11/7/23 | Becoming Confident in My Own Skin

Season 15 Episode 3 | 27m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Journeys toward self-acceptance.

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, student reporters investigate the issue of erosion, explore a local bookshop that supports Maui libraries, teach viewers how to use a special typewriter and share journeys toward self-acceptance.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i

11/7/23 | Becoming Confident in My Own Skin

Season 15 Episode 3 | 27m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i, student reporters investigate the issue of erosion, explore a local bookshop that supports Maui libraries, teach viewers how to use a special typewriter and share journeys toward self-acceptance.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch HIKI NŌ

HIKI NŌ is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[intro music] HIKI NŌ, Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

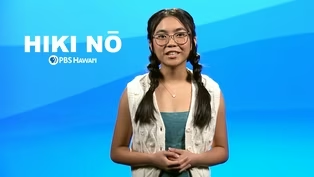

Aloha and welcome to this week’s episode of HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

I'm Denise Cabrera, and I am a senior at Wai‘anae High School on O‘ahu.

I'm here to share the work of Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers, and I'm excited to be your host.

In this episode, we'll watch a report from Highlands Intermediate School that includes a special interview with a woman who narrowly escaped a boulder that crashed into her home in Pālolo Valley on Oahu.

We’ll learn how to use a special typewriter for the visually impaired from students at Waikiki Elementary School, and we’ll meet a volunteer who runs a bookshop that supports local libraries on Maui from students at Maui Waena Intermediate School.

Our first piece comes from the students of Waikīkī Elementary School on Oahu.

Their classroom takes part in a program called Learning Labs, an activity based collaborative learning initiative.

They use a Braille typewriter to communicate with a classmate, and now they want to share what they've learned with you.

Have you ever wondered how people write in Braille?

People use Braille, a system of raised dots for people with blindness or low vision.

In our class at Waikīkī elementary school, we do Lucky Labs.

Lucky Labs are where we learn different strategies that help us understand the world from the eyes of people who are visually impaired.

We do Lucky Labs and we feel we're the luckiest class in our school.

We are the only class in the school with a visually impaired student that uses a white cane.

We're instructed by Ms. Amy who is a teacher of the visually impaired.

Braille was invented by Louis Braille in 1824 at the National Institute for Blind Children in Paris, France.

He spent years perfecting it.

Here's how to use a Braille writer.

First, write down the message you want to write in Braille so you don't forget it.

Then slide a piece of special thicker paper into the slot at the back of the Braille writer.

Spin both rollers on the sides of the Braille writer.

Look at the Braille chart to show you how to write individual letters.

Press the keys down at the same time for each letter.

Then when you finish the line, there's going to be a ding.

That means you've reached the end of the paper.

When you reach the end of the line, move the slider to the left and press line space again.

When you're done writing your message, pull the lever to release the paper and spin the rollers away from you until it stops.

Finally removed the paper from the Braille writer.

Congratulations.

Now you can share your message.

Now that you know how to use a Braille writer, next time you have the opportunity, you can try it.

The next suitor reflection comes from a student on Hawai‘i Island, this time from Ka‘u High School.

She tells a story of how she became more confident in her own skin.

Let's watch.

Hi, my name is Nyori Noelle Soriano, and I am a junior from Ka‘u High School on the Big Island of Hawai‘i.

I struggle with a skin condition called psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a skin condition under the umbrella of eczema types.

This caused my skin to flare out very badly and left patches on my skin.

I looked at myself like I was a monster, and this eventually caused my self-esteem to plummet.

I didn't look at myself like my peers looked at themselves.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, when I saw other people wearing their masks to protect themselves and others from the virus, I was wearing mine to hide myself from embarrassment.

But somewhere in the summer of 2023, I realized that other people struggle with self-confidence too, when my friends were telling me about their own insecurities that I never noticed in them, like the way they laughed or the way they walked.

I looked at myself from the point of view of others.

It didn't matter what I looked like at all.

If I didn't care what people look like, I shouldn't care about how I look like myself.

So, I took off the mask and gained confidence in my own body.

What I learned from this is that it doesn't matter how someone looks to you because on the inside, we're all human beings with our own insecurities.

It doesn't matter if you're different from someone else.

What matters is that you let others see your inner beauty.

If you're lacking confidence in yourself, just remember, a person's beauty is the quality of their own character, not their appearance.

[ocean wave] HIKI NŌ student reporter Isabella Seaman, an eighth grader at Highlands Intermediate School, got an interview scoop with a Pālolo Valley resident whose home and life was rattled by sudden rockslide.

Here's her story.

[crashes] When the glass shattered, I kind of stepped back and I, I didn't know what happened initially.

I'm here in the Pālolo Valley neighborhood where Caroline Sasaki had her home hit by a 3,000-pound boulder on January 28, 2023, at around 11 p.m. She says it was scary and shocking, but it hasn't necessarily been a surprise to her community, which has been voicing concern about loose boulders for years.

We were upset even before this happened.

Um, our situation, I've had neighbors who've contacted, um, councilmen, um, representatives, senators, um, to, you know, look into the situation.

It's been ongoing for many years, um, that the boulders are getting loose and, um, starting to fall.

There's other, you know, other situations where boulders have come down.

There was a landslide on the North shore where the rocks are falling and it closed the road.

Um, so, it's an issue that needs to be addressed by, you know, all parties that are involved.

We reached out to Honolulu City Council Member Calvin Say, who represents the district that includes Pālolo Valley, to find out more about the problem.

He says erosion is a growing issue in many communities.

The weather conditions, climate change, the stormy rains that we have, the persistent wind that we have, all of this may have contributed or have contributed to the erosion surrounding that big boulder.

It's also the fact that sometimes in a natural disaster, they have a word they call acta jure, meaning Act of God.

It could, if it's the Act of God, it's very hard to have any form of litigation, because you will never know if your property will be held accountable or liable for a boulder that through one's home.

Councilmember Say says he has heard from many of his constituents about the issue, and the county government is looking into possible solutions.

We have contractors that the state and the county has hired to maintain those boulders where they are at, but it is because you have wire fencing.

Wire fencing, not meaning wire fencing that you just put up vertically, no.

These wire fencing will be at the bottom or at the tip of where the boulder is close to the ground.

What I would like to see is that maybe in the future, and I apologize to other private landowners that there is no more development on the sides of these mountains.

I think maybe we should have a drone to map out, you know, are there boulders in our property that we had, versus the other side of the property line that other private owners are.

Natural disasters like these pose not only physical harm, but long term mental and emotional harm on people, too.

Sasaki says she hopes her story will inspire others to prepare for the unthinkable.

People have asked me if I have PTSD or stuff like that.

Um, at this point, no, but who knows, you know, it could affect people later.

All my life, basically 65 years, and it's never happened.

But now talking to other people, I found out that it has happened.

It's just not newsworthy because there was no video.

Luckily, we had a video that shows exactly what can happen.

Building fencing and using drones to identify potentially risky boulders will likely take some time.

For now, we can spread awareness to the people of Hawai‘i.

This is Bella Seaman from Highlands Intermediate for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

Thanks, Bella, for that eye opening report.

Now let's travel to Maui.

Our next story comes from Maui Waena Intermediate School students who interviewed a longtime volunteer with the Maui Friends of the Library, a nonprofit that helps to keep libraries open.

It's a huge community service.

Let's find out more.

100% of the money that comes across every counter goes directly to the libraries.

Rick Woodford, the Treasurer at Maui Friends of the Library, lends a helping hand to libraries around Maui.

I decided to be a volunteer because I used to shop at the stores, and I love books.

So being a volunteer gives me the opportunity to see people when they bring in the books that they donate, and I get to look through the boxes first.

So, I get to find treasures that I really like.

The organization’s basic mission is to support the libraries of Maui County.

Maui Friends of the Library open stores that sell books that have been donated to give money back to libraries so that they can purchase new materials.

Anything that the libraries need that they can't get in their own budget from the state we cover for them.

We are 100% volunteers.

There's nobody in our organization that gets a dime.

We operate three bookstores on Maui.

We this year are giving $10,000 to each library on Maui.

I think that every community should have a library.

It, uh, gives an opportunity for people of all ages from young kids to grownups to learn about books and to experience how much books can provide.

The importance of books in everyone's life is what made them want to assist.

This is Kingston Cabreros from Maui Waena Intermediate School reporting for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

Let's take a moment to visit the HIKI NŌ archives and learn how to make a special kind of shell necklace from the students of Island School on Kaua‘i.

People in Hawai‘i are very talented at making jewelry with things they find in nature, like this puka shell bracelet, which is made from a type of shell found on our beaches.

Puka is Hawaiian for hole.

The puka shells start off as cone shells in the ocean.

Tumbling in the surf and sand cracks the cone shell and separates the tip from the bottom.

Further wave action smooths and polishes the edges.

Today we will be showing you how to make a bracelet out of them.

To make the bracelet you will need puka shells, fishing line, a needle, and the scissors.

Start off by taking your puka shells and poking the sand out within a needle.

Lay out your puka shells before stringing.

Have the biggest one start at the middle and the smaller ones on the ends.

Measure your wrist with a suji and cut it with scissors.

You might need a friend to help you with this.

Finally, string the shells on and tie a knot to secure it.

And there you have it, your very own puka shell bracelet.

This is Amber Asuncion from Island School for HIKI NŌ.

[ocean wave] This next story was produced by students who participated in the summer school program at Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy on Hawai‘i Island.

They take us to Ulu Mau Puanui, an outdoor classroom where visitors learn about some of the traditional Hawaiian methods of farming, one of which relies only on the rain.

I would love for you guys, the next generation to be comfortable on the land.

On the Island of Hawai‘i, north of Waimea, a local teacher has been working to preserve Hawaiian traditional farming methods and also seeks to share this mindset with the next generation.

My profession is about sharing what I learned I think from the land, and the thing that I enjoy the most is when you guys come.

I get more, um, hands to help with the work and I like to learn from you guys too.

Kumu Marshall began her journey, unaware of the specific cultural practices pertaining to sustainable farming, specifically farming dryland crops with just one water source, the rain.

Now, Kumu Marshall works for Ulu Mau Puanui, a nonprofit organization focused on the research and understanding of Hawaiian rain fed farming methods.

When I first started working here, I did not know about this part of my history.

And I came from a background of teaching, and I was teaching in a culturally grounded school.

Um, and I did not know this piece of my culture.

So, when I learned about it, I thought okay, here's a kuleana I think I need to take on and share with more people.

At its peak, this farmland was 25 square miles, which is around 11,000 football fields in size.

Over many generations, the people learned to grow crops such as soup, potatoes and sugar cane.

Farming the land was challenging, but this rain-fed farmland fed upwards of 130,000 Hawaiians prior to European contact in the late 1700s.

Students who visit Ulu Mau Puanui get a hands-on education through working and engaging with the Hawaiian culture with unique farming practices and growing plants like the past generations.

It was hard to climb up, but the scenery was so beautiful, and also fun to learn about Hawaiian language.

What I got from this experience was an expanded knowledge and connection to my Hawaiian roots.

We learned about the methods passed down from our ancestors.

It was both eye opening and inspired me to take a more sustainable path similar to Ulu Mau Puanui’s.

Through her work, Kumu Kehau seeks to help future generations to connect to the land.

And I wanted to, I want you guys to understand it's a privilege and that, um, it's a, a matter of reciprocity where you give and you get, and you get and you give, it's a give and take.

Um, and I want it to just to be natural for you guys.

I don't want it to be a job for you guys.

This is Lorenza Torres Mayoral from Summer at HPA for HIKI NŌ on PBS Hawai‘i.

[ocean wave] Did you know that there are an estimated 50,000 Okinawans living in Hawai‘i, or approximately 3% of our population?

In our next story, students from Waiakea High School on Hawai‘i Island explore an annual summer camp for kids, where Okinawan culture and tradition run deep.

Let's watch.

Each summer for the past two decades, kids ages eight to 13 gathered in Hilo for a five-day camp where they learned to cook, drum, dance, and kick Okinawan style.

The theme of the camp is Warabi Ashibi, which means children at play.

So, my job is to make sure that they have a good time while they're learning a little bit about the Okinawan culture, as well as the plantation days activities.

In the 1900s about 25,000 Okinawans came to Hawai‘i and worked as laborers in sugar and pineapple plantations.

Being transported far from their native home, they brought their culture and tradition.

These traditions have carried through the generations, but some of these practices have faded over time.

This camp is very important because it perpetuates the Okinawan culture and it shares with the new generation of children like, what we used to do back in the old days, you know, when their grandparents first came here, or, um, things that kids their age used to do before there were any electronic devices or social media.

And I think that that's important so that they understand that not everything comes from technology, like they can still have fun even without it.

The camp includes special days like a field trip to Lili‘uokalani Gardens to play plantation games like tug of war, and a two person geta, or slipper race, picnic with their classmates, and have a fishing contest with different categories.

They also include a fun night where the kids make ube ice cream, and race miniature boats that they make themselves with the tournament amongst the classes to see who has the fastest boat.

The last event of the night is the hanafuda tournament where kids learn how to match and strategize a card game to get the most amount of points.

The camp left such an impression on Megan Escalona that she returned to work as camp staff.

As a student it was really, um, interesting to learn about the Okinawan culture, and to see the students now learning the same things I've learned in camp is really exciting.

On the fifth and final day, they showcase what they learned by performing their taiko, karate, dancing, and singing skills to their family and friends, where they're heavily applauded for their effort.

We have a really rich environment here in terms of culture.

And it's through appreciation of each other's culture that I think makes for a better world and for better understanding of, um, of people and sharing of quote “the aloha spirit” is what we want to say.

I think that's the main thing that we want to emphasize here.

This is Jessie Higa from Waiākea High School for HIKI NŌ, on PBS Hawai‘i.

Our next piece is also from the archives and has a special place in my heart since it was the first story I produced for HIKI NŌ when I was a student at Wai‘anae Intermediate School.

In it you'll meet a dedicated Judo instructor who teaches values of service and giving back all through the traditional Japanese martial art.

One of my proudest accomplishments was, um, winning the collegiate nationals to go on to the World University Games in, um, in judo at San Jose State University.

Uh, I first started judo when I was seven years old.

My dad told me to do judo at this club, Leeward Judo Club, so that is why I got started.

Judo instructor Matthew Ogata has been doing judo for 21 years and got his start at Leeward Judo Club which is in Pearl City on the island of O‘ahu.

I like judo because, uh, judo has done so much for me, the sense of ongaeshi.

And Hawaiian it's kuleana.

In Japanese, it translates to ongaeshi.

It means to give back, and to give back means to serve others, to serve the next generation, to help people with a servant's heart.

Giving back has always meant something to Matt.

That's why he went back to Leeward Judo Club to teach future Judoka.

The senseis, the teachers before me, have given me so much.

They've, they took a lot of their time to teach me judo.

So now, I think it's my turn for the next generation to pass it down and also help the next generation and um, using that term ongaeshi.

I first met Matt when I was about 13 years old.

He started training me for our first competition, or big competition that we did, junior national competition here in Hawai‘i.

He's, um, he's one of the reasons why I was able to continue through Judo without being so afraid of it.

He kind of showed me a different way to look at how Judo is played.

Matt wouldn't have gotten his skills in teaching if it wasn't for his own mentor, 1988 Olympic silver medalist, Kevin Asano.

He's, he has been my mentor since I started judo from seven years old and he's been with me, yeah, every step of my life and has helped me so much in ways that I can never be more grateful for and appreciate.

As a, an instructor, he's very careful to want to make sure that the kids right rise to a, a level of excellence, and so he pushes them to give their best.

The torch of leading Leeward judo club has been passed down from one generation to the next.

And now I see the next generation, uh, Matt, continuing on and that makes me very proud and happy.

I really appreciate, uh, Leeward Judo Club and our head sensei, Kevin Asano, for all he's done because he is the example of what a true, what true ongaeshi means, by really supporting other people outside of his family and also making it into a kuleana as well.

This is Denise Cabrera from Wai‘anae Intermediate School for HIKI NŌ.

Next up is a story from our archives.

It's a profile of an impressive kalo farmer on Kaua‘i produced by students at Kapa‘a Middle School.

Kinichi Ishikawa was 98 years old at the time of his interview with our HIKI NŌ student reporters.

Even if it rains, I still work eight hours a day.

So, I am good at my age at 98.

At 98 years old, Mr. Kinichi Ishikawa spends his days loving and caring for the taro fields on Kaua‘i’s north shore.

I was just a plain farmer, so working eight hours a day, and until now, I haven’t changed too much.

For Mr. Ishikawa, farming isn't just a job.

It's a lifelong passion and a longtime home.

He's been providing for himself and others on Wai Koko farm since he was a boy.

I’ve been living all by myself, right since I was 14 years old.

I never depended on anybody.

I did everything on my own to make a living.

Mr. Ishikawa’s agricultural knowledge and nurturing character greatly influences those around him, including the farm’s owners.

He has taught me how to cook taro his way, which is by boiling it a long time all day.

He has taught me how to pull taro.

He's taught me how to read taro patches.

He has taught me how to open a jabong with a sharp knife.

Mr. Ishikawa took a break from farming to serve in the 442nd battalion during World War II, but he eventually returned to Hanalei and his love of agriculture.

That love endured through the decades even as his hometown transformed with an influx of development and technology.

Most of the companies that hire all the educated people more than, more than just the high school graduates.

In my case, I just went to grammar school.

That’s all.

I never went to high school.

Despite a lack of formal education, Mr. Ishikawa stays true to the values and lessons cultivated from life on the farm.

He's taught me about long term planning on the decisions that I make today don't just impact what happens tomorrow, but it impacts a week from now and a year from now and 20 years from now.

And, um, I always feel like when I'm around Kinichi, I always leave enriched and I always leave with more than I came.

Family always comes first.

Family is most important, and hard work is good for you and will make you live longer.

Humble and hardworking, Mr. Ishikawa says he'll continue to care for the land and the people around him, no matter what.

See the branch is facing that way, so you’ve got to, you have to pull it away from the branch.

This one is fresh.

Thank you.

This is Ella Beck from Kapa‘a Middle School, for HIKI NŌ.

[ocean wave] According to the Garden Now newspaper, Mr. Ishikawa passed away in 2021, but his memory and legacy will live on forever, thanks to that special story our students captured.

That concludes our show.

Thank you for watching the work of Hawai‘i's New Wave of Storytellers.

Don't forget to subscribe to PBS Hawai‘i on YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok.

You can find this HIKI NŌ episode and more at pbshawaii.org.

Tune in next week for more proof that Hawaii students HIKI NŌ, can do.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

HIKI NŌ is a local public television program presented by PBS Hawai'i