Comic books tell stories in a series of neat, contained panels—and yet the universe they create has such far-reaching impact as to give way to entirely new imagined worlds.

The following list includes just a few of the different artists inspired by comics, cartoons and caricature. The resulting works range from visual arts to film to celebrity costume design, and in each instance, something distinctly new emerges from cartoon beginnings.

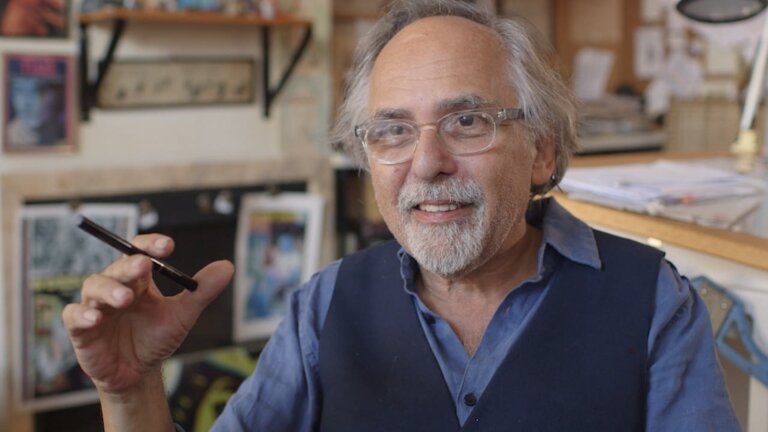

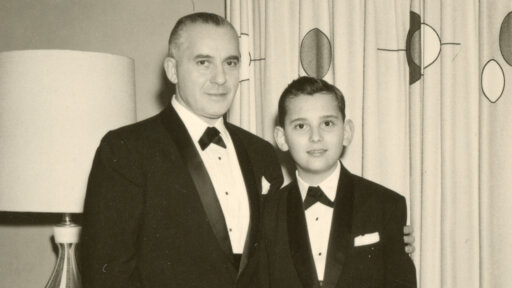

Art Spiegelman

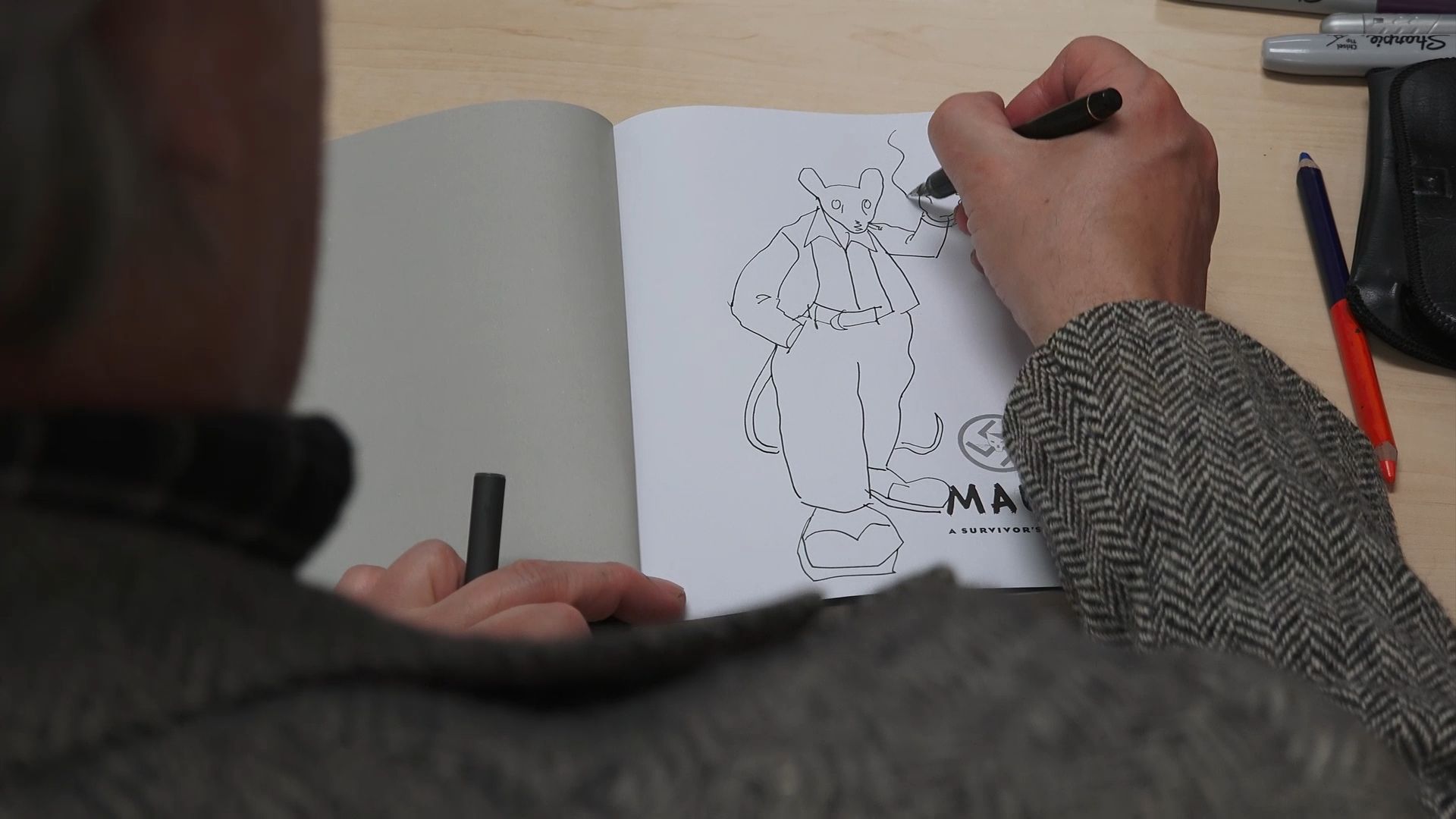

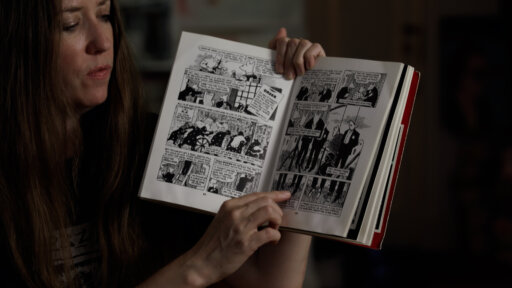

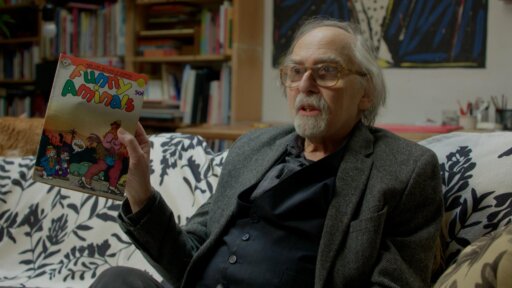

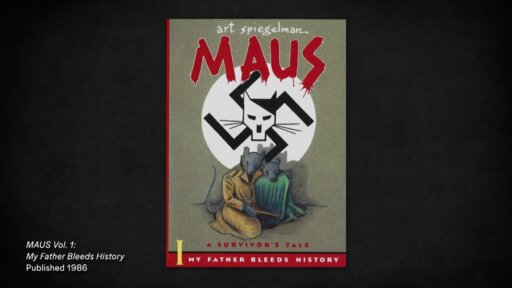

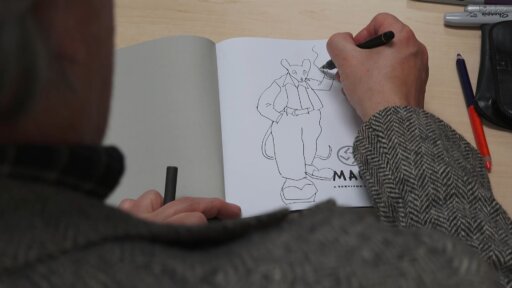

Art Spiegelman is best known for his graphic novel Maus, which tells the story of his immediate family and their experience as Jews in the Holocaust. Spiegelman based the novel on the oral history of his father, who lived to tell the tale; his mother, who also made it out alive, but later died by suicide; and his older brother, who didn’t survive. It’s a weighty history to tell in a comic strip, but Spiegelman resists the idea that there is anything trivial about the form: “Comics are more flexible than theater, deeper than cinema. It’s more efficient and intimate.”

In Maus, Spiegelman relies on the flexibility of the medium to sustain its defining animal metaphor. Jews are mice and Germans are cats; Poles are pigs and Americans are dogs. The power dynamics and blatant dehumanization is laid bare. The novel is popular on both high school syllabi and banned book lists—books prohibited or restricted by governments, schools, and other authorities because of their content. Many titles over the years with lasting cultural significance have landed on this list.

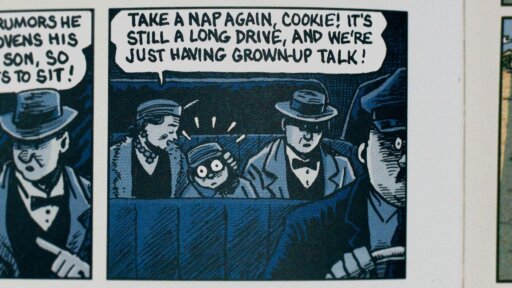

Maus—and Spiegelman’s broader body of work—all trace back to the comic books he grew up reading. As a child, he was obsessed with MAD magazine and the work of its founding editor, the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman. Spiegelman wrote a memoir about his childhood inspiration titled MAD Youth, in which he clearly credits the magazine as the origin of his life’s work. Perhaps the most striking throughline is a 1955 story from EC Comics, the consortium of comics MAD was originally housed under. The story, “Master Race,” asked an unusual question for a comic strip: What would happen if Holocaust survivors came face to face with their tormentors?

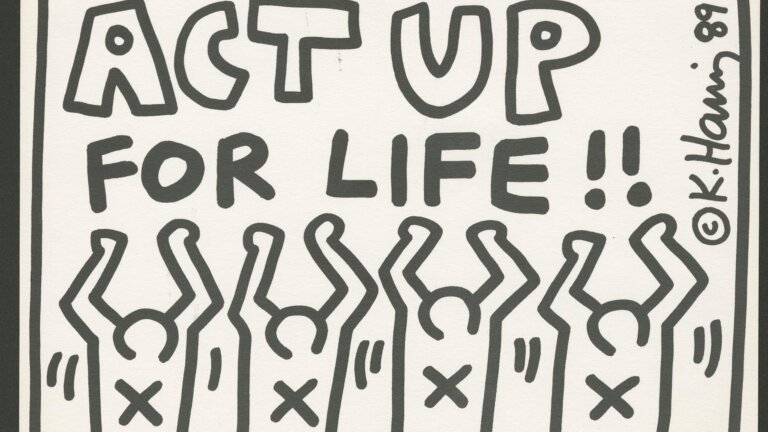

Keith Haring

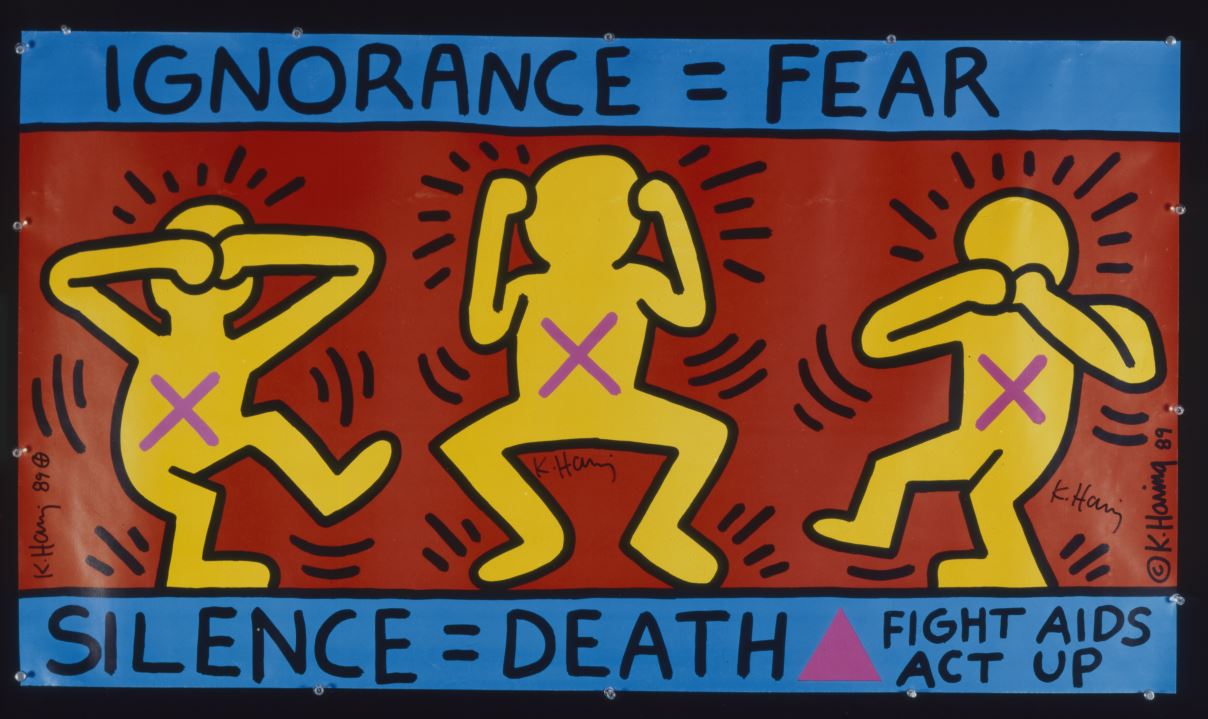

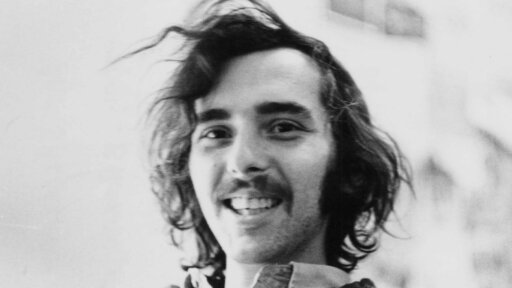

Keith Haring’s artwork is ubiquitous by design. Haring is a giant in the world of pop art, and his cartoony work has been widely commercialized: it graces T-shirts and gallery walls alike. Haring was insistent on democratizing his art, whether that meant subway graffiti and street murals or affordable posters and magnets at Pop Shop, the store he opened in the mid-80s in New York City.

Haring was first inspired by his father, an amateur cartoonist who introduced his son to Walt Disney and Dr. Seuss and encouraged him to pursue original works. That influence is evident throughout his career. Perhaps most obviously, much of his work included images of Mickey Mouse, and although he did not necessarily have Disney’s blessing in recreating their work, the studio reached out to him asking to collaborate in 1990. At that point, Haring was in the final weeks of his life; he died at 31 from AIDS-related complications.

Despite the childlike quality of Haring’s work, his art had a message from the very beginning. As a kid in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, he put up “Jesus saves” street art during a particularly religious phase of his youth. As he grew up, the causes to which he lent his talents evolved to anti-Reagan subway art, AIDS activism both before and after his own diagnosis, anti-apartheid messages and warnings on drug abuse.

Haring is often talked about in the same breath as Andy Warhol, who was another influence of Haring’s and a close friend—but as Haring’s biographer Brad Gooch notes, Warhol “took these kind of silly subjects and treated them seriously,” like his iconic rendering of cans of Campbell’s soup. Haring did the opposite.[i]

It is perhaps just that juxtaposition—of playfulness and urgency—that cemented Haring’s legacy long after his death.

Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson is known, above all, for a distinct and meticulously crafted aesthetic. He curates a pastel nostalgia that lays over his movies like a filter, and there is a tongue-in-cheek approach to rendering a full adult complexity in children in many of his works. Love is almost always unrequited, and the line between sadness and humor is often blurred: there is an endearing melancholy at the core of many of Anderson’s works. It’s the same tender melancholy for which Charlie Brown of “Peanuts” is known and loved.

Anderson is a longtime fan of Charles Schulz and the world of “Peanuts”; he’s alluded to the comic strip in several of his works. One in particular—“Moonrise Kingdom”—is rife with references. The protagonists are children with the same put-on adult seriousness of Charlie Brown. Suzy—one of the protagonists of “Moonrise Kingdom”—wears a pink dress reminiscent of Schulz’s character the Little Red-Haired Girl. The Boy Scout troop mirrors Snoopy’s Beagle Scouts. And just in case you miss the subtler references, there’s also a dog named Snoopy.

Several other movies tie back to “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” in which the plot centers on the construction of a play. Anderson employs the same Russian-doll narrative approach in “Rushmore,” “The French Dispatch” and “Asteroid City.” In “The Royal Tenenbaums,” a version of “Christmas Time is Here” from the “Peanuts” Christmas special plays in the background of many of the scenes where Margot, Gwyneth Paltrow’s character, comes onscreen. “The Royal Tenenbaums,” like “Moonrise Kingdom,” is another story line that centers on children and sidelines the adult characters—just as the adults of the “Peanuts” universe are relegated off-screen (or out-of-panel).

“I have always been interested in the characters and the world he created,” Anderson said of Schulz. “There was such a strong sensibility in those stories.” In Anderson’s films, that same sensibility serves as the scaffolding of his movie sets.

Elvis Presley

Elvis Presley’s childhood collection of Captain Marvel Jr. comic books still sits in the attic of his Graceland estate in Memphis. Presley grew up in poverty in Tennessee and worked to help his parents with the finances as a teenager. As his music career began to take off, his world shifted dramatically: not unlike the divide between working-class Freddie Freeman and his superhero alter-ego, Captain Marvel Jr.

As Presley’s career grew and his life was transformed by fame, he cultivated a celebrity persona that mimicked the Americana superhero. The iconic jumpsuits he wore onstage often included a cape and his TCB (Taking Care of Business) logo with a lightning bolt exactly like the one across Captain Marvel’s chest. He grew his dark hair and sideburns to match the look of Freddie Freeman.

Neither Presley nor his costume designer Bill Belew ever explicitly articulated the Captain Marvel inspiration, but Presley certainly leaned into the superhero narrative. In an award acceptance speech in 1971, he said: “When I was a child, ladies and gentlemen, I was a dreamer. I read comic books and I was the hero of the comic book. I saw movies and I was the hero of the movie. So every dream I ever dreamed has come true a hundred times.”

That line is also incorporated into the script of the biopic “Elvis,” in which Presley, played by Austin Butler, delivers it while wearing coveralls with a lightning bolt. In the movie, Presley is described as “transforming into a superhero” onstage.

The Elvis/Captain Marvel influence became a two-way street in the nineties, well after Presley’s death. In the 1996 limited series “Kingdom Come,” the artist Alex Ross remakes Freddie Freeman as King Marvel, with a high-collared, bell-bottomed suit. Mary Marvel is drawn to mirror Priscilla Presley. Just as Presley had imagined as a child, he was indeed the hero of the comic book.

Kara Walker

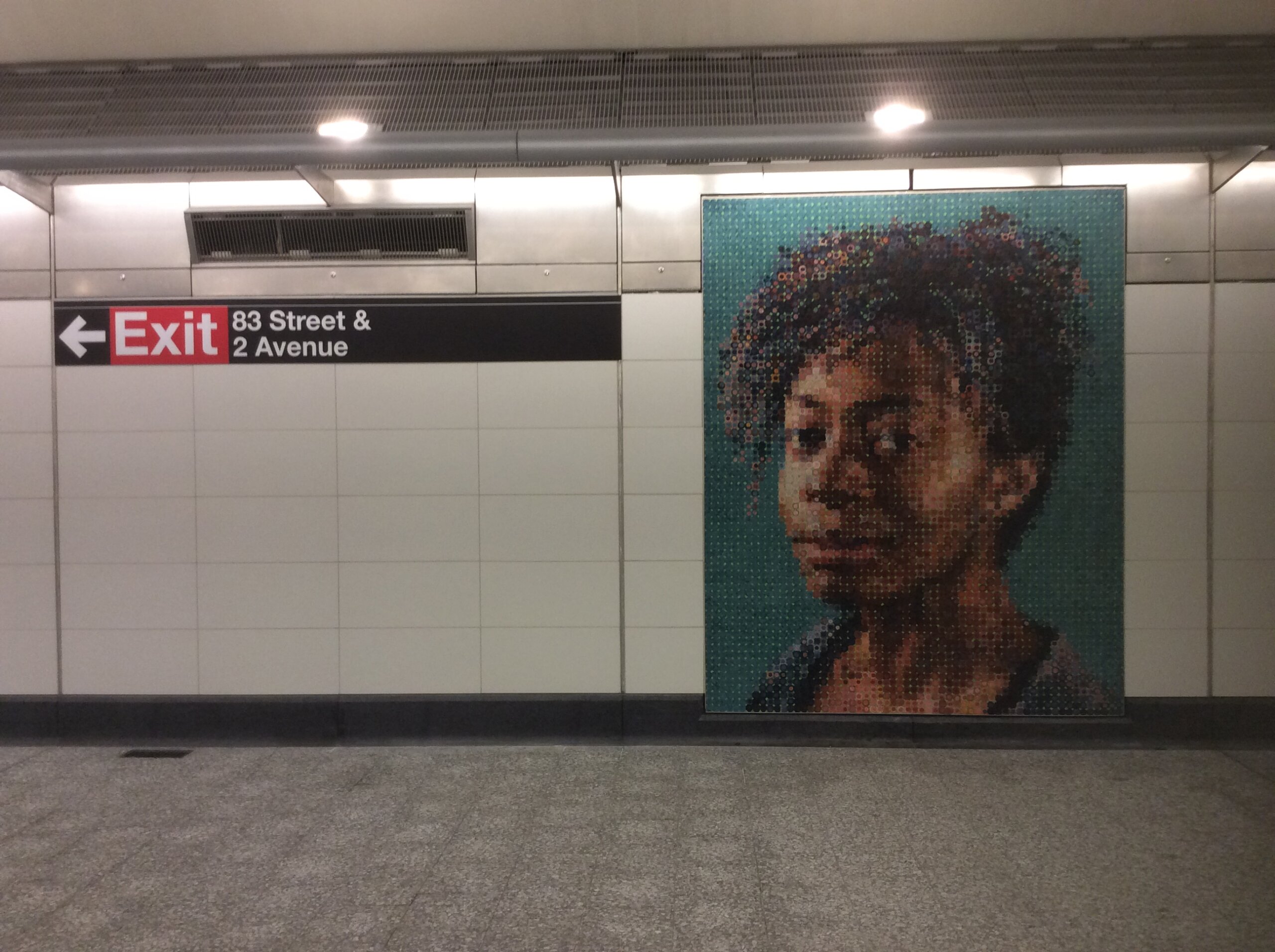

The new 86th Street station on the Second Avenue Line in January 2017. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons.

Kara Walker grew up wanting to be the next Charles Schulz. Instead, she’s creating a new and distorted American art history.

Walker is known for works that layer silhouetted figures—usually shadows of caricatured Black people—on top of Western art of the antebellum South. She remakes the scene in unexpected and often sexually explicit or grotesque ways; her work makes clear that slavery stripped humanity from Black and white people alike. Walker borrows from the existing art historical record and leans on caricature—which, particularly in a racial context, behaves as the sinister sibling of a cartoon—to underscore the sheer obscenity of America’s original sin.

One of her earlier works is a thirteen-by-fifty-foot mural titled “Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart.” A New York Times art critic described the work as “a surreal, raunchy, angry fantasia on the world of antebellum slavery,” that looks like “a cross between a children’s book and a sexually explicit cartoon.” Walker said it was her proudest moment, that early recognition of her unprecedented talent.

When Walker was 12, she went to an Andy Warhol exhibition with her father. For much of her adolescence, she idolized his bright style and his insistence on making art that bluntly reflects reality. But as she grew older, she recoiled at his use of the vast space his fame afforded him to make art from the material status-quo of the white and wealthy—and for doing so without critique. Walker, too, is in the business of bluntly reflecting reality, but she does so through distinctly unreal scenes that reveal uncomfortable truths of the American past and present.

***

Walker’s critique of Warhol can easily be extrapolated to the genre that inspired his work: comic books have long been an overwhelmingly white male space.

That’s slowly changing. Whether it’s “Black Panther”—and works inspired by the world of Wakanda, like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Roxane Gay’s spinoff series—or Katsuhiro Otomo’s manga series “Akira,” the comic book canon is expanding to include a greater diversity of artists and characters.

The butterfly effect of new imagined worlds is sure to reflect that change. And in the words of Art Spiegelman—who is widely credited for legitimizing comics as an art form—the medium is sturdy enough to support any story, for anyone.

“It never occurred to me that comics were anything other than worthy,” said Spiegelman. “They were in fact among the most worthy endeavors I could imagine […] I always assumed they were a container big enough to hold whatever I could hold.”

[i] 37 minutes LARB Radio Hour Podcast

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.