10/31/23 | Unveiling the Science of Unlocking Innocence

Season 15 Episode 2 | 28m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

Student reporters explore cultural classrooms outdoors and online.

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, student reporters explore cultural classrooms outdoors and online, interview criminal justice experts, investigate the rollout of a new state law, and profile a Hawaiian hula teacher and cultural practitioner. EPISODE 1502

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i

10/31/23 | Unveiling the Science of Unlocking Innocence

Season 15 Episode 2 | 28m 11sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, student reporters explore cultural classrooms outdoors and online, interview criminal justice experts, investigate the rollout of a new state law, and profile a Hawaiian hula teacher and cultural practitioner. EPISODE 1502

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch HIKI NŌ

HIKI NŌ is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[intro music] HIKI NŌ, Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

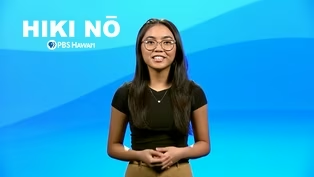

Aloha and welcome to this week’s episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

I'm Denise Cabrera, a senior at Wai‘anae High School on O‘ahu.

I'm delighted to be your host and to share the work of Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

In this episode, we'll learn how newly processed DNA evidence can change lives, including the life of one Hawai‘i man who was released this year after spending 25 years in prison.

We'll see how a remote school on Hawai‘i Island is sharing its campus with the world through 360-degree virtual tours, and visit a historic living classroom and Mānoa Valley.

We’ll also watch a special report from a HIKI NŌ alumna about the rollout of a new law requiring period products in public school bathrooms.

And we'll meet a kumu hula and Hawaiian Studies teacher who is passing on her legacy to students on Hawai‘i Island.

Let's start the show with a story from Highlands Intermediate School on O‘ahu.

Our student reporters there decided to take a closer look at how the legal team of the Hawai‘i Innocence Project is using the latest forensic science to exonerate prisoners who have been wrongfully convicted.

No one wants to see anybody in prison for a crime they didn't do.

When you think of prisons, the justice system as a whole, even, you think of the fairness of the law.

But nothing is perfect, and the justice system is no exception.

My name is Kenneth Lawson, I'm the Co-Director of the Hawai‘i Innocence Project.

Getting our, our case with Ian Schweitzer.

He spent 25 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit.

We freed him because of the DNA.

Ian Schweitzer was serving a life sentence when he was proven innocent and released in January of 2023.

His freedom was thanks to the new advancements in forensic science.

These advancements are changing many lives, not just Schweitzer’s.

Very small amounts of material can make a huge difference.

Like now, recovering a single hair at a crime scene can be a critical item of evidence to, to be studied, used, or analyzed using forensic methods.

Since 1993, since the Innocence Projects started throughout the United States, uh, over 300 people that had been locked up, have been free through DNA testing.

I think it's absolutely exciting and wonderful that they're exonerated.

When these things happen, my, my only frustration is how long this process takes because we knew, we knew for years that they were innocent, but it has to work its way through the whole criminal justice system.

Exonerees of wrongful convictions, even after gaining their freedom, face new challenges reentering society.

When the judge said, “Uncuff that man, he's free.” And they saw it on TV, and they saw him hugging his parents.

Everybody thinks that you know what, now he lives happily ever after.

But when you think about it, um, like I said, he's 51 years old, who's gonna hire him?

You know, is he trained to do, uh, jobs out there now that he's been in prison for 24, 25 years?

Besides Schweitzer, the Hawai‘i Innocence Project has successfully exonerated three other people in Hawai‘i since the nonprofit clinic began in 2005.

They continue to work on the cases of those who believe they've been wrongly convicted.

You know, I think that all of us are here on Earth, that our primary purpose and we're here to be of help to one another, right.

And if we can't help somebody, just don't hurt ʻem.

This is Emma Forges from Highlands Intermediate for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

Our next story takes us to the remote fishing village of Miloli‘i on Hawai‘i Island, where students at Kua O Ka Lā Public Charter School are working on sharing their beloved backyard with a global audience online.

Let's find out what it takes to build a virtual tour.

Located more than 30 miles south of Kona, Miloli‘i is Hawai‘i's last remaining fishing village.

It has a rich history.

Kua O Ka Lā Public Charter School students are now sharing the beauty and culture of their place through virtual tours like this one.

We live on a slope of an active volcano, Mauna Loa.

Behind me, you can see the lava flowed in this direction in 1926.

Along our coasts, Ho‘opuloa was one of the larger villages with a store, a post office, and a landing for trading ships.

The 1926 lava flow destroyed Ho‘opuloa as well as the bay.

Because many residents of Miloli‘i are descendants of those displaced Ho‘opuloa villagers, the whole region is now generally referred to as Miloli‘i.

A big part of our curriculum is also understanding our place.

Through virtual tours, we could connect our students’ projects like kilo, which is observing our environment, and connecting it to the place that we're learning, specifically here in Miloli‘i.

Students use cameras that capture 360-degree panoramas.

The images they take will become the visual elements for their own virtual tours.

Then they add clickable hotspots to create an immersive interactive experience.

I think a really like, interesting way of, um, to like, express your, like where you're from, and like, you can show other people.

It's just really cool.

Virtual tour enhances our students curriculum because they allow our students to share their voice, knowledge and stories of their place through a digitally innovative platform.

This project is a partnership with Arizona State University.

The ASU Center for Education through exploration is developing Tour It, an online platform that students use to create their tours.

The feedback from our collaborations and our use of it together is what has evolved the program itself to make it more user friendly and more accessible.

In addition to capturing images and videos, students must uncover the history, facts and stories behind these places.

My goal is that virtual tours will be a tool, but the creators will be the one who really make it fly by making the world be able to hear their stories.

Aloha I'm Kumu Pilimai and just here in Miloli‘i to talk about the Noni tree here, also known as the Indian mulberry tree.

Virtual tours are important to place-based learning because it allows our students to tell their story about the history, the mele, the mo‘olelo and the environmental significance of this place, this wahi that we care for.

Students get a deeper understanding of where they live and where they come from, preserve these stories, and share this richness with the world.

This is Ashley D'Ambrosio from Kua O Ka Lā Public Charter School for HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

Here on O‘ahu, there's an interesting historic property located in Mānoa Valley that often serves as a hub for cultural practitioners to share their knowledge.

McKinley High School student reporters take us there in this next story.

Tucked deep in Mānoa Valley, you'll find the Mānoa Heritage Center, an outdoor classroom with historical roots.

Jenny Engle, the Director of Education at Mānoa Heritage Center, says the nonprofit began when Sam and Mary Cooke wanted to inspire people to be thoughtful stewards of the community.

They are able to purchase this parcel, as well as the two parcels that create our lower campus today.

And so, it kind of begins this idea of creating Mānoa Heritage Center.

Founded in 1996, the Mānoa Heritage Center’s goal is to educate and inspire others on Hawai‘i's culture and natural heritage through schools and cultural practitioners.

- two sides.

We’re gonna end up putting them anyways, and then we're gonna end up stripping them into the appropriate sizes.

Included on the grounds is Kūali‘i, a century old home, as well as native Hawaiian Gardens, the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Visitor Education Hale, and Kūkaʻōʻō Heiau, a reconstructed ancient Hawaiian temple.

[Hawaiian chanting] We spoke with educators who experienced Mānoa Heritage Center during the teacher training hosted by the Office of Hawaiian Education.

This experience is just opening my eyes.

This, this area in Mānoa alone, it’s, it made me realize that the changes that, that our times is taking us through from almost losing an area like this, and somebody, somewhere, at some point in time, found it important enough to, to revitalize it and carry it through.

Getting to know your sense of place, because that can help guide your work, guide how you work with other people, guide the criteria for the things you do.

And so, to go back to wherever you call home, and start asking those same kinds of questions like, “What is the traditional place name of where I'm from, or where I live?” You know, just that small, giving yourself a small window every day, right, just to kind of observe your space, your place, right?

It's really transformative.

Mānoa Heritage Center inspires a sense of place to those who take the opportunity to discover.

From grounding yourself in the gardens, to strengthening your connection to Hawai‘iʻs cultural roots.

This is Gavin Simon from President William McKinley High School for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

[ocean wave] A year after Hawai‘i state officials passed a law requiring free menstrual products to be provided in public schools, Kaua‘i High School graduate and HIKI NŌ alumna Kate Nakamura wanted to follow up.

Her special report was produced in collaboration with PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs.

All the public places that we have access to as citizens, if there's toilet paper and soap stocked there, to me, there should also be period products stocked.

Not being able to afford menstrual products is known as period poverty.

It's an issue of inequity that is familiar to teachers like Sarah Kern, who witnessed the issue while teaching at Chiefess Kamakahelei Middle School.

I saw a lot of period poverty at our school.

It was, it was mostly indirect.

There were, there's a lot of students who would go to the health room to get their, their products and that resulted in missing class time.

Um, I personally, and a lot of teachers, would provide products to students so I would always keep some in my desk.

You know, when we talk about, for example, Hawai‘i Public Schools, um, because so many of our schools are Title I schools, the vast majority of our menstruators live in fairly high poverty communities and conditions.

It took several years of lobbying, but students and advocates celebrated a victory in June 2022, when legislation requiring the Hawai‘i Department of Education to provide free menstrual products in public and charter schools was signed by the governor.

Hawai‘i is now among nine states in the US to do so, according to the Alliance for period supplies.

It's already making a difference to students like Breanne Battulayan who attends Kaua‘i High School.

The first time I started seeing free period products in school was about a year ago, and my initial reaction was, “Wow, this is different and could help other girls and not just me.” The first time I saw it was in PE and I was like, oh my gosh, wait, I don't have to carry like, my like, big period bag everywhere.

I literally just have a pad right there that I can just grab from the wall.

Kern, who serves as the Kaua‘i representative for the Ma'i Movement in addition to teaching says expansion of access to free menstrual products in other spaces in the community, such as university campuses, will benefit local menstruators.

One of the next steps to getting period products more widely accessible throughout the state is definitely getting them, um, free and accessible in the U.H.

system, so, the community colleges, U.H.

West O‘ahu Mānoa, U.H.

Hilo, um, all of those campuses, it would be great if they provided period products for free, uh, to other students and, and faculty as well.

To push for further change, it will take diverse and new voices in legislative matters.

I think that the most difficult obstacle is the education piece, um, because sometimes, not always, but sometimes legislators live in their own bubbles, right?

So, and that can affect the quality of their policymaking.

So, if they are not actively seeking out young people and, and trying to, um, identify the concerns of young people and then working to address them, then they're never going to be engaging young people.

I'm Kate Nakamura for HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

Kate was one of the five students in the country awarded with the PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs 2023 Gwen Ifill Legacy Fellowship, providing her with special mentorship from the PBS Hawai‘i station for this story.

Let's hear from her about the experience.

Hi, my name is Kate Nakamura, and I was a 2023 Gwen Ifill fellow.

I was elated to have the opportunity to work with the PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs again.

Through working with them during my high school years, I learned a lot about the importance of student voice, and I became more aware of the issues that are present in the world around us.

I was also grateful to work with the amazing folks over at PBS Hawai‘i’s HIKI NŌ.

HIKI NŌ is an organization that I was able to work with from my sixth-grade year all the way up until my senior year.

Through working with them this summer, I was able to highlight a local issue that means a lot to me, which is period poverty.

I wanted to highlight the good that is being done and what needs to be done to keep the conversation going and the change flowing.

I was able to speak with local legislative and community leaders about their experiences and what they're doing to help chip away at period poverty here in Hawai‘i.

I was also able to speak with students who experienced this change and want to see more happen.

Overall, I learned a lot about asking the right questions, story structure, but what it means to be a storyteller in this day and age.

Mahalo, or thank you, to SRL and PBS Hawai‘i.

[ocean wave] Thanks, Kate.

We hope your journey at the Arizona State University's journalism school is off to a great start.

Now I want to turn to our archives to share a story about Logyn Lynn Puahala, a nine-year-old female judo champion.

This one takes me down memory lane.

My classmates and I produced it while we were students at Wai‘anae Intermediate School in 2019.

Logyn Lynn Puahala is a nine-year-old trying to make her way to the top in the sport of judo.

Her parents are part owners of Hawai‘i Kaikaku judo club located in Waipahu, Hawai‘i.

It is here that Logyn spends many hours each week helping to train preschoolers as well as students who are older than her.

It was good to teach them because they don't know like, everything about judo.

They keep on like, running around and they don't like, listen.

One judo student who looks up to Logyn as a role model is her best friend, Eli Oshiro.

She inspires me by helping me train for whenever I go up to the mainland.

I want him to learn some moves from me.

But who is the better of this duo?

She has more balance and ability to throw me.

Judo training is something Logyn is learning from her role model who is also her coach and her father, Robin Puahala, Jr. And you still have to turn your wrist.

Because he teaches me things.

He, um, coaches me at the tournament.

As the head coach for Pearl City High School, Coach Rob has won five state championships and has come in as a state runner up six times.

He has also been named the Hawai‘i High School Athletic Association's judo coach of the year five times.

After watching her father coach many championships, it's only natural for Logyn to want to be a champion herself.

I want to get to the Olympics and win.

She's not alone in her goal.

My goals for her are high.

I want her to go to the Olympics or World Championships.

Having her father as her coach can be challenging.

She's my daughter.

So, uh, you, I feel that I have to push her a lot harder than most people.

I don't give her a lot of slack that other kids get.

So, it makes it harder for me and harder for her.

It's that kind of coaching that is helping Logyn win championships.

She already has six national titles, three international titles and one bronze.

Uh, currently only one loss, I don't know how many victories.

The one loss is the only one that matters to us and the only thing that we really keep track of.

Keeping track of her loss is what Logyn and her father are using as motivation for her future tournaments.

Push her.

I need to push her day in and day out.

I get as much training as I can.

No matter what the future holds for Logyn, one thing is certain.

I just want the best for her.

Whether she succeeds or fails, I'm still there for her as a coach and as a father.

This is Denise Cabrera reporting for Junior Searider Television.

Our next story from the HIKI NŌ archives was produced by Sacred Hearts Academy students on O‘ahu.

They tell the story of their school's professional mentoring program, and follow one junior who landed an internship at Hawai‘i News Now.

It's called Girls Got Grit.

Let's watch.

When Shelby Mattos isn't busy studying, the Sacred Arts Academy junior is working hard at the TV news station Hawai‘i News Now.

She's part of a mentorship program called Girls Got Grit, which empowers students at the Academy to get a head start on becoming leaders in their communities.

Being in Girls Got Grit allows students to enter a professional business environment, and doing that kind of sets a level of expectations for when we enter the workforce.

And it also kind of builds us as businesswoman, and so I feel confident to sell myself and sell something in the future.

And so, I feel like that will help me in the long run.

Students get a taste of what it's like to pursue a career before they enter the workforce.

Others have interned at Castle Medical Center and Alexander and Baldwin.

They are partnered with mentors, prominent women in the community.

They learn about work ethics, about how to write up business proposals, grouping these girls with various companies in the community, and for them to intern at their place of work to see all the different facets and opportunities that that company provides.

As Vice President of Saks Fifth Avenue in Hawai‘i and mother of two Sacred Hearts Academy students, Mrs. Shelley Cramer says success all comes down to grit.

It has nothing to do with IQ.

It's about the passion, you have it within yourself to become great.

And so, I thought that that would be an amazing word to use.

Hence, Girls Got Grit.

I want these girls to come out strong, empowered, and feel that they have a network that they can touch.

So, after they graduate, if there's an opportunity to come home, they know who to connect with, and how to come back into the community.

Shelby's already putting these lessons to good use, applying the skills she learned at her internship to her activities at school.

My favorite part had to be working with news because I'm the news editor for our school’s newspaper, so that's kind of where I lie and my heart is, just talking with them and reading articles and just doing things that I loved kind of added the heart to it.

Shelby's among the first group of girls to kickstart the program.

She admits she was scared at first because she did not know what to expect.

I applied to Girls Got Grit because I wanted to do something fun and new, and I feel like Girls Got Grit was something no one's ever heard of.

And it was terrifying to sign up for it because the initial group had no idea what we were doing.

So, it was kind of fun to be the first group to do that.

Shelby says the program turned out to be one of the most valuable decisions of her high school career.

I could see myself working at Hawai‘i News Now because they do so many things, and they get to like, work with all the different departments.

And especially because the community here is so loving and caring.

And so, it was so nice to see that, and I think I would love to enter with that.

Shelby learned the true meaning of grit and passion and is now inspired to help other girls discover their grit.

I'm gonna pass down what I learned from GGG to the next group, and hopefully they'll be able to find as much passion as I have in the program.

And it's just such an amazing experience to be able to talk to these professionals and see what they think and what happens in their lives.

This is Mikayla Lancaster-Hoover from Sacred Hearts Academy for HIKI NŌ.

[ocean wave] Our final story comes from middle school students at Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy on Hawai‘i Island.

They profiled their Hawaiian Studies teacher and kumu hula who shares her cultural wisdom and the love of dance with the next generation.

[Hawaiian] First and foremost, what is the goal of what I teach and why I teach?

Um, number one, the sharing of aloha is really important.

That aloha is inclusive to all of us.

Aloha does not separate any of us.

Not many of my students come from or are born in Hawai‘i, but they find themselves here; they have a connection to this place.

And so, our job is to give a sense of belonging, give a sense of purpose, uh, give a sense of responsibility to the place that they live, and they thrive.

She's taught me a lot of stuff with Hawaiian culture and hula and how she's brought me up as well, giving me confidence.

When I was in college, my Portuguese family, um, would introduce me as Nicole, who was going to college who was going to be a teacher.

And, um, I actually did not want to be a teacher.

But my grandmother just kept saying, like, one day she's going to be a teacher.

We never know what's ahead of us.

And sometimes our kupuna can see a light within us that we don't see within ourselves.

One of my good friends from Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy came to me and said, “You know, HPA is looking for a Hawaiian Studies teacher, and would you be willing to, to apply?” With some hesitation, I said, “Okay, I'll give it a chance.” I did Hawaiian language for eighth grade, and then I also did, um, K5 Hawaiian studies.

Bringing hula to the school was another way of engaging students more deeply rather than watching video and or listening to lectures, but more engaging them in the physical of what it means to be engaged in the culture.

While performing my first ho‘ike with my hula hālau, I was scared.

Kumu Kuwalu put us in a circle, said a few encouraging words, and then we were onstage.

She helped me find my voice, and now I am more confident in myself.

I've had a student, her name is Healohamele Genovia, and I've had her since she was about second or third grade.

Uh ,we decided to do an ‘uniki ceremony, um, for Healohamele to graduate as a kumu hula.

And then it took a one year of intense training, um, of, of creating so that she has the skill, she has the confidence to continue and perpetuate what I've left behind.

Kumu Kuwalu in all her magic and aloha is a reminder for me about the kuleana we have as kumu hula to nurture each dancer's spirit.

Hula is really, really important in the sense of generations.

Uh, the word hālau actually means many breaths.

And so, the idea of a hālau actually means for it to continuously thrive and for it to continuously live.

And so, they become more of the seeds of this place, and they sprout even greater.

This is Khloe Nakagawa from Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy for HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

That concludes our show.

Thank you for watching the work of Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

Don't forget to subscribe to PBS Hawai‘i on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok.

You can find this HIKI NŌ episode and more at pbshawaii.org.

Tune in next week for more proof that Hawai‘i students HIKI NŌ, can do.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i