s June 2022 visit to Filoli in Woodside, California, Sports Memorabilia appraiser Leila Dunbar found a remarkable baseball signed by Walter Johnson, who played for the Washington Senators from 1907 to 1927. Calling the pristinely autographed baseball “the best known of its type,” Dunbar ultimately put an auction estimate of $60,000 to $80,000 on the ball, concluding that it might even sell for $100,000.

A year later the owner called Dunbar asking for help selling her Johnson-signed treasure. While Dunbar only handles written appraisals through her company Leila Dunbar LLC, she helped the guest decide how to approach her two basic options: try to sell the ball privately through a dealer, or sell the ball publicly at auction.

Deciding how to go about selling a prized possession can be a daunting and confusing task, as both public auctions and private sales come with their own benefits and risks for both the seller and those facilitating the sale.

To better understand the steps involved and the nuances of each process, we spoke to several ROADSHOW appraisers across a range of categories to get their expert help in explaining the key points of both.

Deciding how to go about selling a prized possession can be a daunting and confusing task — both public auctions and private sales come with their own benefits and risks.

Selling Privately: Working with a Dealer

One of the primary benefits of selling your item through a private dealer is that for the most part, the sale is an instant transaction. In this arrangement, the dealer is essentially a “middleman” who purchases your item from you, then puts in the work of authenticating and selling that item to a third party for a profit.

As Books & Manuscripts appraiser Devon Eastland, a senior specialist with Swann Auction Galleries in New York City, puts it:

“[Dealers] also absorb the risk of holding the material, not knowing whether they will be able to make a potential sale, and at what price. They also take on the responsibility of any repairs, cleaning and cataloging the item, insuring it, storing it, along with marketing it and ultimately vouching for its authenticity, provenance and condition to potential buyers.”

Some ROADSHOW appraisers who own their own companies, like Folk Art expert Allan Katz, private dealer and owner of Allan Katz Americana, often get their inventory from reputable dealers that they know or have worked with in the past. They also buy and sell items based on current market value, which can limit the high end of financial gain for the seller, since a private sale excludes the potential of a “bidding war” that auctions can create, sometimes resulting in a spiraling hammer price several times greater than a fair market retail value.

Katz told ROADSHOW that he attempts to sell items he purchases for prices that reflect current market valuations. “The price structure for most pieces can be quite subjective. It's why when valuing objects on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW we always give a range. Clearly, it's not a perfect science. Sometimes a new acquisition will sell in a day, yet some can take a year or more to sell, especially if it's very expensive.”

And even if a dealer has a potential buyer lined up, there’s no guarantee that the sale will go through, thus creating even more of a risk for the dealer, who has usually/often put down their own money to acquire the item from the original seller in advance. Oftentimes a dealer may “shop around” the item to prospective buyers.

“The risk for private sales is that if the few clients get wind that a piece is being 'shopped around,’ then they are less enthusiastic,” Dunbar told ROADSHOW. “Now the dealer may have to drop the price — almost like a ‘reverse auction’ — in order to lock in a buyer.”

So while selling an item through a private dealer may be the easy route, it is often a risky challenge for the dealer, involving a large amount of behind-the-scenes work. On the other hand, that’s what antiques and art dealers are in business to do, and they stand to make a tidy profit from their successful efforts.

Selling Publicly: Going to Auction

If a seller decides to go through an auction house to sell their item, they are essentially agreeing to accept a few non-negotiable factors from the outset that distinguish the process from working with a dealer. The first is a longer timeline. “An auction consignment agreement requires the seller to work with the auction schedule, which almost always means a wait (think months not weeks),” says Eastland. The second factor to understand is that an auction house makes money by collecting fees from both parties as pre-agreed percentages of the “hammer price” — the final amount of the winning bid.

Paintings & Drawings appraiser Betty Krulik, who is currently a private dealer, but has spent a portion of her career at Christie’s, describes an example: “Depending on the value of a work of art, the auction house will charge a commission of between 10% and 20% on the seller's side, while they also get an additional, say, 25% on the buyer's side” — the so-called “BP” or buyer’s premium.

So what’s the main benefit of going through an auction? “The advantage of the auction environment is that if you have a rare, desirable and fresh-to-the market item like the Walter Johnson-signed baseball,” Dunbar told us, “then it can sell for a multiple of what was originally expected.”

Asian Arts appraiser Lark E. Mason, who owns the auction house Lark Mason Associates, and has been involved in countless auctions and private sales alike over a more than 40-year career, points out that an auction is an ideal platform for a large group of buyers, who are all interested in a particular corner of the market, to come together and potentially stir up attention for a piece by trying to out-bid one another. "Auctions are an efficient means of transferring ownership of an object or group of objects, often that have some similarity....which are aggregated together to attract a wide audience of potential bidders who would share a similar interest." He notes that these auctions are free to the public and advertised to draw in as many interested parties as possible.

However, Dunbar goes on to note that “the risk is that if there aren’t enough interested buyers to create the competition needed to drive up price,” bidding can sometimes stall, and the item may get snapped up at a bargain, or even fail to sell at all.

In regard to the Walter Johnson-signed baseball that Dunbar appraised in Filoli, the guest chose to sell the ball through Leland’s auction house, which turned into a home run for the guest, as the ball sold for over $315,000.

As Dunbar noted, “I doubt a dealer would have had the nerve to ask more than $150,000 to $175,000, so auction was the best way to go here!”

Information for this article was contributed by ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraisers Leila Dunbar, Devon Eastland, Allan Katz, Betty Krulik, and Lark Mason Jr.