VPM News Focal Point

Accessibility for All | March 7, 2024

Season 3 Episode 3 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

We examine how Virginia supports people with disabilities.

How does Virginia support people with disabilities? We examine accessible public transportation and new assistive technology. Meet students from the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind and a man with paraplegia who is getting his dream house.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown

VPM News Focal Point

Accessibility for All | March 7, 2024

Season 3 Episode 3 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

How does Virginia support people with disabilities? We examine accessible public transportation and new assistive technology. Meet students from the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind and a man with paraplegia who is getting his dream house.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: What's it like to be a Virginian living with a disability?

How easily can you travel where you need to go or receive a quality education?

Straight ahead, a school for the deaf and the blind, and technology that makes communication more accessible, plus a man using his best abilities to help those with disabilities.

VPM News Focal Point begins now.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪ ANGIE MILES: Welcome to VPM News Focal Point, I'm Angie Miles.

This episode is all about accessibility, examining problems and possibilities for those who live with disabilities, whether using assistive devices or adapting to life with a brain injury, teaching those who are deaf or blind, or working through physical limitations to support others who need help.

For people with mobility challenges, one of the most significant obstacles is transportation.

Multimedia Reporter Billy Shields shows us some common frustrations of just getting across town.

(bus beeping) BILLY SHIELDS: Wayde Fleming is a regular user of Richmond's bus system.

He takes the bus every day, and because he has arthritis, he walks with a cane.

It's something that has its own challenges.

WAYDE FLEMING: Crossing the street for one thing is challenging and it's hard for you to step up because sometimes they'll be in the middle of the street, they don't pull to the curb, and you stand in the middle of the street and you had to, you know, step up to get on the bus.

It's hard for somebody with a cane or a walker.

BILLY SHIELDS: Fleming is well aware of another challenge, what transit advocates call First Mile/Last Mile, which refers to the distance a bus passenger has to walk to get to the bus or from the bus to their destination.

STEPHANIE POWER: If you drive a car all the time, you don't have the same perspective as someone who's a transit rider.

I'm a bus rider as well as a biker.

So it's literally simple things like sidewalks that are even, that have a ramp in order to get on them, such that if a person's in a wheelchair, they have an easy way to move to the street.

(signal dings) AUTOMATED VOICE: Stop requested.

BILLY SHIELDS: Users of Richmond's bus system also point out that in addition to uneven sidewalks, there are not as many bus huts as there should be.

Something Fleming dealt with recently as he waited on a connection.

WAYDE FLEMING: Some stops don't have no seating, no place where you can stand at in the rain or snow.

BILLY SHIELDS: All of the buses have adjustable ramps to help passengers board, but Fleming says not every driver uses them.

WAYDE FLEMING: The bus driver should automatic let the ramp down, so handicapped people get off and on the bus, they shouldn't have to ask.

BILLY SHIELDS: After Fleming runs an errand at the hardware store, he'll have a two-bus connection to get back to his home on the edge of town.

ANGIE MILES: The Greater Richmond Transit Company told VPM in an email that it plans to improve bus driver training, and it's in the process of installing more bus shelters along its routes.

ANGIE MILES: When Focal Point asked people of Virginia whether society does enough for those who live with disabilities, we heard from a woman who says it's tough for people like her who need accommodations.

Is there enough support?

ELSIE TAYLOR: No, you're not.

And the reason why I say that, because we don't have enough access to wheelchairs when you riding in the stores.

And we need them badly 'cause we have too many people, especially military or civilians, they can't get into the stores because of that.

SANDY JONES: My heart goes out to those that are veterans that are disabled more than any.

And I always think we can do more.

DIANE POMART: I believe people have all kinds of disabilities.

Some are workable, some aren't.

But people who have disabilities, even though they can do certain things.

Sometimes they're depressed, they have anxiety, stress, but they can't really go into the work field and do the job the way they're supposed to.

NATALIE HUVANE: I know my friend works in the school systems, and she deals with most people that have disabilities and she helps them conquer anything in the school system that helps them, you know, feel like they're just part of everyone else.

MATTEO HIREL: I'm not sure if we do enough to help them with the issues that they face, both mentally and physically.

SELENA HUBBARD: I feel like a lot of people don't have enough heart because they feel like if somebody else is already helping them and catering them, why should I have to?

ANGIE MILES: When we focus on the needs of individuals with communication challenges, the hope increasingly points towards technology.

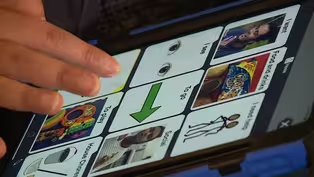

For people who are on the autism spectrum, images, when merged with technology, can unlock new ways of communicating.

Our special correspondent, A.J.

Nwoko connects us with affected families and experts who say that technology is helping neurodivergent individuals to reach their highest potential.

(Slinky rattling) (Daanish vocalizing) A.J.

NWOKO: Though 23-year-old Daanish Ali is largely non-verbal, (Daanish vocalizing) he has a lot to say, (Daanish vocalizing) and over the past decade, he's been able to convey more of what's on his mind.

DILSHAD ALI: You want to ask me for what you wanted?

A.J.

NWOKO: This is his voice.

(Daanish vocalizes) DILSHAD ALI: What are we looking for?

A.J.

NWOKO: But this iPad.

DILSHAD ALI: Okay, but can you gimme a full sentence, please?

A.J.

NWOKO: Is one of the main ways Daanish communicates.

COMPUTER VOICE: To go.

My bedroom.

DILSHAD ALI: Okay.

A.J.

NWOKO: It's called Augmentative and Alternative Communication, or AAC.

DILSHAD ALI: From like third grade onwards, it was a part of his life.

A.J.

NWOKO: His mother Dilshad Ali says these customized icons on Daanish's device are simple by design.

DILSHAD ALI: It's not used, you know, enough to be able to, like, say hi and hello to people.

A.J.

NWOKO: But it's become a difference-maker, because it takes some of the guesswork out of what Daanish is trying to say.

(Xena laughs) Xena Hernandez is beginning that journey with her 6-year-old.

XENA HERNANDEZ: He says a lot without saying too much.

A.J.

NWOKO: Xena says her son, Nico.

COMPUTER VOICE: I like to eat pizza.

XENA HERNANDEZ: Good job.

A.J.

NWOKO: Was diagnosed with autism just before he turned two.

By age four, he graduated from educational tools like picture boards to just about anything with a screen, like his AAC device.

XENA HERNANDEZ: Up until that point, he never answered a question before.

A.J.

NWOKO: Then Xena witnessed a breakthrough.

XENA HERNANDEZ: I said, 'What color is this?'

I pointed to something that was green, and he went and he hit green on his AAC device.

It makes me emotional, 'cause, up until that point, I was just.

That was honestly the first moment where I really had a sense of like, all right, what I'm doing is working.

A.J.

NWOKO: Whether it's an iPad, a learning board, or anything else in between, researchers say these technologies are designed to hone in on the skills and strengths of those on the spectrum.

ALISSA BROOKE: We don't focus on deficits other than what can we implement to support you so that we can reduce or eliminate what those barriers are.

A.J.

NWOKO: Melanie Derry and Alissa Brooke at VCU'S Rehabilitation Research and Training Center say success for those with autism comes down to access.

MELANIE DERRY: And the good news is that there's a huge push from the Department of Education to provide a lot of training around assistive technology so that we understand that it is both the supports, these items and tools, but also the services that we're providing individuals to use these tools.

A.J.

NWOKO: Brooke says sometimes the best tools can be found right in our pockets.

ALISSA BROOKE: And so simple things that already exist on the phone have been extremely helpful.

Alarms, and that can be in terms of getting ready for work so that you set your day up well.

A.J.

NWOKO: The researchers say technological advancements are opening up unexpected opportunities for those on the spectrum in school and in the workforce.

That uncharted territory captured the eclectic mind of Ellie Bavuso.

ELLIE BAVUSO: I do both virtual reality research and artificial intelligence research, specifically focused around neurodivergent accessibility in higher education.

A.J.

NWOKO: The VCU senior is also on the spectrum and wants others like her to be better at handling uncomfortable situations in higher education.

With the help of a personalized headset and software like ChatGPT, she believes trial and error in the virtual worlds she's designing can translate into success in the real world.

ELLIE BAVUSO: Even people with high access needs can still be independent if they have their accommodation needs met.

MELANIE DERRY: My big push would be early intervention and getting devices and supports in the hands of students that are in preschool, so that they don't have to wait until they come to school to begin learning how to communicate effectively.

XENA HERNANDEZ: It doesn't matter how they communicate.

What's important is that they're able to communicate.

DILSHAD ALI: We all need to be doing it in all environments to be able to maintain the usage of it.

COMPUTER VOICE: I want to eat.

A.J.

NWOKO: For VPM News, I'm A.J.

Nwoko.

ANGIE MILES: AAC devices equipped with the necessary software can cost well over $1,000.

There are nonprofits such as Lilly's Voice with a mission to help families in need with purchasing and learning to use the technology.

ANGIE MILES: VPM News Focal Point is interested in the points of view of Virginians.

To hear more from your Virginia neighbors, and to share your own thoughts and story ideas, find us online at vpm.org/focalpoint.

ANGIE MILES: Nestled in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley in Staunton, the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind, known as VSDB, is the nation's first school to serve both deaf and blind students.

All programs and services are free to residents from across the Commonwealth, and it's a hub of expertise that introduces students to technology and life skills to set them up for success.

For many, attending the school is a life-changing experience.

Senior Producer Roberta Oster takes us inside a place that has been building community for nearly 200 years.

ANGIE MILES: Kayla, Carina, and Morris continue to do well in both academics and sports.

All students at the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind receive special ed services through their individualized education programs.

This allows them to attend the school until they turn 21.

In part two of this story, we discover how VSDB prepares students for their lives beyond high school.

You'll find that segment on our website at vpm.org/focalpoint.

ANGIE MILES: Nearly 1.5 million Americans sustain a traumatic brain injury or TBI each year.

Often the effects of a TBI are invisible to the naked eye, but can be debilitating.

Joining us now is John Norment, a Harrisonburg resident who is a husband, a father, and was a third grade teacher before a severe illness caused a traumatic brain injury in 2016.

Thank you for joining us, John.

JOHN NORMENT: Thank you for having me.

ANGIE MILES: John, would you mind explaining to us, please, how did you end up with a traumatic brain injury?

JOHN NORMENT: I contracted a viral infection, not too dissimilar from the flu, but the virus ended up attacking my heart pretty aggressively.

So much so that I went from being perfectly healthy to suffering complete heart failure in a few days.

And when your heart fails, that causes clots to form the bloodstream, which cause several large strokes to occur, the largest of which affected my right hemisphere, basically destroying 80% of my right hemisphere.

ANGIE MILES: What were the side effects of that experience and how did they change your experience of life moving forward?

JOHN NORMENT: I had to relearn how to walk again.

I had to relearn how to talk again, I had to relearn how to read and write.

It also affected the optical nerves, so like I had lost all peripheral vision to my left.

To sum it all up, there was nothing I did not have to relearn how to do.

ANGIE MILES: So, when we are talking about people dealing with disabilities, some are more apparent, right, to the general public than others.

When people look at you, are there any giveaways?

Are there any signs that will tell them, this is a person who's dealing with a disability?

JOHN NORMENT: A comparison that I give when I talk about this, it's like everyone else is walking on smooth pavement, under a clear blue sky, and I'm wading through waist deep mud, with thick fog all around me.

I can get to where everyone else is going, but the amount of effort required is like astronomical.

ANGIE MILES: What is it that you think is necessary for people to receive the consideration and the accommodations that are needed in the work world and just in everyday life?

JOHN NORMENT: I currently sit on the board of a local agency called Brain Injury Connection in the Shenandoah Valley, and we have case managers that work with our clients to provide whatever adaptive technology that they need, like a case manager from an agency like Brain Injury Connections in their life to help them find the resources that they need to meet their goals, that will help out a lot.

(upbeat music) ANGIE MILES: You can watch the full interview on our website.

ANGIE MILES: This next story is about the gift of giving and one man who has given a great deal to others.

His generosity has been so inspiring that his community has decided that it's time to give back to him.

News Producer Adrienne McGibbon brings us this story.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: Justin Spurlock loves cars.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: I've just been around cars all my life.

I guess it's a guy thing.

My hobbies are just fishing and being around a lot of racing.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: His passion runs so deep that not even a life changing accident could change his mind.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: Yeah, it's kind of like a bike, you know?

You fall off it, get back on it and go again.

It's a traumatic experience, but you got to just keep going.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: He fell asleep at the wheel and woke up paralyzed from his chest down.

It took years to relearn how to manage everyday tasks and how to get around.

But once he got going, he had an insatiable drive to help others.

Justin heard about a teenager named Cole with a spinal cord injury, and he reached out to offer his help.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: I sat down with his dad that day.

He's like, "All right, let's make it happen."

That first show was my first car show I had put on, and we registered 400 cars that day.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: The proceeds from Justin's first car show helped pay for an adaptive vehicle for Cole.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: And that turned out real, real good.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: It was so good that Justin decided to do it again for another person with a spinal cord injury.

And then another.

Next, Justin started raising money for paralyzed veterans.

In total, Justin estimates he's raised over $150,000 for others.

He says, growing up, his grandparents taught him to always give a helping hand.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: So they were always like, You know, you work for what you get.

You know, you do right by people.

You don't see race.

You don't see, you know, sex or anything like that.

You just be a good person and just help them out.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: And now, after all that giving, it's Justin's turn to be the recipient of generosity.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: Thanks, bro.

KEVIN ENGEL: You can read over his resume and see how hard he has worked to help others and to do good work for the community.

And why would you not want to help a person that worked so hard to help others?

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: Kevin Engel has known Justin most of his life.

As a teen, Justin coached his son in roller hockey.

KEVIN ENGEL: We had to work for a good while to get him to agree to let us find a way to let others give back to him.

He lived with his grandparents, and he wants to be independent.

And with that spirit of not having any limits, he should have his own home.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: So that's how Justin ended up throwing a car show for himself, helping to raise money to build his dream home.

JUSTIN SPURLOCK: It's a different feeling knowing that what I've done for other people, and now the favor is being returned back to me.

The hardest part was accepting it.

And even till this day, it's an uncomfortable feeling, but it's a good feeling.

And if you want to grow, you have to be uncomfortable.

(cement mix whooshing) ADRIENNE McGIBBON: With donations and help from volunteers, construction has already begun on Justin's future home.

It'll be built to his needs and, of course, will include a massive garage.

Engel hopes it'll be the start of the next chapter for Justin.

KEVIN ENGEL: And certainly put him in a better position to do even greater things as far as being able to give back.

ANGIE MILES: Justin Spurlock owns his own company, creating graphic designs for vehicle wraps, and he's scheduled to move into his new home by the end of the year.

With innovative technology and the efforts of people like those featured in this program, we move closer to achieving greater accessibility for all.

To watch or share these stories, including the full interview with John Norment and our digital extra about the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind, visit our website, vpm.org/focalpoint.

You can also give us your feedback and story ideas there as well.

Thank you for being with us, we'll see you next time.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪

Deaf and blind students learning to live independently

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 7m 13s | A school for deaf and blind students takes building life skills seriously. (7m 13s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 3m 28s | A community is giving back to a man, who has given much to help others with disabilities. (3m 28s)

Innovations for Neurodivergent Minds

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 5m 45s | New technology is helping people with neurodevelopmental challenges connect with others. (5m 45s)

A nearly 200-year-old haven for deaf and blind students

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 7m 37s | Visit a school that’s been a haven for deaf and blind students for nearly two centuries. (7m 37s)

Real life impacts of an invisible disability

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 7m 2s | A traumatic brain injury survivor shares his experience of living with a disability. (7m 2s)

Wayde Fleming uses the bus from Fulton

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 1m 53s | Transit advocates are pushing for better accommodations for users with mobility needs. (1m 53s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown