10/24/23 | Students Share What Makes Maui Strong

Season 15 Episode 1 | 28m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

EPISODE 1501

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, Maui HIKI NŌ students share what they cherish about their beloved island and reflect on the common mantra echoing across the islands: “Maui Strong,” following the devastating wildfires that affected Maui in August 2023. EPISODE 1501

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i

10/24/23 | Students Share What Makes Maui Strong

Season 15 Episode 1 | 28m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, Maui HIKI NŌ students share what they cherish about their beloved island and reflect on the common mantra echoing across the islands: “Maui Strong,” following the devastating wildfires that affected Maui in August 2023. EPISODE 1501

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch HIKI NŌ

HIKI NŌ is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[intro music] HIKI NŌ, Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

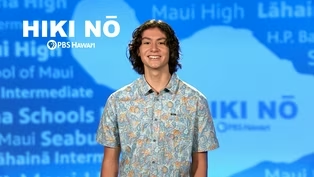

Aloha and welcome to this week’s episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

I'm Samuel Paci and I'm a senior at H.P.

Baldwin High School.

Mahalo for joining us.

Throughout high school, I've had the chance to tell stories about my home on Maui and share them with you here on HIKI NŌ.

I've covered an array of stories, such as a feature story about a unique record shop and another about a mural art movement in Wailuku.

Maui is an incredible island, and I'm so proud to have been born and raised there.

So, when a fire destroyed the town of Lahaina and damaged so much of our home island in August, we were in shock.

The night of August 8, all my family and I could see from our home in central Maui was a giant blaze of orange Upcountry and out in Kihei.

When my stepdad, who is a firefighter, came home a couple days later, that's when it really hit me.

His hometown Lahaina, and the hometown of so many of our people was gone.

It affects all these people who grew up there personally.

And not only the people who grew up there, but people like me, who would go to the beach there or visit and enjoy its culture and history.

In this episode, we wanted to honor Lahaina and the island of Maui by sharing memorable stories from the HIKI NŌ archives, some of which are now time capsules of our historic Lahaina.

And all of these stories spotlight what makes Maui unique and special.

In addition, we'll hear from Maui HIKI NŌ students who want to share what they cherish about their beloved Island and reflect on the common mantra echoing across the islands: Maui Strong.

As an island community, we are still grieving the lives lost.

We know recovery will take time.

But ever since the fire, everyone I know has been helping out.

We volunteer at shelters and give everything we can.

Honestly, it feels like there's more unity on our island than ever.

That's why I want to turn to my fellow Maui students.

Let's listen to what they had to say about what makes Maui, Maui.

Maui, a place where family and community runs deep.

No matter where I go, I will never forget where I am from and the lessons Maui has taught me.

We have persevered through the recent disaster.

With all the hardship the community of Lahaina has gone through, they have continued to move forward, leaving no one behind.

I have seen many people in the community help in any way they could.

The community has held strong through thick and thin while helping others during and after the fires.

People risked their lives to save others and the island.

Many donated food, water, and shelter to those who suffered.

We have many cultures.

We are different, but still united and support each other.

Go Lunas!

I am proud that Lahaina is healing and that people are joining and helping out.

Growing up in Lahaina I have a lot of pride.

Whether it's because of sports or because my family's from there, too.

I remember when I was little, whenever I would walk down the street, I could hear people referring to each other as brother, sister, auntie, or uncle.

I'm happy to have neighbors who are caring.

What Maui Strong means to me is that we're going to get through this tragedy no matter what and we will still be standing.

With everything that has happened, our community has been awesome because we all came together and helped each other out.

Maui is special because this is where my ‘ohana is.

I have great friends who share and play with me.

My neighbors are friendly and will treat each other with kindness.

This is why Maui is special to me.

On this island, I have truly become who I am.

Maui is where I was born and raised, and I would never want to leave.

Everyone is trying to make sure the community is okay.

It doesn't matter if they know each other personally or not.

Everyone is trying to do what they can to help.

This is why I'm proud to be from Lahaina.

[chime] HIKI NŌ students are so eloquent, no matter their age.

We hope their voices provided you with some hope.

I was in a class at H.P.

Baldwin High School when we received the invitation to submit stories from Maui for this special episode.

I immediately knew who I wanted to interview: a firefighter who was in the thick of it during the fires in August.

In this next piece, I interview Ray Watanabe who also happens to be my stepfather.

I mean, there's no words to describe the fires that, uh, devastated the whole town of Lahaina.

In August 2023, Maui firefighters were called to duty to fight not one, but three fires on Maui.

Ray Watanabe, my stepfather, was one of them.

My role during the Lahaina wildfire, cuz there were three separate fires going on at the same time - my role was, uh, driving a relief truck through the Lahaina area and assigned to the Wahikuli district.

Although he's a current resident and firefighter at the Kahului fire station, his connection with Lahaina is personal and runs deep.

Uh, growing up in Lahaina was awesome.

Um, I had a twin brother.

So, you know, we did a lot of things together.

I came from the old Pioneer Mill area.

We had our little, little rat pack, I want to call it, of guys and gals, girls, and then we just hung out and played and just did, did a lot of things together.

Like normally kids cannot, can't do today.

As you know, Lahaina is a small knit community.

Everybody's pretty close on a daily basis.

This affected a lot of people, including myself.

I don't live in Lahaina anymore, but it, it affected me a lot.

Because I know family and friends still missing, things of that nature.

Since the fires, Watanabe and his colleagues have been a part of another way to give to the community: volunteering in schools.

He says it's been a healing outlet for everyone.

I was, was asked to volunteer and read, read to, uh, children up countries, at one of the country schools.

And that was great because we get a lot of support.

But the kids were really appreciative, um, of the work we did up there and that, it really hits home when they tell you thank you and stuff like that.

Despite the challenges of being a firefighter, Watanabe says he enjoys his job and will continue to support his community throughout his years.

There's always going to be a lot of, um, negative experiences.

But to me, the positive outweigh the negative experiences, especially when you help people and not getting any kind of reward from it.

I just, I just enjoy what we do.

The people that I've run in from Lahaina have been very kind to me, keep on telling us to keep doing the good work that we do.

This is Samuel Paci from H.P.

Baldwin High School for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

[chime] Now, I'd like to share a story that was produced by the students of Lahaina Intermediate School prior to the fire that displaced them from the campus.

Their report explores how their school became among the first public schools in the state to make an eco-friendly switch in their cafeteria.

At the time of this recording, they were set to return to the campus in mid-October.

I think they're really good.

I think it really like, it helps the environment a lot and it's probably less money for the school.

In the late 80s Hawai‘i public schools did away with washing trays and utensils and switched to one-time use products.

Since then, schools have been throwing away the trays, utensils and food waste in the trash, which ended up in the landfill.

In November 2022, Lahaina Intermedia became the first public school in Hawai‘i to pilot the Zero Waste program in the cafeteria.

They installed a dishwasher and made the switch back to reusable plastic trays and metal utensils.

Think about it.

We have over 600 kids in our school.

That means 600 forks and 600 trays are being sent to the landfill every single day.

Multiply that by the five days of the week, and you get 3,250, which is approximately 13,000 forks and 13,000 trades per month.

And this is only for lunch.

If you include breakfast and second meals, that number gets even higher.

We're just one school out of the 295 schools in Hawai‘i.

That is a lot of plastic waste.

Uh, yes, I believe, uh, it’s, it's really a good change that we went from the disposables to the plastic.

I think it's great for the environment.

Well, it's more work for us.

It takes almost, almost two to four people to run the dishwashing machine because of all the drying and the cleaning.

Because it's a, it's a pilot program, we were willing to start it and see how it goes.

I actually like it.

It does take work, but I think that it's a good way of moving forward.

Lahaina Intermediate is the first one in state that's limiting our, um, uh, our landfills so I think it's a good program.

This new program will definitely take some getting used to.

Prior to the switch, Lahaina Intermediate, like many other schools, has had a shortage of substitutes.

This has led to having multiple classes in the cafe during the school day.

With our new lunch system, students need to eat in the cafeteria to ensure that trays and utensils get returned and washed in time for the second lunch period.

Teaching simultaneously while having lunch is more difficult recently because with the new lunch trays, they're making everybody eat inside the cafe.

Before when people could eat outside, that was nice because it was just the classes in there.

Now with everybody eating lunch, um, it's just really loud and the people eating or talking so the kids that are supposed to be learning, it's not a good learning environment for them.

Although it is a change for the students, many feel that the benefits outweigh the inconveniences.

Instead of throwing away everything, and then with the plastic trays you can always reuse them and wash them.

I believe it's very nice because the trays before were very whimsy and they broke easily, and also the forks, the plastic forks also broke.

So, I liked the new metal forks better.

And I believe it's way better for the environment and also way cheaper for the school.

So, I believe it's all-around way better than the other trays.

This is Shalev Sabag from the Lahaina Intermediate School for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

[chime] Friends, I hope your transition back to school goes well and you find peace and healing together.

This next story comes from our archives.

Students from Lahainaluna High School explored Hale Pa‘i on the grounds of their campus.

It was once a printing press and now its museum contains a million Hawaiian language newspaper pages.

Welcome to Hale Pa‘i on the grounds of Lahainaluna High School.

My name is Ken Kimura, I'm with Lahaina Restoration Foundation, and I work here at the Hale Pa‘i printing Museum.

Hale Pa‘i started in 1834 with a grass shack, a grass hale, and we had one press, it was a press that was sent over from Honolulu.

We have a replica here in the building, but the original press no longer exists.

So, in 1837, three years later, they built this building, and it was used for printing.

We have about a million pages of Hawaiian newspapers that were printed.

Now of that million pages, we only have maybe 5% at most translated.

Just as the early Hawaiian papers recorded the news and culture of their time, Ka Leo o Maui is capturing our story for students today, and perhaps for students 100 years from now.

[chime] I think that effort to preserve history is beautiful, despite the press not being used anymore.

I'm happy to report Lahainaluna High School's football team came back to play a game against our school, H.P.

Baldwin High, just this month.

It gave us a sense of normalcy again.

Here's a quick report from my classmate, Kainalu Catugal, about the game.

[chime] Ever since the fires on August 8, Lahainaluna wasn't able to practice and train for football.

On September 30, Lahainaluna was able to have their first football game of the year.

With so much support from the island, the game was filled with so much cheering and love towards the Lahainaluna football team.

In the end, Lahainaluna won the first game of the season, beating Baldwin 42 to 0.

[chime] This next archive story shows that the kindness from an everyday job, like a crossing guard, can touch lives and affects so many people.

In 2014, the students of the Lahaina Intermediate School profiled Uncle Harold Kaniho, who worked as a crossing guard for King Kamehameha III Elementary School.

He passed away in 2019 according to Lahaina news.

Let's take a look back on his legacy.

For as long as many people can remember, Uncle Harold, the crossing guard for King Kamehameha III Elementary School in Lahaina, Maui has kept his community safe.

I came here in 1994, and I've been here ever since.

But I, I really I don't know.

I really love it here, I mean helping the children.

That's my motivation.

And the, the kids, I see children happy and smiling and want to come to school and all that, you know.

It really motivates me to keep on doing it.

I really like that.

Uncle Harold originally turned down the principal of King Kamehameha III Elementary when she offered him the job, but his granddaughters pressured him to take it.

I was so glad they told me to do that, but I was upset with them because they cut me off.

They said, “Oh, grandpa, I gotta do this.

You gotta help out.” And I never was so thankful for, for all those for that, for doing that, because it really made me aware of what I needed to do, really, to give back to the school, give back to the, to the community and stuff like that.

Now Uncle Harold finds it hard to miss school.

They just want to see me, they just want to give me high fives, they just want me to hug them, you know, and that's why it was so hard.

I cannot leave them just like, even we have family get togethers and on other islands, and stuff like that.

Normally I don't go because I’d rather, I don't want to miss school.

And my, my family gets angry.

Say, “Oh, you know, you gotta come and join us, this and that.” I say, “I’m happy doing what I'm doing.” A special gift that Uncle Harold brings to his job has caught the attention of many tourists who pass by the school as they explore Lahaina town.

I've had so many compliments, really, I mean I'm embarrassed by that.

I'm really embarrassed to say.

But they're very kind to me and everything.

They said, “We don't have this back where we come from, we don’t see people doing this.” They say, and they've taken a lot of pictures of me.

They’re, they returned back to the mainland, they sent me things and, you know, to school, because they don't want my address or whatever.

But their, their intention is to let everybody know if you want to see Hawai‘i, go to Maui.

Go to the island of Maui in Lahaina and go to that school.

And I've been having that kind of compliments for a long time.

I think I'm more blessed than more people with better jobs.

And I don't mind staying here another 20 years if God permits me to.

I'm 80 years old now.

You know, but I don't think I ever want to quit.

As long as I can move around and do something, I'd like to come back to the school.

This is Daisy Miranda from Lahaina Intermediate School reporting for HIKI NŌ.

According to the Hawai‘i State Department of Education, a temporary campus for the elementary schoolers at King Kamehameha III will be set up until a permanent campus is rebuilt.

This next story was produced by students at Maui Waena Intermediate School during a HIKI NŌ challenge.

The story is about a family farm called Hashimoto’s Kula Persimmons and Cherimoya.

Unfortunately, the trees you're about to see were severely damaged by the 80 mile per hour winds, ruining much of the crop just weeks before harvest, according to Honolulu Civil Beat.

The farm’s owners say they will have to wait until next season to see if their trees will survive.

We have this, the original trees that my ancestors, you know, planted here.

Located in Kula, Maui, Hawai‘i, Hashimoto Persimmon Farm has branched out into its fourth generation.

So, our farm is like 100, over 100 years old, my great great grandfather brought over the first persimmon tree from Japan.

Um, and then my great grandfather had this farm, then my, my grandfather, and now my dad, and my dad is running it.

And since I was born, I've been working on this farm, um, and now my children work on this farm.

Despite their busy schedules, it's in their roots to come back and help.

You know, during the season, which is really short - it's only from October to like, end of November - my parents are here every day.

But my family and I are here every Saturday and Sunday.

We give up our weekends and we spend, you know, all day together.

So, my dad has worked really hard at keeping up, you know, the traditions, keeping up with modern times.

Um, my mom has worked at diversifying the farm by making products, you know, so we don't just have fresh fruit anymore, but we have scones and jams and cookies.

What started as a hobby has blossomed into a unique and successful business.

I have tried persimmons, usually they're imported.

I haven't ever had persimmons from Hawai‘i before.

So, you know, they bring them in from Japan, usually, from, um, the continent.

So, it'll be exciting to have, um, persimmons from Hawai‘i.

Customers are so important because if you had no customers, you know, we wouldn't have anyone to sell to.

So, we do enjoy when people come and visit and you know, people I think enjoy because they come and they see that, oh, it's the same, same farm, same people.

Well, one thing is now we do take credit cards, that's huge.

We never did.

Um, we have a website.

Um, we still you know, we do mail orders.

So, we, we’re trying to keep up with the times.

It's very hard to have a family business.

It's a lot of work, but, um, you know, it's very worthwhile and it's, it's the legacy is what's important and family’s what's most important.

And these years of hard work have helped the farm and the family flourish.

This is Kallysta Miguel from Maui Waena Intermediate School for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

We wish the Hashimoto Family the best as they work to recover this special and historic orchard.

This next story was produced for HIKI NŌ by Lahaina Intermediate School students in 2012.

They decided to cover the restoration of their town's historic smokestack.

I remember visiting here when I was young and being amazed by the height of it.

Let's watch.

Lahaina Restoration Foundation has spent over $600,000 restoring a smokestack that does not work.

The Pioneer mill made an imprint on Maui and its people, so its closing in 1999 affected everyone.

It's a, it was a question of, uh, it wasn't making money.

Sugar was no longer making money because the cost of labor and, and everything, and just the cost of equipment was a lot more expensive in the United States than it is in other countries, so sugar is produced in other countries a lot cheaper than it was here.

The Pioneer Mill Smokestack is an important landmark in Lahaina.

But why save it?

The smokestack was in danger of being demolished, and the community wanted to save it.

And we thought it was important icon of the plantation era.

So, we saved it.

But every morning, there was a whistle, and the whistle would blow.

And basically, the whole town kind of lived their life on those two whistles, one that was at 6:30 in the morning, and one at 3:30 in the afternoon, and you can hear it all the way to Kā‘anapali.

This was like the centerpiece of, of the community.

So it was, was very important, and it was really a good thing that they, that they restored it.

Restoring the smokestack took considerable effort.

It was, uh, it was a pretty decrepit, uh, smokestack at the point that, uh, they're ready to knock it down.

And, uh, what the major problem was, it's 210 feet, but the last 20 feet were almost so crumbling, they were about ready to fall down.

The big crown, if you will, was starting to deteriorate, or started to what they call spall, all the, uh, cement was coming loose.

So, uh, that was the major part, they, uh, we immediately hacked the top off of it.

And that's where it sat for about, excuse me about two or three years, until they came back.

And if you look at the smokestack, you'll see bands around it.

They fortified the whole smokestack with bands that look like barrel staves around at certain points.

And, uh, they fortified that and then they completely rebuilt the top 15 feet.

And the crown itself is interesting because it used to be cement and segmentations material that they did in the earlier days, back when they built it.

And we said, and the Oak Park chimney guy said, “We have a better idea.

What we'll do is we'll bring a metal one, and we'll ship it over there in four parts, and then we'll weld it together and with a helicopter put on the top, and we'll paint it and nobody will know the difference.” And it's much stronger and much lighter, and cheaper.

So that's what we did.

The restoration was a costly process.

But the Foundation has found a way to restore their funds with the brick selling project.

What we do is we're selling bricks to the community, and they get their name, uh, engraved in the brick and, um, some other saying.

A lot of the mill workers who have one particular color, they write not only, um, their name, but they write their position at the mill and that, and the years that they work there.

So, it's become a real community testament to the whole plantation era.

This is Kyle Schultz reporting from Maui Waena Intermediate School for HIKI NŌ.

Now I'd like to end on a sweet note with this archive story from Maui High School students who profiled a family who came up with the awesome concept of having a food truck out of a Volkswagen van.

[chime] I would say for the fruit shaves, it's, uh, very similar to, uh, I would, I would say like cotton candy.

Because you think that you're going to need to chew it, and it throws your mind for a loop.

You think you're going to need to chew it, but it actually just dissolves right in your mouth.

It's amazing.

I highly recommend it.

A lot of people assume that, that my husband's name is Gus, so they'll refer to him as Gus.

But Gus is the name their four children gave their Volkswagen bus.

It was a one in a million chance they were able to get just the right ingredient to move their business forward.

Uh, it took me a few years, because there, there was a lot that you could find that are already refurbished or already ready to, you know, have everything inside and everything, and I didn't, I didn't need that.

And so, it took me a while to find the right one that, that actually said, hey, this one is, you can do a food truck out of this guy.

…Orange slices.. After countless hours of fine tuning and restoration, Gus’ Hawaiian Shave Ice opened on the south shore of Maui in Kihei in 2016, but they proved that Gus is no ordinary shaved ice truck.

We were talking about what we could open that unique that would add to the community that, you know, Maui doesn't have.

So, we thought well, what if we open a shave ice truck and put a different unique spin on the shave ice.

Hey guys, you want rainbow?

To get their unique flavors and texture, the Christopherson family uses fruit they grow on their own property and by supporting local farmers.

We try to keep it all locally sourced as much as we can.

By using fruit frozen in the blocks, the Christophersons don't need to add any sugar.

Would you like any sweet cream on top?

No.

We get a lot of people that are diabetic, because they don't have a lot of, uh, dessert options available to them.

And this gives them the dessert option because it doesn't have any of the sugar in it.

This sweet treat attracts locals as well as many tourists.

They told us last night that it was the highlight of their trip and then they laughed and they said, "Well, we did get married."

The icing on the cake for the Christophersons is about running a small business while also teaching their children life lessons.

I always wanted to teach our kids how to work in business and how to handle like, finances and customers and, and the prep and everything that goes into it.

We think that they'll be better, uh, prepared as they move out of our home.

You're getting dessert, you're getting a shave ice, you’re already in a good mood.

And then you’re getting it out of a bus, and it just makes it even better.

This is Alyson Kar from Maui High School for HIKI NŌ.

[chime] According to their Instagram page, Gus’ Shave Ice continues to spread cheer by providing shave ice to friends across the island.

Well, we've come to the end of our show.

Mahalo for watching our cherished memories of Maui and the work of Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

The students of Maui are strong, brilliant, and resilient, and we will continue to tell the stories of our people.

So, keep watching and please follow PBS Hawai‘i on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok.

You can find this HIKI NŌ episode and others at pbshawaii.org.

Tune in next week for more proof that Hawai‘i students HIKI NŌ, can do.

[outro music]

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i