Teachers, parents weigh benefits and risks of AI in schools

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 13m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Teachers and parents weigh benefits and risks of artificial intelligence in schools

Artificial intelligence is rapidly being integrated into many facets of life, including in America’s classrooms. As more school districts integrate AI into learning, we hear from parents and teachers grappling with the use of the technology in the classroom, and Stephanie Sy discusses more with Justin Reich, author of "Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education."

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...

Teachers, parents weigh benefits and risks of AI in schools

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 13m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Artificial intelligence is rapidly being integrated into many facets of life, including in America’s classrooms. As more school districts integrate AI into learning, we hear from parents and teachers grappling with the use of the technology in the classroom, and Stephanie Sy discusses more with Justin Reich, author of "Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education."

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS News Hour

PBS News Hour is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAMNA NAWAZ: Artificial intelligence is rapidly being integrated into many facets of life, including in America's classrooms.

As more school districts integrate A.I.

into learning, Stephanie Sy looks at its growing impact in K-12 education and the warning signs around its use.

STEPHANIE SY: Amna, parents and teachers are still trying to get a handle on students' use of social media, and now they're being forced to grapple with A.I.

too.

A recent survey from the RAND Corporation found more than half of U.S.

students are using A.I.

for school, an increase of 15 percentage points this year compared to just two years ago.

At the same time, 61 percent of parents believe A.I.

will harm students' critical thinking compared to just 22 percent of school district leaders.

All of this as A.I.

juggernaut OpenAI gets even more embedded into the business of American education.

Today, it announced a new partnership with school districts across the country.

The company says it is giving roughly 400,000 K-12 educators free access to a version of ChatGPT through the next academic year.

Let's start by hearing from some parents and teachers grappling with the onset of A.I.

in schools.

L.C.

CARTER, Parent: Hi, my name is L.C.

Carter.

My daughter is in the ninth grade and she's 14 years old.

I use A.I.

every single day.

Of course, I know that they're using A.I.

as well.

But she has expressed that she uses it to mostly just kind of help guide her in her writing assignments to make sure that her argument is present, that it's cogent.

CHRYSTAL JEAN, Teacher: I'm Chrystal Jean, and I'm a teacher.

Being in this profession for as long as I have, change is always there.

And A.I.

is just another change.

It's not going anywhere.

SARAH RIVLIN, Parent: I'm Sarah and I have a child in 12th grade.

The superintendent of Houston Independent School District, where my child goes, is a big fan of A.I., and it's taking the place of teachers' ability to write curriculum and experts' ability to write curriculum.

MATT WALTON, Teacher: I'm Matt Walton.

I am a technology and engineering education teacher in Henrico County, which is located just outside of Richmond, Virginia.

To be honest, I think we're - - as a society in America, we're kind of behind the eight ball a little bit when it comes to artificial intelligence and teaching it to our high school students.

CHRIS HAMATAKE, Parent: My name is Chris Hamatake.

I have three kids in K-12 schools.

I have got a fourth grader, a ninth grader and an 11th grader.

If my kids are going to use A.I., I want them to know the kind of questions to ask to figure out, is this an accurate response from A.I.?

Can I trust this?

And how do I prove that it's accurate or not?

CHRYSTAL JEAN: There have been times when students have tried to pass off an A.I.

generation as their work.

And when it's been flagged and I have tried to have a conversation with the student, rarely have they been able to put thought into their -- into their verbalization.

MATT WALTON: I'm an AP computer science teacher, and there's a unit on artificial intelligence in there.

We do talk about the language models out there, such as ChatGPT and Gemini and Microsoft Copilot.

But I also asked my students to investigate artificial intelligence that goes beyond the classroom walls.

For example, how is the A.I.

going to be used in health care?

L.C.

CARTER: It is going to change our ability to critically think about things.

But it's also the future.

Like, it's here.

It's here to stay.

It's being integrated into every electronic device and software that you can imagine.

So I think that we have to embrace it.

And we just got to be careful because I do think the critical thinking part of it, it is altering our ability to think for ourselves.

CHRYSTAL JEAN: Whooo's Reading is a reading log platform that I have been dabbling with and having the students use.

And the writing prompts are A.I.

generated, where you can keep track of the minutes that you read.

And so it's very personalized.

And then you can lower the reading level.

You can put the grade level of the student, if they're seventh grade, but their reading level is, say, third grade.

SARAH RIVLIN: I have heard a lot of people say, oh, it's an aid to students.

It helps them.

But if you're using A.I.

to help you organize your paper or to help you come up with ideas or to help you strategize for your paper, you're not learning how to do that yourself.

CHRIS HAMATAKE: I don't necessarily have a problem with that being introduced into the classroom setting, as long as teachers are able to take the role of the supervisor, the fact-checker with it.

And that can be hard because we ask a lot of our teachers anyway.

And I don't know if they have the bandwidth for that.

STEPHANIE SY: I'm joined now by Justin Reich, the director of the Teaching Systems Lab at MIT.

He's also the author of "Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can't Transform Education."

Justin, thanks so much for joining us.

You heard the anxiety, the opportunities, the uncertainty associated with this technology.

Your research has really been focusing on this, in particular with K-12 education.

How prevalent is this technology right now in schools?

And what are the disruptions we're seeing from it, for better or worse, at this point?

JUSTIN REICH, Teaching Systems Lab Director, MIT: Well, as you said at the top of your piece, I was co-author on that RAND paper which showed that about half of teachers and about half of students most recently reported using A.I.

and that number continues to grow.

It's much higher in secondary school, middle and high school than it is in elementary school.

The enormous concern that educators have is that, when students are using A.I.

to do their work, they're not thinking, they're not struggling, and they're not learning.

Some of that looks like cheating.

Some of that is a very sort of classic case of a student taking work from somewhere else and representing it as their own.

But in other cases, it's more subtle problems, where students are using machines to produce work and they're not doing the thinking and struggle that they need to do, as many of your guests articulated, in order to be able to learn.

Teachers and students are also excited about the fact that these tools are for sure going to empower human beings to do all kinds of new things.

And so we want to find ways of navigating the opportunities they present also with some real immediate concerns that teachers, in particular, I think, feel quite earnestly.

STEPHANIE SY: Now, and you have OpenAI now freely giving it to thousands of teachers, saying ChatGPT will enable teachers to be better at their jobs.

We spoke to the superintendent, Justin, of a large diverse school district in Virginia who is part of this new initiative.

Here's what she said.

LATANYA MCDADE, Superintendent, Prince William County, Virginia, Public Schools: It's a very diverse system with diverse needs.

What that means is, is heavier demand placed on our teachers, because our educators are the ones that have to differentiate lessons, look at data across multiple content areas for multiple students.

And that can be a heavy tax on time.

So when I think about what's possible with OpenAI, with ChatGPT for teachers, it really can go a long way in helping supplement what our teachers are doing in the classroom every day, removing some of the barriers of time and the burden of time for teachers to do some of the manual, more administrative things that actually ChatGPT for teachers could do for them.

STEPHANIE SY: Justin, that all sounds pretty great.

I mean, you're a former high schoolteacher yourself.

How do you see that balance between the promise that A.I.

will supplement what teachers do, increase their bandwidth, versus replace what they do and maybe even suck up more of their bandwidth?

JUSTIN REICH: There were technologists in the middle of the 20th century that made a very similar argument when they invented a machine called the Scantron machine, which was the first machine that was able to automatically score multiple choice items.

And they made a very similar kind of argument that this is going to save teachers tons of time, that there's going to be all kinds of new assessment possibilities, teachers will be able to focus on the most important things.

And I think most teachers looking back on the Scantron machine would not say, wow, multiple choice items have saved us so much time.

So sometimes, when we aim for efficiency, we don't necessarily get efficiency.

We actually get a system that is targeted at something different.

So I think we should be very cautious about that risk.

There are more contemporary examples too.

Probably the most important thing is, if we are saving teachers time, that only matters if the learning afterwards is actually better.

So,if teachers are using ChatGPT to make new materials, but those new materials don't help students learn as well as the materials that teachers were creating, then if we're saving time, at the cost of learning, that's not an advantage.

STEPHANIE SY: I want to follow up.

Prince William County, where that superintendent we interviewed is from, is one of those school districts that has a high number of disadvantaged students and English as a second language learners.

That brings up one of the chronic problems that A.I.

presumably might solve, which is how to make sure students aren't left behind.

How do you see generative A.I.

's potential for helping or harming equity in American education?

JUSTIN REICH: So, again, the argument that new technologies will disproportionately benefit students furthest from opportunity is now over a century old.

When radio was first introduced, it was argued that, with radio, the underprivileged school would become the privileged one, that elite lectures could be broadcast into the homes of lower-income students.

And radio did not bring equality.

Personal computers did not bring equality.

The Web didn't bring equality.

New technologies typically disproportionately benefit the affluent.

They benefit people with the financial, social, and technical capital to take advantage of new innovations.

So it is certainly admirable to try to use these new technologies to close equity gaps.

But, over and over again, what we see with many generations of new technologies and education systems is that they really more accelerate opportunities for the affluent than they create opportunities for low-income students.

What makes more equitable educational environments are social movements that provide more resources to families, to students, to teachers, to schools, so that they can do a better job and have more resources to educate young people furthest from opportunity.

STEPHANIE SY: Finally, Justin, how much are educators handing over to tech companies when they adopt these technologies?

And what kind of policies should be put in place, as ed tech gains such wide purchase in the American education landscape?

JUSTIN REICH: Well, I think school district leaders should constantly remember that, for organizations like OpenAI, giving away ChatGPT is a customer acquisition strategy.

These companies are trying to build brand affinity and make students customers for life.

And our public school system should be very careful about how we invite any kind of company into what we take as a public good and as a good that students can't refuse.

I think there are some districts that are exploring questions like, should students and families be able to refuse, be able to say, actually, I don't want my students introduced to those tools, and how would they logistically work with that and how would that work?

Probably, the other thing that school districts really need to keep in mind is that this free technology they're getting is venture capital-subsidized technology.

This is like the Uber rides you used to get for $8 across town.

One day, the investors will want their money back.

And when that day comes, we may find that the consumer experience of these tools gets much, much worse, that either they become more expensive or they have more advertisements, more sponsored content, all kinds of things that maybe we really don't want happening inside of our schools.

So school district leaders making these big purchases or these big acceptances of free resources from schools really need to think carefully, not only about the decisions they're making now, but what they may be locking themselves into for the future.

STEPHANIE SY: Just so much to talk about when it comes to this topic, and we will continue to explore a lot of these A.I.

issues down the line.

For now, we will have to leave it there.

Justin Reich, director of the Teaching Systems Lab at MIT, thank you for joining us.

JUSTIN REICH: It's been a great pleasure.

AMNA NAWAZ: And we will continue our look at A.I.

's role in education next week with a report on its use and regulation at the college level.

That's part of our special series Rethinking College next Tuesday.

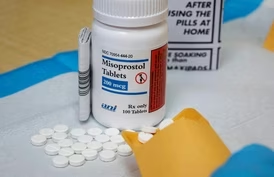

Bans on abortion pills give rise to underground networks

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 9m 21s | Underground networks for abortion pills appear as states limit access (9m 21s)

Comey seeks to have case dropped over handling of indictment

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 6m 21s | Comey seeks to have indictment dismissed over DOJ's handling of case (6m 21s)

Exhibition showcases work of fashion designer Andrew Gn

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 5m 17s | Exhibition showcases pioneering work of fashion designer Andrew Gn (5m 17s)

Poll reveals signs of hope for Democrats, red flags for GOP

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 5m 1s | New poll reveals signs of hope for Democrats and red flags for Republicans (5m 1s)

Trump, MBS unveil ventures on rare minerals and nuclear tech

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/19/2025 | 6m 54s | Trump and MBS unveil U.S.-Saudi ventures on rare earth minerals and nuclear energy (6m 54s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

- News and Public Affairs

Amanpour and Company features conversations with leaders and decision makers.

Support for PBS provided by:

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...