Beadwork, Filmmaker, Willmar 8

Season 15 Episode 6 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Raine Cloud's beadwork; Karina Kafka's feature film, and the ”Willmar 8” legacy.

Raine Cloud shares her intricate beadwork; Karina Kafka, a young filmmaker from Ortonville, directs her first feature film; also, learn about the ”Willmar 8” the first bank strike in America.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Postcards is a local public television program presented by Pioneer PBS

Production sponsorship is provided by contributions from the voters of Minnesota through a legislative appropriation from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund, Explore Alexandria Tourism, Shalom Hill Farm, West Central...

Beadwork, Filmmaker, Willmar 8

Season 15 Episode 6 | 28m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Raine Cloud shares her intricate beadwork; Karina Kafka, a young filmmaker from Ortonville, directs her first feature film; also, learn about the ”Willmar 8” the first bank strike in America.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Postcards

Postcards is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(bright music) - [Narrator] On this episode of "Postcards."

- But just seeing her out there dancing, and just all this love, it's just like really a good feeling.

All those hours of love.

(gentle music) - I think maybe in middle school is when I decided I wanted to become a filmmaker.

(gentle music) - Other people gave up on us, or failed us.

We never gave up.

(upbeat music) (upbeat music continues) (upbeat music continues) - [Narrator] "Postcards" is made possible by the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

Additional support provided by, Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen, on behalf of Shalom Hill Farms, a retreat and conference center in a prairie setting near Windom, Minnesota.

On the web at shalomhillfarm.org.

Alexandria Minnesota, a year-round destination with hundreds of lakes, trails and attractions for memorable vacations and events.

More information at explorealex.com.

The Lake Region Arts Council's Arts Calendar, an arts and cultural heritage funded digital calendar showcasing upcoming art events and opportunities for artists in West Central Minnesota.

On the web at lrac4calendar.org.

Playing today's new music, plus your favorite hits, 96.7 KRAM, online at 967kram.com.

(gentle music) - When I learned how to do bead work, one thing that some of my teachers always taught was, don't bead if you don't feel good.

'Cause those feelings go into your work, or you're gonna like mess up, or you're gonna be frustrated.

So there'd be times I really wanna bead, but I'm not feeling the feeling yet, so I'll just separate my beads, group and sort them.

And I'm just like sitting there doing that.

And then it just like my feelings feel better, and then I'll be like, "Okay, I'm gonna start on my project."

(gentle music) My first exposure to art was seeing my grandma making star quilts.

Both of my grandmas made star quilts.

My mom's mom, I was always kind of sickly as a kid, so I had to like stay home with her.

She'd gimme this big box of scraps and she showed me how to sew and I'd make these little Barbie blankets and stuff.

And so I was like five, six years old, and I just had like all this valuable time with my kunsi, my grandmother.

And she just taught me a whole lot, just about sitting quietly.

And then my mom, she would make clothing, Pendleton coats.

I remember going to sleep at night, and she would have this Pendleton blanket and I'd wake up in the morning and there'd be like a Pendleton coat hanging up, that she made all night.

So I mean I guess I grew up around that.

Just creativity, just seeing people make things.

(gentle music) And so when I started beading, I had seen my mom make barrettes and stuff, but she wasn't like the bead worker.

She was always sewing, she was a really good seamstress.

I just got this book and it said like "Native American Bead Work."

And I just read how to bead, and I grabbed a barrette that I liked and I just copied it.

And then from there I just kept making things and making things and talking to people like, "Oh, how do you make this?"

Or they would tell me how they made something.

Like with Super, he made moccasins and he's like, "I can show you."

And I was like, "Sure."

And just spending the time to learn.

These older ones wanna pass on that knowledge.

Just being there to collect it and learn and ask questions, I think that's really important.

(traditional music) Powwow outfits, or making our outfits for the powwow.

That was like why I started beading.

Watching my mom make our dresses and making outfits for my brothers.

Just watching her make things, I kinda learned.

The first dress I made, I was like, "I made this!"

And she's like, "Who showed you how?"

And I'm like, "I just watched you like all this time and I learned."

I don't feel like she realized she was teaching me how to make it.

She would just tell me all her little tips and tricks and stuff.

And then when I had my daughter, you just want your kid to look the cutest.

So I'd make her all her little outfits and she's my little doll and I just make all her little stuff.

And I also wanna be confident and know that she looks good and cared for and loved by making all this stuff for her.

And so every year she grows and sometimes it's so disappointing 'cause she just grows so fast and it's like, "I just made that, and you already grew out of it."

So this is like her old stuff.

We made this together.

So this goes with.. See, these are her old moccasins.

I wish I could just find all her little sizes of the same moccasin.

(Raine laughing) So she's kind of outgrown this set.

(gentle music) Just making new stuff for her has kind of been like the past 10 years of what I've been doing mainly, 'cause she's my muse.

Right now, I'm just making this cape for my daughter, for her fancy dance outfit.

Super made her a pair of moccasins, so I just kind of used his moccasin design and colors as the inspiration.

So she has a whole set that matches.

Whatever she wants, we go to the fabric store.

"What do you like?"

We talk about things and make things her favorite colors.

When I see her dance in something that I made, or that me and my mom made together, or all three of us made together, 'cause she works on her own outfits now too.

She sews on fringe and she does stuff.

She helps us too, now that she's older.

But just seeing her out there dancing and just all this love, it's just like really a good feeling.

All those hours of love.

This could take an hour and a half to do this line.

So it's a couple hours here, a couple hours there.

I start in the middle and I work my way out, and then filling in the background.

So I actually did this on the way to Montana, like this whole upper half.

(Raine laughing) So, I don't know, if I just get uninterrupted time, I could work really fast, 'cause I've been beading for so long, it doesn't take me a long time anymore.

And plus I don't have to figure things out 'cause I already made it in my mind.

And now I just like plan it out on paper.

Now this is gonna be the second half, the front half of that.

And then, so I've kinda used the same design.

And we were talking about what to put up here.

So me and my daughter are still talking about this design here.

So, we'll see.

(gentle music) - [Off-Screen Voice] Last one standing.

- [Off-Screen Voice 1] Yes.

- Yeah.

- Are you making new bead work too?

- [Off-Screen Voice 2] I'm gonna make some new earrings.

- Every Friday night, I have this beading keyapi.

So keyapi in our language means, it literally means "They say."

So you'd be like, gossip.

But I just say it just to be funny, 'cause it's like, who doesn't wanna know the gossip?

But it's kinda to get people to come over.

I use conditioner and then I use beeswax on top of it.

But this one, I just use this one.

I wanted to set a couple hours a week to work on bead work.

And I was like, I get so distracted.

Or I'll be like, "Oh, it's fine.

I'll work on it later."

And I'll never get to it, you know?

So like weeks pass and I'll never touch my bead work.

But I'm like, if I set aside a few hours on a Friday night, and then also like go on Facebook and invite everybody, then people will come over.

And so it works kind of like an open house, 'cause people come over for an hour, somebody else will show up and somebody else.

So it's like all night, people are just coming and going.

And it's also cool, 'cause there'll be something I don't know.

And then somebody will come and then they'll show somebody else how to do something.

And then sometimes we just sit around and eat and talk and bead.

So it's like, it's not always teaching.

So it's sometimes you have to know really good gossip.

(Raine laughing) I get all the tea.

(Raine laughing) Oh I was like, "Oh oh."

- Yeah.

Uh oh.

(ladies laughing) - Tukte wanzi yacin he?

So I really used my knowledge of bead work to teach language.

It's the thing I'm most passionate about right now.

I want somebody to make something and learn the words of how to say leather, how to say beads, how to say all these things that you're using.

And then also the technique, but they're also like, "Hey, can you pass me the scissors?

Or I have some string."

And sometimes it's awkward to speak the language because you're so vulnerable and you're scared of making mistakes.

But if you're making something or doing something, and talking, like you don't feel everybody looking at you, 'cause everybody else is doing stuff.

Right now, a lot of things that I make, I don't charge for them, because I don't need the money.

'Cause I work, so I'm like, I would rather get something from them that they made.

So it's kind of like this exchange.

And you never know, one time I got a jar of like antique beads and stuff.

It was really cool.

You never know what you're gonna get if you say you wanna make a trade.

(gentle music) I think about Dakota women, we're always raised to be industrious.

This is our Dakota ways.

That's still important.

A part of like our way of life, because especially nowadays, so many people are on their screens and on their phones.

And we have to keep our young people doing these things and adapting.

We're a living culture, so we're gonna change.

Like this is just how it is.

So it's the "Mandalorian."

(dramatic music) This is like my third "Mandalorian" skirt.

This is just the latest.

(Raine laughing) So it has like the little gold thread.

This is the little details I like.

So I think this is like, the reason why I make things, is because I make things I wanna wear.

You know?

Deced ecunpi.

This is the way.

Yeah, Dakotans are Mandalorians.

It's a fact.

You can record me saying that.

Get me on camera saying that.

- [Crew] Yeah, yeah.

- Language changes.

We change.

Everything's changing.

But I try to preserve the old ways, as much as possible.

So learning those old ways of like brain tanning, learning the old ways of our old designs, the kind of beads that they used in the 1800s.

In the past years, just realizing my Dakota lineages, Bdewakantunwan, I just really start loving the more floral and the woodland designs.

Learning my own history of my lineage changed my art.

(gentle music) That's just like my wall of my favorite people.

So I have my great-great-great grandfather, Taoyateduta, or Little Crow.

Growing up, I just didn't really grasp who he was until I was probably a teenager.

Like his importance in Dakota history.

To me, it was like just somebody in our family.

And then I went to school and I started learning about Minnesota history and I was like, "Wow, he's significant in Minnesota history."

(gentle music) A lot of times people just judge you on the way you look, automatically, or they have a stereotype of what Natives should look like.

"Oh, you speak the language?

You should look like this.

Oh, you do bead work?

You should look like this."

And I don't.

I think growing up amongst a lot of darker Natives and be called White girl and stuff like that, it just really was a source of insecurity for me.

Knowing my history and knowing where I come from, knowing my ancestors, helped me overcome that, and really just know who I am.

I'm not trying to look the part anymore.

There was a part of my life where I felt like I had to have like long dark braids and stuff.

And now I'm like, "I'm just gonna look like me.

I'm just gonna look how I think I wanna look."

(gentle music) A long time ago, Dakota women would gather and make things, or be industrious, especially in the winter time.

That's like when we would make all of our things.

And then at some point in history, we just got to making bead work or trinkets for people was a way to make money.

This was something we did for survival.

Now, I feel like my thought of bead work is kind of like, I wanna make something beautiful for my friends.

I wanna make something beautiful for my daughter.

As somebody who creates things, I like to look at what I made.

Like, "Oh wow, I made that.

Wow, that looks really good on her."

That brings me more joy than any dollar amount could do.

(gentle music) (gentle music continues) - I grew up in Ortonville, Minnesota.

And it's a fairly small town, 1,800 people.

And childhood was pretty good.

I grew up in a predominantly White town.

So it was a little difficult for me growing up.

But as I got older and decided I wanna move to a bigger city with more people of color, it helped a lot once I moved.

And I still love the town.

It has its good qualities.

(gentle music) But I think maybe in middle school is when I decided I wanted to become a filmmaker.

(gentle music) My documentary is called "A Mother's Love."

And it's about missing and murdered Indigenous women.

And it's a topic that I had been thinking about doing for probably two or three years before I started filming.

And it started off when Gabby Petito went missing.

And she got so much coverage.

Which, I mean, people should get coverage if they go missing like that.

But it made me realize that if I were to go missing, a woman of color, or one of my friends, or anyone, would they get the same coverage that she got?

And the answer is "No."

And that made me do more research on women of color going missing.

And then it led me to Indigenous women going missing.

And I never realized that they don't even have a number of how many have gone missing.

It's a really serious situation, and it's not getting talked about.

So yeah, that led me to wanting to cover this topic.

And it's a topic that I wanna keep covering.

- When a Native female is missing, or even a Native man, like, "Oh, they're just the big partiers," and you'll find them in the drunk tank, or they'll be in jail, or we'll find them eventually.

No.

It's like this girl disappeared.

Now if it was a White girl, how would you be thinking about this?

Would that have made a big difference?

- I directed, produced, edited it, shot it.

So I got my hand in all aspects of the documentary.

But I really enjoyed getting to know the subject and building that connection.

And you have to build trust with them and just learning more about her life, her perspectives.

(gentle music) The main thing I want people to take away from "A Mother's Love," is to just be aware about what's going on to Indigenous families, women, and try to be educated more on the topic and don't be afraid to bring it up.

(gentle music) - By late afternoon, I was still texting her, messaging her, and I couldn't get ahold of her.

And I was like, "Something's wrong then."

'Cause by now she would've texted me or messaged me back.

Calling, calling, nothing.

Messaging, nothing.

So I waited.

'Cause I was like, "She'll be back."

'Cause that's her responsibility.

She knows she has to come back.

That's when I really got worried.

And then I went to dialysis and then I called the police after that.

'Cause she didn't show up to dialysis either.

My first mistake was waiting too long that first day.

I should have called that evening.

And I thought, "No, she'll come back.

She's grown.

She knows she has to come back.

I need help."

I gotta go dialysis, I gotta do this.

And she's the one that takes me and gets me ready.

The first thing the detective said to me was, "Oh, are you sure she didn't go back to the reservation?

Maybe she's just partying or something."

No, she's not.

She abandoned us.

She's my caretaker.

And if she was gonna do something like that, that's stupid, she would've got ahold of me and told me, "Hey, I'm gonna head out over here."

So she didn't do that either.

She's just gone.

So I really thought, "Why would you think that?"

Is it because, and I asked him that, "Why?"

He said, "Well, I'm just.." I said, "So you think every Native comes from the reservation?

Some of them don't live on a, have never grown up, like my kids."

So it was dumb.

But I already knew in my heart that my daughter wasn't gonna get a lot of coverage.

You already know that whenever your kid is missing and she's Native, that you're not gonna get a lot of cooperation from the authorities.

They're not gonna do anything that they would do for a White girl.

They're not gonna do that.

They're not.

Everybody else will get more coverage than a Native.

They're thought of less than anything, even less than cattle.

Or not even considered valuable as cattle are.

All these Indigenous people are missing, and a lot of it's Native women that are missing.

'Cause we're not thought of.

When I was growing up and a girl would disappear, or she would go to the city and you never heard from her again, just her family would be worried.

Sometimes they go looking for her or that was it.

But the tribe would never help you.

Police weren't really helpful.

Nobody would really do anything.

Nobody really cared.

I had a older cousin, well, older auntie.

She's cousin to my mom.

Her name was Debbie.

And she was about 18 years old, and we all grew up together.

I was really young whenever she left and she was supposed to go on a trip and come back.

And she never came back.

And nobody heard from her for like two or three years.

My grandma would try to look for her.

Call different places and do this and that.

Couldn't find her.

Once in a while my grandma would also wanna go, try to look for her, and my grandpa, and then find her.

So one day my grandmother and them got a phone call and it was from a hospital here in Sioux Falls.

And she was in critical condition and gonna die.

And they needed somebody to come and pull the plug basically.

And my grandma was shocked.

She's like, "Where has she been?"

We haven't heard from her for almost three years.

And she was back.

And the only way grandma got a call was that they found a number in Debbie's belongings.

The police found it, found her on the streets here, somewhere in Sioux Falls.

What they thought was passed out.

And she wasn't.

She had been assaulted or something.

She had a brain injury or something, brain trauma.

And they got her to the hospital, but she died.

Probably the next day after grandpa and grandma got there.

So grandma always told me that, to be careful when you're a Native girl, because things can happen to you.

She always worried about us when we lived in the city, especially me, 'cause I've always been everywhere.

She didn't know what to make of that.

She always told me to watch myself, 'cause she said bad things will happen to you, or could happen to you.

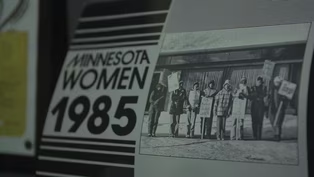

(gentle music) (gentle music continues) (gentle music continues) (bright music) - It was an explosive time.

- Women weren't supposed to speak out like we were.

- Something within them just rebelled.

- And so it was time to take a stand.

(upbeat music) - It was the last straw when they hired another man and wanted us to train him for management position.

We had done this many times in the past and the men would move right up the ladder to management and the women were still down at the bottom, training everybody that came in.

- We felt that we were not being heard.

- And we complained.

- [Interviewer] And what happened?

- We're told we're not all equal.

- We're not all equal, you know?

- We're not all equal, you know?

He said that many times to people.

- We'd be all at the table.

They would turn their back to the table and read newspapers to show that they didn't need to listen to us.

- So we soon found out we were not gonna go anywhere with this.

So that's when we started talking about going on strike.

(bright music) - When I came to first meet with them to ask them if they would be interested in allowing us to do their story, there was some reservation, I'm sure.

- We couldn't believe that they were gonna do this, that it was gonna be anything.

But then Mary Beth Yarrow, and she was from Willmar, so she knew the town, the city, she grew up here.

(bright music) - Documentary is documenting.

All you can do is hold up a camera.

If the situation is interesting and alive, you got something.

- [Interviewer 1] What is your opinion of the women's strike at Citizens National?

- Are you taking my picture?

- [Interviewer 1] Yeah.

- [Bank Staff] When we started with the strike, there was a real sense of excitement.

- We did not think it was going to last long.

- And 10 days and two weeks went by.

We thought they'd have to talk to us.

- But that didn't happen.

The strike continued then for a couple years.

- It got pretty tight.

We weren't getting much money.

- [Interviewer 1] What's the one that's out of your budget right at this point?

- Anything over 23 cents a can, but...

I was looking at the vegetable beef, and that was a little bit more.

(gentle music) - Their quiet kind of bravery.

And this kind of comradery they had was the most important element of this.

(gentle music) - [Bank Staff] We became our own family, in a sense.

- That's what kept us together all that time.

And it of course, we got closer and closer.

- So we don't get together all the time, or see each other all the time, but you feel it once we're back.

- Yep, yep.

- Other people gave up on us, or failed us.

We never gave up.

(gentle music) (audience applauding) - It became a political issue, a social issue, a union issue, and a women's issue, all bundled up into one package.

And we were the package, the eight of us.

- You know what I'd like to do, honey?

I know you're thinking of a question to ask me.

But I would like to read the names.

These are the women of the Willmar Eight.

Doris Boshart, Irene Wallin, Sandi Tremel, Teren Novotny, Sylvia Erickson Koll, Jane Groothius, Shirley Solyntjes, Glennis Terwisscha.

These are the heroines, heroes or heroines, whichever.

(dramatic music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music continues) - [Narrator] "Postcards" is made possible by the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

Additional support provided by, Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies.

Mark and Margaret Yackel-Juleen, on behalf of Shalom Hill Farms, a retreat and conference center in a prairie setting near Windom, Minnesota.

On the web at shalomhillfarm.org.

Alexandria, Minnesota, a year-round destination with hundreds of lakes, trails, and attractions for memorable vacations and events.

More information at explorealex.com.

The Lake Region Arts Council's Arts Calendar, an arts and cultural heritage funded digital calendar showcasing upcoming art events and opportunities for artists in West Central Minnesota.

On the web at lrac4calendar.org.

Playing today's new music, plus your favorite hits, 96.7 KRAM, online at 967kram.com.

(bright music)

Beadwork, Filmmaker, Willmar 8

Preview: S15 Ep6 | 40s | Raine Cloud's beadwork; Karina Kafka's feature film, and the ”Willmar 8” legacy. (40s)

Eight Women Together Alone Teaser

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S15 Ep6 | 6m 11s | The influential women of the Willmar 8 who participated in America's first bank strike. (6m 11s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S15 Ep6 | 10m 2s | Karina Kafka created a film called “A Mother’s Love" about missing indigenous women. (10m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S15 Ep6 | 13m 32s | Raine Cloud has spent most of her life studying and creating beadwork. (13m 32s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by: