HOST: ANTIQUES ROADSHOW has made it to the biggest city in Alaska: Anchorage.

GUEST: These photographs are in my hometown area, and some of the people I actually knew.

GUEST: Oh, my goodness. (chuckles) That's awesome.

APPRAISER: Isn't that great?

GUEST: That's fantastic.

HOST: The Alaska Native Heritage Center, which represents Indigenous traditions from all over the state, has been a generous host for our ROADSHOW event.

(man chanting in Native language)

HOST: Song, dance, and sports performances from Alaskan Indigenous cultures can be seen here. (audience applauding) As well as a fantastic collection of Alaska Native artwork. The idea for the Alaska Native Heritage Center was established by the Alaska Federation of Natives in 1987. After over a decade of fundraising and planning, with the help of dedicated community members, the center opened to the public in May 1999. Since it's ROADSHOW's first time in Alaska, to say we're excited to be here today is a huge understatement.

APPRAISER: I think Alaska is fabulous. Where else could you go, and the first thing in the morning, you see a bear going across the road?

APPRAISER: It's absolutely gorgeous place, and the people are so friendly and nice.

APPRAISER: This is my first time in Alaska, but I am definitely coming back.

(people talking and laughing)

GUEST: Hey.

GUEST: I brought an unbound volume by Edward Curtis when he made a trip to Alaska late in his life, like, in the 1920s, and he came along the Western Alaska coast, Nunivak Island to, um, King Island to Kotzebue, where, my hometown. And he also went up to Selawik and to Noatak. It turns out that one of our relatives was his, uh, translator. And so these photographs basically are in my hometown area, and some of the people I actually knew.

APPRAISER: With the, the volume that we have here, you selected a few...

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: ...that were of personal interest to you. I don't think that you had ever looked through this book, had you? Yeah, no. No, I've had it for about 40 years, and so I just kind of stored it away un, until, uh, I heard you were coming to town.

APPRAISER: (chuckles)

GUEST: And so I started taking a look, uh, this morning, actually.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: And I found a particular one that was a big surprise to me. That's my adoptive mother right there. (chuckling)

APPRAISER: It's amazing.

GUEST: In the middle. Her name was Naunġaġiaq in Iñupiat, but her English name was Priscilla. Priscilla Hensley. And so that was, that took me by surprise.

APPRAISER: So you had no idea...

GUEST: No.

APPRAISER: ...that a picture of your mother was in this...

GUEST: That's right.

APPRAISER: ...in this volume.

GUEST: That's right-- the other picture, of course, was this one here. Th, this is the first one...

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: It's the only one that's tinted. It's called Qikiqtaġruk, which means small island. That photograph is probably a matter of feet from where I was born. (chuckles)

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: You know, we had two means of transportation in the summer: one was a "kuh-yuk"-- not "kah-yak," it's "kuh-yuk."

(both chuckle)

GUEST: And the other was an umiak, which is the, the large boat. It had a frame, uh, usually built of driftwood, and covered with seal skins. And the women were able to sew a seamless stitch that did not leak. So you could use those in the springtime, using dogs to pull them on a sled to the open water to hunt.

APPRAISER: And the piece up here?

GUEST: Oh.

(both chuckle)

GUEST: That photograph is very, very important. Before, uh, we had access to wooden barrels, our women turned a seal skin itself into an airtight container with handles on each end. And in there was food. And in, in there would be blubber. In there would be, uh, dried fish cut up, a seal skin dried and cut up, beluga, half-dried and cooked, cut up. There'd be greens in there, and there'd be beluga muktuk, which is the skin-- that was a very, very key food supply. Qikiqtaġruk, or Kotzebue, is about 29 miles above the Arctic Circle, just above the Seward Peninsula. This is, uh, Iñupiat country.

APPRAISER: And we were looking together at the list of illustrations, and they go all the way up the coast.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: So it's not just this region, it's further up.

GUEST: Yes-- these are all natural. I mean, I know that there's an argument about sometimes he kind of shaped the environment they were in.

APPRAISER: Posed?

GUEST: Yeah, and, or... But these are all, pretty much, they're, these are real.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: These are people doing real things.

APPRAISER: Well, you can say that because this is where you're from and you know these people.

GUEST: Yeah, mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: Where did you get this?

GUEST: Oh, I got those in San Francisco. There's a fancy hotel that's been there forever, and within a block or so was this, uh, kind of like a antiquarian bookshop.

APPRAISER: And do you remember how much you, you paid at the time? I mean, that was many years ago.

GUEST: I couldn't have paid... I couldn't have paid much, 'cause I, I was a young legislator, uh, with no family, and we... That was before oil, so we didn't have any money.

(both chuckle)

GUEST: So, so it couldn't have been much.

APPRAISER: The volumes of work by Edward Curtis certainly have a lot of market value. It really depends on the images themselves.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: So it could be, uh, an image that's very, very well-known.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: Um, that could sell for tens, $20,000, and then an image that's not so well-known that, that doesn't bring quite as much.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: It's very subject-driven, and it's, also has a lot to do with size.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: So the works here are in the smaller format.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: So with volume 20, which is what this is, just on its own, probably expecting to see it go for around $10,000 at auction, if everything is in really good condition, which I think that they are.

GUEST: That's wonderful— ah, great. Yeah. I describe my hometown as being 29 miles above the Arctic Circle, 90 miles from the Russian mainland, and 50 miles from the International Date Line, which is tomorrow.

APPRAISER: Tomorrow.

GUEST: Yeah.

GUEST: This, uh, is a box camera that my great-grandfather used to take photographs. He was a semi-professional photographer back in the, uh, tri-state area, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut. And most of the photographs I have were taken in, between 1900 and 1915 or '20.

CREW: Have you ever used it?

GUEST: I haven't, but it works. (laughs)

GUEST: This chair is a part of the living room furniture set that I grew up with. Um, my parents were both teachers with the American Civil Service, and they met and fell in love and got married in Germany back in the 1950s. And so they married in 1955, and in the spring of 1956, they traveled to Denmark a, to purchase furniture set for their first apartment together. And this is a part of that set, and it's traveled all over the world. And this came with me to, first, Texas and then to California, and now it's been with me here in Anchorage for the last 30 years.

APPRAISER: Wow. This chair has a lot of miles on it, doesn't it?

GUEST: It does, yes, it does.

APPRAISER: Holy cow. This chair was made by a very famous furniture designer of the 20th century.

GUEST: Really?

APPRAISER: It... Absolutely. A guy named Hans Wegner.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And he worked out of Denmark.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: And of all the great Danish furniture designers, he is probably the most well-known and the most collected.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: He designed this chair in 1955. So my suspicion is that your parents bought one of the first ones off the factory floor.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: So, the official name of this chair is a GE240.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And there's nothing too sexy about GE240, if you ask me.

GUEST: (chuckles)

APPRAISER: (chuckling) It's sort of industrial. But people in the, in the business have, have referred to this chair as a cigar chair for years.

GUEST: Oh, okay.

APPRAISER: And, and the reason being, is, the arms are somewhat cigar-shaped, and I personally would much rather call my chair a cigar chair...

GUEST: (chuckles)

APPRAISER: ...than a GE240.

GUEST: Well, I can just picture my dad sitting on these, smoking a cigar. (laughing)

APPRAISER: And I think one of the reasons that people loved Hans Wegner furniture was that he very successfully commingled, um, organic design, modernism. If you look at this chair, it just screams Danish Modern, and it's actually in remarkably good condition. I was born in 1956, so chair looks a lot better than I do, I can tell you that.

GUEST: (laughs)

APPRAISER: There are a few wounds it's got, and in modern furniture, unlike some of the earlier period furniture, damage can be fixed without hurting the, the, the value of the chair.

GUEST: Really?

APPRAISER: Um, reupholstering does not affect the value of the chair. You have some, some, a little bit of wood damage over here. Uh, again, you could get that sanded and, and redone, and again, that... And I don't think that's severe enough to have to do.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: But if it, if you were so inclined, you could do that. Mm-hmm. And again, the, the value of the chair is not affected by that-- a matter of fact, you'd probably raise the value of the chair. The back is interesting. I, it, it's not, it's not necessarily quintessential Hans Wegner.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: It, it, it's a little more narrow and a more vertical. I think that's one of the things that people like about it. It's just a s, it's a tad different. Not as different as the arms.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: But, but the back is also slightly different. You had mentioned the orange moving tag. I wouldn't worry about that in the least bit.

GUEST: Okay. And if they don't like it, they can take it off. I tried to take it off myself, and couldn't get it off, and it's such a nice re... I just left it on there as a reminder of all our travels that we've had.

APPRAISER: Do you have any idea what your parents might have paid for it?

GUEST: I have no idea what they paid for it, and I'm pretty sure they couldn't afford much. (laughs): 'Cause they were both teachers and they were very early in their careers, and they didn't have a whole lot of money, so I don't know.

APPRAISER: Yeah, yeah. Well, today, Hans Wegner furniture is really sought after.

GUEST: Yeah?

APPRAISER: Peo, people look for it all over. I just read an article the other day about people going door-knocking in Denmark looking for furniture just like this.

GUEST: Seriously? (laughing)

APPRAISER: Yeah. It's very, very, very much desired.

GUEST: Wow, mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: So value-wise, at auction, just the chair...

GUEST: Yeah?

APPRAISER: ...would probably bring $4,000 to $6,000.

GUEST: No way-- no way! (chuckles) It's a chair! (laughing): Are you serious?

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm, I am serious.

GUEST: That's amazing.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: We should have taken better care of it, maybe. (laughing)

APPRAISER: No, you've taken great care of it.

HOST: This oversized box drum sculpture, made of corten steel, was created by Iñupiat artist Larry Ahvakana in 2014. The sound made by striking a box drum represents the heartbeat of the great spirit bird, or great golden eagle, and is a central part of the last day of Kivgiq, the messenger feast. In this tradition, a messenger was sent from the leader of one community to another with an invitation to partake in feasting, dancing, and gift-giving.

GUEST: This record was given to me because I was an Al Jolson fan and my dad was involved with the beginning of talking pictures. George Groves worked under my father when they were developing the process.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: And he was visiting us in England, and my dad asked him to bring me something of Al Jolson. This record is part of the soundtrack of "The Jazz Singer." It has on it the portion of The Jazz Singer where Al Jolson is playing the piano and singing "Blue Skies" to his mother.

APPRAISER: That was a great part of that movie that we can read about. Al Jolson pops up, and then, to do his live number, and he looks at the crowd and he says, "Wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain't heard nothing yet." And then he goes into this, and the crowd is just shocked, because this is something they didn't ex, didn't know was coming. This was the first talkie, which essentially was the end of the silent film era.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: So we had the first film that had synchronized dialogue and music. This is a Warner Brothers Vitaphone disc. And in this particular movie, they had 15 reels...

GUEST: Oh!

APPRAISER: ...and 15 discs. And here, when we look at close up...

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: ...we'll see that this is disc number six. You may have the only one.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: That survived. We see this is a, a sample record. And so your father was part of the sound production.

GUEST: That's correct. He was a sound engineer, and he developed the method of synchronizing it.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: Making it work.

APPRAISER: Warner Brothers started in 1923. The four Warner brothers were Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack.

GUEST: And Sam was the one that was willing to support my father's work.

APPRAISER: Right, and it was your father's, uh, team that was in charge of making the synchronization happen.

GUEST: That's correct. And the movie contains barely two minutes of this synchronized dialogue and music. And, in fact, most of it was ad-libbed by Jolson. And it was Sam Warner that was the big advocate working on this innovation of the dialogue and sound in synchronization for it.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: Then they were finally, got to the point where they were ready to debut it on October 6, in 1927. And then, unfortunately, Sam Warner died of pneumonia the day before the premiere.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: So we see that it's a, a sample record. It would be somewhere in the process of when they started to work on this tech, new technology, leading somewhere up until, before then, they were to print the albums that were mailed out with the reels. The film itself depicts the story of Jakie Rabinowitz. He was a young man who defied tradition of his devout Jewish family. That, of course, was played by Al Jolson. And the one thing we have to acknowledge about that, as Al Jolson talked about and as essays about the movie have, have come out, is that he wore blackface. Although, at the time, it was documented that it wasn't in, to be in a derogatory or demeaning fashion.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: I think it's probably one of the most important discs relating to the movie business. I'd put an insurance value on it of $25,000.

GUEST: Wow. Thank you very much.

GUEST: I brought in a, a rocking horse, as you can see, and it's a Tom Mix and Tony. And it actually was my neighbor's, and she held an estate sale, so I bought it from her. (chuckles) I paid, like, I think, $200 or $210.

GUEST: Um, it's a bourbon and whiskey flask that my uncle had. And then when he passed, uh, my mom gave us a couple of his items, (laughing): And this was one of them. Um, it's "Pebble Beach, California, "January 10 to 16, 1972. Bing Crosby National Pro-Amateur." And I made sure there wasn't anything in it before we got on the plane, so... (laughs)

GUEST: So I brought today a watch that was given to my father by the president of the, of the University of Alaska System in 1972. I brought it in to a local jeweler who was a Rolex authorized person, and they immediately said, "No, we can't work on this. (laughs) We're sending this to the East Coast." And they didn't want to work on it because of its age, and he, and I can't remember the words he used, but how special it was. He sent it off for me to the Rolex place on the East Coast. While it was there, he contacted me and said, "They want to know if you want a new band." And, um, I think that was the only thing that I said no to. They serviced it, got it all working really well, and I just didn't want to have some new band that hadn't been my dad's band. That he hadn't worn and earned every scratch on there. (chuckling)

APPRAISER: It's a Reference 6263. I looked up the serial numbers. The watch was manufactured in 1969. This is a, a two-button, three-register chronograph. You've got the Oyster bracelet, the riveted Oyster bracelet, which is a lightweight, before they started doing the heavy, solid links. This particular model is a manual wind. The watch is all stainless steel. It's got a water-resistant Oyster, uh, back on it. We have the water-resistant screw-down pushers, or the buttons. You've got the outer black tachometer, uh, bezel for tachometer reading, which would have been necessary for your dad while he was flying and doing aerial survey and such. New, this watch in 1972, would have been $325, $350. Right around there.

GUEST: Yeah.

That's a lot of money. Yeah. When people send these watches in for servicing, they're told, "Well, why don't we sell you a new bracelet?" And, even more so, we see that they want to change the face, because maybe the face was a little scuffy. Maybe some moisture got in there, and it might have discolored. The service dials are not always the same as the original dial that was on the watch. This one here is called a Reverse Panda dial.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: What you did is keep it all 100% original, and by doing that, you increased the value.

GUEST: Oh.

APPRAISER: If they had changed the dial on that watch, that would have made a huge difference. In today's market, this watch, retail, right now, will bring $85,000 to $95,000.

GUEST: Okay. If they had changed that dial, this watch would be worth about $40,000 to $50,000 less.

GUEST: (chuckling): That's amazing.

GUEST: This has been in my family for quite a few generations. My great-grandmother got it in Skagway in the '20s. My mother said it was a wedding gift, and my father said it was purchased, uh, from a Native lady.

APPRAISER: And what do you call it?

GUEST: Chilkat blanket.

APPRAISER: Yeah. And do you know what it's made out of?

GUEST: I think it's made out of goat hair.

APPRAISER: Yes, mountain goat.

GUEST: Mountain goat.

APPRAISER: And also spun cedar bark. It's hard to believe when you feel how soft it is...

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: ...that it's spun cedar bark or mountain goat, for that matter, which are native to this area. Made by the Chilkat. And these weavings are like crests, like a coat of arms, or... Mm. That's what these are. People who would know what these mean from that tribe would recognize, "Oh, yeah, this is so and so's family." You have these ravens. You have a bear. There are several different figures that are on here that make it up, and it has this beautiful blue. Traditionally, it would have been indigo. This is probably a commercial dye.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: And the locks were spun a little bit unevenly, so you can see a change over there in the color, and it's had a little light fading. So if you flip it over... That's the original color.

GUEST: It's so beautiful, yeah.

APPRAISER: So this was very bright when it was created. As far as I know, it's the only weaving style in the world that does these curvilinear forms.

GUEST: Hm.

APPRAISER: You grew up with this hanging on the wall?

GUEST: We did, yeah. Everybody loved it, yeah. It's a, a part of our family.

APPRAISER: That says a whole lot. And the fact that you still have a photograph of it hanging on the wall. Who, who is in the bottom picture?

GUEST: This is my great-grandparents, and they gave the, the blanket to my grandparents, who had it in their house in the '50s, in the '40s and '50s, and we had ours up into the '70s, and it started to lose some of its color, so we decided to pull it off, and, you know, stop that damage from happening. We just rolled it up, and I put it in a closet. And it still looks good, though, you know? But...

APPRAISER: Oh, it's, it's wonderful. These took a long time to make, months and months.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: Judging by the way it's made, the colors, the dye stock, it was probably made sometime between the late 1890s and the 1920s. It is not an adult-sized blanket. It's a smaller blanket, probably for a youth. If this were to come up at auction, I would say probably $25,000 to $30,000.

GUEST: Wow. Wow, that's, that's a lot more than I thought it was gonna be.

APPRAISER: It's culturally a significant piece. If it was worth ten dollars, it's worth taking care of no matter what.

GUEST: Yeah.

GUEST: So, basically, this is high-altitude helmet. It's almost space, but not yet. So I receive this as a present from, uh, my friend. He brought from Soviet Union in the early '90s. He just gave it to me. And there's one interesting thing. There is a last name. In Russian, it says Aksyonov. And when I did my research on internet, it's, actually says that guy went to space. He was, uh, on a space shuttle, uh, Soyuz 22, something like that. So I don't know if it's true, but, uh, I match the last name and match information, so could be quite interesting.

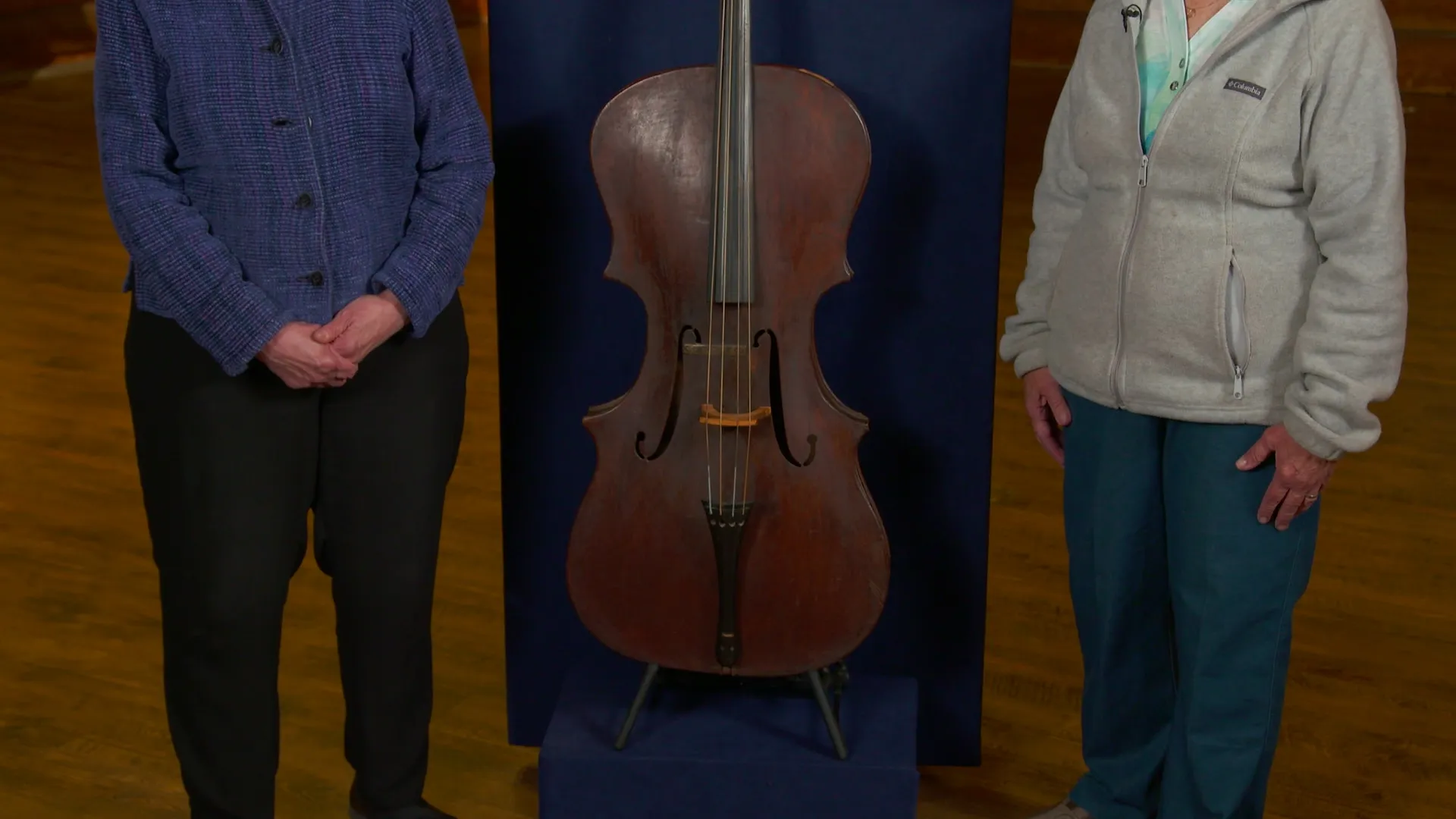

APPRAISER: I'm so glad you brought this instrument in today. I didn't think I would ever have a chance to see one. It's a little bit like bumping into a woolly mammoth, to tell you the truth.

GUEST: (laughs) Five generations back in our family, they were in Nottingham, England, and this was a handmade violoncello, they called it.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: And he played it in the Church of England. They decided to emigrate to America, to Milan, Michigan, is where they ended up. And before they left, they had an auction, and on that list is the violoncello. Apparently, it didn't sell, so they brought it along with them, and it's been in our family ever since. When I moved to Alaska in 1994, I brought it with me, not sure what else to do with it, and we've had it here ever since.

APPRAISER: So, you're right, it's very similar to a cello, violoncello. And it, I saw that auction listing, and indeed, it was referred to as a violoncelli, but it's, actually, it's a bass violin. Now, in the history of musical instruments, bass violins are no longer made, they're no longer played, and they are part of the whole evolution of the violin family, of the bowed instrument family. They're extinct. And they were used a lot for playing in churches because they were loud and they could be heard. And one of the attributes of, uh, instruments that are called bass violins is that the width of the ribs, from, from here to here, it's extremely narrow. It's about a, a half or two-thirds what you would expect in a cello. So from the front, it looks totally standard, and then you look at it from the side, and it looks like it's shrunk a little bit, and that's for projection. So the back is closer to the belly, and the sound comes out, and with much more force.

GUEST: Ah.

APPRAISER: And so that would be perfect for a big, huge church, wouldn't it?

GUEST: Yes-- oh, my goodness.

APPRAISER: They were used up till the 1830s, 1840s, but they were mostly made in the late, uh, 1700s. So this would be an instrument from the 1780s or 1790s. It's in remarkably fine condition for being so old. We will never know who made it. One of the unusual things about it is that the belly is made out of mahogany. Well, I think if you've looked at any violin, viola, or cello, you will see that the top is made of spruce, and so this is mahogany. But what's good about mahogany? The worms don't like it.

GUEST: (chuckles)

APPRAISER: So it's not a particularly resonant wood, but it was made to be preserved. It's a very cool instrument. I think that, in the w, marketplace today, it's not that it has so much value, but it is rare and it's interesting, and your family has preserved it all these years, so bravo. I would value it at, at a price that would reflect what a cello, a basic cello would be worth today, and that's about $1,500 to $2,000.

GUEST: Oh, my goodness.

APPRAISER: In the retail market, yeah.

GUEST: Uh-huh. Okay, well, we mostly wanted to know about it, and that's exactly what you've shared.

GUEST: So these are maps of the Matanuska Colony Project that was one of the work projects following the Great Depression to get America back to work. They brought people up to try and populate and develop an economy in Anchorage and in the Matanuska Valley, which is about 40 miles north of Anchorage. These maps show each one of the families' parcels. My husband's parents were both colony kids. His mother came up from Minnesota and his father came up from Wisconsin. And we purchased the family's farm from his paternal grandmother in 1995. The farm is, uh, number 26 on the map.

APPRAISER: Excellent.

GUEST: And we still farm it as a family.

APPRAISER: How did you acquire the maps?

GUEST: The maps originally belonged to Senator Jay Kerttula, and he was also a colony kid. And when Senator Kerttula passed away, his daughter was cleaning out all of his things, and she hired my son to help go through stuff.

APPRAISER: Oh.

GUEST: And these maps were in there and she gave them to my son.

APPRAISER: Well, they're manuscript maps, and what's interesting is, you've got two different dates here. You've got the, the earlier one, 1929, which grades the land. You've got good land and fair land. And the colony was quite experimental, because Alaska was a territory. At the time, it was the Great Depression, and everyone was suffering. As part of the New Deal, I think it was about 200 families from the Midwest...

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: ...were offered land up here, and they were invited to colonize Indigenous land.

GUEST: There was a, a Native population that, that lived and hunted.

APPRAISER: Okay.

GUEST: This was all Dena'ina land. Wasilla was the, uh, the name of the chief in, uh, in Wasilla, and that's what that community is named after. The names on here were homesteaders who had been there since, in, in the 1800s, prior to the colonists coming in. I'm not sure how the land was transferred to the homesteaders. In Indigenous culture, they don't own land. So that was one of the, the problems is, they couldn't prove that they loaned the, owned the land, because they didn't have title to it. But that's not how the Dena'ina culture or the Native cultures in Alaska work-- or anywhere, probably. And so it was a problem for the, the Native people, and, and it still is a, a point of controversy. We don't want to ignore the fact that it, the Dena'ina people were here first, and so...

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: ...that needs to be recognized. This is actually probably the best farmland in Alaska, is in, is in this area. From what I understand, the 200 families that came up, about half of them left after the first couple of years. The project required that the people had to actually earn a living from the farm. And the problem was, there wasn't the population to actually be able to sell the produce. So, um, when World War II happened, there was a big military buildup in Anchorage and in Fairbanks, which brought a lot of, uh, military people up, and that created the economy that the farmers needed to actually start making money from the farms.

APPRAISER: Value-wise, these are completely unique. They're manuscript, they're engineering plans. And as a set, in a, in a retail setting, in a gallery, I could see selling the maps for $5,000.

GUEST: Wow.

APPRAISER: Thank you so much for bringing them in.

GUEST: Well, that's really interesting. Yeah, thank you, it's really good to learn a little bit more about them.

GUEST: It's a Telecaster, Fender Telecaster. I'm not sure exactly what year it is. I think it's, uh, early '60s, '64, something like that, maybe. I bought it in a secondhand shop years ago, uh, probably back in... The '70s? (stammers): Early '70s? For about $100.

GUEST: These are my grandfather's, uh, goggles from flying a Jenny in, uh, 1920s. It's a Major-- it's, uh, S, company, Strauss and Braumeier, I believe. And I have no idea how old they are, but they're at least 100 years old, so... (chuckling)

GUEST: When I was a student in Boston 50 years ago, I was walking down Newbury Street, and, uh, there was a crowd outside this bookstore. Gahan Wilson was out there with an easel and drawing paper and taking suggestions from people about what to draw.

APPRAISER: Wow. So you threw out a suggestion?

GUEST: I know he specialized in a lot of monsters. Everybody knows Frankenstein and Dracula, but I said, "The Gill-man," the, the Creature from the Black Lagoon.

APPRAISER: (laughs)

GUEST: And that's what he came up with.

APPRAISER: So when you saw the crowd and saw what he was doing, did you know who it was as, as soon as you got there?

GUEST: I think there was a sign.

APPRAISER: Okay, yeah.

GUEST: 'Cause I didn't know his face, I only knew his work.

APPRAISER: So you, you had heard of him before?

GUEST: Oh, definitely.

APPRAISER: Okay, great, great. First of all, the fact that he did this on the fly from people, from you throwing out suggestion, is amazing, and also reflects what everyone has come to know and love about Gahan Wilson, who was a illustrator, an author, a cartoonist, a humorist. Uh, he also did, uh, reviews, uh, movie reviews, kind of, kind of to pay the bills.

GUEST: I didn't know that.

APPRAISER: Yeah, he was a, kind of a jack-of-all-trades. And when he died, uh, 2019, he was hailed as the master of the macabre, the wizard of weird. And his cartoons are often based on fantasy and science fiction and horror in a very kind of, uh, dark-humor kind of way. You've got this unknown character feeding the Creature from the Black Lagoon fish food, and he's kind of in a fishlike bowl, and putting the Creature from the Black Lagoon into a different light. He was out there doing this. Was he, was he charging for these drawings? Or how was it working?

GUEST: I can't remember, it was long ago.

APPRAISER: (laughs)

GUEST: It may have been a couple of bucks or it may have been just, "Here, kid, you can have it."

APPRAISER: Got it, got it. Actually, bold signature, which is typical of his signature, so it's good that he did that, too, 'cause it also adds to the value. Wilson did cartoons for The New Yorker and for National Lampoon, right? What you'll...

GUEST: And Playboy.

APPRAISER: And Playboy. What you will often see are finished cartoons that were used, camera-ready art, that then got put in a file somewhere. And they're all going to be maybe ten by ten, or ten by 15, something like that. What year would you think that would have been?

GUEST: '72 or '73.

APPRAISER: '72 or '73, so fairly early. I would say that at auction, we're talking about $1,500 to $2,500.

GUEST: That's a, that's a surprise.

(both laugh)

GUEST: The creature looks so cute and adorable there. (laughing)

APPRAISER: Exactly. Not such a bad monster once you get to know him.

GUEST: Yeah, that's right.

HOST: In front of the semi-subterranean Sugpiaq model home, called a ciqlluaq, are the lower jawbones of a bowhead whale, just one-third the size of the entire animal. The Sugpiaq people in the southern part of the state historically were whalers who hunted in the Gulf of Alaska. Whale jawbones were used as land markers on beaches for those at sea.

APPRAISER: What can you tell me about this wonderful Rusty Heurlin?

GUEST: Well, I know my grandfather got it commissioned back in 1964. They were living in Fairbanks, and they took the family on a drive down to Ester, where, uh, Rusty lived and, and worked. My dad was about ten or 11 back then. He, he remembers faintly, but, uh, my grandfather went in a separate room with Rusty and discussed what kind of painting he wanted. And then they left, and about, uh, three months later, they had this, uh, nice painting delivered to their home.

APPRAISER: So now you've lived with this painting all your life.

GUEST: Yes, my, of course, my grandfather had it, um, passed it on to my mom and dad. They gifted it to me and, and my wife last year. So we have it hanging in our house. It's, uh, definitely has a lot of sentimental value. My parents grew up in Fairbanks, I grew up in California. They moved down, um, down to California in the '80s. But I always grew up hearing about Alaska, and wanting to, to go explore and, and move back, and this, this painting was part of it. It just really captures the mystique and the frontier of Alaska. So I always had this in my mind of, of just going to the unknown, and then I finally moved up, uh, when I was 18, and, um, and made the dream come true, yeah.

APPRAISER: So have you ever seen the Northern Lights?

GUEST: I have, yes. How close is this? It's hard to capture it, but it's, it's close. It, it's close-- it definitely brings back that feeling of, of seeing the lights for the first time.

APPRAISER: Rusty was born in Sweden-- his parents were visiting there-- in the late 19th century, and his family moved to the suburbs of Boston. And he studied art at the Fenway School of Illustration. He first came to Alaska in 1916, and then was in the military for a while, and then came back and stayed until he died at the age of 90, in 1986. He loved Alaska, obviously, and this painting is what makes Alaska Alaska. The snow, the musher, the Northern Lights. The palette-- uh, it's a really gentle, subtle blue. What I really like about the painting is, he really was able to capture quiet. That's an amazing accomplishment to me. It's oil on canvas. He's using his middle name, rather than Rusty. Painted in, as you said, 1964. Do you have any idea what he paid for it?

GUEST: I don't know-- I don't have a dollar figure. I, I can't assume it was a, a cheap, uh, painting. Back then, he was quite well known, Rusty was.

APPRAISER: Did you know that the Anchorage Museum has a piece quite similar to this? Oh, no, I didn't know that. Yeah, they have a number of his paintings. I would give it an auction estimate of between $40,000 and $60,000.

GUEST: Wow, that's more than I thought. (chuckling)

APPRAISER: And for insurance... Mm-hmm. ...I think maybe around $75,000.

GUEST: Okay, wow. Was not expecting that. (chuckles) That's quite astounding. Don't plan on selling it-- it's, it's a family piece.

GUEST: My husband, um, actually found this in a local antique store. He really liked it and pointed it out to me, and we left that day without purchasing it. But he had a birthday coming up in a couple of weeks, so I snuck back a couple of days later and bought it for him for his birthday, and know absolutely nothing about it, other than that we thought it was just really awesome.

APPRAISER: Okay, well, it's Italian, it's Art Deco, dates from the 1920s, maybe into the 1930s, and it's made of alabaster. And alabaster has been a very sought-after material for c, millennia. It's been mined in Ancient Egypt, and used in, you, we find examples of things made of alabaster in the pharaohs' tombs. It became a popular carving material in Italy in the late 18th century. Its popularity is because it looks like marble, but it is much softer to carve...

GUEST: Hm, that makes sense.

APPRAISER: ...and it's actually more carveable, like wood. The major mines in Italy are, uh, up in the Tuscany area. This was probably, uh, exported, made for export, and sold probably in the United States in the 1920s.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: A lot of these could have come with, uh, paper labels on them, and they often come off, but they did not necessarily label wi, with a maker's name.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: And it's so whimsical. It has three bears, you know, one clearly the leader of the, of the group, standing on top of the ice cave, and the icicles falling down, and the two smaller bears. It's nice that they chose a little bit different color for this bear, which indicates it's, you know, has a different color of its fur.

GUEST: Yeah, it's a light.

APPRAISER: It's a lamp-- it does light up. And, uh, in a dark room, it would make a, a big statement.

GUEST: It's very stunning, yeah.

APPRAISER: I get that.

GUEST: In a dark room.

APPRAISER: The cord on it is a little... A little...

GUEST: (laughs): A little shady, yeah.

APPRAISER: Yeah, I mean, I don't know about-- for safety issues, you might want to have it rewired.

GUEST: I know. (laughs)

APPRAISER: And that won't cost very much.

GUEST: In fact, my husband said that before I left this morning. He's, like, "Make sure you tell them that I know the cord's not right."

APPRAISER: Do you mind me asking what you paid for it?

GUEST: I believe I paid $120 for it.

APPRAISER: Okay, well, I saw in the retail level at least three examples of this same model being offered at in excess of $2,000.

GUEST: Oh, my goodness.

APPRAISER: (chuckles)

GUEST: That's awesome.

APPRAISER: Isn't that great?

GUEST: That's fantastic.

APPRAISER: I think you got a great deal.

GUEST: Yeah. Yeah, and I think my husband's maybe going to have to step up his birthday game this year.

(both laugh)

GUEST: Shh-- secret!

(both laugh)

GUEST: I brought in my mom's Beatles necklace. My grandfather gave it to my mom for her high school graduation, and she showed it to me. It's got a lovely snap on the back, and when you open it up, you open it up to all of the Beatles. Oh, and it just ripped. But you open it up to all of the Beatles inside.

APPRAISER: If there was one artist that I would have expected to find in Alaska, it's probably this chap here.

GUEST: Yup. (laughs)

APPRAISER: Do you want to enlighten us and tell us who that is? That is Sydney Laurence.

GUEST: He's quite a famous Alaskan artist, although he came from England. Made quite a life for himself here. My husband's great-aunt was a friend of his. And that's how this picture got into our family. (chuckles)

APPRAISER: I'm going to correct you on one thing there.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: It was almost the opposite of England.

GUEST: Oh, it was?

APPRAISER: Brooklyn.

GUEST: Brooklyn? He came from Brooklyn?

APPRAISER: (laughs) Brooklyn, born and bred.

GUEST: Oh!

APPRAISER: 1865, yes.

GUEST: (exhales)

APPRAISER: But you're, you're almost right, because he spent about 15 years in England.

GUEST: Oh, okay. (laughs)

APPRAISER: He was there at the time with a wife and two children, and then he, uh, let's say, pulled a Gauguin and disappeared.

GUEST: Hm.

APPRAISER: And came off, came to Alaska around about 1903, 1904.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And he was a gold prospector at that time. Quite a colorful character.

GUEST: (laughs)

APPRAISER: Because, uh, before he was doing that, he was in Africa.

GUEST: Oh, wow.

APPRAISER: During the Boer War. He was a wartime correspondent and artist.

GUEST: Oh.

APPRAISER: So he covered the Boer War. He was in China during the Boxer Rebellion. And also in Africa, he covered the Zulu Wars, and in fact got clubbed, which led to him losing hearing in one ear.

GUEST: Oh, wow.

APPRAISER: So he had quite a colorful life, as I say, but circumstance or choice led him to Alaska. He was the first professional artist to really set up stall here, and this is one that he did here.

GUEST: Yep.

APPRAISER: He was in Anchorage from about 1920 onwards. The frame here... Mm-hmm. ...appears to be original to me, and particularly with the label in the back.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: Which is clearly the artist's label. "'Indian Fish Cache,' Sydney Laurence, Anchorage, Alaska." And then right down here, slightly less visible, "Dolly Crawford, 1922." And tell me about Dolly Crawford.

GUEST: She was my mother-in-law's, uh, mother's sister. So she was his, her aunt, his great-aunt, and she came to Anchorage. I don't know a lot about her. She came to Alaska and lived here for a, quite a long time.

APPRAISER: So do you know whether this was inherited within the family, or was it, was it bought?

GUEST: Yes. It was given to Dolly and then it went through part of her family, and they didn't live in Alaska at that time. And my mother-in-law loved the picture and she bought it from them.

APPRAISER: Ah, I see.

GUEST: But we don't, I don't know how much she paid or anything like that-- it was quite a long time ago.

APPRAISER: All right. And, of course, he was really famous for the paintings he did of Mount McKinley, or Denali, as it's known now.

GUEST: Yes, those are beautiful.

APPRAISER: Those enormous snowscapes. So, this isn't quite that. No. (laughing) But this is a, another subject. Can you tell us what this is?

GUEST: This is a cache, and it's what was used to, um, store food and things like that to keep the animals from, um, from getting 'em.

APPRAISER: And we see the, the fish, the smoked fish, I would presume, here.

GUEST: Yep.

APPRAISER: And this would be done in the springtime, looking at the, the colors. It's got a lovely light tonality to it.

GUEST: Mm-hmm. Some of his works could be quite dark, and I, I love just the little flourishes of brushwork that he's done and the flowers that you see here, the little dashes of paint that he's used to describe those. You don't see fish caches many places.

GUEST: No. (laughing)

But I think just over in the distance there, there's one, actually. And have you given any thought to the value of it?

GUEST: Well, my husband said he thinks it's worth $25,000, and I said-- he wanted to know what I thought. I go, "I have no idea." (laughs): "At all!"

APPRAISER: Is he quite an optimistic fellow, your husband?

GUEST: Yes. (laughs)

APPRAISER: I thought he was. At auction, I believe it would make somewhere in the region of $8,000 to $12,000.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And if you wanted to insure it...

GUEST: Mm-hmm?

APPRAISER: ...I would suggest around about $20,000.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: So he's not too far off.

GUEST: No-- oh, I was wondering about that, yeah.

APPRAISER: A little ambitious.

GUEST: Yeah. 'Cause it's not insured. (laughs)

APPRAISER: Yeah, you ought to have it insured.

GUEST: Yep.

APPRAISER: And it's, it's a lovely painting.

GUEST: So these, uh, snowshoes I actually got from my grandmother's garage, and, before she, uh, moved out of her house in Willow. Um, I believe she had them for quite a while to kind of walk around their property. And they're not actually a matching set, which I didn't even realize until we brought them in, so... But they're pretty cool nonetheless.

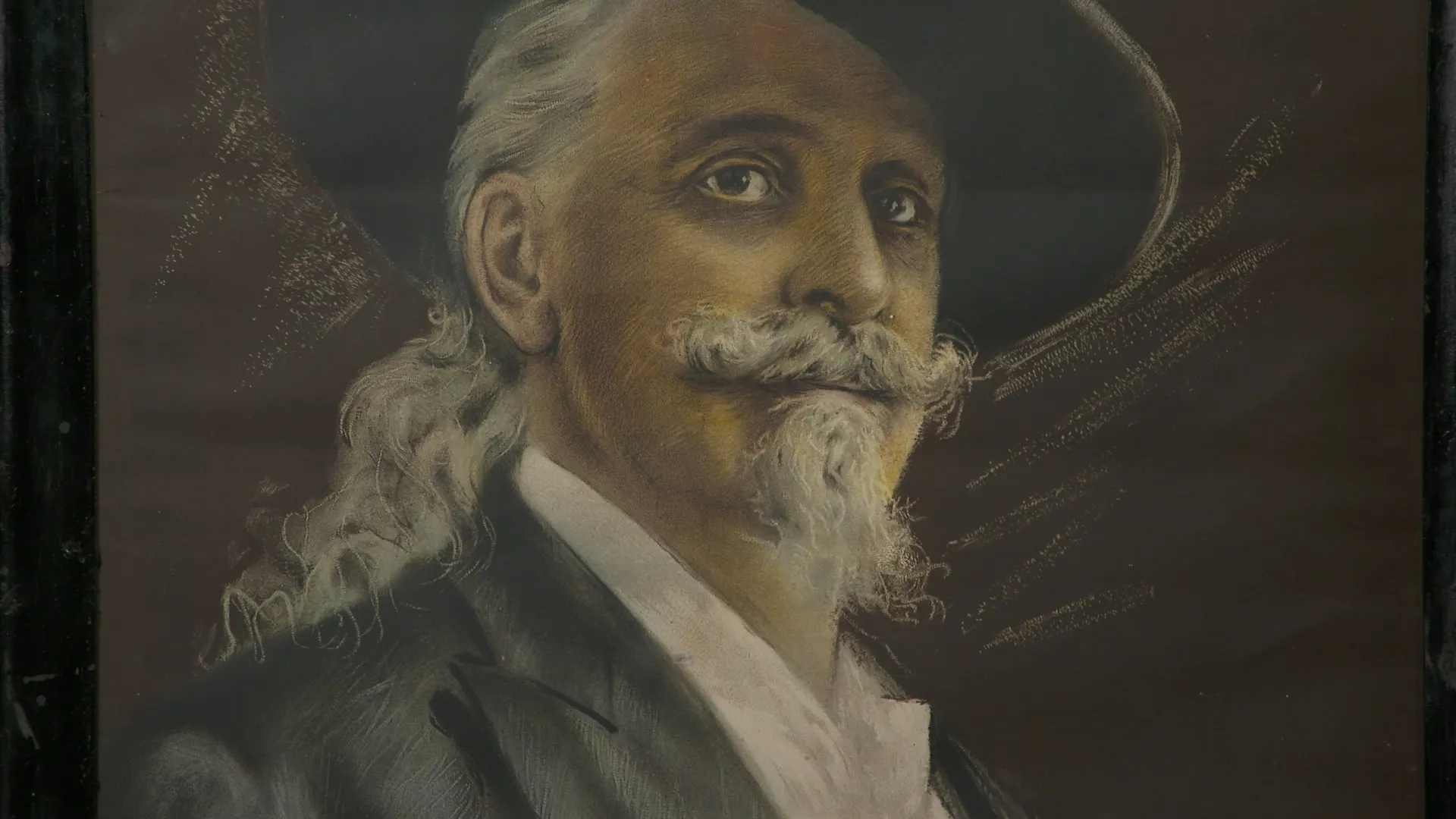

GUEST: It's a print of Buffalo Bill. It was given to my great-grandfather. He immigrated from Italy to Pueblo, Colorado, and they lived on the mesa, and then went by wagon train to Greenhorn. They had bought some property there. It had a well that was the only water between Pueblo and Walsenburg on the old highway. It was said that when the stagecoach was running, Buffalo Bill came through, he took a liking to my grandfather, and gave him this picture, and they hung it in the restaurant that was there.

APPRAISER: Fantastic-- when would that have been?

GUEST: In the 19, early 1900s.

APPRAISER: In his era, Buffalo Bill was the biggest performer and the biggest name and one of the most famous people in the world. The fact that he was so well-known was word of mouth. It was newspapers.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: There were no radios, and it was posters. So Buffalo Bill began his career as a scout and a plainsman on the plains. He was a buffalo hunter.

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: That's where his name comes from. Uh, he ran with the Pony Express for a short time. He was in the U.S. Army for a little while. And eventually, taking this legitimate colorful background that he had...

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: ...uh, he started up his own Wild West show, "Buffalo Bill's Wild West."

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: And when you brought it in, I, I saw it, and I was, like, "Buffalo Bill is so famous, "and his posters helped make him famous. And I know a lot about posters."

GUEST: Mm-hmm

APPRAISER: "And I know a lot about Buffalo Bill. But I've never seen this image before."

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: And I was, like, "That's unusual," because I thought I'd, I thought I'd seen it all.

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: Buffalo Bill was a showman, and he would always dress as a frontiersman.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: He was a fancy frontiersman, with his buckskin jackets and his cowboy hat. But here he's dressed a little bit more like Johnny Cash. He's... Hm?

GUEST: Yeah, very subdued, yeah.

APPRAISER: Almost funereal, right?

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: So I thought, "Oh, maybe this is a posthumous print."

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: But then you look at it and it says "Yours, cordially," you know, "Colonel W.F. Cody (Buffalo Bill)." So it's while he's still alive. And then I looked cl, more closely, and it's really faint, but in the lower right hand corner, you can see that it was printed by the Currier Litho Company in Buffalo, New York, and it's dated 1907.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: So this is a 1907 lithograph. And, and Bill, although... You know, he died in 1917. By 1907, his career was not as large as it had been a, a few years prior to that.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: But he was still performing. What do you think this is worth?

GUEST: I tried to get it appraised once, and it wa, they said it was anywhere from $200 to, it could be more.

APPRAISER: That's a very general appraisal.

GUEST: Yeah. (chuckles)

APPRAISER: (laughs)

GUEST: It was. But we just, I love it, and, uh, it's been a part of the family forever.

APPRAISER: I think that if this were to come to auction without the printer's mark on it...

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: ...people wouldn't have the actual historical context, the date in which it came from.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: And I think having the Currier Lithograph mark on it and the date 1907 really helps add that extra level of, of context, authenticity, and value. If this was Bill on his horse...

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: ...if this was Bill in a fictitious recreation of some famous battle that he did...

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: ...it might have some extra appeal.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: Buffalo Bill really is one of the, still one of the top marquee names in collectibles.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: At auction, I would estimate it between $4,000 and $6,000.

GUEST: Okay. Well, thank you. It's going to still have a, its favorite place at my house. (laughs)

APPRAISER: And it's one of those things, because it's so rare, it wouldn't surprise me if it went even higher.

GUEST: Uh-huh.

HOST: Incredible baskets from various parts of Alaska are on display in the Hall of Cultures. An Unangan maker from the Aleutian Islands wove this small, lidded example in the 1880s. Made from beach ryegrass with a delightful snowflake motif, the weaving is so tight, it can hold water.

APPRAISER: We don't often on the ROADSHOW get to talk about female heroes.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: So I could not be more thrilled that you brought in this 1990 first-place championship trophy for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race won by Susan Butcher, your wife!

GUEST: Yes. Susan and I met out on the Iditarod trails. We just, uh, got stuck in a snowstorm and met in 1981. Susan was born in Cambridge, Mass.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

GUEST: And she always loved dogs-- it was her passion. And so she became a dog walker. And because she loved it so much, her mother bought her, um, a sled. And then they moved up to Maine, where her grandmother lived, and then got one dog, and then moved to Colorado, where her father was, and started mushing in the mountains there, and thought it was great, but it wasn't wild enough for her. So then she moved to Alaska in about 1974.

APPRAISER: This is a marathon-- it's a thousand-mile race.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: Yeah. What are some of the challenges or issues that, that you could encounter?

GUEST: Weather is your number one. Could be super-cold, let's say 40 or 50 below zero. You have to be able to protect yourself, but also protect the dogs.

APPRAISER: Susan won '86, right? '87, correct?

GUEST: '88.

APPRAISER: Uh, '88, and then got second in '89. This was Susan's fourth win...

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: ...in 1990 for the Iditarod. It seems to me she had an extraordinary record. 17 races.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: Scratched once, 19th in her first, but top ten the other 15 times? How was it for her being a woman out there with largely men? How was she perceived? How was she accepted?

GUEST: It was very difficult. There was a lot of, sort of, I'd say resentment, because people hadn't come to respect her abilities.

APPRAISER: She set the record and broke her own record in, in 1990.

GUEST: She...

APPRAISER: She broke her record, with...

GUEST: She, yeah.

APPRAISER: ...11 days, one hour, 53 minutes.

GUEST: Yeah, right.

APPRAISER: What do you think her legacy was...

GUEST: Well...

APPRAISER: ...in regard to the Iditarod?

GUEST: You know, I think Title IX, if you remember that.

APPRAISER: '72.

GUEST: Of course-- you know, it was quite a turning point in women's sports and just the evolution of how you thought about it. And Susan, uh, then became, because she competed in a field with men, kind of an icon of that experience. She was representing the ability of women to compete on an equal level.

APPRAISER: She retired in 1994. Right. Why did she decide to retire?

GUEST: She decided to retire 'cause we wanted kids. And the next year, we had a beautiful daughter, named Tekla, in 1995. And then we had another one, her name is Chisana, which is the name of the place that Susan lived in the Wrangell Mountains.

APPRAISER: Susan really transcended sport.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: And she was at the top of this, 'cause there's only a handful of mushers who have won the Iditarod four times.

GUEST: Yes. And I think there's only one that's won it five times. Unfortunately, Susan passed away in 2006.

GUEST: Yeah, yep.

APPRAISER: But she leaves the legacy.

GUEST: After Susan had passed away, I still wanted them to know what it was that their mother loved. So when they were 11 years old, what I did is, I got them, we trained up dog teams and we took some friends and we mushed all the way to Nome. And my younger daughter sees the aurora over her head and she sees an animal around the corner. She sees birds flying, and she goes, "This is why Mom loved it."

APPRAISER: I heard that there's a T-shirt out there that says, "In Alaska, men are men and women win the Iditarod."

GUEST: Yeah, yeah. (chuckles):

APPRAISER: She, she's an Alaskan hero to all. I also think that there are a number of, of huge fans of the Iditarod in its 50 years of existence, from 1973 to 2023.

GUEST: Yeah, yep, yep.

APPRAISER: So it's a narrow but very passionate group...

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: ...that would be collected and would be interested, particularly since it's the last trophy that Susan won, her own legacy, and the fact she won it four times. I would put an insurance value of $100,000 on this trophy.

GUEST: (coughs out): No way! (laughing): No way-- no way! Well, give me the insurance company's name.

(both laugh)

APPRAISER: If you were ever going to auction it off, it'd be $50,000 to $75,000 for an auction estimate.

GUEST: Uh-huh, wow.

APPRAISER: But obviously, priceless.

HOST: You're watching ANTIQUES ROADSHOW from the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. Get more ROADSHOW at pbs.org/antiques, watch on the PBS app, and follow @ROADSHOWPBS for exclusive content, updates, and special features. Watch more now from the Feedback Booth right after this.

HOST: And now it's time for the ROADSHOW Feedback Booth.

GUEST: We brought this hideous alligator purse. I think it's cute.

GUEST: Great-grandma's, and my great-grandma's ruby ring, which is actually synthetic, but real gold. And we had a great time.

GUEST: I have, um, a set of these sake cups that my, um, my husband's grandma got in Japan in the 1950s, when they lived there. Um, and when you add sake to the cups, it's a little naughty inside. A little naughty picture of, like, a male and a female, you know what I'm saying? (laughs) And the lady who appraises, she's, like, "Oh, my goodness! I've never seen anything like this!" And I'm, like, "Oh, is it worth a lot of money?" But they're, like, $70, I think she said, so...

GUEST: But... We were, we're here for the fun of it, so... Cheers! Cheers!

GUEST: I brought these campaign buttons today that my grandfather gave me. They're worth... (grunts): Maybe $50. Uh, they're not in very good condition. But most importantly, I got to live my best life and be on the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, which is something that I have always wanted to do since I started watching the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW when I was, like, ten years old. So this is the best day.

GUEST: And it, it turned out that our 53-year friendship was worth more than anything we brought to the ROADSHOW today. (laughing)

GUEST: We had a wonderful time. Didn't get anything to land us on TV. Oh, wait, we are on TV! But my little doll was worth $400. And we learned that this deadeye that we found on the beach, we can make up whatever story we want about what kind of ship it came from. (laughing) Thank you, ANTIQUSE ROADSHOW. Our favorite antiques are still each other.

HOST: Thanks for watching. See you next time on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW.