Finding Your Roots

Episode 9: Southern Roots

Season 4 Episode 9 | 52m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

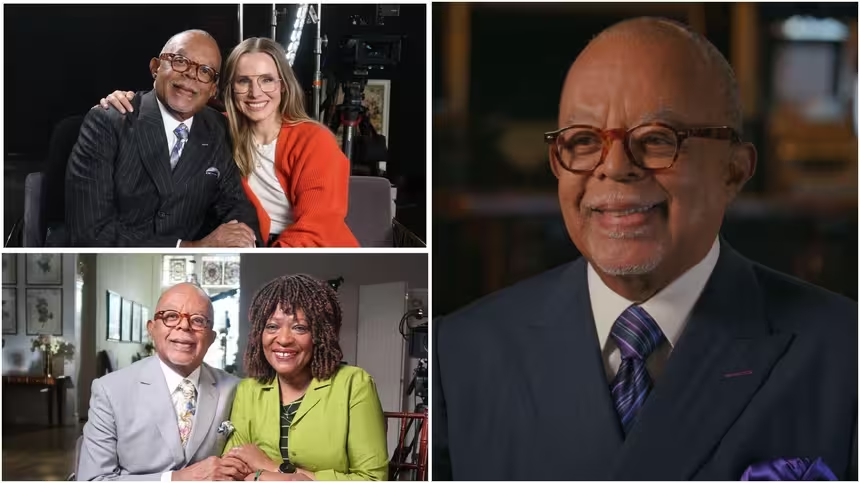

Questlove, Dr. Phil and Charlayne Hunter-Gault join Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Questlove, Dr. Phil and Charlayne Hunter-Gault. Three guests of disparate backgrounds dig into their Southern roots, where slavery and its aftermath shaped families both black and white.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Episode 9: Southern Roots

Season 4 Episode 9 | 52m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

Questlove, Dr. Phil and Charlayne Hunter-Gault. Three guests of disparate backgrounds dig into their Southern roots, where slavery and its aftermath shaped families both black and white.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHenry Louis Gates Jr: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots".

In this episode we'll meet talk show host Dr.

Phil McGraw.

Renowned musician Questlove and groundbreaking journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault.

Three people from very disparate backgrounds who's family trees were shaped by slavery.

Can you imagine working all day next to a man who owned you?

McGraw: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Or working all day next to a man you owned?

McGraw: Inconceivable.

Hunter-Gault: Somehow, I never thought about my own background that would've included slaves.

It's something I never heard anything about.

Thompson: We need to feel like we were somebody or, like we came from somewhere.

I never knew where I came from.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You wanna find out?

Thompson: Hell yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool genealogists helped stitch together the past from the documents their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts used the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

This is your book of life.

McGraw: Oh, wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We've compiled it all into a book of life... Hunter-Gault: Oh my goodness!

Thompson: This is mine?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's yours.

A record of our most compelling discoveries.

Thompson: Oh wow!

McGraw: I've watched TV miniseries that didn't have as many twists and turns as this.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My three guests have deep roots in Alabama, Texas, and Florida... Places where the long shadow of slavery fell across families both Black and White.

In this episode, the stories of their ancestors will transport them back into this shared past challenging their preconceptions and inspiring them to look at themselves in a new way.

[Theme music plays].

♪♪ ♪♪ Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ahmir Khalib Thompson, better known as Questlove, is renowned for his musical genius and his seemingly boundless energy.

He's a drummer, a DJ, a record producer, and a band leader.

He seems to work 24/7.

And music, plainly, is his life-blood... Thompson: My dad was a '50s doo-wop singer.

He had many labels back then, but probably the most notable was chess records.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mmm-hmm, famous.

Thompson: Yeah, they had, like, three local hits in the world of doo-wop, and then in the '70s he kind of built a show around my family, my mother Jaquie, and my Aunt Karen, and built a really good nightclub act.

You know, they would perform at the Poconos, Catskills, Atlantic City... Henry Louis Gates Jr: The circuit.

Thompson: Yeah, it was, like, five shows a night.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: God, that's a lot of work, man.

Thompson: It was typical.

Like, you know, first set at 7 o'clock, last set at 1 in the morning.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Questlove was raised in the family business quite literally.

He grew up surrounded by musical instruments spent his time listening to records while other kids were out playing sports and when his parents went on tour, they took him along... Thompson: I was nine years old running lights, like helping my dad cut light gels, doing electronic stuff.

They really weren't sweating it back in the '70s and '80s, like it was nothing for a nine-year-old kid to get a ladder and start, you know, placing lights on the stage... Henry Louis Gates Jr: It wasn't long before Ahmir was performing on his own.

In high school, he launched "The Roots" with his classmate and close friend, Tariq Trotter.

But the band, which would win three Grammys and see one of their albums go platinum, wasn't created solely for the love of music... Is it really true that you formed The Roots to impress a girl?

Thompson: Yeah, yeah, I did.

She was in line ahead of me and she was talking about Prince, which instantly got my attention like someone else knows about Prince, so I was trying to figure out like how to double-dutch insert my way into the conversation.

And then, I caught myself lying.

I was like, "Yeah, I got a group, you know?

Me and um, me and Tariq are a group."

Yeah, and so then I ran to him and like, "If anyone asks you, we're a group, ok?"

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, did you get the girl, or not?

Thompson: I didn't get the girl.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Aw.

Thompson: But I got the career.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My second guest needs no introduction Dr.

Phil McGraw has been America's best-known therapist for almost two decades.

Offering his unique mix of tough love and practical advice.

McGraw: So, if you come in and alienate everybody and you're pissed off and you push everybody away and you're like a porcupine then you don't ever feel the sting of rejection.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Questlove, Phil is following in his father's footsteps but his path to success was by no means direct.

His childhood was deeply chaotic... McGraw: We bounced around every little town in Texas and Oklahoma, moved like tumbleweeds we lived in Yukon, Edmond, Oklahoma City, Tulsa.

We just moved all the time.

I was, I was forever the new kid in school.

There would be these kids that had grown up together and knew each other and I grew up forever the outsider.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Phil's tumultuous upbringing was driven by his father, Joe McGraw, who switched jobs frequently as he sought a fulfilling career.

And struggled with a drinking problem.

McGraw: My father was a bad alcoholic.

It's kind of like they ask you, "How are things going?"

you say, "Great, subject to immediate collapse."

That's, that's kind of the way it was.

You know, you just never knew, was the rent gonna be paid?

Were the lights gonna be on when you got home?

It really got to the point that the family was going to fall completely apart.

And so, he did have the presence of mind to say, "You know, enough's enough," and he walked away from it and said, "You know, I'm gonna go back to school.

I'm gonna go back and get an education".

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Joe's decision reshaped the McGraw family.

He gave up drinking earned a degree in psychology and eventually opened up his own practice... Phil would join that practice himself using it as the springboard for his remarkable career... But Phil has never forgotten the hardships of his youth.

They are palpable to him, even now and he credits those hard times for the man he is today.

McGraw: I still feel a connection to this boy right here.

When I look at him, that's me, and that child is still in me.

I remember how he felt at that time, what he was proud of, what he was ashamed of, what he was worried about, what was going on, and that all is part of who I have become, and I truly believe that what I'm doing now in my life is a culmination of everything I have done.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My third guest is Charlayne Hunter-Gault, one of our nation's premier journalists... The winner of two Emmys... A lifetime achievement award from the Washington Press Club and a Peabody.

But long before Charlayne was winning awards, she was making history.

(Crowd chanting) Henry Louis Gates Jr: In 1961, when she was just 18 Charlayne was one of two African Americans to integrate the University of Georgia.

A key event in the Civil Rights Movement... What in the world was that like, were you afraid?

Hunter-Gault: No.

We got put into us a pride that I think must have accounted for our calm attitude in the face of all of this resistance, because we knew about Black men and women who had survived so much.

And so as ugly as the crowds were, and as awful as the words they were yelling, it somehow didn't affect us.

Did not affect us.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charlayne's ordeal did not end with her arrival on campus.

Days later, a mob showered her dorm with bottles and bricks.

State troopers were called in and the school suspended Charlayne, supposedly for own safety, she had to fight to return.

Nevertheless, Charlayne persevered... And through it all, she was sustained by lessons she learned from her family, lessons that she says have guided her ever since... Hunter-Gault: There were Bible verses that my grandmother taught me.

I didn't want to learn them.

She'd go to church every day at 12 o'clock, and I'd climb a mango tree so she wouldn't find me.

But eventually she'd find me and make me learn Bible verses, and one of them served me, what was that, 14 years later, and it was her favorite psalm.

"Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil."

And while my grandmother was teaching me biblical things, my father passed along to me: "Study words, and one day you will walk with kings and queens."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Really?

Oh, that's beautiful.

Hunter-Gault: And who knew that when my father would say to me, "Study words, and one day you'll walk with kings, study words and one day you will use words for your life work."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's true, yeah.

Hunter-Gault: Yeah, they were prescient in a way.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Each of my guests tonight sees their success as the fruit of their immediate family.

Each learned values and skills in their childhood home that shaped their lives, and their careers.

Now I wanted to see what we could find by delving into their roots, to understand how they've been influenced by the achievements and sacrifices of ancestors they never even knew they had.

I started with Questlove, who was especially eager to take this journey.

Like many African Americans, he told me that he had long agonized over the thought that he would never know very much about his family tree.

Thompson: I'm beyond excited for this.

I've been waiting for this all my life.

To literally have roots like, what tree do you know can really thrive without any, any place in the ground?

Like, it's weeds.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: But we're gonna find out.

Thompson: Is there, like, music under this?

As you say this... "We're gonna find out, right after this," (Makes suspenseful music sound) Henry Louis Gates Jr: Our search began in Philadelphia, where Questlove was born and raised.

But he quickly moved south... His maternal grandfather, a man named Robert Lewis, was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1904.

And using Alabama census records, we were able to go back three more generations on this side of his family tree... Now, this is a page of the 1900 federal census right here, for Mobile, Alabama.

Thompson: "Joseph Lewis, head of household, age: 30.

Eugena Lewis, wife, 27."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Have you ever heard those names, Joseph and Eugenia?

Thompson: No.

I never knew where I came from.

I don't think anyone really had a clue.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Joseph and Eugenia are Questlove's great-great-grandparents.

It appears that they lived their entire lives in Mobile, much of that time under Jim Crow segregation... Records show that Joseph was a day laborer who worked at a lumber mill and Questlove couldn't help but reflect on the immense gap between his ancestor's fortunes and his own... Thompson: I'm wondering if Joseph Lewis imagined me.

Like, imagined that maybe there's a time where, you know, a descendant of his could, could thrive or.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And be successful, and make it in main.

Thompson: Be alive.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And make it in mainstream America.

Thompson: I'm thinking this period, just to navigate and survive, to make it from childhood to teen, to teen to adulthood.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A full-time job.

Thompson: And raise, it's a challenge, and, oh, man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Joseph Lewis was born around 1870, which means that his parents were almost certainly newly freed slaves.

As we tried to learn about their lives before emancipation, we faced a significant obstacle.

Enslaved people were not listed by name in most public documents, so it can be extremely difficult to find them in the historical record.

But in Questlove's case, we got lucky.

We were able to identify Joseph Lewis's parents, and this led to an almost unbelievable discovery... This is a page of the 1880 federal census, Ahmir, for Mobile, Alabama.

Would you please read the transcribed part of the census?

Thompson: "Charles Lewis, age: 60.

Maggie Lewis, age: 50.

Joseph Lewis, age: 11."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ahmir, you just.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You just met your third-great-grandparents, your great-great-great- grandparents.

These are your people, this is your blood.

Thompson: In Alabama.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mobile, Alabama.

And we're back 200 years.

Thompson: Oh, wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please turn the page?

Thompson: This is the best book I ever read in my life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please read where your ancestors were born?

Thompson: Oh my God.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You hit the jackpot.

Thompson: Oh, man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: According to the census, Questlove's third great-grandparents were both born in Africa.

This was an extraordinary find!

Very few African Americans are ever able to trace their ancestors back to Africa by name.

Thompson: "Charles Lewis, age: 60, place of birth: Africa.

Maggie Lewis, age: 50, place of birth: Africa."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: How do you feel?

Thompson: I, like, I'm not over-acting.

I'm not, uh, yeah, I'm at a loss for words.

I'm just so overwhelmed right now, because I never, I mean, until an hour ago, I didn't know who I was.

I said I wasn't gonna cry, man.

Oh, I didn't know who I was or who I came from.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Much like Questlove, Dr.

Phil has extensive roots in the South.

His family has lived in Texas for five generations.

But even though Phil spent a great deal of his life in the Lone Star State, he knows surprisingly little about his ancestors who preceded him there... McGraw: I probably know less about my history than most people, I can assure you.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your parents didn't talk about great-great-grandmamma, so-and-so, great-granddaddy?

Very much about the here and now.

McGraw: There was a lot of friction between my parents and their parents.

Uh, there was not a closeness between that generation.

There was a connection, but it wasn't always smooth water.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Our search began in the archives of Collin County once part of a farming region in Northern Texas.

Now on the outskirts of the sprawling city of Dallas... Here, we found a marriage record for Phil's paternal grandparents, and, already, I was revealing new information to him.

It's dated April 17, 1909.

Would you please read the transcribed section at the bottom?

McGraw: "You are hereby authorized to solemnize the rite of matrimony between Mr.

Joe McGraw and Ms.

Susan Edda Strickland.

Now, see, you're getting into some unplowed ground for me, because I never knew her name was Strickland.

I never knew her first name was Susan.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No kidding.

Well, look at that next page.

That's the marriage record for your grandfather Joseph's parents, John McGraw and Mary Rice.

McGraw: Never heard them ever till this very moment.

And this is in Collin County?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Same county.

McGraw: I've been to Collin County hundreds of times; I had absolutely no idea that my grandparents had been there or my great-grandparents.

I never even heard my great-grandparents' names.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: As it turns out, Phil's roots around Collin County are deeper than he ever imagined... His third great-grandfather, a man named Jonathan Newby brought his family into nearby Navarro County in the mid-1840s, just a few years after the Battle of the Alamo!

It was a perilous time in the state's history... Texas was very much part of the American frontier, and just across its border, war with Mexico was brewing... Phil's ancestors were taking a considerable risk... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, Phil, you're looking at a tax record from the Texas archives.

This is dated 1846.

Could you read the transcribed section?

McGraw: "Assessment of property lying within Navarro County, owned by residents thereof: Jonathan Newby."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Phil, this is the very first record for your father's ancestors in the state of Texas.

McGraw: Man.

He did not move into a tranquil area.

I mean, this was... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Let's find the most dangerous and see if we can be killed.

McGraw: What the hell were they thinking?

What's wrong with you people?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Despite the dangers, Phil's family prospered in Texas.

By 1850, Jonathan Newby owned a 430-acre farm where he grew corn and oats.

He also owned horses, oxen, and over 50 pigs... But that's not all the property that Jonathan owned... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please turn the page?

That's part of the 1850 census, and it is the slave schedule for Navarro County, Texas, and you see any familiar names?

McGraw: Well, Jonathan Newby.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Can you see how many slaves Jonathan owned?

McGraw: He had one, two, three, four, five, six slaves.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: One male, age 28, one female, age 20, two young females, ages 13 and three, and two young males, ages two and three months.

McGraw: So it looks like a family.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It does indeed.

McGraw: I'll be damned, I'm shocked.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He would have close, daily contact with these people.

They worked side-by-side in the fields together.

Now, can you imagine that, working all day next to a man who owned you?

McGraw: No, no.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Or working all day next to a man you owned?

McGraw: No, inconceivable, inconceivable.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Phil, of course, is not alone.

Many of my white guests with Southern roots have slave-owners in their family trees.

Occasionally, some of my Black guests do, too.

It can be disturbing to see the evidence on the page, but it's much more common than we would think.

However, as we tried to learn more about Phil's ancestor, we uncovered something that I have rarely seen before... McGraw: "Newby, Jonathan... Killed by a slave on farm, one mile Hackberry Creek."

So a slave killed him in the fall of 1853?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like to see this, Phil?

McGraw: Well, they weren't a boring bunch, right?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you think was going on between them?

McGraw: What goes through my head as I'm looking back here at the descriptions, and I'm seeing some, uh, young females here, two young females age thirteen, and one female age twenty, so it kind of makes me wonder if maybe he was taking revenge for something that had happened to his family.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We don't know why Phil's ancestor was killed, or if the enslaved man accused of murder was actually guilty there are simply no records to guide us.

But we do know what happened next.

When Jonathan Newby died, one of his sons, John Henry Newby, ended up taking the law into his own hands... McGraw: "A large number of the neighbors met at the Newbys' house and decided that they would hang the Negro, but after considering this for some time they concluded that his punishment should be inflicted by John Newby.

They decided that John Newby should shoot him."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your great great-granduncle, shot the slave believed to have murdered his father... McGraw: No trial.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Nnn-nnn.

McGraw: They ever find out if he was the right guy?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No.

McGraw: Well, frontier justice, right?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That was frontier justice.

McGraw: Which is no justice at all.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, what do you think happened to John Henry.

McGraw: Probably not a damn thing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Phil, I was confident that John Henry would go unpunished.

But we were both wrong... Slaves were valuable property, and the Texas state constitution had made it illegal to kill them.

So John Henry was arrested, and sentenced to three years in prison.

But the story doesn't end there.

Soon after the sentence was passed, Sam Houston, the governor of Texas, intervened... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, this is a letter written almost immediately after John Henry's trial, and it's signed by Sam Houston himself.

McGraw: "At the spring term A.D.

1860, I do hereby grant to the said John Newby a free and full pardon for the killing of the said Negro man Jo."

So, Sam Houston pardoned him.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Sam Houston pardoned him.

The governor of Texas pardoned him.

McGraw: Okay... Henry Louis Gates Jr: You can't make this up, Phil!

McGraw: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like for you to learn this, Phil?

McGraw: Well, you know, it's really surprising, and I, you know, you realize what the mores and folkways of the times were.

But what you hope is that maybe, maybe somewhere, somehow, some way, um, it caused somebody to start re-thinking, how these human beings were being treated and valued.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Much like Phil and Questlove, Charlayne Hunter-Gault knows very little about her distant ancestry.

We began on her mother's side, hoping to take her back into the slave era.

But along the way, we uncovered a story that shows how vulnerable African Americans were, even after they had been freed.

It started with Charlayne's grandmother, Frances Wilson, who taught Charlayne Bible verses when she was a child.

Charlayne told me that she was especially eager to learn about Frances' family we found Frances' mother, a woman named Ellen Wilson, in the 1880 census, living with her parents.

Hunter-Gault: Oh my, this is, this is really close to my heart.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, I want you to notice something.

Would you read what it says in the health column by Ellen's name on the right?

Hunter-Gault: Hmm, "Is the person sick or temporarily disabled, lying in?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ellen is listed as lying in, that was a code for she'd just had a baby.

Hunter-Gault: Okay.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Can you find Frances?

Hunter-Gault: Yeah, right here.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A one-day-old child.

Isn't that amazing?

Hunter-Gault: That's beyond amazing, my grandmother.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes.

Hunter-Gault: At one day old.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: At one day old.

The census-taker beats on the door, they go, "Anybody living here?"

They go, "Yeah, my daughter's lying in," she was 16, and she just had a baby.

Hunter-Gault: I didn't realize she was that young.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Hunter-Gault: So, she, oh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: She was 16.

Hunter-Gault: Ooh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ellen did indeed give birth to Frances at a young age and what's more: she was unmarried and living with her parents at the time.

Which raised the question: who was Frances' father?

Charlayne told me that growing up, she had heard rumors that Ellen had become pregnant while working in the home of a White family... Hunter-Gault: Somehow I heard the story my grandmother's mother, had been impregnated by the master's son, and they threw her out of the house.

And I don't know whether it was rape or whether it was consensual.

I never knew, but I don't think those who told me the story knew.

Because I've always guessed, but I've never had any way of knowing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Stories like this are distressingly common in African American families, and just as distressingly difficult to prove.

But we had a clue to guide us according to Charlayne, her great-grandmother Ellen Wilson had worked for a White family named "Harris".

So we started searching Georgia's archives, trying to find a White Harris family that was in any way connected to Charlayne's Black Wilson family.

It was slow going at first there were simply too many Harris families to sort out.

So we turned to DNA and when we compared Charlayne's results to the DNA of people in multiple databases, we discovered that she has close relationships to several White people with the surname "Harris."

But one match in particular stood out... In a moment, I'm gonna show you a chart of your DNA compared to the DNA of the closest match we found for you who has a Harris ancestor, a White person.

You'll see red bars to illustrate any DNA that you share with this person.

Would you please turn the page?

Hunter-Gault: Ooh, it's red as measles on this page.

Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is a significant amount of red.

We got a very strong match to an individual whose roots stretch back to a White Harris family that lived roughly 25 miles from where your grandmother was born.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now that Charlayne's DNA had tied her to a specific Harris family, we focused our research on that family... And in 1870 census for Morgan County, Georgia, we found a farmer named Samuel Harris... The census lists the members of his household.

At the bottom was a familiar name... Hunter-Gault: "Ellen, age: 6."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We believe that's Ellen, that is your great-grandmother living in the house of Samuel Harris when she was six years old.

Hunter-Gault: Oh, my God.

Oh my... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Just like your family story said.

She was raised in the family.

Hunter-Gault: Mmm-hmm, until.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: She gets pregnant.

Hunter-Gault: Ooh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And there's something else about this record that I want to show you.

Can you tell me how many sons live with Samuel in 1870?

Hunter-Gault: Yeah, there's, uh, is Ridding is 19.

Richard is 14, and William is nine.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, we believe that one of these three boys fathered your grandmother Frances.

Hunter-Gault: Looking at this just sort of makes me angry.

That they took advantage of this child who clearly had grown up in their house.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh yeah.

Hunter-Gault: So, you get it, you know, this just brings out a range of emotions of all kinds.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Complicated.

Hunter-Gault: Yeah, it's complicated.

These stories need to be told.

It's important to know this history.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had already taken Questlove back to his third great grandparents, Charles and Maggie Lewis, who were born in Africa.

Now, as we dug deeper into their lives, we noticed something strange.

Charles was born around 1820, Maggie around 1830.

And those dates stood out because the trans-Atlantic slave trade was outlawed in 1808.

After that, very few Africans came into the United States.

Meaning that Charles and Maggie must have been smuggled into this country illegally!

We'd never seen this before in the series.

And it led us to a stunning story.

Now, Ahmir, this is an article that's published in the newspaper called the "Tarborough Southerner" on July 14, 1860.

Thompson: "Arrival of a cargo of African Negroes... Schooner Clotilda with Africans arrived in Mobile Bay today.

A steamboat immediately took them up the river."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: On Monday, July 9, 1860, a ship called the Clotilda arrived in Mobile Bay carrying 110 African slaves.

It's the last known slave ship to come to America.

Your family settled less than two miles from an area, Ahmir, you ready for this, known as Africatown, which was founded by survivors of the Clotilda.

Thompson: I'm frozen, man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You know, every African-American that we know wants to know where in Africa they came from and then how they came here.

You are the only African-American I've ever met who can name the ship!

Thompson: I'm on the absolute last ship that ever came here.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The story of the Clotilda begins with a man named Timothy Meaher, a plantation owner and steamboat captain in Mobile, Alabama.

According to newspaper accounts, in 1858, Meaher made a wager, betting that, in spite of the law, he could bring a shipload of Africans into the United States.

The Clotilda was used to win that bet.

In 1860 it sailed to the Kingdom of Dahomey, now part of the Republic of Benin, purchased roughly 125 human beings, then sailed back to Mobile, with Questlove's ancestors on board.

This was published in the Pittsburgh Daily Post on April 15, 1894.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

Thompson: Of course "Captain Timothy Meaher was a defender of 'the institution, and declared that despite the stringent measures taken by most of the civilized powers to crush out the oversea traffic, it could still be carried on successfully, offered to wager that he would 'import a cargo in less than two years."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That man made a bet with another man that reshaped your entire family tree.

A bet.

Thompson: Oh my God.

I can't stop looking at this person.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Questlove wanted to know more about what his ancestors endured.

We showed him the journal of the captain of the Clotilda, a man named William Foster.

It describes in detail how he obtained his cargo... Thompson: "From thence I went to see the King of Dahomey.

We went to the warehouse where they had in confinement 4,000 captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select 125 as mine."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The odds, think about the odds, man.

Thompson: So, 4,000 chosen.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: There were 4,000 captives, all enslaved.

So, the Kingdom of Dahomey was famous for selling slaves, and they sold slaves to Europeans.

White man shows up, he's trying to satisfy this bet, make some money, and he picks 125 people.

Just by random accident, one of them is your ancestor.

What's it like to learn all this, to be able to name and see on a map the very place in Africa that your family comes from, to know the circumstances.

Thompson: I mean, all types of emotions are running through my head.

Uh, I feel sad, I feel angered, I feel confused, I feel lucky.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Questlove now knew more about how his African ancestors came to the United States than anyone I've ever met.

But there was still another beat to their story.

Captain Foster's journal indicated that when the Clotilda arrived in Mobile, the captive Africans were transferred to a steamboat, taken to a hiding place on an island in the Spanish River, and then sold.

We don't know who purchased Questlove's ancestors, but we do know that after they were freed, Charles and Maggie Lewis became farmers, living close to the river where they likely came ashore in America.

Many of their descendants still live in that area today, and thanks to them, I had one last thing to reveal... Could you please turn the page?

You, Ahmir, are looking at your third-great-grandfather.

That is your original African ancestor, brother.

That is Charlie Lewis.

Thompson: How, how, how, how did you?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The photo comes from a descendant of Charlie Lewis like you, one of your cousins.

Thompson: That's my great-great-great-grandfather.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is your third-great-grandfather.

Thompson: The eyes are the same.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You know how lucky you are, Ahmir?

It's a miracle.

Thompson: I've never imagined this in my entire life, that I'd see this.

I just have to keep looking at him, 'Cause those are my eyes, man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, now you know where they came from.

Thompson: This is coming full circle.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had already taken Dr.

Phil's paternal roots back to the Texas frontier of the 1840s.

And we had much further to go.

We were able to trace this line of his family across the eastern United States and identify Phil's sixth great-grandfather: a man named Henry Newby.

We believe that Henry was born in England sometime around 1680.

Though we couldn't find the documentation to prove it.

What we did find is evidence that by the early 1700s, Henry was living in Lancaster County, Virginia... McGraw: This is all the way back to the Colonies.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: All the way back to the Colonies.

How many Americans can trace back to their sixth great-grandfather?

McGraw: Well I certainly didn't think I would.

I seriously did not think I would.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: This guy is born 100 years before the end of the American Revolution.

McGraw: Yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And he's your ancestor.

McGraw: You know to actually find these folks by name?

And where they lived and when?

That's really fascinating.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Henry Newby was a direct ancestor of Jonathan Newby, the Texas slave owner.

The two men are separated by just three generations on Phil's family tree.

But Henry's experience in America was radically different from Jonathan's... This is an appraisal of the estate of a landowner named George Heale.

And it's from the Virginia colony, dated 1702, and at that time, Henry would have been roughly 22 years old.

George Heale had died, and his property was being appraised can you read it, that list down there?

McGraw: "Servants and slaves.

Henry Newby, two pounds sterling, ten pence."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your sixth-great-grandfather, Henry Newby, was an indentured servant.

McGraw: Wow.

McGraw: It's amazing isn't it?

So, he was either working off some type of maybe passage, or some type of penalty.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

McGraw: I mean, I've watched TV miniseries that didn't have as many twists and turns as this.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Indentured servants were crucial to the economy of colonial Virginia... They generally worked on plantations, alongside African slaves, under fixed-term labor contracts.

As Phil understood, many were exchanging years of work for passage to America.

Others were convicts.

Some were orphans.

They lived in bondage, often under harsh conditions.

So harsh, in fact, that four out of every ten indentured servants died before their contracts were fulfilled.

We wondered how Henry Newby fared.

The answer lay in a court order issued in Lancaster County, Virginia... This is fascinating.

I'd never seen this before.

It's dated August 8, 1704.

McGraw: See, he's indentured in 1702.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's right, and this is.

McGraw: And here, two years later, "Ordered that Mrs.

Ellen Heale do pay unto Henry Newby his freedom clothes."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: His freedom clothes.

McGraw: He's out.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You ever hear that term, freedom clothes?

McGraw: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The contracts of indentured servants often called for a master to provide their servant with a set of clothes at the end of their labor.

It was both a symbolic and practical matter, as clothing was valuable in colonial Virginia.

And clearly: Henry had earned his.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: This is the moment of freedom for your ancestor.

What's it like to see this, Phil?

McGraw: Well, I got some roots.

I got some people.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You got roots and people big-time.

McGraw: Don't feel so shiftless.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, that's right.

You didn't know about any of these stories?

McGraw: None, not one.

It fills in a big void for me, I mean all of my life, I've had no information.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had already taken Charlayne's mother's roots back to Jim Crow Georgia.

Turning to the paternal side of her family tree, we set out to see if we could trace any of her father's ancestors back to slavery.

We began with Charlayne's grandfather, a man named Charles Hunter.

Charles was a preacher, from Florida, and Charlayne recalls him vividly... Hunter-Gault: When I was there, my grandfather was in the pulpit, and we, I had to go to church every Sunday.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Of course.

Hunter-Gault: Through, a few times during that day, and he was just preaching on and on and on.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He would, uh, get wound up and crouching low, he'd run from one side of the... Hunter-Gault: "Got two wings, to fly across Jordan, and the world can do it," see, I remember all that from 'cause he was powerful.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charlayne's grandfather may have been a memorable part of her youth, but she knew next to nothing about his family.

And, at first, he proved to be a challenge for our researchers.

We could not even find a birth certificate for him, or any records from his childhood.

Fortunately, we were able to locate his death certificate, and that contained a crucial clue to his roots... Hunter-Gault: "Father's name: Isaac Hunter.

Mother's maiden name: Filisher Alexander."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, Isaac Hunter and Felicier or Felicia Alexander are your great-grandparents.

Now, you've heard of Felicia, right, your ancestor?

Hunter-Gault: Nnn-nnn.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No?

Hunter-Gault: Never.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Have you ever heard of Isaac Hunter?

Hunter-Gault: Nope.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, great, well... Hunter-Gault: Ooh, surprise coming.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charlayne was right.

We did have a surprise for her.

Our researchers discovered an index of marriage licenses from the year 1866 in Jefferson County, Florida.

It contains a record of the wedding of Charlayne's great-grandmother, Felicia, but it doesn't show Felicier marrying Isaac Hunter.

Instead, she was marrying another man.

A man named Robert Alexander.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You ever hear of him?

Hunter-Gault: Nnn-nnn.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Robert Alexander isn't a blood relative of yours, but he and your great-grandmother had several children together.

Then, sometime between 1870 and 1880, he disappeared from the picture.

Not long afterwards, Felicia conceived your grandfather with Isaac Hunter.

Hunter-Gault: Oh, wow, oops.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: How about that?

Hunter-Gault: How 'bout that?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So Isaac Hunter was her second husband, or... Henry Louis Gates Jr: As it were, partner, the second father of her children.

You never heard anything about that?

Hunter-Gault: Never.

They never talked about that.

My grandfather, he preached hard, but he didn't talk much.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charlayne's great-grandmother Felicia was married in 1866, about a year after the end of the Civil War, which means that she was almost certainly born into slavery, probably sometime in the 1840s.

Normally, this would mean the end of our research, as we can rarely learn more about an enslaved ancestor than their name... If we can learn that.

But Felicia's wedding record contained a telling detail... Hunter-Gault: "I legally united in matrimony the persons whose names follow on the 8 December 1866 on the plantation of TJ Eppes."

What was that?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your great-grandmother was married on the plantation of a man named TJ Eppes.

His full name was Thomas Jefferson Eppes.

Now, this is 1866.

They were on the plantation.

Slavery only ended December 1865.

If your ancestor's getting married a year later on a plantation, you have to wonder, was your great-grandmother one of TJ Eppes's slaves?

This question sent our researchers into the records of the Eppes family... We learned that TJ Eppes was an attorney, and we found no evidence that he owned slaves.

But as we looked into his family background, we noticed something interesting in the 1860 census regarding TJ's father, a man named Francis Eppes... Would you please turn the page?

Hunter-Gault: This is getting really deep.

"Name of slave-owner, Francis Eppes."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You're looking at what's called a slave schedule and as you can see... Francis Eppes was a slave owner.

He owned over 107 human beings.

Hunter-Gault: Oh, that's so sick.

107 human beings, he owned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, we know that your great-grandmother Felicia would've been between ten and fourteen years old in 1860.

Francis Eppes owned five female slaves between the ages of ten and fourteen in 1860.

Hunter-Gault: Oh my goodness.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: One of them we believe was your ancestor, and listed as property in that slave schedule.

Hunter-Gault: And I so remember being thirteen, oh, how far away from that.

That's amazing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like, though, to look at that and think one of those girls is your nameless great-grandmother Felicia?

Hunter-Gault: It's pissing me off a little bit, and yet, on the other hand, that's, that's our story, part of our story.

I mean, here they were, voiceless.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Voiceless and nameless.

Hunter-Gault: Nameless.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Is it satisfying at all to know where this one ancestor was enslaved?

Hunter-Gault: Absolutely, because you can't, I mean, I talked about it with passion, but it's passion based on, on research.

It's not passion based on blood you know?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And it's only now that we can work our way backwards and figure out that she's got to be one of those girls.

Hunter-Gault: I hope I have a lot longer to live because I know this is going to inflame or fuel my passion.

Beautiful.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The paper trail had now run out for all three of my guests.

It was time to give them their full family trees.

Each watched their roots stretch back centuries, encompassing stories of slavery... servitude and freedom.

Seeing how their ancestors had endured this complex history compelled my guests to rethink their family stories and their own identities.

McGraw: Means a lot to know.

It's coming late in my life, so I'm glad that I got to know it while I could still know it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's great.

McGraw: 'Cause my mom and dad, they never got to know this.

Hunter-Gault: All of it has been a part of creating the armor that has enabled me to walk through mobs, that has enabled me to cover wars, uh that has enabled me to confront criminals.

To know your life history going back this far I think is very empowering in a sense.

It's beautiful to know, because when you don't know, you may be wearing that armor, but you really need to know, or would like to know where it came from.

Thompson: You know, before today, I was... I was a career-obsessed individual that would leave no stone unturned, to pursue the next achievement.

Which maybe I feel is, like, it's important for me to be in the history books because I know nothing about what happened to my family before me, but now... There's a, there's a difference in me now.

Like, I feel complete.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's the end of our journey through the family trees of Questlove, Dr.

Phil McGraw, and Charlayne Hunter-Gault.

Join me when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests, on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: