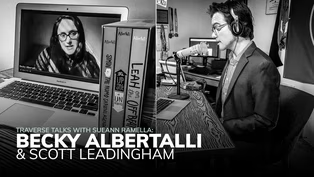

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

Author Becky Albertalli

12/21/2021 | 30m 17sVideo has Closed Captions

On This Special Episode, Author Becky Albertalli On Literature Helping Form Identity.

In this unique episode, NWPB’s former News Manager Scott Leadingham interviews author Becky Albertalli. The two talk about identity, representation of LGBTQIA+ books in grade school libraries, and how people come out and present themselves to the world. Becky is most famous for the Simonverse, a series of young adult fiction novels. Her first book was adapted into the 2018 film, Love, Simon.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is a local public television program presented by NWPB

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

Author Becky Albertalli

12/21/2021 | 30m 17sVideo has Closed Captions

In this unique episode, NWPB’s former News Manager Scott Leadingham interviews author Becky Albertalli. The two talk about identity, representation of LGBTQIA+ books in grade school libraries, and how people come out and present themselves to the world. Becky is most famous for the Simonverse, a series of young adult fiction novels. Her first book was adapted into the 2018 film, Love, Simon.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(dramatic music) - Conversations about identity help us understand each other and ourselves.

My colleague, Scott Ledingham interviewed author, Becky Albertalli who wrote the book that inspired the movie, "Love, Simon," her work deals with identity.

So why are you interested in identity?

- Well, first I'm gonna say this, I'm not someone who people would generally say identifies as romantic or being into romance.

- Mm-hmm.

- You say that you- (laughs) sort of agreed with that a little too quickly, but okay.

(Both laughing) I will say this in my defense, "When Harry Met Sally," is among my favorite movies, and hands down, I think has some of the best writing ever.

I talked about quotable lines.

- Mm-hmm.

"I'll have what she's having."

- (laughs) Exactly.

(laughs) Yes, probably the most quotable line from that movie, but there are many others.

I mean, one of the best movie lines ever.

One of my favorites from Harry toward the end, "I came here tonight not because I'm lonely, but because when you realize you wanna spend the rest of your life with someone, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible."

- Mm-hmm, the New Year's Eve scene.

- Yes, yes.

And other than that movie, I wouldn't say I'm much for romance or even romcom stuff.

- I feel like there's a but coming here, Scott.

(laughs) - Yeah, but a few months ago, I saw this movie "Love, Simon."

- Mm-hmm, that's the one about a teen gay coming out movie romance?

- Yeah.

I mean, pretty standard.

I mean, for 2021 where we are now, it doesn't seem that surprising, but in 2018 when it came out, it was sort of revolutionary in the sense of a big time Hollywood movie taking on this subject in a romcom sense.

And I remember thinking at the time like, "Oh, that's nice.

I'll get around to seeing it sometime, but it probably wasn't gonna be in my normal movie watching genre."

- Why not?

- I think it seemed a little too romcom teeny bopper for my interests.

- Mm-hmm.

- And I'm also someone who has adamantly refused to watch any "Harry Potter" movies or read any of the books.

- (laughs) Oh my god, what?

Why?

- I know, I know it's probably cliche to be a curmudgeon about it, but I just didn't really think those movies and books would speak to me, even when I was younger and they were really big.

Though I watched the movie "Love, Simon," and I really, really liked it.

To be fair, it is certainly not the experience of all LGBTQ teens.

It did speak to me in some ways in my experience, but certainly not all ways.

It's gotten a lot of pushback, I should say, for being a little too sanitized or not really representative of real experiences.

- Okay.

Well, what love story or Hollywood romance is representative?

(laughs) - Yeah, exactly.

Right?

That's sort of the idea, right?

A sappy gay teen romcom love story hadn't really been a major Hollywood project up until that point.

So here comes "Love, Simon."

- Mm-hmm, so you watch the movie, and?

- And then I read the books, "Love, Simon," the movie is based on the book called, "Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda," by Becky Albertalli.

And there's actually a wider set of books called, the "Simonverse," "Simon Universe," that is the basis for the movies and the spinoff things.

There's three books in that original "Simonverse" series, and a new novella came out late last year.

It's based on the actual high school experience of the author, Becky Albertalli.

And there's now even a spinoff series on Hulu called, "Love, Victor."

It's set in the same high school where "Love, Simon" took place.

- Okay.

So it sounds like you liked the books.

- (chuckles) I did, a lot.

And I will say, in ways that surprised me, frankly, kind of shockingly.

- Mm-hmm, but I'm guessing you never considered yourself a fan of young adult fiction.

- Correct.

I did not.

I would say, Stephen King and Jess Walter are my go-to authors, (laughs) and who are quite different than teen, young adult romcom.

- Yes.

(laughs) So why did you read and dive deeply into these books?

What worked well for you with these books?

- See?

That is the question.

I'm not really sure why.

And Sueann, I also have to kind of admit something here.

- What's that?

- Are you familiar with fan fiction?

- Oh my gosh, Scott, like fans of books or movies writing, like when you write additional stuff of characters and post that online, yes.

- Exactly, it's the fans of the body of work contributing to more body of work online and kind of making up their own side stories.

It's a big thing.

It may not surprise you that I have never read any of that, of any kind whatsoever, but it is very big in the "Harry Potter" world, I will say.

- Mm-hmm, and I'm guessing it's big in the "Simonverse," based on Becky Albertalli's books then, yeah?

- Yes, it is very big in the "Simonverse."

And my gosh, (chuckles) there we go, I have been reading a lot of it.

- Why?

- If I knew that Sueann, I would tell you, but I knew (chuckles) I wanted to talk with someone who might be able to shed some light on that.

- Like a therapist?

- (chuckles) Well, I don't have one of those, at least not yet.

(chuckles) But here's the kicker, Becky Albertalli, the author of the "Simonverse" books, started out as a child psychologist before she became an author of these wildly successful books.

- Oh, how interesting.

She has a deeper insight into it.

So you talked to her?

- Yeah, I did.

And it turns out she has a lot to say about identity, and how we come out and present ourselves to the world.

- So here we go, presenting your chat with Becky Albertalli.

(gentle music) - So is it fair to say that most of your audience or the people you hear from are probably young adults, teenagers, early 20s, I'm curious how many people you hear from maybe in sort of late thirties who didn't really realize they were gonna be effected by books that were ostensibly meant for teenagers?

- It's been really interesting.

And I think I try to get a handle on who my audience really is or who I'm hearing from tends to change very quickly.

And I think the pretty big portion of the young adult market are actually adult readers.

And the "Simonverse" skews a little younger, I've found.

Sometimes I'll hear from like 10 or 11 year olds.

I wouldn't say that's like the group I hear from most frequently, but sometimes I hear a lot from teenagers.

I hear a lot from people who are, that are aged.

And sometimes I will hear from like 72 year old gay man, or sometimes I will hear from parents whose kids came out, sometimes parents whose kids came out a long time ago and they wish they'd handled it differently.

It's been really special to have the opportunity to hear from so many different people.

- Looking through the FAQ's on your website, and it struck me that those exist because you actually do get a lot of those questions and it's probably grown over time, but it seemed like I maybe interpreted a little bit that you probably got a lot of feedback from especially young teenagers who encountered Simon and the other books, and then were aware of your background as a child psychologist.

And we're actually asking you for advice, not necessarily from a fan standpoint, as much as a, "I kinda need some help."

And was that hard at all if that you couldn't offer that 'cause you weren't a professional at that point?

- No, it's incredibly hard.

And I think one of the reasons that I became a therapist in the first place, like my previous, my other professional life, was that I feel a strong pull to like try to fix just the circumstances that kids are dealing with.

I find it really, really helpful to have like come into being an author with a whole clinical training, like a doctorate.

And I almost think like, "yeah, you kinda need a doctorate in psychology sometimes to be able to understand kind of the importance of boundaries and how to set boundaries kindly and respectfully, and in a way that is most helpful for your audience and is most helpful for your own mental health.

But it's really, really hard to be a new author and to have a kid reach out to you talking about a tough experience that...

Especially in this space, writing like queer books a lot of times there may or may not be an adult that they can trust, who's safe for them to speak with.

Also sometimes, a lot of the authors writing in this space have had experiences that sometimes mirror the things that teens are coming to them about.

And so it's very tempting to want to be that adult, and it's important to remember that for a public figure, even with a clinical background, (chuckles) like I do, like if you are not a licensed professional engaged in a like specific therapeutic relationship with that person, you do not have the structures in place to support them without eventually failing them, you know?

So I think it's really important to you do choose to engage at all, It should be in a very particular way, and anyone who's a public figure is sort of trying to kind of navigate that, feel free to just like copy paste my website.

I don't run these organizations, but I'm so grateful for them.

- I mentioned to you previously that I had essentially bought the book series, all the "Simonverse" novels, the collector's edition, a three together.

- But say, I love it.

(laughs) - Yeah, and then at the same time, then that's when I also discovered that the "Love, Creekside" novella had come out.

So I was like, "oh, that's awesome."

So I guess that I had essentially bought them to put in my mom's high school library, the same high school that I went through.

And of course there was really nothing like that in the high school when I was going through in the early 2000.

So like I said, I read them multiple times just because I very much connected with the stories and I very much appreciated them, as I've said.

But also just to double and triple check that they were "okay for a high school audience," meaning that not because of what you'd written, but because how people might perceive them.

"Oh, they talk about sexual things.

They say the F-word," cause teens talk like that.

I don't know.

Have you gotten any that sort of feedback or pushback of like, "well, these are for teens, but they're too 'dirty.'"

And how do you respond to?

- Yeah, it presents very inconsistently.

Sometimes, I have that in some.

I haven't gotten as much as some other authors, a lot of that just due to kind of privilege.

And I think I come off as somebody who seems like a "safe point of entry," (chuckles) like I was perceived as being straight and continue I think to be discussed and perceived as straight.

I'm married to a guy, I'm white.

Just all of these layers of privilege that I am shielded from a lot of the pushback that you sometimes see, like I have many friends who are gay men, authors who are gay men and we'll sometimes be told they're not welcome.

And this is not exclusive to gay men.

This is absolutely also true of trans authors, for sure, and also queer women.

We need to cancel this school event, or you can come do the school event but you can't mention that you are queer.

And just a lot of soft censorship, which doesn't necessarily raise the same kind of fuss as like, when we think of censorship in schools.

I think we think of like parents protesting this book and it being removed from the library and a bit like.

And that absolutely happens.

I feel like is the most banned book again and again, it seems like, I'm not sure if this is the number one most banned at the moment, but the book, "George," by Alex Gino, which is a fantastic book and it is a book written for, I would say the target audience is around like 4th or 5th-grade or something.

And that's where people get really sensory.

(chuckles) I guess like, you're not like, you really see it a lot.

I see it less with high school, but a lot more with middle school, I've known so many in middle school librarians who have to work so hard to convince the administration to even allow your middle grade books, which conventionally does not have like cussing or drinking and things like that.

Like that's a younger target audience with young adult books.

Mine, it's a little hazier, like sometimes legitimately certain settings can't deal with f-bomb.

Like, sure.

That's fine.

Sometimes it's almost as if a book has like a certain number of strikes against it, kind of that would kick it out of the library.

And like a queer book gets a strike for being queer and then a strike for the f-bombs and then a strike for whatever other content like drinking or something.

And so therefore if you had two books that were kind of identical in content, but one was a LOC set narrative and one was queer, The queer one would be seen as less appropriate in certain settings.

Obviously, that's not across the board.

And a lot of times I don't think people are aware of it.

There are people in the book community who are like on the ground in the schools and stuff who are like waking up and like going back for these books for their kids, for their students, every day, it's pretty much appreciated, I think.

- That makes me feel good 'cause I might follow the line of better to ask for forgiveness rather than permission, and just put the books in the library without asking anyone's permission, maybe even my library and norms.

- Yeah.

(laughs) (dramatic music) - At nwpb.org, you can find news, music, art, and culture.

Never miss out on the stories from your community by bookmarking nwpb.org.

Nwpb.org, a website that engages, enlightens and entertains.

- You mentioned some terms that maybe not everyone are familiar with, if they're not, even the LGBTQIA+ space.

You said, "cishet," and then you also said you previously identified as cishet, and I would say cis.

And there's some interesting nuance there that I want to get into, but if you could just explain real quickly what those terms are shorthand for and what they mean.

- So cis is kind of a simply, a word that means like, not trans.

So that means you experience your gender as the same as what it was assigned to you at birth.

And if you hear people say allocishet, allo means, not asexual.

Het means, heterosexual.

If you hear somebody use the shorthand cishet or allocishet, that means basically somebody who is heterosexual, like somebody who's straight, not trans, and not asexual.

- And so to the point of you saying you are cis and previously would identify, or people would have identified you and maybe still do as cishet, that's the point I wanted to come to.

You wrote in August of 2020 in a very personal, revealing, and I imagine, pretty tough to write, I don't know, Medium post.

(chuckles) And I gummed onto it and I really appreciate it.

I wanna read a little bit from that.

"But labels sometimes change.

That's what everyone always says, right?

It's okay if you're not out.

It's okay if you're not ready.

It's okay if you don't fully understand your identity yet.

There's no time limit, no age limit, no one right way to be queer."

So what led up to you writing that?

And what were you saying in that?

- So one of the things that's so interesting, but particular about that quote from the essay I wrote, it is absolutely a 100% what I believe that labels can change, that there's not one right way to do it.

It is also kind of messaging that I had heard within my various communities.

But what I think was so hard is that the way the conversations tend to play out in these spaces really undermines the very heart of that message.

That we can kind of hold the idea of yes, like sexuality is fluid.

Gender is fluid.

Like these labels can change.

We don't know everything about other people as well.

And so there may be identity labels that somebody already knows applied to themselves, but they haven't shared that publicly.

And we know all that, but the ways in which we interact with each other online doesn't make space for that, in my experience.

I wrote this piece, I wrote it a while before I shared it, and writing and sharing this essay, I mean, the way I came out to my family was I sent them this essay.

And I did the thing that so many people have had to do before me, had all these really, really awkward conversations with a lot of friends.

And that was all very normal queer experience, in some ways, and certainly on the lucky and privileged side of things.

And it was like, there was a lot of just like, I don't wanna do it, this is gonna be awkward.

The last thing I wanted to do is age 37.

I just don't wanna have this conversation with my parents.

(laughs) I'm just like, "this sounds terrible," but I did it.

And then I posted something on Instagram and then it kind of migrated to Twitter, I knew it would, and was shared pretty widely.

And it was awful.

It was traumatic.

It was absolutely awful.

I haven't talked about it a lot publicly because it's hard to talk about, but by being vague, as I was a bit vague in my essay, people just don't believe you, like I just wasn't believed.

- Like it was performance art or something that you were accused of.

- Yeah.

Oh, I was accused of a lot.

I mean, and I knew this would happen, but I didn't know what else to do because a variation of it had been happening to me for a very long time, which is like, there are definitely people who thought that I was lying.

I heard my bisexuality called, "questionable and suspicious" because there was a kind of suspected, like profit motive.

Like as if maybe kind of I had made as much money as I could make presenting a straight.

So now I'm trying to like kind of tap into the #OwnVoices audience or something, which- - And #OwnVoices is being the movement for people of a certain representative community to be the ones to tell and write their own stories.

- Yes.

- I wonder if you were unintentionally or maybe subconsciously writing these coming out stories in various ways, and even in "The Upside of Unrequited" where Molly, it's a heterosexual attraction.

Molly, the young girl exploring her interest in boys, but still, like the way you present yourself to the world, you've written about that in all of your books, really, right?

And especially the "Simonverse" one's, but was the subtext there, you were trying to figure out how you were going to eventually present yourself to the world.

And maybe you didn't realize you were writing that at the time.

Like all these characters are dealing with a kind of coming out, in some way.

And eventually you came out in a way that was very difficult and you didn't realize you were kinda preparing yourself for that.

- Consciously, had no idea.

Like absolutely not.

There's no part of me that like sat down and was like, let's play out some of these coming out scenarios that I am so anxious about or something.

And I think this tied into some of the backlash because I had in interviews, like when asked, I said, "I was straight and I talked about leading up to this, I worked with queer kids for a very long time.

That was my specialty as a psychologist."

It was not a psychologist for very long.

It was just a community that is very invested in a long time.

That is a classic story like that.

(laughs) It is like a cliche, almost.

It's like the overly invested ally.

Right?

Like you hear about that all the time.

It's hysterically funny, you have the moment where you're like, "oh," to even be aware of the overly invested ally.

I was going around, like people would be like, "so what is your connection to Simon?"

They'd be like, "Simon is probably, I mean, I don't know.

I think all my characters have a lot of me, but like Simon is so much of me, in hand and...." But I would always like, kind of throw shade at him and I'd be like, "yeah, but I'm like Simon, if he had self-awareness."

Well, turns out, (laughs) I'm like, "no, I'm just Simon, like less self-awareness."

A lot of the backlash assumes that kind of the way it works is I wrote these queer books, third, whatever reason, for profit, jumping on some kind of bandwagon, and then there was success, but also backlash.

And then I came out as a way of shielding myself from criticism.

My experience of it is like, I wrote these books, had no idea why.

(chuckles) I also was like, writing queer fan fiction and like doing all these things that like queer people I found out later, very commonly do.

Like it is like so common for people to realize their queer writing fan fiction.

I wrote it too.

Didn't realize I was just a little denser than everybody.

(Both laughing) And then I'm like, huh, okay.

Like I was just like roasting myself.

Where I was just like imagining, like there's this little like exasperated person with a megaphone in my brain who's like trying to make me see it.

And they're like, "okay, okay.

Well, the fan fiction didn't do it.

Let's see.

Let's see."

Maybe let's have her do her in high school.

We're in high school now.

Let's have her do her senior project about like queerness in anime.

Okay.

Okay.

Nope.

She still doesn't get it.

All right.

All right.

Let's have her go to Wesleyan in Connecticut, where everybody there is like queer.

(Both laughing) - That's you.

- Nope.

She's still not there, you know?

All right, grad school, let's have her like, and it's just like, unfortunately for me, my coming out didn't have to be hard, but it ended up being really hard because it had to happen on such a large scale.

- Right, which was maybe unintentionally similar to the theme in Simon.

- Mm-hmm.

- I mean it's like, life imitates art, imitates life, or whatever.

(laughs) - Yeah.

It's just, yeah.

- You were sort of forced.

That's a very tough and sensitive topic, and again, I appreciate you writing that.

(uplifting music) - Do you know a child who's interested in the world around them and how it all works?

Then check out one of NWPB's local productions, "Ask Dr. Universe," a series that answers kids most baffling science questions in a fun and engaging way.

Head on over to askdruniverse.wsu.edu to learn more, or submit a science question of your own.

(uplifting music continues) - I wanted to ask about "Love, Simon," in particular, and "Love, Victor" in terms of their movie presentation or their visual presentation, of course come off in a very romcom esque sort of way, which is we know well that that genre of TV and film, and of course "Love, Simon," I guess, is the closest corollary we have to a young adult, romance-like book.

It's not Danielle Steel novel, (laughs) but what I'm getting at is when I finally got around to watching the movie and then reading your books and talking with and mentioning it, who are similarly in the LGBTQIA field, they say, "they're great.

Loved the movie, loved the books, but they're not really realistic."

That's what I heard a lot.

And I kind of had to push back on that a little bit because I thought, "well, they spoke to me in a lot of ways."

So it was realistic in some ways, for me, not entirely, but it was.

And not just because it's a gay teen, but because I felt like there was a lot in there about how angsty teen's life can be, and how hard it is to navigate the next years of your life not knowing what they're going to be like and being so afraid of the end of high school.

And to me, that seemed very realistic because everyone can identify with that in some way.

Not that everyone's high school experiences are the same, they are certainly not.

So are your books generally meant then to be reflective of experiences or maybe aspirational toward these broader themes that we see in romance novels that yeah, they're not realistic, they're aspirational 'cause they make us feel good.

- Well, I think there are a bunch of different kind of threads that I'm sort of catching on this question.

First, I wanna definitely say I actually do call my books romcoms, either romcom or coming of age.

I think for me, that's just because within publishing, when you label your book a romance, I think within publishing that it has a specific meaning with specific conventions, so I definitely wanna be careful about doing is kind of marketing my books as romances, and then having readers go in with a certain set of expectations and then possibly finding that my books, which were not written those in mind, may like violate those expectations.

Yeah, but I wouldn't call mine necessarily that genre, but it's really interesting kind of putting a book like that out there.

And I think this is true of every book.

I know this is certainly an experience that I share with my friends have kind of had, the similar disorienting experience of having a ton of feedback come in and some of it is directly contradictory, but it was all coming from a very authentic place for that reader.

And it really reminds you how much our own experiences like services filter for what we read.

So you end up with, I would say, a subset of readers have said that like, "yeah, Simon is really fun, but it's definitely unrealistically carefree, kind of everything's just a little too easy for Simon, it's very much aspirational in that way."

And then some people read it, they're like kind of upset to read it and realized whoever recommended to them has been calling it a fluffy romcom.

And maybe they even liked the book, maybe that reader even enjoyed the book, but they considered it traumatic, force outing is a part of it.

And there is some trauma associated with Simon story, and when the film came out and the film is of course different from the book, so you end up having people watching this film who think this is absolutely the mostly ridiculously sanitized, like, "I can't connect to this at all."

Like, this kid has a perfect life.

And you have people who are triggered by Simon being forced out, and Simon's friends, there's some complexity around their reactions to him coming out.

Like it was upsetting for certain people watching it.

And I mean, there are certainly patterns to the different reactions, like generational divides and kind of how people experience the story.

Sometimes it's very moving to see the range of reactions, and just the ways that people's experiences play into it.

They do think a lot of times we as consumers of media can feel a little betrayed if we go into something, expecting it to resonate with our experiences and then it doesn't, and it feels like, wrong.

And so there are definitely people who this is unrealistic or it's like written for straight people, or it's just like, it is unrealistic in a way that I love, because it is subverting in this romcom trope that like the cishets have had a feel with already, so it's just like all these different reactions to.

And then some people who are like, "this is like reading my own diary.

It's so realistic I almost had to like, put it down."

Like yeah, it depends on the reader and the viewer.

- And that was a little bit of my experience.

I'll just say personally, again, it didn't speak to me in every single way by any means, but it was definitely great help in that way.

Just helping me think through some of my own things.

Like I said earlier to you, I didn't come out until a little bit later in college, in grad school, but looking back, I don't think it was because I would not have been supported.

In fact, I very much, I think would have been even at that time, 18 years ago or so.

And your book really put things in perspective, personally, for me, and I imagine many others who thought, "it was my own misgivings.

It was my own unwillingness to have things changed," which was sort of a theme for both Bram and Simon.

And so I appreciated that, and it spoke with me in that way.

So Becky Albertalli, I know we've been talking awhile and you have family obligations to get to.

So I just wanna appreciate everything that you've written so far and our conversation today.

So thanks for joining us.

- Thank you so much for having me.

This is lovely.

(serene music) - "Know thyself," an ancient Greek aphorism.

In modern speak we say, "identity," a self-examination, your measure place, who you are, who you love.

For this "Traverse Talks," you heard my colleague Scott Ledingham interview author, Becky Albertalli.

She wrote "Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens," which became the movie, "Love, Simon."

Thanks so much for listening to "Traverse Talks."

(serene music)

Author Becky Albertalli - Conversation Highlights

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 12/21/2021 | 3m 50s | Conversation highlights between author Becky Albertalli and Scott Leadingham on identity. (3m 50s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is a local public television program presented by NWPB